Francoise Delisle was born Francoise Lafitte in Maubeuge, France, near the Belgian border, in 1886. Her family was middle-class prosperous, with artistic inclinations, though in time her father lost the family fortune. Restless and Romantic, committed to progressive causes, she left her newly-impoverished family for London, to teach French. She became involved with women’s rights groups and socialism—though her animating cause was pacifism—and through this activity met John Collier, an American syndicalist (with a wife back in the States.) She became pregnant, and also disillusioned with Collier, leaving him to raise her son by herself. She thought Collier too demanding a lover.

At one point during the War, Francoise decided that her pacifist principles compelled her to see military action up-close, and she returned to the family home, where she served as a nurse. Unlike most of the others attending the sick, the wounded, the dying, she did not refuse aiding Germans, and soon enough found her patients almost entirely German. The patients considered herself an angel—which she took as a rebuke, still virginal after two affairs and two children. Eventually, she found herself back in London, scrounging with the aid of her servant, trying to provide for her two sons, Francois, only about four, Paul, two. Because of her marriage, she was considered a Russian alien, which added to her difficulties. Serge harassed her, attempted to attract her back, and then ran back to Russia—where he was still officially married to another woman—and sent her wooing letters, proclaiming his place in the military—which only further turned off Francoise Cyon—the last name she continued to use—her pacifism further fixed by the horrors she had seen on the continent.

One job had come to her from a woman named Edith Ellis. She wanted Francoise to translate a book she had compiled of the writings of James Hinton, Edward Carpenter, and Friedrich Nietzsche. Francis didn’t think such a book would have much of an audience, though the thinkers themselves were interesting: Hinton was a surgeon and advocate of polygamy; Carpenter was a philosopher, homosexual advocate—and had a Fortean connection, having mentored the medium Eileen Garrett late in life. Nietzsche was already well-known in France by that time. Nonetheless, Ellis promised a relatively big payment, and Francoise set about the work. They exchanged some letters—and then it ended abruptly. In September 1916, Ellis died of a diabetic coma. Francoise, not quite knowing what else to do, and living in extreme poverty, wrote to Ellis’s husband, wondering if she could still get her commission.

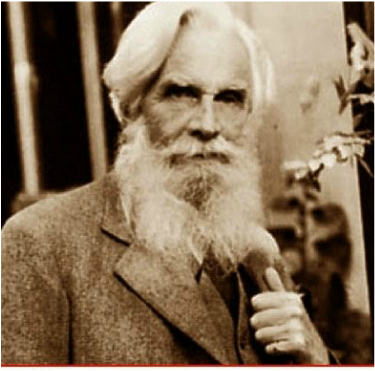

The correspondence changed Francoise’s life, opening up a whole new world, one a complicated as her own, as filled with a revolutionary ferment and chafing against the restraints of Victorianism, rushing toward a self-declared modernity. Edith was married to Havelock Ellis; both supported socialism, women’s rights, and breaking down the stigma around sexuality of all kinds, including homosexuality. He also did seminal work on transgender people—which would be the foundation of work by later Fortean Harry Benjamin (a good friend of Tiffany Thayer). Havelock Ellis was by this point famous for his writing, Edith less so, though she was the more sexually experienced of the two. Edith was a homosexual (an “invert,” in Havelock’s language), and had gone through a series of lovers; Havelock was none of those, their marriage one of companionship and support, though they kept separate accounts and even separate households. By some reports, Havelock had been impotent all or most of his life, though he had shared intimate moments with, among others, the American birth control advocate Margaret Sanger.

Havelock sadly reported to Francoise that Edith’s enthusiasms often outreached her means, and he himself was quite poor, though he offered her a little bit of money. Their correspondence continued, Francoise confessing her many troubles to Havelock. He was kind and empathetic. His writings and philosophy were in line with her own. She fell in love with him, admitting her feelings in 1918. At first, Ellis played coy—he had many women friends, but no lovers: only the purest flower of love. But Francoise won him over, and moved in with him; by this point, her servant had passed, and, I believe, her sons were in France, with her extended family. Ellis and Francoise explored each others’s bodies and discovered new sexual vistas—Ellis overcoming his impotence, Francoise learning to connect her emotions with the physical experience of sex. The two never married—indeed, she was never divorced from Cyon—but Francoise adopted the last of her names to show the attachment. She became Francoise Delisle, a play on the French D’Ellis—“of Ellis—and also easily pronounceable by English and American mouths.

