Well, “minor” in a couple of senses. For two of these people, I could find no reliable information. They may have been the world’s most devoted Forteans, but I have no record of it. The third was a devoted Fortean, at least judging by what was in Doubt, but, again, there’s very little information available—which is better than no information, however! Finally, the fourth Fortean considered here is a well-known science fiction fan, and there’s an abundant of information on him—but he was something less than a devoted Fortean, more an interested observer or, better said, a meta-Fortean.

Vincent Ford was credited four times in Doubt between 1943 and 1947. The first referred to an Iowa man who started a fire by rubbing his feet together—twice (June 1943); the second an apple tree in Indiana that bore a second crop of fruit (Winter 1945); the third reported on some UFO incident: it came in Thayer’s bitter denunciation of the subject, and Ford’s name was one of many on a long credit list. (October 1947). He also got a call-out in 1944. Thayer had roused himself to engage in one of his infrequent Quixotic quests and had Forteans checking libraries across the country to discover if Alfred Henry Barley’s book on the Drayson problem was available. Vincent Ford was among those who checked on a library or libraries and reported back. The name is otherwise too common, biographical details too sketchy (did he perhaps live in the Midwest? But how old was he?) to make further research impossible.

Another too-common name with too-little biographical information belongs to Fortean Ross M. Colvin. Colvin received only two mentions in Doubt, both related to the Drayson problem. Like Ford, in 1943 Colvin searched through some number of libraries for Draysoniana and reported to Thayer he had found none. (As it turned out, only the Library of Congress held Barley’s book.) But, Colvin had made an earlier discovery. While looking into libraries for material on Drayso he somewhere came across two letters from Drayson himself to a Clara Moore written in 1890 and 1891. They reveal that Drayson was fed up with “Cheap Jack” professors whose “real business seems to be to obstruct truth” and expressed sympathy with Moore’s interest in John Ernst Worrell Keely, a Philadelphia inventor who claimed to have created a new kind of engine. (Both Keely and Moore thought that the engine might run on ether.) As it happens, Charles Fort wrote about Clara Moore and her support of Keely—it was the last item in his last book, Wild Talents. “Thus we have Drayson on Fortean territory, which is very interesting, to me, at least,” Colvin wrote. Thayer was ecstatic and called Colvin “Our Worshipful Brother.” He said nothing else about him, though. I cannot find where the Drayson letters are held, and so cannot begin to search for Colvin: perhaps London, perhaps Philadelphia. There was a Ross M. Colvin living in the Philadelphia area until 1940, and perhaps that was him, but he was in the military in 1943, and stationed I-know-not-where. Just not enough information.

Harold W. Giles, the third Fortean considered here—him, I know where he lived. Buffalo New York. Indeed, he seems to have spent his entire life in upstate New York. Giles was born 1 July 1903 in Lockport Ward 3, Niagara, New York. His father was a laborer, variously captured by the census as a brass worker, a sweeper, and a caretaker. Chrestopher Giles was about 45 when Harold was born; his wife Elizabeth was twelve years his junior, and so the family kept growing for the next seven or eight years, Harold joined by three younger sisters. (He may have had older siblings who had already left the house, too.) He attended college in the mid-1920s—somewhere nearby, since he lived at home—and by 1930 was an insurance agent. Sometime between 1935 and 1938 he opened a bookstore, and it was as a bookseller that he made his living for the rest of his life. He died in Buffalo in 1983.

Giles was one of the most frequent, and long-acting, contributors to Doubt. He received at least 31 credits between 1943 and and 1958 (so issues 7-57, out of 61). He was a close reader of Fort, detecting that the omnibus edition (page 423) drops a line from New Lands (page 127). Thayer wrote, “Brother Giles is the mainspring of Forteanism in Buffalo, where he operates a bookstore in 67 West Chippewa Street.” By issue 12 (summer 1945), Thayer was giving Giles room to spread his wings and expanding his encomium. “The good Fortean not only gives us complete coverage of his local press (Buffalo) on quakes, volcanoes, propaganda and more abstruse Forteana, but he is alert for old books of Fortean significance, and for errors in the text of THE BOOKS, and in the pages of Doubt. More--he has made his bookstore at 67 West Chippewa Street, a center of Fortean interest and activity, always keeping a supply of THE BOOKS and of back numbers of the magazine on hand. The ‘second-hand bookstore’ is the logical gathering place for Forteans. If our ‘Religion of Self Respect’ has churches and temples, those are they. The brotherhood of the musty tome doffs its skull-cap to no ‘authority,’ not to Allibone, Dibdin or Book Prices Current, much less to Milliken, Compton and Shapley. When the Society has one Giles in every town of 50,000 and over, the world round, Your Secretary will lay down his crozier (with its runic inscription) and go Hellwards in full confidence of his reward—more data from Giles.”

