Fredric Brown

Fredric Brown A partnered pair of science fictional Forteans.

Fredric Brown was born 29 October 1906 in Cincinnati. He graduated from Hanover College in Indiana, and settled for a long time in Milwaukee, where he worked in the printing trade, also doing proofreading. He married a woman named Helen Ruth in 1929, and they started a family, Helen giving birth to a two boys. Apparently, Brown had only known Helen through correspondence before they married. The Depression was hard on the Brown’s, and Fredric eked by, while also turning out short mysteries, that he began to sell to magazines in the 1930s. He once hoboed to Los Angeles trying to drum up work, and did turns as a detective and dish washer.

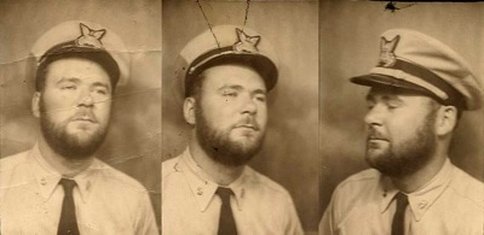

He sold his first short story in 1937, and there followed a mess of tales, their fates difficult to follow. But by the early 1940s, he had hit a groove. Brown was part of Allied Authors, a competitor of the Milwaukee Fictioneers, the later of which included Ray Palmer, Stanley Weinbaum, Roger Herman Shoar (who wrote under the name Ralph Milne Farley), and Robert Bloch, among others. As Bloch remembered Brown from the early 1940s, he was small and fine-boned, with a neat mustache. His apartment had a Siamese cat named Ming Tah, a wooden recorder that he played, a chess set, and a typewriter. Brown enjoyed his alcohol quite a bit.

Beginning in 1943, according to his biographer, “Brown’s short story output from this point on is more manageable, as he began to rework several themes that reveal interesting facets of his concerns.” In addition to mysteries, Brown wrote science fiction, fantasies, and hybrids of the various genres. He was known for his word play and trick endings, and much admired for his craftsmanship. Ideas could be difficult, though, and Bloch remembers Brown hopping on buses and riding across the country when he was was blocked, looking for inspiration. He became an innovator by being contrarian and focusing on the small bore: rather than penning grand space operas, he looked at the problems of science, the failures of rocketry.

Fredric Brown was born 29 October 1906 in Cincinnati. He graduated from Hanover College in Indiana, and settled for a long time in Milwaukee, where he worked in the printing trade, also doing proofreading. He married a woman named Helen Ruth in 1929, and they started a family, Helen giving birth to a two boys. Apparently, Brown had only known Helen through correspondence before they married. The Depression was hard on the Brown’s, and Fredric eked by, while also turning out short mysteries, that he began to sell to magazines in the 1930s. He once hoboed to Los Angeles trying to drum up work, and did turns as a detective and dish washer.

He sold his first short story in 1937, and there followed a mess of tales, their fates difficult to follow. But by the early 1940s, he had hit a groove. Brown was part of Allied Authors, a competitor of the Milwaukee Fictioneers, the later of which included Ray Palmer, Stanley Weinbaum, Roger Herman Shoar (who wrote under the name Ralph Milne Farley), and Robert Bloch, among others. As Bloch remembered Brown from the early 1940s, he was small and fine-boned, with a neat mustache. His apartment had a Siamese cat named Ming Tah, a wooden recorder that he played, a chess set, and a typewriter. Brown enjoyed his alcohol quite a bit.

Beginning in 1943, according to his biographer, “Brown’s short story output from this point on is more manageable, as he began to rework several themes that reveal interesting facets of his concerns.” In addition to mysteries, Brown wrote science fiction, fantasies, and hybrids of the various genres. He was known for his word play and trick endings, and much admired for his craftsmanship. Ideas could be difficult, though, and Bloch remembers Brown hopping on buses and riding across the country when he was was blocked, looking for inspiration. He became an innovator by being contrarian and focusing on the small bore: rather than penning grand space operas, he looked at the problems of science, the failures of rocketry.

Mack Reynolds

Mack Reynolds Brown, fairly financially stable in the immediate post-War years, left his family in 1947, moving first across the hall in their apartment building—which must have been incredibly awkward. In 1948, he remarried, Elizabeth Charlier. That year he also published his first book, “The Fabulous Clipjoint,” which won the Edgar award for outstanding mystery novel. It featured an uncle and nephew team, Am and Ed Hunter, who showed up in subsequent books and a few short stories. Brown continued publishing novels in different genres through the 1950s and reselling his short stories on the paper back market (a way of consolidating earlier gains practiced by a number of pulp fictioneers). He also found a new market in the burgeoning men’s magazines, as well as their more sophisticated competitor “Playboy.”

