Francis Amadeo Giannini seems to have been his name, although some sources give it as Amadeo F. Giannini. He was probably born in the late 1800s or early 1900s—maybe on exact a date as 1898, as the Oregon death index has someone by that exact name being born (somewhere) on 3 October 1898 (and dying in Multnomah County on 26 November 1973). But besides the name—which was not uncommon—and the approximate date of death, there’s nothing else to suggest this is the same Francis Amadeo Giannini who joined the Fortean Society in 1944, least of all the location of Portland, Oregon.

There’s only one other bit of information that gives me pause before saying that he joined the Society and wrote under an assumed name. And that is two cards from the Associated Press, Name Card Index to AP Stories, 1905-1990. A 6 January 1932 card reads

Giannini, Francis A. Boston

Is arrested on charge of unlawful entry by a house detective at Plaza Hotel; is said be a lecturer [sic] on astronomy 1-6-32 NLA48

Is held in $1,500 bail for hearing tmrw when arraigned on charge of unlawful entry 1-8-32 NLA22 DLA1

Is held in $2,500 bail for trial inspecial [sic] sessions on charge of unlawful Entry [sic] 1-14-32 NLA4

A card from 6 May 1932 read

Giannini, Francis A. 2

Giannini, who told a probation officer he had lectured before the National Academy of Science in Washington and at several large Eastern colleges, is sentenced to Sing Sing for unlawful Entry [sic]. 5-6-32 DL32

For reasons that will become clear below, the person arrested in 1932 is almost certainly the same one who joined the Fortean Society and later wrote a book on cosmography.

In the spring 1944 issue of The Fortean Society magazine (no. 9), Thayer announced a new member—who, like other Forteans had invented a new conception of the universe--

“The Society has belatedly come upon the Giannini Universe, through the courtesy of its creator, Francis Amodeo Giannini, who recently joined us. Its details, to be found in MSS only, were ‘first presented in 1927,’ in a paper headed: ‘Physical Continuity of the Universe and Worlds Beyond the Poles.”

Apparently, Giannini also sent in clippings from The Los Angeles Evening Express (15 August 1928) and the Boston Evening American (1929), both of which described the author as “the first man in 500 years to attempt to give a greater picture of creation.” So, somewhere out there is newspaper proof of Giannini’s existence.

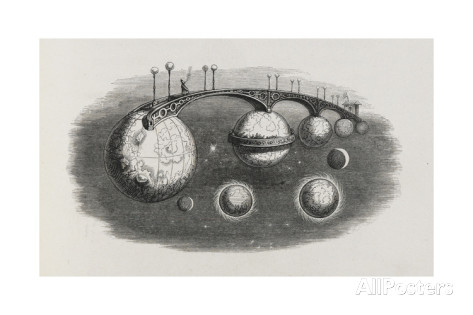

As Thayer explained it, Giannini contended that there was a bridge (of ice, land, or water) connecting each of the planets at their poles, Earth to Mars to Jupiter, say, and Earth to Venus to Mercury. Giannini said that one day in the future, we would think nothing of walking or driving or flying from one planet to the next. The details are, of course, very different, but the basic idea is close to the cosmography Fort put forth in New Lands, with the planets close to one another and the stars something of an illusion. Thayer said that he hoped to print excerpts of the manuscript from time to time but never did.

According to Giannini himself, writing in 1959, he came to the idea of an interconnected universe while walking through the New England woods in October 1926. The images came to him via ESP. So impressive was the vision that he took to buttonholing potential patrons—he was, in his words, a “new Columbus” in search of a Queen Isabelle. He spoke with Thayer’s bête noir Howard Shapley, at Harvard, with R. A. Millikan in California and Harold Wilkins, just before he left for the Arctic on an expedition financed by Hearst. He spoke with Edwin E. Slosson, Director of the Science Service. He talke with journalists, archbishops, and naval officers. He even beseeched his namesake, A. P. Giannini, president of Bank of America, to fund him on a flight to South America so that he could prove that the earth did not end, but extended on and on. Nothing came of his begging, though, and, after being arrested, he wasn’t heard of again—at least by me—until he joined the Fortean Society.