That issue included a long column of material Giles contributed: about a priest struck by lightning, a blind man with a sick wife and child classed by the draft board as 1A; a bird that hit a plane in the dead of night; Draysoniana; an Italian exiled by Mussolini who refused to endorse the U.N.; comets that cannot be seen by amateur telescopes; Einstein admitting he was not a great mathematician: that is to say, all the Forteana Thayer liked, from anomalies to political and religious happenings.

Giles received another extended column in Doubt 28 (April 1950), in which he made winking predictions for the new year:

“M F S Giles took a gander at the future and decided to share the following with us:

I am aware that in making the following predictions of trends and events for 1950, I am acting contrary to the advise of a certain New York psychiatrist, who bids us live in the present, and (in surprising consonance with the 6th Chapt. St. Matthew) take no heed for the future. See a recent issue of TIME, wherefrom my intrepidity will appear all the more remarkable, inasmuch as the said psychiatrist is credited with several remarkable cures, (at $1,000. each); among them the curing of a fellow physician of the drug habit and an ex-cabin boy of homosexuality. Of course, it is easy to understand how a practicing physician could afford such expensive treatment, but certainly it isn’t every cabin boy (or ex-cabin boy either) who has a thousand dollars . . .

“But a fig for psychiatry! What have I to lose?

“I predict that during 1950:

“The stock-market will fluctuate, as the elder Morgan once predicted on another occasion.

“Prosperity will be general, but domestic finances are likely to be subject to a certain stringency, the more especially among those in the lower income brackets.

“The international situation is likely to become tense; but a marked tendency to the contrary is to be looked for if a sufficiently plausible publicity can be given to a threatened invasion of the earth by beings from another planet.

“The rich (with a few exceptions) will become wealthier; and, in consequence, the poor (with even fewer exceptions) will become poorer.

“The budget will, with a high degree of probability, remain thruout [sic] the calendar year, unbalanced.

“Science will make vast strides during 1950. And the people looking for adequate housing will cover a vast amount of territory, too.

“The number of people who will, in unpremeditated frenzy, commit suicide during the year is not expected to vary at all from the number giving [sic] the percentage of the population who made away with themselves in previous years.

“The condition of the arts will remain deplorable, since most of the artists (nowadays) appear to be as oblivious of direction as a whirling dervish.

“As for women’s styles, I venture to say that they will be becoming to some; and to others, only moderately so; or not at all.

“The Church will make gains in membership during the year, the more especially in the larger cities, where numbers tend to beget numbers; in the rural districts, a larger percentage will be likely to remain pagan.

“The State, in concert with its other self, The Church, will continue to foster the fiction that they are twain, essentially distinct, entities.

“Life Insurance Companies will enjoy a year of mixed blessings, Mortality will be low, (unless, of course, the war flares up with unexpected fury). Income from investments will be stable; but due to the general prosperity, fewer policy-holders will borrow from the companies at the customary high rates of interest; and hence, revenues may be low. However, more insurance will be written; and more capital come under the control of companies, who will, in consequence, become more influential than ever.

“The world population, despite war, disease, and a mounting toll of traffic accidents, will continue to increase; but not to any embarrassing extent as yet. No more than the usual number will starve; and flight to other planets will not become exigent; indeed, thee is not a little doubt that it may not even become feasible.

“Advertising will become more widespread and blatant than ever. And more money will be appropriated for education, tot he end that a larger percentage of the population will be able to read advertisements for themselves, as issued. What with radio, moving-pictures, and television, I cannot say that this trend will continue much beyond the present year. But for the immediate future it seems assured.