Fredric and Elizabeth moved a bit, especially wandering around New Mexico, which had an artist colony in Taos. By the 1960s, Brown was in very poor health, and essentially stopped writing—there were a few small projects, and larger abortive attempts. He was mostly forgotten during that decade and the next one, until there was a small revival in the 1980s that grew through the rest of the century, though Brown is still not as well remembered widely as he is among writers.

Fredric Brown died 11 March 1972 in Tucson, Arizona. He was 65.

*************

Dallas McCord Reynolds—better known as Mack—was born 11 November 1917in California, but his family relocated to Baltimore the next year, his father, Verne (supposedly named in honor of Jules Verne), an organizer in the Socialist Labor Party. Mack was raised as a socialist and toured the country giving speeches from an early age. After high school, he became a journalist. Reynolds married in 1937, and he and his wife Evelyn had three children. In 1940, they were in San Pedro, California, with Reynolds working in the shipyards and campaigning for SLP presidential nominee John Aiken. He joined the Army Transportation corps in 1944, stationed in the Philippines.

After the war, his marriage dissolved—Evelyn had cheated on him—and she and the children left. Reynolds remarried in 1947, Helen Jeanette Wooley, a political radical. They settled in Taos while Reynolds tried to break into the fiction magazine market. It was there he met Brown, who encouraged him to expand out of mysteries and into science fiction, too. Reynolds hit his stride in the 1950s, selling hundreds of stories, making a name for himself in the men’s adventure magazines, science fiction magazines, and mystery magazines—under various pseudonyms—selling novels and non-fiction, while also traveling the world: they had been inspired by Garry Davis, citizen of the world (and Fortean) whom they met at a science fiction convention in 1952. In the late 1950s, he broke with the SLP, which accused him of apostasy.

Reynolds and his wife settled in Mexico in the 1960s, and continued to crank out stories at a prodigious rate. But while he continued to write in the 1970s, he had trouble finding a market. He put out a couple of romance novels to make ends meet. He updated Edward Bellamy’s socialist classic “Looking Backward.” There was something of a revival of interest in Reynolds in the 1980s—as was the case with Brown, though I don’t think that Reynold’s reputation aged as well.

Mack Reynolds died 30 January 1983, also aged 65.

*************

Fredric Brown likely discovered Charles Fort with the publication of the omnibus edition of Fort’s work in 1941, according to his biographer—for shortly after that book came out in April 1941, Brown started putting out fiction that incorporated Fortean themes. These became increasingly prominent. It seems that Brown’s cynicism about science made him ready to accept Fort, and then incorporate oddments of the Fortean fantasy into his own philosophy, at least as it was expressed in his fiction. “Perhaps the most important theme,” in Brown’s work, says his biographer, “is that of the influence of philosopher Charles Fort.”

“The Angelic Angleworm” was written in September 1941 (and published in February 1943’s “Unknown Worlds”) had a Fortean flavor. It tells of a series of Fortean anomalies that are resolved by a printer figuring out that the author of the universe is regularly misprinting a bit of reality. There, then, was the Fortean strangeness, but also a higher unity—a nod to Fortean monism. “The Spherical Ghoul,” written in April 1942 and published in “Thrilling Mystery” January 1943 was a locked room mystery with a Fortean twist. Indeed, other authors of locked room mysteries—such as Anthony Boucher—found Fort helpful in providing new ways to solve story problems. “Armageddon,” which was published in John W. Campbell’s “Unknown” featured a recurrent them in Brown’s fiction, people ignoring anomalies. It’s appearance in August 1941 makes it just possible that brown could have read Fort and applied what he learned to the story—but it also may be a bridge, Brown’s ideas prefiguring his awareness of Fort, making him amenable to Fortean ideas.

Brown and Reynolds met in Taos. This was in 1949. One can imagine they had a personal connection, both having gone through upheavals in their married life recently. And Brown was already plying the trade that Reynolds wanted to break into. (They both also knew another pulp fictioneer, Walt Sheldon, who was another mentor for Reynolds.) Reynolds and Brown would collaborate on a number of short stories, and co-edit an anthology, “Science-Fiction Carnival,” in 1953. “Carnival” was published by Shasta—helmed by a Fortean—and included Brown’s Fortean “Paradox Lost” among the 14 stories collected in the book. Which is one way of saying that Brown very well may have introduced Reynolds to Fort, if Reynolds had not already come across the Bronx philosopher, or likely deepened his appreciation for Fort if he had. (Reynolds was reading science fiction before he was writing it, so almost certainly came across references to Fort. The question is, Did he follow up on them?)