The early period with Ellis was marked by poverty, though not to the depth it had been. The situation improved when Margaret Sanger paid Delisle to be Ellis’s secretary, giving them a consistent lifestyle. When he was thirteen, Delisle’s eldest son, Francois, came to live with her and Havelock. (I am not sure if Paul came too.) It was a short stay, but one that was important to Francois: he thought of Havelock as his adopted father, and he had the run of the extensive and radical library. Although Ellis’s writings posited a time when jealousy would be irrelevant, his own relationship with Delisle was tested severely at the end of the 1920s, when she had a torrid affair with the novelist Hugh de Selincourt. Hugh was a friend of Ellis, and also had slept with Margaret Sanger earlier. Ellis was worried that Delisle had found a younger, more virile lover and would turn her back on him. She plead with him, though, and broke the relationship with Hugh, devoting herself to Ellis and his writing, including translating them into French. The affair ended in 1931.

There is no doubt the there was an intense connection between Delisle and Ellis. They shared a philosophy that was both scientific and mystical—indeed, later researchers have pointed out that Ellis’s science was not always good, but was important socially nonetheless, clearing a space for a considered evaluation of formally taboo subjects. For Ellis, science and mysticism underlay an aesthetic revolution: art was not just important, but a way of life. Starting from very different beginnings, then, Ellis—and, presumably Delisle—had worked himself to the same point as many modernist poets and artists, see art as a revolution against Victorian norms. According to Delisle, Ellis was intrigued by mystical sciences—ESP and associated psychological “wild talents,” in Fort’s potent phrase, but didn’t have time for full consideration; Delisle also was drawn to such phenomena, fascinated by unexplained mental powers.

Some of this affection for alternative forms of knowledge came to the fore in the 1930s, when Ellis became convinced that he had esophageal cancer. He refused X-rays, though Delisle pestered him to get one. Eventually, she convinced him to use Dr. Abrams’ Reflexophone. The Dr. Abrams in consideration, of course, was the San Francisco physician who had invented a novel—most would say quackish—method of diagnosing all sorts of diseases. Mencken had dismissed Abrams, but he had won converts of the early Forteans John Cowper Powys and Theodore Dreiser, and been investigated—and debunked—by a group that included Fortean Maynard Shapley. According to the reflexophone, the growth was not malignant.

And Ellis did struggle on. Born in 1859—about 27 years Delisle’s senior—Ellis was in poor health in the 1930s. Among the causes he advocated was voluntary euthanasia, but it had gained the social traction of others of his enthusiasms. He was in bad shape. Meanwhile, his adopted son, Francois, attended Oxford and became associated with the Communist Party—he would continue his mother’s progressive advocacy and follow in Ellis’s steps. After some clandestine work with the CP, Francois cut his ties and became associated with the Eugenics Society and the associated (but independent) Political and Economic Planning organization—a kind of New Dealish, RAND organization for Great Britain that taught Laffite how to do social research and do political planning. Francois Laffite had gotten the job through the aegis of Ellis, who had been associated with the Eugenics Society into the early 1930s, though by this point in its history its emphasis on sterilization was being challenged somewhat by events in Germany and declining populations. (He also had been living in the London house abandoned by his mother when she followed Havelock to Suffolk.) The network of connections allowed Laffite to write his most famous piece, in 1940—though it was not on population policies. Rather, he had found a patron enraged by the treatment of German aliens in a martial England. Lafitte wrote “The Internment of Aliens,” blasting his country for its poor treatment of refugees and immigrants.

Ellis didn’t live to see that work. He died on 8 July 1939. Presumably, it was a heart attack.

Delisle was still relatively young, in her early fifties, but without the love of her life and her two sons distant. Paul would eventually emigrate to Australia and become a professor of psychology; Francois continued his work with PEP before joining the sociology faculty at the University of Birmingham. I’m not sure what she was doing during this period; she seems to have stayed close to home, and doesn’t seem to have written much: the memoir of her life with Havelock was published some seven years later. Continued sales of Ellis’s books comprised her income. Of herself she would write, “Cool reasoning is not my strong point,” and her son Francois would recall, she became “a very deaf, increasingly crotchety, emotionally and financially insecure widow . . . endowed with a florid hysteric personality, a prey to anxieties both genuine and irrational.”