“On the other hand, that which is occult will, in all likelihood, remain hidden, unless perchance it should be revealed.

“As for the weather, the chances are that it will prove disappointing--all prognostications (except, of course, this one) notwithstanding.

“HAPPY NEW YEAR! H. W. Giles”

Again in June 1952 (number 37) he contributed a long piece, titled “Visits with the Professor. I. Physics as Bodies in Motion.” (Note there was never a II.) It recorded a mock conversation with a physicist who argued against the prevailing wisdom that most of matter was electrical (E=MC^2). The professor didn’t even believe in matter: everything was just bodies in motion. He went on for a while, arguing space and time were abstractions, that motion was the most basic fact—an abstruse set of reasonings. At the end, the physicist’s interlocutor—presumably Giles himself—remarked that Samuel Butler thought there was only one body: the universe itself. How did that square? The physicist would not be trapped: like Giles, he was a true Fortean. Giles quoted Butler, but the point about the universe being a single entity was just as surely Fort’s. And the physicist replied. “I never said that any of those bodies were real. I wouldn’t know what you meant by that. What is reality?” This was the Fortean bottom line; whatever the reasoning—and Giles’s was hard to follow—the conclusion was, reality is not what we think it is. Giles, then, was a thoughtful and playful Fortean—the two qualities usually went together—and it is a pity there is not more known about him.

We do know a lot about the fourth Fortean, Everett Franklin Bleiler. He too was playful and thoughtful, and showed some interest in Fort, though not so much the Fortean Society—and his interest does not seem to have been as intense as Giles’s. Bleiler was born 30 April 1920 in Boston Massachusetts to Joseph (37) and Rose (33) Bleiler. Joseph and Rose were natives of the state, both their sets of parents having emigrated from Germany. Joseph was a farmer. Bleiler attended Boston Latin and went to Harvard, concentrating his studies on anthropology. He enlisted in the army on 1 May 1942, his occupation at the time given as actor. He was 22.

Bleiler was an extensive reader. In a 2005 interview, he remembered, “From high school days on I used to buy books of all sorts that looked interesting and read them. Sometimes this paid off, sometimes it didn’t. While I had very little money, it was always possible to buy books cheaply. Americana was costly, but fantastic fiction was readily accessible at low prices.” In the same interview, Bleiler said that he had hoped to get into academia, but for whatever reason, that ambition went unfulfilled. Still, his life was a paean to intellectual work. In addition to the books on science fiction and fantasy he produced, Bleiler wrote introductions to the German and Japanese languages and did a number of translations. He also produced one archeological monograph.

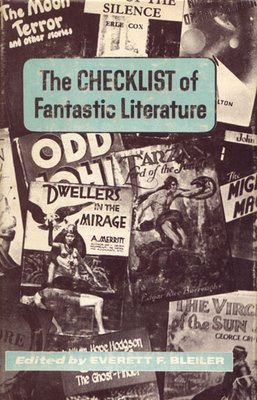

Somewhere in all of his reading, Bleiler came across Fort and joined the Fortean Society in the early 1940s. He contributed at least one item—but Thayer ran out of space to get to it, and then never followed up. And he applied his intense scholarship to the field of science fiction and fantasy, creating one of the first bibliographies of the genre in 1948, an overview of some 500 texts written since 1800—a wide-ranging assortment, including works by the likes of Virginia Woolf. The science fiction publisher Shasta put out the book, and Thayer—then still on the science fiction bandwagon—raved, “Here is a field day for Forteans who, like Fort himself, delight in elaborating upon damned themes. The editor and chief compiler is MFS Bleiler, the publisher and prefacer is MFS Korshak, the dedicatee is MFS Shroyer, ‘all members of this club.’ The volume is THE CHECKLIST OF FANTASTIC LITERATURE, a Bibliography of Fantasy, Weird, and Science Fiction Books Published in the English Language, and if we were to match its “Listing by Author” against the Society’s rolls, we should certainly find upwards of twenty members represented ... YS is here, Russell and Abe Merritt--and Doreal and Derleth get editorial acknowledgement for assistance in the work. It was worth doing. It has been well done. Get your copy from the Society, bound in cloth, xvii and 455 pp. $6.00.”

