A colorful Fortean, sensu stricto.

Faber Bernard Birren was born 21 September 1900 in Chicago to Joseph Pierre Birren and Crescentia Lang. He was the third of three children, with an elder sister and brother. His father, Joseph, was an artist, and obviously instilled some of that in Faber, starting with his name, which translates as craftsman. (His sister was Jeanette, his bother William.) The family was doing well enough in 1910 to also board a servant. Birren painted from an early age, including murals around the family home. He attended Mount Carmel Roman Catholic Elementary School before moving to Nichols Senn High School, where he studied art and ceramics while also taking courses at the Art Institute of Chicago his final two years, where he studied painting and drawing. His mother was a skilled pianist.

William was old enough to register for the draft during the Great War—he was living in Buffalo at the time—but apparently Faber just missed out; at least, there’s no draft card for him. He matriculated at the University of Chicago in 1919, where he initially planned to study education, but he was already being drawn to color theory. He pledged the fraternity Delate Sigma Phi and contributed art to the yearbook. At the time, he was living with his sister and her husband. He stayed at the University for only two years, and in 1921 went to work at the bookseller Charles T. Powner. Likely, he met Tiffany Thayer while at this job: several years younger, Thayer had left him early and was employed by Powner during this same period. While working in the business, Birren began collecting books on color, devising his own course of study in the subject. He talked with psychologists, physicists, and ophthalmologists and conducted experiments, such as painting his room vermillion to see if it would drive him mad.

Faber Bernard Birren was born 21 September 1900 in Chicago to Joseph Pierre Birren and Crescentia Lang. He was the third of three children, with an elder sister and brother. His father, Joseph, was an artist, and obviously instilled some of that in Faber, starting with his name, which translates as craftsman. (His sister was Jeanette, his bother William.) The family was doing well enough in 1910 to also board a servant. Birren painted from an early age, including murals around the family home. He attended Mount Carmel Roman Catholic Elementary School before moving to Nichols Senn High School, where he studied art and ceramics while also taking courses at the Art Institute of Chicago his final two years, where he studied painting and drawing. His mother was a skilled pianist.

William was old enough to register for the draft during the Great War—he was living in Buffalo at the time—but apparently Faber just missed out; at least, there’s no draft card for him. He matriculated at the University of Chicago in 1919, where he initially planned to study education, but he was already being drawn to color theory. He pledged the fraternity Delate Sigma Phi and contributed art to the yearbook. At the time, he was living with his sister and her husband. He stayed at the University for only two years, and in 1921 went to work at the bookseller Charles T. Powner. Likely, he met Tiffany Thayer while at this job: several years younger, Thayer had left him early and was employed by Powner during this same period. While working in the business, Birren began collecting books on color, devising his own course of study in the subject. He talked with psychologists, physicists, and ophthalmologists and conducted experiments, such as painting his room vermillion to see if it would drive him mad.

Birren first published on color in 1924 and tried to get a book out on the subject, too, but Color in Vision would have to wait four years to see the light of the day. That was apparently, also, the year he started working for himself. Although he would write voluminously throughout his life, papers and monographs and popular expositions and novels, at first the life of a freelancer was not remunerative enough. In 1933, he moved to New York and switched his focus from being purely a writer to being a consultant. One of his first jobs was to have billiard table tops changed so that they were no longer associated with grotty billiard parlors, thus making them available to be purchased for home use. After that, he was employed by a number of industries, advising companies to change wall color to reduce eye fatigue or paint machinery bright colors for safety reasons. If he did not meet Thayer while at Powner’s, it was here, in New York City, that the two would have met, what with Birren advising industries and Thayer doing advertising.

According to the 1930 census, Birren married someone by the name of Gladys, from Iowa, around 1927. Nothing is known of her. In 1934 or 1935—accounts differ—he married Wanda Martin. They would have two children, Zoe Birren (22 September 1935) and Fay (1 May 1939). There is some confusion here, as Faber should have been in New York at the time of Zoe’s birth, but her certificate is from Cook County, Illinois. Wanda was supportive of her husband’s work. During this decade, in addition to his consulting work, Birren published four books, The Printer’s Art of Color (1934), Functional Color (1937), The Wonderful Wonders of Red-Yellow-Blue (1937), Color in Modern Packaging (1938), with a fifth coming out in 1941—The Story of Color. It was in these works that Birren developed his theory of colors, based on the work of the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. (Ironically, Chevreul was skeptical of spiritualism, dowsing, and other forms of alternate science.) Chevreul was interested in color harmony, and through him Birren also found inspiration in the great German polymath Goethe. Goethe had a very developed color theory, on that challenged Newton’s ideas in some ways. But what’s important in regards to Birren is that attention was on the perception of color more than the physics.