In 1946, she published an pseudonymized editor of “Friendhsip’s Odyssey,” the book about her relationship with Havelock Ellis, though it became entangled in a bankruptcy that set her back financially. By the 1950s, she published a bit more, and also encouraged autobiographical writings on Havelock—well, kind of encouraged, she wasn’t exactly consistent, protective but also aware that new interest in Havelock would help sell his books. Various versions of her and Havelock’s memoir—introduced by her—appeared through the 1960s. In 1953, she moved to London, to be closer to Francois, then in 1958 followed him and his family to Birmingham. The early 1970s proved an especially difficult time. Her second son, Paul Lafitte—as he went by—died in 1972. Her grandson, Francois’s only child, Nicholas, committed suicide in 1970. In 1974, she published The Pacifist Pilgrimage of Francoise and Havelock.

She died unexpectedly that year, on 5 December 1974. She was 88.

Francoise Delisle’s Forteanism raises again the vexed question of who counts as a Fortean—especially for her lover, Havelock Ellis, the more famous of the couple. Ellis’s name was used in advertising for the Fort omnibus edition—put out in 1941—and was included on Fortean Society letterhead, the side of which was a list of posthumous Forteans including such luminaries as Oliver Wendell Holmes and Clarence Darrow. In the past, commentators—including me—have wondered if Holmes and Darrow were really members of the Society. No definitive proof have come to light, but it has become clear the Thayer only listed names of people who gave some affirmative response to request of joining the Society; that didn’t mean they knew of Fort, or supported Forteanism in anything but the most abstract way. But their connection was not purely Thayer’s fantasy. That would seem to be the case of Ellis, too.

The question then arises, when and how did Ellis and Delisle become attached to the Society—given that there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that either of them read or were enthusiastic about Fort before joining the Society. There are two possible routes. The first is through Dreiser. I have found no evidence that Dreiser knew Ellis, but he admired him greatly, knew people who did know him, and both belonged to a group to fund Emma Goldman’s memoirs. It is no surprise that Dreiser would have felt affection for Ellis, seeing as both were fighting against the same Victorian sexual mores—Dreiser in his (philandering) life and his (often censored) writing, Ellis moreso in his writing, though his life was unusual enough. At the first meeting of the Fortean Society—first and only, in January 1931—Dreiser suggested that Ellis should be a member of the Society as well. Thayer very well may have taken up Dreiser’s suggestion. The other possible route is through Harry Benjamin, the sex researcher and a friend of Thayer. Benjamin visited Ellis in 1937, two years before Ellis died and just after Thayer restarted the Fortean Society. He may have facilitated some correspondence or at least put in a kind word for Thayer, disposing Ellis to join. This second route is suggested by Thayer not using Ellis’s name until 1940—and including Ellis in The Fortean 3 (January 1940), listing him among recently passed Forteans, with Darrow, Harry Leon Wilson, and Felix Riesenberg.

Delisle herself had much more extensive connections with the Fortean Society—if not an a particularly strong attachment to Fort—a connection that is not shown well in Thayer’s magazine. Indeed, she is mentioned only twice. The first, and most informative, came in Doubt 17, published around March 1947. Under title “Russell Grist”—referring to the activities of Eric Frank Russell—Thayer noted that the British membership rolls continued to grow, and highlighted the addition of “Francoise Delisle, author of Friendship’s Odyssey, an autobiography which relates her long association with Havelock Ellis.” Thayer notes her joining is “recent,” suggesting that her connection to Forteanism and the Fortean Society was not (directly) through Havelock Ellis. In retrospect, it seems that Russell may have reviewed her book, which sparked some correspondence between them. The problem is I have not actually found a review (if it exists it likely ran in N. V. Dagg’s “Tomorrow”) nor does the extant correspondence between Russell and Delisle date back far enough to confirm this speculation.

Still, the suggestion has a basis in evidence. In December of 1946—before Thayer announced her joining, but presumably after she had accepted membership—Delisle met the paranormalist Harold Chibbet. She does;’t seem to have been in contact with any other Fortean besides Russell and, according to Chibbet, that was through Russell’s review of her book. Chibbet wrote to Russell,

“I have at long last called upon our fellow Fortean, Mme Francoise Delisle. She resides not far from Tally Ho. Corner, and is easily accessible from this palatial residence. A very interesting lady, with no inhibitions. Enthralled by my descriptions of your worthy self, which were worth at least a guinea a box. I’ve even lent her SINISTER BARRIER to read. Aged 61, and with a French accent you can cut with a knife, although she has lived in this country for thirty years. Married twice before she commenced her association with H.E. Has two sons by her earlier husbands, one a psychologist and divorced. The other still happily married. Apparently quite amused at her psychologist son’s attempt to convert her to Christianity. [NB: This would have been Paul.] Is very grateful to you for your favorable review of her forthcoming book, which I have not yet seen. Has shelves and shelves full of H.E.’s sex books, which I am borrowing and reading with much avidity. I’ll extract all the juicy bits and send them to you. She is very interested in psychic research, and is a member of the S.P.R. [NB: Society for Psychical research]. Rather deaf, and speaks in the loud voice so common to such afflicted persons. Altogether an interesting personality. Thanks for the intro.”