Reynolds used Fort in some of his fiction; he was never as died-in-the-wool a Fortean as Brown, but neither can his references be completely dismissed, since they persisted. His 1950 story “The Discord Makers” bore the imprint of both Brown and Fort. It is about an alien invasion, taken by animals—and the proof of their alien status is that these animals (snakes, spiders) innately repulse humans. The story is a collection of Fortean anomalies tied together by the theory of alien invasion—which presaged Brown’s 1962 story, “Puppet Show,” that had a similar twist.

A couple of Reynolds’s novels also mentioned Fort, separated though they were by a decade-and-a-half. “Of Godlike Power,” put out in 1966—though only his second novel—mentioned Fort approvingly. His first novel, 1951’s “The Case of the Little Green Men” was a mixing of science fiction and mystery—more accurately, the setting of a mystery at a science fiction convention. (As Anthony Boucher set a mystery among southern California science fiction writers.) In the course of the story, Reynolds had occasion to use a number of people from real life, including Fort:

“He came back with a heavy book and handed it to me. I looked at the title: The Books of Charles Fort. “What's this?" I asked him. "Isn't Fort the screwball that tells all about the rains of frogs and that sort of crap?”

"That's hardly a proper description of Charles Fort," he said stiffly . . . ”Fort has gathered material for decades in an attempt to show that modern science is too smug, too hypocritical – and too ignorant. He made a hobby, a lifetime work, of gathering evidence of phenomena that modern science has as yet been unable to explain.”

Brown, on the contrary, used Fort profligately, a number of his stories with Fortean inflections of varying degrees. People ignoring anomalies recurred in 1943’s “Hat Trick” and “Paradox Lost.” “Pi in the Sky,” from 1945, imagined the rearranging of stars in heaven to advertise soap—a trick of the Fortean cosmology that also suggested itself to Fortean Kathleen Ludwick. The same year he published a short story called “Compliments of a Fiend,” about a possible werewolf that would later be reworked into “The Bloody Moonlight,” feature Am and Ed Hunter. “The Fabulous Clipjoint” from 1947 had some Fortean musings. At one point, Am says to his nephew, “Look, kid, don’t try to label things. Words fool you. You call a guy a printer or a lush or a pansy or a truck driver and you think you’ve pasted a label on him. People are complicated; you _can’t_ label them. . . That looks like something down there, doesn’t it? Solid stuff, each chunk of it separate from the next one and air in between them. It isn’t. It’s just a mess of atoms whirling around and the atoms are just made up of electric charges, electrons, whirling around too, and there’s space between them like there’s space between the stars. It’s a big mess of almost nothing, that’s all. And there’s no sharp line where the air stops and a building begins; you just think there is. The atoms get a little less far apart. And besides whirling, they vibrate back and forth, too. You think you hear noise, but it’s just those awful-far-apart atoms wiggling a little faster.”

“What Mad Universe” (1949), which featured a character based on Fortean science fiction fan Walter Dunkelberger, had “a philosophy behind it,” his biographer said, that was “almost Fortean: everything is true somewhere, so no anomaly can be dismissed.” His 1950 novel, “Compliments of a Fiend”—unrelated to the earlier short story by the title, though featuring the Hunters, was explicitly Fortean—so much so that Thayer noted it in Doubt as an example of Fortean literature. In the story, Am Hunter goes missing—and Fort provides the clue to what is going on, for Am is short for Ambrose, and there is talk an Ambrose collector might be on the loose. That’s not it, the real mystery rooted in everyday ill-doings, but the solution is reached because of a name inscribed in a copy of Fort’s “Book of the Damned.” “Madball,” for 1953, includes a Fortean anomaly—a crystal ball that really works—and his last novel, the unfinished “Brother Monster,” written around 1965, includes an extended discussion of Fort.

Brown, says Jack Seabrook, was not sure that reality existed—and Fort was key to his solving the dilemma. Reality, Brown came to suggest in his writing, was imagined—written by an author, as in “The Angelic Angleworm.” We lived in a Fortean fantasy, where many things were possible—even as science, in his books, failed to fulfill its promises, the rockets remained grounded, the world not as amenable to our own imaginations as we hoped.