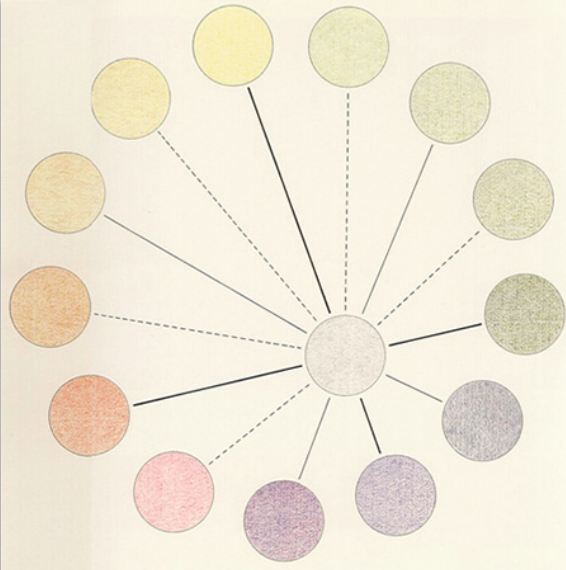

In 1934, Birren introduced his “rational color circle.” Edith Anderson Feisner explains, Birren “arranged hues in equal intervals but tended to include more warm than cool hues in its make-up, so that the natural gray ‘center’ was asymmetrically placed. His rationale for this was that the eye sees more warm hues than cool ones. Although he retained the premise that red, yellow, and blue were primaries, within the warm area of his week he added a leaf green and within the cool area a turquoise Red and green were complementary, and could function was either warm or cool.”

According to the 1930 census, Birren married someone by the name of Gladys, from Iowa, around 1927. Nothing is known of her. In 1934 or 1935—accounts differ—he married Wanda Martin. They would have two children, Zoe Birren (22 September 1935) and Fay (1 May 1939). There is some confusion here, as Faber should have been in New York at the time of Zoe’s birth, but her certificate is from Cook County, Illinois. Wanda was supportive of her husband’s work. During this decade, in addition to his consulting work, Birren published four books, The Printer’s Art of Color (1934), Functional Color (1937), The Wonderful Wonders of Red-Yellow-Blue (1937), Color in Modern Packaging (1938), with a fifth coming out in 1941—The Story of Color. It was in these works that Birren developed his theory of colors, based on the work of the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. (Ironically, Chevreul was skeptical of spiritualism, dowsing, and other forms of alternate science.) Chevreul was interested in color harmony, and through him Birren also found inspiration in the great German polymath Goethe. Goethe had a very developed color theory, on that challenged Newton’s ideas in some ways. But what’s important in regards to Birren is that attention was on the perception of color more than the physics.

In 1934, Birren introduced his “rational color circle.” Edith Anderson Feisner explains, Birren “arranged hues in equal intervals but tended to include more warm than cool hues in its make-up, so that the natural gray ‘center’ was asymmetrically placed. His rationale for this was that the eye sees more warm hues than cool ones. Although he retained the premise that red, yellow, and blue were primaries, within the warm area of his week he added a leaf green and within the cool area a turquoise Red and green were complementary, and could function was either warm or cool.”

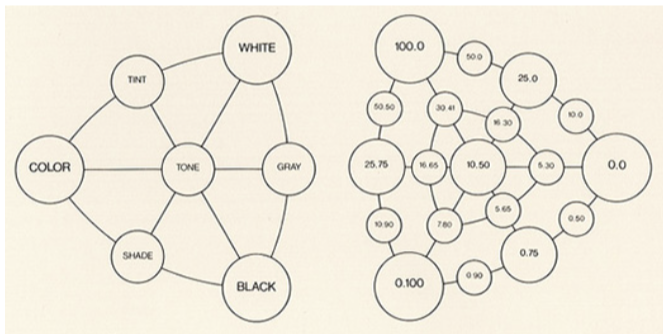

Three years later, as part of his continued investigation, he introduced a color triangle, which defined shades and tints. Feistier again: “This triangle dealt with the visual and psychological aspects of any color. He stated that there are pure colors or hues, white, and black. These three elements at the points of the triangle can be combined so that white added to a color gives a tint, black added to a color gives a shade, and black added to white gives a gray. They were placed intermittently on the triangle. The center of the diagram showed tone, that is, a combination of the three elements of black, white, and color. Using his ‘harmony of color forms,’ which Birren felt charted color effects, unlike the color schemes used until this time, he evolved what he termed the ‘new perception’ of color.” These included the effects of luster, iridescence, luminosity, transparency, and chromatic light.

World War II and the subsequent explosion of home goods helped to make Birren very successful. With the DuPont company, he worked out a master color safety code for industry, which was also adopted by the military and credited with reducing accidents among service members from 46 per thousand to 5.5. He also worked with the navy to color coordinate all its possessions, every single item and structure and piece of clothes. In subsequent years, he would consult with G.E. and Walt Disney and a host of industries providing homes with a proliferation of new products, phones and refrigerators and all the rest. In 1949, he moved to Stamford, Connecticut, but kept his office in New York City.