By the early 1950s, though, Bleiler was losing interest in science fiction and fantasy writing. He took a job as an editor with Dover—admittedly overseeing the republication of some old fantasy, such as Robert W. Chambers’s stories—and slowly drifted from the field for the next quarter of a century. Exactly how interested he was in Fort during the 1940s is unclear from the record we have; but, at any rate, like a number of Forteans, he replaced whatever enthusiasm he had with other work.

Beginning int he 1970s, he returned to science fiction—and bibliography, eventually producing three annotated checklists of fantastic literature, providing later readers with pointers to literature that they might have missed as well as summaries of works that, by then, were almost impossible to obtain, particularly the stories published in pulp magazines of the mid-century. (He also contributed to other bibliographic projects, particularly relating to crime stories.) The books were The Guide to Supernatural Fiction: A Full Description of 1,775 Books from 1750 to 1960, Including Ghost Stories, Weird Fiction, Stories of Supernatural Horror, Fantasy, Gothic Novels, Occult Fiction, and Similar Literature, with Author, Title and Motif Indexes (1983); Science Fiction: The Early Years: A Full Description of More Than 3,000 Science-Fiction Stories from Earliest Times to the Appearance of the Genre Magazines in 1930 with Author, Title, and Motif Indexes (1991); and Science-Fiction: The Gernsback Years: A Complete Coverage of the Genre Magazines Amazing, Astounding, Wonder, and Others from 1926 Through 1936 (1998). The last two were compiled with the help of his son, Richard.

These compendium helped to highlight and sustain interest in Fort. Bleiler pointed out what he thought were Fortean influences in various stories—and included these in the index, allowing for the later reader to get some sense of the breadth of Fort’s influence on science fiction in the middle part of the twentieth century. They also included Bleiler’s mature thoughts on Fort. In the 1970s, tyne science fiction fan—and Fortean critic—Sam Moskowitz had republished Fort’s 1906 story “A Radicle Corpuscle,” which late out in the terms of fantastic fiction Fort’s monism. Bleiler included a summary of this story—“an amusing sketch”—in his second compilation, with an added plug: “Apart from Fort’s ‘serious’ work, which is often brilliantly stated and fascinating, though certainly not acceptable, his novel The Outcast Manufacturers (1909) is worth reading,” as was Moskowitz’s essay on Fort’s short stories, which were otherwise unknown.

Later in the tome, in a section on background material, Bleiler deals with Fort’s non-fiction, under the heading Book of the Damned:

“An eccentric philosopher-historian, Fort devoted his light to collecting and collating information about odd manifestations that he insisted had been ignored by orthodox science, yet deserved attention in suggesting new, better formulations. He described his data as ‘damned,’ i.e., consciously and systematically excluded from discussion, suppressed because they do not fit established orthodoxy. In a series of four books--The Book of the Damned (1919), New Lands (1923), Lo (1931); sic; Wild Talents (1932),—Fort coordinated a vast amount of ‘rubbish of science’ that has served as a data bank for writers, for cranks, and charlatans. The flying saucer proponents, for example, draw heavily on Fort’s work. Although Fort often concealed his theoretical position in deliberately outrageous conclusions, he was essentially a belated philosophical idealist, a monist who held that manifestations are reversible to oneness, and that phenomenality is half-way between existence and non-existence, being the result of a driver toward individuation. Like the early nineteenth-century idealists he held that the act of recognizing self immediately created a non-self, and thereby host of relationships. On a more material level, he seems to have held that the universe is a ‘living’ self-adjusting mechanism with as yet unrecognized parallelisms and interchanging mechanisms running through it. Thus, earth and the individual are not isolated entities, but members of complexes affected by currents from larger or other entities. His data are intended to be proofs of such relationships. In the present volume [Book of the Damned] Fort concerns himself mostly with strange objects that purportedly have fallen from the sky: rains of fish and other marine life; falls of frogs; odd cloth-like substances, unusual meteorites; appearances in the heavens, like luminous flying objects; thunderstones; artifacts found in circumstances of great geological age; underwater lights; astronomical viewings not generally accepted; and astronomical fiascos. Most of his data are derived from nineteenth century journals and newspapers, which, although collated whimsically, are cited precisely. The obvious irony, of course, is that Fort, who distrusted almost anything stated by an academic, had an enormous faith in the amateur printed word—though he himself was a newspaperman! Fort became a source of ideas in science-fiction in the 1920s and 1930s. The term ‘Fortean’ was later applied to such work. Writers on the whole ignored his philosophical ideas, but found his fact chains useful.”