Correspondence between Delisle and Russell exists starting a year later, in December 1947, lasting into the early 1960s. The letters are all short, all from her to him, and focused mostly on business. The nine letters make clear that Delisle was having money problems and was usually late paying her dues. (Thayer was just happy someone was paying, on time or not: in 1951 he wrote to Russell, “Francoise Delisle, for paying her dues, is a lady.”) She was writing, too, though having trouble publishing her work. She mentions an almost-complete book on motherhood that never appeared. Another work, on sex, Russell helped her edit, and she placed in “The Journal of Sex Education.” (I haven’t found the article.) When she was having trouble with reprints of “Friendship’s Odyssey,” Russell put her in contact with his own agent, Gerald Pollinger. Nonetheless, it gives a sense of her Forteanism, as well as her connection to other Forteans, mostly beyond the Fortean Society.

The first one included 5 pounds, not only for dues, but also for copies of Thayer’s “Rabelais for Children”; Alfred Jay Nock’s “Our Enemy the State”; Russell’s own “Sinister Barrier,” and John Millis’s “Glacial Period and Drayson’s Hypothesis.” She had not seen Chibbett since that initial meeting—though she found him fascinating—but clearly she was taking to the Fortean Society—all these were books offered for sale through the Society. She was also interested in connected movements, asking for the address of “New Frontiers,” a magazine recently started on paranormal phenomena. She was hoping to have an article placed there—this was the one that eventually ended up in “The journal of Sex Education.” Already, she had sent it to N.V. Dang at “Tomorrow”—showing her interest in psychical phenomena—and he had held onto it for three months before deciding it would not fit in his magazine.

Apparently Russell wrote her back, informing her New Frontiers had already closed its shutters—the magazine was very short-lived, which did not surprise her. Russell also shared with Delisle the magazine “Different,” which was being put out by former cult leader and current Fortean, science fiction writer, and defender of conservative poetry, Lilith Lorraine. Delisle wasn’t sure she’d actually read the magazine, but was interested to see it. Three months after that first extant letter, Delisle wrote again, sending in more dues, buying more books—another copy of “Sinister Barrier,” Silvio Gesell’s book on economics, and several tomes by world citizen Scott Nearing—again all interests of the Fortean Society. She was missing Chibbett, and worried she had somehow offended him. (As far as I know, he never met her again.) Whether she really needed two copies of Russell’s book, had forgotten the earlier order, or not had it sent to her is unknown. But it does show she ha dan interest in Fortean science fiction. She also seems to have developed a fondness for Russell, continually asking after him, and his work.

Indeed, her next letter to him, dated Valentine’s Day 1950, draws together a number of Fortean strands. (The tardiness seems to reflect her poor financial situation.) She is sad to hear that Dagg had closed “Tomorrow,” and wondered what he had turned to. She wondered, too, what Russell was working on, and if his recent move to Liverpool was a sign of good fortunes. The shuttering of “Tomorrow” meant that Russell’s series of articles on the moon ended. Some of this came out in the post on James Blish, and more when I get around to writing up Russell—chronologically, it is about time, but he’s such a large figure, that may have to wait—the point is that Russell was doubting the wisdom of aiming rockets at the moon in general, since the satellite was likely dead (he doesn’t seem exactly wrong from today’s vantage point) and the calculated distances to it might be incorrect.

She had also become intrigued with flying saucers, having read about them in the periodical “Enquiry.” These articles she offered to Russell—if he had not already seen them—as exemplary Forteana. She also reflected on Lilith Lorraine, who had become a topic of conversation in Doubt 27 (September 1949). There’s no record of Delisle’s reaction to “Different,” but apparently it intrigued her enough that there was correspondence between the two women at least once since Russell had shared the magazine. Apparently, Delisle had sent something to Lorraine—something to be published? a clipping? a reference?—who—according to Delisle—offered a “most weird” reaction: “liking it but saying that it was best not to open people’s eyes to the matter there discussed. Well! Well!”