Birren remained a prolific author and lecturer, publishing over 250 articles and forty books by the time of his death. In the 1950s, he experimented with fiction, the first two under pseudonyms. As early as the 1940s, Birren was publishing some of his work on color under the pseudonym Martin Lang (Character Analysis through Color), and he would occasionally use that name over the years. He adapted it for his fiction, too, keeping the surname—his mother’s maiden name—and adding the first name Gregor. The two books he put out as Gregor Lang were Terra: An Allegory (1953) and The Unconsidered (1955). (There may be a third: The Unconsidered lists in the front matter books by the same author and includes, also, the title The Tories. I have otherwise found no trace of this book.) In 1958, under his own name, he put out Make Mine Love.

Terra presents itself as a series of connected vignettes written by the author’s great grandfather, Henry Lang, who was raised in Luxembourg during the tumultuous nineteenth-century when that country came under the rule of one country after another—all the disruption supposedly driving Henry to Buffalo, New York, where he penned these stories in Moselfrankisch, which Gregor then had translated. They tell an alternate history of a group called The Midianites, who have a chance to join with Moses and become part of God’s chosen people, and later to accept the teaching of Christ, but resist (for the most part) choosing, instead, to stubbornly measure themselves by the standards of humanity, rejecting romantic variants of Nietzscheanism for a more humble dedication to work. Stories are told within stories, allegories whose meaning is hidden only by the easily deciphered code of giving a character the name of a virtue written backwards—so that Layol becomes a hero, and Reldi a villain. For all that the book threatens to become overly didactic, Birren makes it involving by never forgetting that his characters are characters first and adding little grace notes that make the story come feel true. The point is not to imagine a perfect utopia, but instead pose the struggles of the Midianites as a model for humans: that their focus should be on work and helping one another; that religion leads to extremism and hierarchy; that even with everyone working hard, humans will be consumed by passions at times, and make mistakes, and go to war, and all the rest: the best we can hope is to temper those tendencies and get back on track when civilization’s run off the rails. It’s an interesting and unexpected book, one that suggests Birren, fulfilled by his work on color, had more he wanted to say.

The Unconsidered is also a series of interconnected vignettes, a kind of Spoon River Anthology of a Connecticut town around 1900, once more expressing Birren’s vaguely leftist sympathies (alloyed with a realist’s sense that the rich and powerful will always exploit others.) Most of the action revolves around the aristocratic English Lear family that owns the town's business, a luggage making factory that employs the Polish immigrants that make up the bulk of the community. The story touches on labor unrest--the Poles are threatening a strike--and the chicanery of the Lear paterfamilias, in scapegoating a Polish worker for his company's own negligence. There is also Lear's amoral lawyer, who eventually inherits the Lear business. Also turning up in the story are Lear's son, Sundy, a labor agitator who joins the leader of the Polish community in the Spanish American War--his voice comes through mostly in letters he writes to the town Doctor--Dr. Blucher, a doctor of limited skills who opens his home to a worker made legless by an industrial accident and his daughter, who falls in love with Lear's nephew. Blucher spends a great deal of his tie tending to Lear's daughter, who suffers from an unspecific ailment.

There is nostalgia, here: the author admits in a preface that he grew up in a similar town, and he uses illustrations throughout the book--and portraits of the main character--because he remembers being impressed by picture books of the time. But it is tinged with a naturalism of the Dreiser school. Sundy's a womanizer, and Blucher has had to perform abortions on his lovers. The sister, Charlotte, was similarly a bedhopper, and, we learn at the end--spoiler alert, yeah, but the book's over fifty years old!--that she castrated herself to stop the urges. (There is also talk of a hermaphrodite.) Probably this material was more scandalous at the time than it is now, and here it is certainly presented circumspectly. Nicely, though, as important as these issues are to the book, the salacious details never overwhelm the story. The characters are still otherwise vivid. And in the middle of the story, Lange hits his stride, the language mostly sharp, the narrative with some drive. It could have been a fine novel.

The real problem is given away by the title--The Unconsidered. Birren's sympathies are against the Lear's and their curdled aristocracy. Like a good nineteenth century novel, it ends with a marriage that is supposed to resolve and negate the tensions of the previous generation, the wholly good working class girl marrying William, who foreswears his heritage. We are supposed to are about the Poles, and the way they are screwed over, first by Lear, and later by his lawyer, who closes the factory. But we hardly ever see the Poles, and mostly when we do it is through the lens of other characters--mostly protagonists, but still, we don't really get a view of their life, their social systems. For all the empathy Birren has toward the Poles and others excluded from the American Dream, they are as unconsidered in this book as they were at the time.