Everett Franklin Bleiler died in 2010.

Vincent Ford was credited four times in Doubt between 1943 and 1947. The first referred to an Iowa man who started a fire by rubbing his feet together—twice (June 1943); the second an apple tree in Indiana that bore a second crop of fruit (Winter 1945); the third reported on some UFO incident: it came in Thayer’s bitter denunciation of the subject, and Ford’s name was one of many on a long credit list. (October 1947). He also got a call-out in 1944. Thayer had roused himself to engage in one of his infrequent Quixotic quests and had Forteans checking libraries across the country to discover if Alfred Henry Barley’s book on the Drayson problem was available. Vincent Ford was among those who checked on a library or libraries and reported back. The name is otherwise too common, biographical details too sketchy (did he perhaps live in the Midwest? But how old was he?) to make further research impossible.

Another too-common name with too-little biographical information belongs to Fortean Ross M. Colvin. Colvin received only two mentions in Doubt, both related to the Drayson problem. Like Ford, in 1943 Colvin searched through some number of libraries for Draysoniana and reported to Thayer he had found none. (As it turned out, only the Library of Congress held Barley’s book.) But, Colvin had made an earlier discovery. While looking into libraries for material on Drayso he somewhere came across two letters from Drayson himself to a Clara Moore written in 1890 and 1891. They reveal that Drayson was fed up with “Cheap Jack” professors whose “real business seems to be to obstruct truth” and expressed sympathy with Moore’s interest in John Ernst Worrell Keely, a Philadelphia inventor who claimed to have created a new kind of engine. (Both Keely and Moore thought that the engine might run on ether.) As it happens, Charles Fort wrote about Clara Moore and her support of Keely—it was the last item in his last book, Wild Talents. “Thus we have Drayson on Fortean territory, which is very interesting, to me, at least,” Colvin wrote. Thayer was ecstatic and called Colvin “Our Worshipful Brother.” He said nothing else about him, though. I cannot find where the Drayson letters are held, and so cannot begin to search for Colvin: perhaps London, perhaps Philadelphia. There was a Ross M. Colvin living in the Philadelphia area until 1940, and perhaps that was him, but he was in the military in 1943, and stationed I-know-not-where. Just not enough information.

Harold W. Giles, the third Fortean considered here—him, I know where he lived. Buffalo New York. Indeed, he seems to have spent his entire life in upstate New York. Giles was born 1 July 1903 in Lockport Ward 3, Niagara, New York. His father was a laborer, variously captured by the census as a brass worker, a sweeper, and a caretaker. Chrestopher Giles was about 45 when Harold was born; his wife Elizabeth was twelve years his junior, and so the family kept growing for the next seven or eight years, Harold joined by three younger sisters. (He may have had older siblings who had already left the house, too.) He attended college in the mid-1920s—somewhere nearby, since he lived at home—and by 1930 was an insurance agent. Sometime between 1935 and 1938 he opened a bookstore, and it was as a bookseller that he made his living for the rest of his life. He died in Buffalo in 1983.

Giles was one of the most frequent, and long-acting, contributors to Doubt. He received at least 31 credits between 1943 and and 1958 (so issues 7-57, out of 61). He was a close reader of Fort, detecting that the omnibus edition (page 423) drops a line from New Lands (page 127). Thayer wrote, “Brother Giles is the mainspring of Forteanism in Buffalo, where he operates a bookstore in 67 West Chippewa Street.” By issue 12 (summer 1945), Thayer was giving Giles room to spread his wings and expanding his encomium. “The good Fortean not only gives us complete coverage of his local press (Buffalo) on quakes, volcanoes, propaganda and more abstruse Forteana, but he is alert for old books of Fortean significance, and for errors in the text of THE BOOKS, and in the pages of Doubt. More--he has made his bookstore at 67 West Chippewa Street, a center of Fortean interest and activity, always keeping a supply of THE BOOKS and of back numbers of the magazine on hand. The ‘second-hand bookstore’ is the logical gathering place for Forteans. If our ‘Religion of Self Respect’ has churches and temples, those are they. The brotherhood of the musty tome doffs its skull-cap to no ‘authority,’ not to Allibone, Dibdin or Book Prices Current, much less to Milliken, Compton and Shapley. When the Society has one Giles in every town of 50,000 and over, the world round, Your Secretary will lay down his crozier (with its runic inscription) and go Hellwards in full confidence of his reward—more data from Giles.”