What really upset Delisle, though, was the same point that irritated Thayer and Russell. Lorraine, under the aegis of “The League for Sanity in Poetry,” had sent a letter to Congress protesting Pound’s winning the Bollinger Award. In “Different,” she published an article by science fiction writer and fellow-conservative defender of poetry Stanton Coblentz lambasting Pound. Thayer reported the goings-on in “Doubt,” and published a short essay by Russell defending Pound: the arguments against Pound, he said, were ideological, not aesthetic, and should be dismissed as demagoguery—and this without Russell himself having read Pound’s “Pisan Cantos.” Del isle, continuing from her denunciation of Lorraine’s hypocrisy, wrote, “And her attitude to Pound takes to cake, while your defense is excellent.”

The density of the letter must have appealed to Russell, because the nee letter from Delisle is dated only a week later, and is a response to something he wrote in the interim. She was gad that his move had been for good reasons, and was hoping to move closer to her own son in England—Paul was by now in Australia—but doubted she would succeed, and so took succor in her garden. The rest of the missive dwelt on Fortean topics: Dagg and flying saucers. She was distressed at whatever Russell had told her about Dagg (perhaps a comment on his Fascistic tendencies?) and replied that she was well aware of its financial difficulties and dropping subscription rates. She had scrimped some of her own money and sent it to him to help keep the magazine aloft, without ever having heard a response; she wondered if there were deeper troubles and was still sad to see it go, even as she acknowledged it had become quite strident.

She called Russell’s attention to “The Mystery of the Flying Saucers”—which seems to have been Gerard Heard’s “The Riddle of the Flying Saucers”—as well as two articles by him, feeling “positive [they] would interest Forteans”—but she could not provide them (and wanted her copies of “Enquiry” back). The articles were too long to type up, and she could not afford to pay someone to do the work for her. (The letter is confusing, and the articles by Heard may have been the same ones as those that appeared in “Enquiry.”) At any rate, she recommended that Russell buy extra copies of the pieces for dissemination among Forteans. Heard argued that flying saucers were driven by insect-like beings from Mars, and apparently something about this idea resonated with Delisle.

It was at this point—the height of Delisle’s interaction with Russell and the Fortean Society—that her name appeared again in Doubt, the second and final time. Doubt 31 (January 1951) carried notice of her activities under the (sexist) title “Havelock Ellis’ Lady.” Thayer noted that her book “Friendship’s Odyssey”—unnamed by him—would soon appear in the U.S. He then reprinted a letter of hers from “Peace News,” 18 August [1950]. She tore into the war-mains machine, and the noble ideologies put in its service—we must defend freedom against terrorism, going so far as to say that being overrun by communists was preferable to another war: “Surely, . . . it is better even to die at the hands of terrorists than to become one. And is not war terrorism in excess? With due apology to Shelley, it is as if terrorism creates ‘from its own wreck the thing it contemplates.’” Delisle went on to point out that she lived under German occupation during World War I, and her family did so under World War II—and both were preferable to war itself. Politics, then, as well as psychic phenomena and flying saucers—these were the connections between Delisle and the Fortean Society, she comfortably nested among the left-libertarian strand of the Society’s political continuum.

It would be more than two years before she got in contact with Russell again—some three years since their last contact. She was sending in her dues, presumably for the first time in years, and explained her tardiness of her recent move to be near her son—a cost-cutting measure, which also might explain her reluctance to send in dues earlier. (Reluctance—or inability?) Still, she wanted to keep up with Fortean happenings and told Russell to make certain her change of address was noted. “Always interested in Doubt and the Fortean Society,” she said.

Which was the last note of her interest. Four years would pass before she wrote Russell again, and then another five—so, they reached out to each other in 1957, two years before the end of the Fortean Society, and after Russell had begin to withdraw himself from it, and 1962, three years after it had passed and Russell’s interest in Forteana had dwindled to a small flame. These letters all deal with Delisle’s publishing troubles, and her finally getting out “Friendship’s Odyssey” in two volumes, as she had always wanted it, with the pseudonyms stripped away.

And that was it, whatever forces motivating her Forteanism no longer on display, at least publicly. She turned to her immediate family and continued to nurture the memory of Havelock Ellis so that he and his work—and hers—in birthing a more modern, less repressed society would be remember. So that his work of bringing to light all sorts of damned facts and placing them in orthodoxy should not itself be damned.