Fredric and Elizabeth moved a bit, especially wandering around New Mexico, which had an artist colony in Taos. By the 1960s, Brown was in very poor health, and essentially stopped writing—there were a few small projects, and larger abortive attempts. He was mostly forgotten during that decade and the next one, until there was a small revival in the 1980s that grew through the rest of the century, though Brown is still not as well remembered widely as he is among writers.

Fredric Brown died 11 March 1972 in Tucson, Arizona. He was 65.

*************

Dallas McCord Reynolds—better known as Mack—was born 11 November 1917in California, but his family relocated to Baltimore the next year, his father, Verne (supposedly named in honor of Jules Verne), an organizer in the Socialist Labor Party. Mack was raised as a socialist and toured the country giving speeches from an early age. After high school, he became a journalist. Reynolds married in 1937, and he and his wife Evelyn had three children. In 1940, they were in San Pedro, California, with Reynolds working in the shipyards and campaigning for SLP presidential nominee John Aiken. He joined the Army Transportation corps in 1944, stationed in the Philippines.

After the war, his marriage dissolved—Evelyn had cheated on him—and she and the children left. Reynolds remarried in 1947, Helen Jeanette Wooley, a political radical. They settled in Taos while Reynolds tried to break into the fiction magazine market. It was there he met Brown, who encouraged him to expand out of mysteries and into science fiction, too. Reynolds hit his stride in the 1950s, selling hundreds of stories, making a name for himself in the men’s adventure magazines, science fiction magazines, and mystery magazines—under various pseudonyms—selling novels and non-fiction, while also traveling the world: they had been inspired by Garry Davis, citizen of the world (and Fortean) whom they met at a science fiction convention in 1952. In the late 1950s, he broke with the SLP, which accused him of apostasy.

Reynolds and his wife settled in Mexico in the 1960s, and continued to crank out stories at a prodigious rate. But while he continued to write in the 1970s, he had trouble finding a market. He put out a couple of romance novels to make ends meet. He updated Edward Bellamy’s socialist classic “Looking Backward.” There was something of a revival of interest in Reynolds in the 1980s—as was the case with Brown, though I don’t think that Reynold’s reputation aged as well.

Mack Reynolds died 30 January 1983, also aged 65.

*************

Fredric Brown likely discovered Charles Fort with the publication of the omnibus edition of Fort’s work in 1941, according to his biographer—for shortly after that book came out in April 1941, Brown started putting out fiction that incorporated Fortean themes. These became increasingly prominent. It seems that Brown’s cynicism about science made him ready to accept Fort, and then incorporate oddments of the Fortean fantasy into his own philosophy, at least as it was expressed in his fiction. “Perhaps the most important theme,” in Brown’s work, says his biographer, “is that of the influence of philosopher Charles Fort.”

“The Angelic Angleworm” was written in September 1941 (and published in February 1943’s “Unknown Worlds”) had a Fortean flavor. It tells of a series of Fortean anomalies that are resolved by a printer figuring out that the author of the universe is regularly misprinting a bit of reality. There, then, was the Fortean strangeness, but also a higher unity—a nod to Fortean monism. “The Spherical Ghoul,” written in April 1942 and published in “Thrilling Mystery” January 1943 was a locked room mystery with a Fortean twist. Indeed, other authors of locked room mysteries—such as Anthony Boucher—found Fort helpful in providing new ways to solve story problems. “Armageddon,” which was published in John W. Campbell’s “Unknown” featured a recurrent them in Brown’s fiction, people ignoring anomalies. It’s appearance in August 1941 makes it just possible that brown could have read Fort and applied what he learned to the story—but it also may be a bridge, Brown’s ideas prefiguring his awareness of Fort, making him amenable to Fortean ideas.

Brown and Reynolds met in Taos. This was in 1949. One can imagine they had a personal connection, both having gone through upheavals in their married life recently. And Brown was already plying the trade that Reynolds wanted to break into. (They both also knew another pulp fictioneer, Walt Sheldon, who was another mentor for Reynolds.) Reynolds and Brown would collaborate on a number of short stories, and co-edit an anthology, “Science-Fiction Carnival,” in 1953. “Carnival” was published by Shasta—helmed by a Fortean—and included Brown’s Fortean “Paradox Lost” among the 14 stories collected in the book. Which is one way of saying that Brown very well may have introduced Reynolds to Fort, if Reynolds had not already come across the Bronx philosopher, or likely deepened his appreciation for Fort if he had. (Reynolds was reading science fiction before he was writing it, so almost certainly came across references to Fort. The question is, Did he follow up on them?)