That issue included a long column of material Giles contributed: about a priest struck by lightning, a blind man with a sick wife and child classed by the draft board as 1A; a bird that hit a plane in the dead of night; Draysoniana; an Italian exiled by Mussolini who refused to endorse the U.N.; comets that cannot be seen by amateur telescopes; Einstein admitting he was not a great mathematician: that is to say, all the Forteana Thayer liked, from anomalies to political and religious happenings.

Giles received another extended column in Doubt 28 (April 1950), in which he made winking predictions for the new year:

“M F S Giles took a gander at the future and decided to share the following with us:

I am aware that in making the following predictions of trends and events for 1950, I am acting contrary to the advise of a certain New York psychiatrist, who bids us live in the present, and (in surprising consonance with the 6th Chapt. St. Matthew) take no heed for the future. See a recent issue of TIME, wherefrom my intrepidity will appear all the more remarkable, inasmuch as the said psychiatrist is credited with several remarkable cures, (at $1,000. each); among them the curing of a fellow physician of the drug habit and an ex-cabin boy of homosexuality. Of course, it is easy to understand how a practicing physician could afford such expensive treatment, but certainly it isn’t every cabin boy (or ex-cabin boy either) who has a thousand dollars . . .

“But a fig for psychiatry! What have I to lose?

“I predict that during 1950:

“The stock-market will fluctuate, as the elder Morgan once predicted on another occasion.

“Prosperity will be general, but domestic finances are likely to be subject to a certain stringency, the more especially among those in the lower income brackets.

“The international situation is likely to become tense; but a marked tendency to the contrary is to be looked for if a sufficiently plausible publicity can be given to a threatened invasion of the earth by beings from another planet.

“The rich (with a few exceptions) will become wealthier; and, in consequence, the poor (with even fewer exceptions) will become poorer.

“The budget will, with a high degree of probability, remain thruout [sic] the calendar year, unbalanced.

“Science will make vast strides during 1950. And the people looking for adequate housing will cover a vast amount of territory, too.

“The number of people who will, in unpremeditated frenzy, commit suicide during the year is not expected to vary at all from the number giving [sic] the percentage of the population who made away with themselves in previous years.

“The condition of the arts will remain deplorable, since most of the artists (nowadays) appear to be as oblivious of direction as a whirling dervish.

“As for women’s styles, I venture to say that they will be becoming to some; and to others, only moderately so; or not at all.

“The Church will make gains in membership during the year, the more especially in the larger cities, where numbers tend to beget numbers; in the rural districts, a larger percentage will be likely to remain pagan.

“The State, in concert with its other self, The Church, will continue to foster the fiction that they are twain, essentially distinct, entities.

“Life Insurance Companies will enjoy a year of mixed blessings, Mortality will be low, (unless, of course, the war flares up with unexpected fury). Income from investments will be stable; but due to the general prosperity, fewer policy-holders will borrow from the companies at the customary high rates of interest; and hence, revenues may be low. However, more insurance will be written; and more capital come under the control of companies, who will, in consequence, become more influential than ever.

“The world population, despite war, disease, and a mounting toll of traffic accidents, will continue to increase; but not to any embarrassing extent as yet. No more than the usual number will starve; and flight to other planets will not become exigent; indeed, thee is not a little doubt that it may not even become feasible.

“Advertising will become more widespread and blatant than ever. And more money will be appropriated for education, tot he end that a larger percentage of the population will be able to read advertisements for themselves, as issued. What with radio, moving-pictures, and television, I cannot say that this trend will continue much beyond the present year. But for the immediate future it seems assured.