Make Mine Love is a striking departure from these earlier two novels, focused on a single narrative, written in a pulpier tradition—one could see Thayer writing something like this in the thirties—a silly Madame Bovary for the 1950s, just before the sexual revolution: libidinous sex as a wrecking ball knocking down stale mores, but simultaneously a fundamentally ridiculous act. As the back cover notes, Birren lived in the suburbia he describes here, and seems to have been very disgusted with it. The book tries for insight and satire, I think, but usually falls into extreme melodrama and pedantic hand-wringing. There's little of the realism of his earlier novel, even if that realism had been touched with nineteenth-century Romanticism.

The story revolves around the lives of three bored suburban wives, all sketched very simply: the superficial Marcia, the alcoholic Jackie, and the do-gooder Dale, each married to some important, rich man who flits into and out of the story as necessary. The story takes off--and its title--when Marcia tells the ridiculously handsome bartender her order: "Make Mine Love." Thus follows a circumspect but still extremely embarrassingly written sex scene. (Later we learn that Joe, the bartender, brings Marcie to orgasm three times, then tells her, it was her turn to service him.) Joe, it turns out, has many lovers, which sends Marcia around the bend--and she starts sleeping with other men. All the while, her distant husband figures she's stepping out on him, but he's got the wrong man and makes a fool of himself in the process. Meanwhile, Jackie tries to seduce Joe, but is continually shot down because she's a drunk--all of that not a surprise to her unflappable husband. Meanwhile, Dale, much to her own surprise, also falls in with Joe. Her husband finds out, and sets out for revenge and divorce.

All of this melodrama is interwoven with a ridiculous plot about the mob: Joe works for the mob and his club is its extension into the quiet suburb. Dale's husband employs Jackie's to shut it down, and gets beat up. Joe gets beat up. Even a minister's wife gets beaten up before the mob is finally driven out of town and down to Florida, where the book ends with Marcia unexpectedly meeting Joe and narrating his final fall from grace.

The structure of the story might suggest more lecturing on the dangers of swarthy types in rich neighborhoods, but, to his credit, Birren never makes any of that explicit--although Joe is certainly the very ideal of the lusty Latin lover. More problematic is that much--although not all--of the tale is told from the perspective of women and Birren's grasp of female psychology was, let's say, limited: Dale was too disgusted by sex to be believable as a mother of four. Marcia's musing that a man might give only part of himself during sex, but a woman must invest her whole self, comes across more as male wishful thinking. Just as Joe is too much an example of how women secretly desire truly virile men, and an accusation against the limps of suburbia. At times, too, Birren seems to want to shock for the sake of shocking, as when he lists the various debaucheries offered in New York; gay clubs, porn theaters, gambling halls, whorehouses, and sex shows. But there is a point he is trying to make--that the conventions of the day, the mores and religious admonitions, no longer fit with modern society. When one of the character says that what the world needs is a new religious leader, he seems to be speaking for Birren himself. The energy of sex has revealed the emptiness of Victorian notions--even if sex itself is so often ridiculous (purposefully portrayed here that way, as well as inadvertently).

To his credit, though, even as he cannot quite get the female characters correct, he does give them a great deal of agency and autonomy (they pass the Bechdel test), which was also true in his pseudonymous book The Unconsidered, with the daughter's health issues kept secret from her father, even when he demanded to know about it. Marcia, Jackie, and Dale may be thinly drawn stereotypes, but they are not controlled by their husbands, nor do their world's revolve around the husbands--and Birren gives us no reason to think that this is the problem with the social world he has drawn. It is not lack of proper family structure that is the problem, but the lack of meaning. One of the characters makes passing reference to French existentialism--dismissively--but one wonders if Birren isn't afraid that the existentialists are right, that, without the proper mores to fit the era, Americans in the 1950's suburbs have lost all drive, all ambition, beyond making money, drinking, and having sex. And that would seem to be the hidden, other meaning of the book's title. That there is no love anymore, just shallow materialism.

In the 1960s, Birren started a new project, reprinting historically important works on color and color theory. First, in 1963, came republication of Mose Harris’s The Natural System of Colours (1766), with Birren adding annotation and notes. Chevreul’s book came out in 1967. And there were others, too. Intriguingly, these found fans among Forteans, or at least Fortean allies. Brian’s republication of Edwin D. Babbit’s The Principles of Light and Color was warmly reviewed in the Journal of Borderland Research (successor to N. Meade Layne’s Round Robin), since Babbitt was something of an occultist. Indeed, Birren had published on the occult meanings of color as early as 1941—Story of Color—From Ancient Mysticism to Modern Science—and he was a firm believer in the therapeutic value of colors: bright colors, he said, particularly cerise, could calm the mentally troubled by taking their focus away from themselves. This line of thought overlapped with color-healing, an alternative medicine that was of interest to some Forteans and their associates.