He popped into public view again in 1947, riding the publicity that surrounded Robert Byrd’s exploration of the South Pole. On 2 February 1947, columnist Bob Considine wrote up Giannini’s ideas for the Washington Post, using as a hook Giannini’s exhortation that Byrd should continue past the South Pole and onto Mars. Considine—who would write a biography of Robert L. Ripley in 1961—made it clear he thought Giannini was a kook. A month later, on 30 March, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat devoted a page to him. (I have not seen this article.) Giannini seems to have drifted from the Fortean fold by this time, as Thayer only heard about the articles from other Forteans who sent in clippings. (Doubt 18, July 1947, 268.)

Probably, Thayer tried to contact Giannini in the wake of this publicity—and the continued stories about Byrd. But, if so, he had no luck. In Doubt 25 (Summer 1949), Thayer listed Giannini among the “Lost Sheep.” “Who can help us find any of these MFS?,” he asked. But no one responded—Giannini remained a lost sheep, at least as far as the Forteans (and I) could tell.

But he was not completely cut off from the Fortean world, even if he was from the Society. In 1959, he published a book through a vanity press—Worlds Beyond the Poles. Supposedly, this was an expansion of a 1958 publication “Physical Continuity of the Universe and The Worlds Beyond the Poles: A Condensation” (which is the same title as the manuscript he presented to Thayer), but I have seen no sign this earlier work was ever published. It was in Worlds Beyond the Poles that he Giannini gave the history of his ideas, and his attempts to get others to support him. The list of dedicatees is bizarre, including A. P. Giannini, who had refused to give him money, Wilkes, who dismissively said he’d check out his theories, Byrd, who Giannini mischaracterized in order to find support for his theory. And Ray F. Smith—which just happens to be the name of a Fortean active in the late 1950s. The connection remains obscure.

Some Forteans were very careful about their data, and the ways that they constructed arguments, even if the arguments themselves were nonsensical or meant in fun—indeed, Fort had pioneered this method. Giannini did not belong to this class of Forteans. Even potentially sympathetic chroniclers Walter Kafton-Minkel (in Subterranean Worlds, 195-6) and Joscelyn Godwin (in Arktos, 120-123) are abashed by his carelessness with facts, mixing up expeditions to the north and south poles, inventing reports, taking quotes out of context—not too much his vagueness, bad habit of referring to himself in the third person, and generally difficult syntax. His attempts to describe what a physically contiguous universe would look like—a giant donut? a moebius strip? a vast plains?—are confused.

Nonetheless, he found support—from an expected place, on retrospect. Raymond Palmer, science fiction editor, peddler of metaphysical marvels, and champion of flying saucers, reviewed the book in his magazine Flying Saucers, finding in it support for the theories of Richard Shaver, which posited that the earth was hollow, with potential entry points at either of the poles. (Fort had played around with the idea of polar civilizations as well.) Giannini suggested that Byrd had actually seen these lands beyond the Poles, and had described them in a secret diary, telling of a vast and teeming jungle.

Unfortunately for Palmer, his readers could see the many errors that Giannini had made—including transposing Byrd’s exploration of the South Pole to the North. Giannini wrote into Palmer’s magazine and suggested that Byrd had made a secret trip to the North Pole while he was supposed to be in the South—and so Giannini had not confused his facts at all. Palmer, always willing to play both sides of a controversy, went back on forth on the mater, as Ralph Nadis notes in his biography of him (The Man from Mars, 232-6).

More to the point, Giannini’s contentions became facts often cited by later Forteans, hollow earth enthusiasts, and flying saucer buffs. And so even if basically nothing is known about the man, his ideas persist, even if only on the fringes.