“On the other hand, that which is occult will, in all likelihood, remain hidden, unless perchance it should be revealed.

“As for the weather, the chances are that it will prove disappointing--all prognostications (except, of course, this one) notwithstanding.

“HAPPY NEW YEAR! H. W. Giles”

Again in June 1952 (number 37) he contributed a long piece, titled “Visits with the Professor. I. Physics as Bodies in Motion.” (Note there was never a II.) It recorded a mock conversation with a physicist who argued against the prevailing wisdom that most of matter was electrical (E=MC^2). The professor didn’t even believe in matter: everything was just bodies in motion. He went on for a while, arguing space and time were abstractions, that motion was the most basic fact—an abstruse set of reasonings. At the end, the physicist’s interlocutor—presumably Giles himself—remarked that Samuel Butler thought there was only one body: the universe itself. How did that square? The physicist would not be trapped: like Giles, he was a true Fortean. Giles quoted Butler, but the point about the universe being a single entity was just as surely Fort’s. And the physicist replied. “I never said that any of those bodies were real. I wouldn’t know what you meant by that. What is reality?” This was the Fortean bottom line; whatever the reasoning—and Giles’s was hard to follow—the conclusion was, reality is not what we think it is. Giles, then, was a thoughtful and playful Fortean—the two qualities usually went together—and it is a pity there is not more known about him.

We do know a lot about the fourth Fortean, Everett Franklin Bleiler. He too was playful and thoughtful, and showed some interest in Fort, though not so much the Fortean Society—and his interest does not seem to have been as intense as Giles’s. Bleiler was born 30 April 1920 in Boston Massachusetts to Joseph (37) and Rose (33) Bleiler. Joseph and Rose were natives of the state, both their sets of parents having emigrated from Germany. Joseph was a farmer. Bleiler attended Boston Latin and went to Harvard, concentrating his studies on anthropology. He enlisted in the army on 1 May 1942, his occupation at the time given as actor. He was 22.

Bleiler was an extensive reader. In a 2005 interview, he remembered, “From high school days on I used to buy books of all sorts that looked interesting and read them. Sometimes this paid off, sometimes it didn’t. While I had very little money, it was always possible to buy books cheaply. Americana was costly, but fantastic fiction was readily accessible at low prices.” In the same interview, Bleiler said that he had hoped to get into academia, but for whatever reason, that ambition went unfulfilled. Still, his life was a paean to intellectual work. In addition to the books on science fiction and fantasy he produced, Bleiler wrote introductions to the German and Japanese languages and did a number of translations. He also produced one archeological monograph.

Somewhere in all of his reading, Bleiler came across Fort and joined the Fortean Society in the early 1940s. He contributed at least one item—but Thayer ran out of space to get to it, and then never followed up. And he applied his intense scholarship to the field of science fiction and fantasy, creating one of the first bibliographies of the genre in 1948, an overview of some 500 texts written since 1800—a wide-ranging assortment, including works by the likes of Virginia Woolf. The science fiction publisher Shasta put out the book, and Thayer—then still on the science fiction bandwagon—raved, “Here is a field day for Forteans who, like Fort himself, delight in elaborating upon damned themes. The editor and chief compiler is MFS Bleiler, the publisher and prefacer is MFS Korshak, the dedicatee is MFS Shroyer, ‘all members of this club.’ The volume is THE CHECKLIST OF FANTASTIC LITERATURE, a Bibliography of Fantasy, Weird, and Science Fiction Books Published in the English Language, and if we were to match its “Listing by Author” against the Society’s rolls, we should certainly find upwards of twenty members represented ... YS is here, Russell and Abe Merritt--and Doreal and Derleth get editorial acknowledgement for assistance in the work. It was worth doing. It has been well done. Get your copy from the Society, bound in cloth, xvii and 455 pp. $6.00.”

By the early 1950s, though, Bleiler was losing interest in science fiction and fantasy writing. He took a job as an editor with Dover—admittedly overseeing the republication of some old fantasy, such as Robert W. Chambers’s stories—and slowly drifted from the field for the next quarter of a century. Exactly how interested he was in Fort during the 1940s is unclear from the record we have; but, at any rate, like a number of Forteans, he replaced whatever enthusiasm he had with other work.