By the 1970s, Birren was slowing down somewhat. He donated his papers and many of his books to Yale University Library—that center of Fortean scholarship!—and endowed a fund for research and publication on color. A member of a number of art committees, he also established awards for and funds for annual shows. In Stamford, he was a member of the Unitarian Universalist Society. Another member of the Society, Warren Allen Smith, was book review editor for The Humanist, and had assigned Terra to be reviewed by Mary Stone Morain. This link is another connection to Forteana, as int he 1950s, Thayer was associating the Society (and Forteanism) with humanism and other forms of organized skepticism—an alliance that would not last, for as skepticism developed it became a foe of Forteanism.

Faber Birren died 30 December 1988, after suffering a stroke.

The outlines of Birren’s Forteanism is visible in the biography: and if there’s much substance to it, I haven’t really found it. Given that he wrote so much—and I have not combed through much of it at all—it is entirely possible that Birren mentioned Fort somewhere, but I have not seen it. As to his activities within the Fortean Society—they are scanty. His primary role seems to have been “friend of Tiffany.” And even that could be arduous.

Birren was one of the earliest members of the Fortean Society, receiving the number 22, which places him as joining just after the Founders. His name was never mentioned in the early publicity, which may just reflect that he was not very well known in 1931, or it ma suggest that he joined after the initial founding and party. Thayer started reconstituting the Society in 1935, and he may have approached Birren then—either as an old friend from Chicago who had also found his way to New York, or as a new friend from New York. That Birren joined indicates he had some interest in Fort, at least enough to be associated with what would become a somewhat notorious organization, or it just may be that he was a good enough friend with Thayer that he wanted to support him. He did receive the issues of Doubt and held onto them for a while, but by 1968 Birren admitted to having lost them somewhere over the years.

The Society also supported Birren, advertising his books on color as early as 1944. “This is by all odds the finest book on color in print,” Thayer wrote about The Story of Color in one of the Society’s bookselling pamphlets. And he had some experience with color, since painting was one of Thayer’s hobbies. Thayer also used Birren as a resource when questions about color came up—even though Birren accepted the conventional color spectrum—which they did in the context of color healing often enough.

First mention of Birren in the Society’s magazine proper came in Doubt 14 (Spring 1946)—twice, although both were tangential references. On page 204, Thayer complained that the government had won a jury trial against Dinshah P. Ghadiali forcing him to stop selling his ‘spectrochrome’ machines, which produced a colored light that were supposed to make people feel better. “The use of colored lights in healing is no new thing,” Thayer wrote. “One recalls that Babbit advocated use of yellow light for a physic. Our MFS Faber Birren will cite you books on the subject for the past two or three centuries. MFS George Starr White M.D., has had wide experience in the field.” Thayer went on to note that there were others selling color healing kits, including The Auratone Foundation of America, which was supported by Bing Crosby, and to reminisce about the “Art Institute of Light, which had a color organ, that was an esoteric fad in the 1920s. The other mention was the result of another Fortean challenging Birren. Marie P. Sweet (who has already been considered) accused Birren of giving insufficient credit to Wilhelm Ostwald. Thayer looked into the matter and disagreed, but still published Sweet’s own thoughts on color.

It wasn’t for another two years that Birren would appear in Doubt, again tangentially. Doubt 24 (April 1949) had a squib titled “No Wonder,” written by Thayer: “In a story about which ‘American’ books the Nippiness are now permitted to publish, Walter Simmons wrote to the Chicago Tribune from Tokyo, May 20, 1948, old style, stating that—‘The Japanese are puzzled by such titles as Selling With, by Faber Birren.’ One finds little to wonder at in that. The book is Selling with Color, by MFS Birren.”

Four years later, and Birren’s name made its last appearance in Doubt, this one an acknowledged tangent, but more substantive than any of the others. In Doubt 42 (October 1953), Thayer catalogued books suggested by a new member, J. T. Boulton. Among them was Ernest Lehrs Man or Matter which Thayer glossed as “an understanding of Nature on the basis of Goethe’s Method of training observation and thought.” It included a “vigorous attack on Newtonian optics in particular.” After rehearsing some more of the contents, Thayer noted “Incidentally, our own color man—Faber Birren—is very cordial to Goethe’s optics.”

All of which leaves very little Forteanism on Birren’s part. What seems more important is his friendship with Thayer. Damon Knight—the science fiction writer—contacted him in 1968 when he was compiling information for a biography of Fort. Brian was one of the few to know that Thayer had donated material to the New York Public Library (these were mostly Fort’s notes) and also offered Knight some biographical information on Thayer, including the fact that he wrote his manuscripts by hand (the bulk of the remaining material he donated to the NYPL were handwritten drafts of Mona Lisa.) But Birren noted that Thayer put strains on their friendship. Although they had known each other for a long time, he said he could not stand to be in Thayer’s company for very long—he was too contentious, too rude.