Reynolds used Fort in some of his fiction; he was never as died-in-the-wool a Fortean as Brown, but neither can his references be completely dismissed, since they persisted. His 1950 story “The Discord Makers” bore the imprint of both Brown and Fort. It is about an alien invasion, taken by animals—and the proof of their alien status is that these animals (snakes, spiders) innately repulse humans. The story is a collection of Fortean anomalies tied together by the theory of alien invasion—which presaged Brown’s 1962 story, “Puppet Show,” that had a similar twist.

A couple of Reynolds’s novels also mentioned Fort, separated though they were by a decade-and-a-half. “Of Godlike Power,” put out in 1966—though only his second novel—mentioned Fort approvingly. His first novel, 1951’s “The Case of the Little Green Men” was a mixing of science fiction and mystery—more accurately, the setting of a mystery at a science fiction convention. (As Anthony Boucher set a mystery among southern California science fiction writers.) In the course of the story, Reynolds had occasion to use a number of people from real life, including Fort:

“He came back with a heavy book and handed it to me. I looked at the title: The Books of Charles Fort. “What's this?" I asked him. "Isn't Fort the screwball that tells all about the rains of frogs and that sort of crap?”

"That's hardly a proper description of Charles Fort," he said stiffly . . . ”Fort has gathered material for decades in an attempt to show that modern science is too smug, too hypocritical – and too ignorant. He made a hobby, a lifetime work, of gathering evidence of phenomena that modern science has as yet been unable to explain.”

Brown, on the contrary, used Fort profligately, a number of his stories with Fortean inflections of varying degrees. People ignoring anomalies recurred in 1943’s “Hat Trick” and “Paradox Lost.” “Pi in the Sky,” from 1945, imagined the rearranging of stars in heaven to advertise soap—a trick of the Fortean cosmology that also suggested itself to Fortean Kathleen Ludwick. The same year he published a short story called “Compliments of a Fiend,” about a possible werewolf that would later be reworked into “The Bloody Moonlight,” feature Am and Ed Hunter. “The Fabulous Clipjoint” from 1947 had some Fortean musings. At one point, Am says to his nephew, “Look, kid, don’t try to label things. Words fool you. You call a guy a printer or a lush or a pansy or a truck driver and you think you’ve pasted a label on him. People are complicated; you _can’t_ label them. . . That looks like something down there, doesn’t it? Solid stuff, each chunk of it separate from the next one and air in between them. It isn’t. It’s just a mess of atoms whirling around and the atoms are just made up of electric charges, electrons, whirling around too, and there’s space between them like there’s space between the stars. It’s a big mess of almost nothing, that’s all. And there’s no sharp line where the air stops and a building begins; you just think there is. The atoms get a little less far apart. And besides whirling, they vibrate back and forth, too. You think you hear noise, but it’s just those awful-far-apart atoms wiggling a little faster.”

“What Mad Universe” (1949), which featured a character based on Fortean science fiction fan Walter Dunkelberger, had “a philosophy behind it,” his biographer said, that was “almost Fortean: everything is true somewhere, so no anomaly can be dismissed.” His 1950 novel, “Compliments of a Fiend”—unrelated to the earlier short story by the title, though featuring the Hunters, was explicitly Fortean—so much so that Thayer noted it in Doubt as an example of Fortean literature. In the story, Am Hunter goes missing—and Fort provides the clue to what is going on, for Am is short for Ambrose, and there is talk an Ambrose collector might be on the loose. That’s not it, the real mystery rooted in everyday ill-doings, but the solution is reached because of a name inscribed in a copy of Fort’s “Book of the Damned.” “Madball,” for 1953, includes a Fortean anomaly—a crystal ball that really works—and his last novel, the unfinished “Brother Monster,” written around 1965, includes an extended discussion of Fort.

Brown, says Jack Seabrook, was not sure that reality existed—and Fort was key to his solving the dilemma. Reality, Brown came to suggest in his writing, was imagined—written by an author, as in “The Angelic Angleworm.” We lived in a Fortean fantasy, where many things were possible—even as science, in his books, failed to fulfill its promises, the rockets remained grounded, the world not as amenable to our own imaginations as we hoped.