Beginning int he 1970s, he returned to science fiction—and bibliography, eventually producing three annotated checklists of fantastic literature, providing later readers with pointers to literature that they might have missed as well as summaries of works that, by then, were almost impossible to obtain, particularly the stories published in pulp magazines of the mid-century. (He also contributed to other bibliographic projects, particularly relating to crime stories.) The books were The Guide to Supernatural Fiction: A Full Description of 1,775 Books from 1750 to 1960, Including Ghost Stories, Weird Fiction, Stories of Supernatural Horror, Fantasy, Gothic Novels, Occult Fiction, and Similar Literature, with Author, Title and Motif Indexes (1983); Science Fiction: The Early Years: A Full Description of More Than 3,000 Science-Fiction Stories from Earliest Times to the Appearance of the Genre Magazines in 1930 with Author, Title, and Motif Indexes (1991); and Science-Fiction: The Gernsback Years: A Complete Coverage of the Genre Magazines Amazing, Astounding, Wonder, and Others from 1926 Through 1936 (1998). The last two were compiled with the help of his son, Richard.

These compendium helped to highlight and sustain interest in Fort. Bleiler pointed out what he thought were Fortean influences in various stories—and included these in the index, allowing for the later reader to get some sense of the breadth of Fort’s influence on science fiction in the middle part of the twentieth century. They also included Bleiler’s mature thoughts on Fort. In the 1970s, tyne science fiction fan—and Fortean critic—Sam Moskowitz had republished Fort’s 1906 story “A Radicle Corpuscle,” which late out in the terms of fantastic fiction Fort’s monism. Bleiler included a summary of this story—“an amusing sketch”—in his second compilation, with an added plug: “Apart from Fort’s ‘serious’ work, which is often brilliantly stated and fascinating, though certainly not acceptable, his novel The Outcast Manufacturers (1909) is worth reading,” as was Moskowitz’s essay on Fort’s short stories, which were otherwise unknown.

Later in the tome, in a section on background material, Bleiler deals with Fort’s non-fiction, under the heading Book of the Damned:

“An eccentric philosopher-historian, Fort devoted his light to collecting and collating information about odd manifestations that he insisted had been ignored by orthodox science, yet deserved attention in suggesting new, better formulations. He described his data as ‘damned,’ i.e., consciously and systematically excluded from discussion, suppressed because they do not fit established orthodoxy. In a series of four books--The Book of the Damned (1919), New Lands (1923), Lo (1931); sic; Wild Talents (1932),—Fort coordinated a vast amount of ‘rubbish of science’ that has served as a data bank for writers, for cranks, and charlatans. The flying saucer proponents, for example, draw heavily on Fort’s work. Although Fort often concealed his theoretical position in deliberately outrageous conclusions, he was essentially a belated philosophical idealist, a monist who held that manifestations are reversible to oneness, and that phenomenality is half-way between existence and non-existence, being the result of a driver toward individuation. Like the early nineteenth-century idealists he held that the act of recognizing self immediately created a non-self, and thereby host of relationships. On a more material level, he seems to have held that the universe is a ‘living’ self-adjusting mechanism with as yet unrecognized parallelisms and interchanging mechanisms running through it. Thus, earth and the individual are not isolated entities, but members of complexes affected by currents from larger or other entities. His data are intended to be proofs of such relationships. In the present volume [Book of the Damned] Fort concerns himself mostly with strange objects that purportedly have fallen from the sky: rains of fish and other marine life; falls of frogs; odd cloth-like substances, unusual meteorites; appearances in the heavens, like luminous flying objects; thunderstones; artifacts found in circumstances of great geological age; underwater lights; astronomical viewings not generally accepted; and astronomical fiascos. Most of his data are derived from nineteenth century journals and newspapers, which, although collated whimsically, are cited precisely. The obvious irony, of course, is that Fort, who distrusted almost anything stated by an academic, had an enormous faith in the amateur printed word—though he himself was a newspaperman! Fort became a source of ideas in science-fiction in the 1920s and 1930s. The term ‘Fortean’ was later applied to such work. Writers on the whole ignored his philosophical ideas, but found his fact chains useful.”

Everett Franklin Bleiler died in 2010.