Birren remained a prolific author and lecturer, publishing over 250 articles and forty books by the time of his death. In the 1950s, he experimented with fiction, the first two under pseudonyms. As early as the 1940s, Birren was publishing some of his work on color under the pseudonym Martin Lang (Character Analysis through Color), and he would occasionally use that name over the years. He adapted it for his fiction, too, keeping the surname—his mother’s maiden name—and adding the first name Gregor. The two books he put out as Gregor Lang were Terra: An Allegory (1953) and The Unconsidered (1955). (There may be a third: The Unconsidered lists in the front matter books by the same author and includes, also, the title The Tories. I have otherwise found no trace of this book.) In 1958, under his own name, he put out Make Mine Love.

Terra presents itself as a series of connected vignettes written by the author’s great grandfather, Henry Lang, who was raised in Luxembourg during the tumultuous nineteenth-century when that country came under the rule of one country after another—all the disruption supposedly driving Henry to Buffalo, New York, where he penned these stories in Moselfrankisch, which Gregor then had translated. They tell an alternate history of a group called The Midianites, who have a chance to join with Moses and become part of God’s chosen people, and later to accept the teaching of Christ, but resist (for the most part) choosing, instead, to stubbornly measure themselves by the standards of humanity, rejecting romantic variants of Nietzscheanism for a more humble dedication to work. Stories are told within stories, allegories whose meaning is hidden only by the easily deciphered code of giving a character the name of a virtue written backwards—so that Layol becomes a hero, and Reldi a villain. For all that the book threatens to become overly didactic, Birren makes it involving by never forgetting that his characters are characters first and adding little grace notes that make the story come feel true. The point is not to imagine a perfect utopia, but instead pose the struggles of the Midianites as a model for humans: that their focus should be on work and helping one another; that religion leads to extremism and hierarchy; that even with everyone working hard, humans will be consumed by passions at times, and make mistakes, and go to war, and all the rest: the best we can hope is to temper those tendencies and get back on track when civilization’s run off the rails. It’s an interesting and unexpected book, one that suggests Birren, fulfilled by his work on color, had more he wanted to say.

The Unconsidered is also a series of interconnected vignettes, a kind of Spoon River Anthology of a Connecticut town around 1900, once more expressing Birren’s vaguely leftist sympathies (alloyed with a realist’s sense that the rich and powerful will always exploit others.) Most of the action revolves around the aristocratic English Lear family that owns the town's business, a luggage making factory that employs the Polish immigrants that make up the bulk of the community. The story touches on labor unrest--the Poles are threatening a strike--and the chicanery of the Lear paterfamilias, in scapegoating a Polish worker for his company's own negligence. There is also Lear's amoral lawyer, who eventually inherits the Lear business. Also turning up in the story are Lear's son, Sundy, a labor agitator who joins the leader of the Polish community in the Spanish American War--his voice comes through mostly in letters he writes to the town Doctor--Dr. Blucher, a doctor of limited skills who opens his home to a worker made legless by an industrial accident and his daughter, who falls in love with Lear's nephew. Blucher spends a great deal of his tie tending to Lear's daughter, who suffers from an unspecific ailment.

There is nostalgia, here: the author admits in a preface that he grew up in a similar town, and he uses illustrations throughout the book--and portraits of the main character--because he remembers being impressed by picture books of the time. But it is tinged with a naturalism of the Dreiser school. Sundy's a womanizer, and Blucher has had to perform abortions on his lovers. The sister, Charlotte, was similarly a bedhopper, and, we learn at the end--spoiler alert, yeah, but the book's over fifty years old!--that she castrated herself to stop the urges. (There is also talk of a hermaphrodite.) Probably this material was more scandalous at the time than it is now, and here it is certainly presented circumspectly. Nicely, though, as important as these issues are to the book, the salacious details never overwhelm the story. The characters are still otherwise vivid. And in the middle of the story, Lange hits his stride, the language mostly sharp, the narrative with some drive. It could have been a fine novel.

The real problem is given away by the title--The Unconsidered. Birren's sympathies are against the Lear's and their curdled aristocracy. Like a good nineteenth century novel, it ends with a marriage that is supposed to resolve and negate the tensions of the previous generation, the wholly good working class girl marrying William, who foreswears his heritage. We are supposed to are about the Poles, and the way they are screwed over, first by Lear, and later by his lawyer, who closes the factory. But we hardly ever see the Poles, and mostly when we do it is through the lens of other characters--mostly protagonists, but still, we don't really get a view of their life, their social systems. For all the empathy Birren has toward the Poles and others excluded from the American Dream, they are as unconsidered in this book as they were at the time.

Make Mine Love is a striking departure from these earlier two novels, focused on a single narrative, written in a pulpier tradition—one could see Thayer writing something like this in the thirties—a silly Madame Bovary for the 1950s, just before the sexual revolution: libidinous sex as a wrecking ball knocking down stale mores, but simultaneously a fundamentally ridiculous act. As the back cover notes, Birren lived in the suburbia he describes here, and seems to have been very disgusted with it. The book tries for insight and satire, I think, but usually falls into extreme melodrama and pedantic hand-wringing. There's little of the realism of his earlier novel, even if that realism had been touched with nineteenth-century Romanticism.

The story revolves around the lives of three bored suburban wives, all sketched very simply: the superficial Marcia, the alcoholic Jackie, and the do-gooder Dale, each married to some important, rich man who flits into and out of the story as necessary. The story takes off--and its title--when Marcia tells the ridiculously handsome bartender her order: "Make Mine Love." Thus follows a circumspect but still extremely embarrassingly written sex scene. (Later we learn that Joe, the bartender, brings Marcie to orgasm three times, then tells her, it was her turn to service him.) Joe, it turns out, has many lovers, which sends Marcia around the bend--and she starts sleeping with other men. All the while, her distant husband figures she's stepping out on him, but he's got the wrong man and makes a fool of himself in the process. Meanwhile, Jackie tries to seduce Joe, but is continually shot down because she's a drunk--all of that not a surprise to her unflappable husband. Meanwhile, Dale, much to her own surprise, also falls in with Joe. Her husband finds out, and sets out for revenge and divorce.

All of this melodrama is interwoven with a ridiculous plot about the mob: Joe works for the mob and his club is its extension into the quiet suburb. Dale's husband employs Jackie's to shut it down, and gets beat up. Joe gets beat up. Even a minister's wife gets beaten up before the mob is finally driven out of town and down to Florida, where the book ends with Marcia unexpectedly meeting Joe and narrating his final fall from grace.

The structure of the story might suggest more lecturing on the dangers of swarthy types in rich neighborhoods, but, to his credit, Birren never makes any of that explicit--although Joe is certainly the very ideal of the lusty Latin lover. More problematic is that much--although not all--of the tale is told from the perspective of women and Birren's grasp of female psychology was, let's say, limited: Dale was too disgusted by sex to be believable as a mother of four. Marcia's musing that a man might give only part of himself during sex, but a woman must invest her whole self, comes across more as male wishful thinking. Just as Joe is too much an example of how women secretly desire truly virile men, and an accusation against the limps of suburbia. At times, too, Birren seems to want to shock for the sake of shocking, as when he lists the various debaucheries offered in New York; gay clubs, porn theaters, gambling halls, whorehouses, and sex shows. But there is a point he is trying to make--that the conventions of the day, the mores and religious admonitions, no longer fit with modern society. When one of the character says that what the world needs is a new religious leader, he seems to be speaking for Birren himself. The energy of sex has revealed the emptiness of Victorian notions--even if sex itself is so often ridiculous (purposefully portrayed here that way, as well as inadvertently).

To his credit, though, even as he cannot quite get the female characters correct, he does give them a great deal of agency and autonomy (they pass the Bechdel test), which was also true in his pseudonymous book The Unconsidered, with the daughter's health issues kept secret from her father, even when he demanded to know about it. Marcia, Jackie, and Dale may be thinly drawn stereotypes, but they are not controlled by their husbands, nor do their world's revolve around the husbands--and Birren gives us no reason to think that this is the problem with the social world he has drawn. It is not lack of proper family structure that is the problem, but the lack of meaning. One of the characters makes passing reference to French existentialism--dismissively--but one wonders if Birren isn't afraid that the existentialists are right, that, without the proper mores to fit the era, Americans in the 1950's suburbs have lost all drive, all ambition, beyond making money, drinking, and having sex. And that would seem to be the hidden, other meaning of the book's title. That there is no love anymore, just shallow materialism.

In the 1960s, Birren started a new project, reprinting historically important works on color and color theory. First, in 1963, came republication of Mose Harris’s The Natural System of Colours (1766), with Birren adding annotation and notes. Chevreul’s book came out in 1967. And there were others, too. Intriguingly, these found fans among Forteans, or at least Fortean allies. Brian’s republication of Edwin D. Babbit’s The Principles of Light and Color was warmly reviewed in the Journal of Borderland Research (successor to N. Meade Layne’s Round Robin), since Babbitt was something of an occultist. Indeed, Birren had published on the occult meanings of color as early as 1941—Story of Color—From Ancient Mysticism to Modern Science—and he was a firm believer in the therapeutic value of colors: bright colors, he said, particularly cerise, could calm the mentally troubled by taking their focus away from themselves. This line of thought overlapped with color-healing, an alternative medicine that was of interest to some Forteans and their associates.

By the 1970s, Birren was slowing down somewhat. He donated his papers and many of his books to Yale University Library—that center of Fortean scholarship!—and endowed a fund for research and publication on color. A member of a number of art committees, he also established awards for and funds for annual shows. In Stamford, he was a member of the Unitarian Universalist Society. Another member of the Society, Warren Allen Smith, was book review editor for The Humanist, and had assigned Terra to be reviewed by Mary Stone Morain. This link is another connection to Forteana, as int he 1950s, Thayer was associating the Society (and Forteanism) with humanism and other forms of organized skepticism—an alliance that would not last, for as skepticism developed it became a foe of Forteanism.

Faber Birren died 30 December 1988, after suffering a stroke.

The outlines of Birren’s Forteanism is visible in the biography: and if there’s much substance to it, I haven’t really found it. Given that he wrote so much—and I have not combed through much of it at all—it is entirely possible that Birren mentioned Fort somewhere, but I have not seen it. As to his activities within the Fortean Society—they are scanty. His primary role seems to have been “friend of Tiffany.” And even that could be arduous.

Birren was one of the earliest members of the Fortean Society, receiving the number 22, which places him as joining just after the Founders. His name was never mentioned in the early publicity, which may just reflect that he was not very well known in 1931, or it ma suggest that he joined after the initial founding and party. Thayer started reconstituting the Society in 1935, and he may have approached Birren then—either as an old friend from Chicago who had also found his way to New York, or as a new friend from New York. That Birren joined indicates he had some interest in Fort, at least enough to be associated with what would become a somewhat notorious organization, or it just may be that he was a good enough friend with Thayer that he wanted to support him. He did receive the issues of Doubt and held onto them for a while, but by 1968 Birren admitted to having lost them somewhere over the years.

The Society also supported Birren, advertising his books on color as early as 1944. “This is by all odds the finest book on color in print,” Thayer wrote about The Story of Color in one of the Society’s bookselling pamphlets. And he had some experience with color, since painting was one of Thayer’s hobbies. Thayer also used Birren as a resource when questions about color came up—even though Birren accepted the conventional color spectrum—which they did in the context of color healing often enough.

First mention of Birren in the Society’s magazine proper came in Doubt 14 (Spring 1946)—twice, although both were tangential references. On page 204, Thayer complained that the government had won a jury trial against Dinshah P. Ghadiali forcing him to stop selling his ‘spectrochrome’ machines, which produced a colored light that were supposed to make people feel better. “The use of colored lights in healing is no new thing,” Thayer wrote. “One recalls that Babbit advocated use of yellow light for a physic. Our MFS Faber Birren will cite you books on the subject for the past two or three centuries. MFS George Starr White M.D., has had wide experience in the field.” Thayer went on to note that there were others selling color healing kits, including The Auratone Foundation of America, which was supported by Bing Crosby, and to reminisce about the “Art Institute of Light, which had a color organ, that was an esoteric fad in the 1920s. The other mention was the result of another Fortean challenging Birren. Marie P. Sweet (who has already been considered) accused Birren of giving insufficient credit to Wilhelm Ostwald. Thayer looked into the matter and disagreed, but still published Sweet’s own thoughts on color.

It wasn’t for another two years that Birren would appear in Doubt, again tangentially. Doubt 24 (April 1949) had a squib titled “No Wonder,” written by Thayer: “In a story about which ‘American’ books the Nippiness are now permitted to publish, Walter Simmons wrote to the Chicago Tribune from Tokyo, May 20, 1948, old style, stating that—‘The Japanese are puzzled by such titles as Selling With, by Faber Birren.’ One finds little to wonder at in that. The book is Selling with Color, by MFS Birren.”

Four years later, and Birren’s name made its last appearance in Doubt, this one an acknowledged tangent, but more substantive than any of the others. In Doubt 42 (October 1953), Thayer catalogued books suggested by a new member, J. T. Boulton. Among them was Ernest Lehrs Man or Matter which Thayer glossed as “an understanding of Nature on the basis of Goethe’s Method of training observation and thought.” It included a “vigorous attack on Newtonian optics in particular.” After rehearsing some more of the contents, Thayer noted “Incidentally, our own color man—Faber Birren—is very cordial to Goethe’s optics.”

All of which leaves very little Forteanism on Birren’s part. What seems more important is his friendship with Thayer. Damon Knight—the science fiction writer—contacted him in 1968 when he was compiling information for a biography of Fort. Brian was one of the few to know that Thayer had donated material to the New York Public Library (these were mostly Fort’s notes) and also offered Knight some biographical information on Thayer, including the fact that he wrote his manuscripts by hand (the bulk of the remaining material he donated to the NYPL were handwritten drafts of Mona Lisa.) But Birren noted that Thayer put strains on their friendship. Although they had known each other for a long time, he said he could not stand to be in Thayer’s company for very long—he was too contentious, too rude.