A nomadic Fortean who traveled—and tested the limits—of Great Britain’s declining empire.

Eustace Guillan Hopper was born in 1905 to Thomas Henry Hopper and Annie (Whitelock) Hopper. They lived in Surrey, England, where Thomas worked as a clerk for the port authority. Eustace had an older sister, Muriel, born some six years before him. Eustace was baptized at Christ Church, New Malden, which was evangelically Anglican. Apparently, as a youth, he became fascinated by Gypsies and made friends with those in Surrey. He was also bitten by the traveling bug.

Hopper was too young for the Great War, and I have no records for him in the 1920s, likely because he was traveling. He started an article in a 1946 issue of The Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society: “In 1929 I was on the border between Brazil and Uruguay. Don’t ask me what I was doing. I was following my nose and it had led me from Rio to São Paulo down through Brazil into the State of Rio Grande and then along the frontier through the pleasant little towns where a man could lounge in the shade of a café without worrying about mañana.” He met up with a band of Romani there, who contrasted poorly with those he knew as a youth—they were dirtier, more larcenous—and then traveled along some more, through Paraguay and onto Bolivia. Ran out of cash, he worked a while, slowly making his way back to Montevideo. He may also have been a Latin American correspondent for the BBC.

Eustace Guillan Hopper was born in 1905 to Thomas Henry Hopper and Annie (Whitelock) Hopper. They lived in Surrey, England, where Thomas worked as a clerk for the port authority. Eustace had an older sister, Muriel, born some six years before him. Eustace was baptized at Christ Church, New Malden, which was evangelically Anglican. Apparently, as a youth, he became fascinated by Gypsies and made friends with those in Surrey. He was also bitten by the traveling bug.

Hopper was too young for the Great War, and I have no records for him in the 1920s, likely because he was traveling. He started an article in a 1946 issue of The Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society: “In 1929 I was on the border between Brazil and Uruguay. Don’t ask me what I was doing. I was following my nose and it had led me from Rio to São Paulo down through Brazil into the State of Rio Grande and then along the frontier through the pleasant little towns where a man could lounge in the shade of a café without worrying about mañana.” He met up with a band of Romani there, who contrasted poorly with those he knew as a youth—they were dirtier, more larcenous—and then traveled along some more, through Paraguay and onto Bolivia. Ran out of cash, he worked a while, slowly making his way back to Montevideo. He may also have been a Latin American correspondent for the BBC.

He was back in England no later than 1932—and still traveling some, on a ship bound for Lisbon in March of that year. But he was settling down: he shows up in the Surrey electoral registers for 1932, 1933, and 1935. Those first two years he was living with his parents again. Early in 1935 he married a woman named Elsie. She is listed in the register under two different last names, Livingston and Richards, and so was apparently a widow or divorcée. In 1935, he and Elsie lived on London Road, in Surrey. The next year, they moved to London proper. Elsie gave birth to a son, which seemed to provoke mixed emotions in Hopper: in 1945 he wrote (again in The Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society), “The need for educating my son was the one thing that chained me down after years of wandering, and that is a debt which he will never be able to repay.”

So settled—or chained—he seems to have embarked upon a career of writing. Whether sales were enough to pay all of his bills or he did other work, I don’t know, but he seems to have been rather prolific. Between 1935 and 1946 he published 32 short stories in The Evening News, a London daily. Another three stories appeared in magazines, Short Story Magazine and The Passing Show and Everybody’s Magazine. He wrote the story for the 1935 British film “Expert’s Opinion.” An article on Gypsy magic appeared in a 1947 issue of The Occult Review, a British periodical that gave space to other Forteans, among them Harold T. Wilkins. He also had short stories printed (or reprinted) in several Australian periodicals.

The 1940s was also when he became involved with the Gypsy Lore Society. At the time, he was living in Middlesex, at least according to the Society’s records. Clearly, he’d been making a study of the Romani—in fact and fiction—for several years. He donated several classic works on the Gypsy’s to the Society. His own fiction at the time was based on Romani culture. And he was writing non-fiction articles on the subject, too, as in The Occult Review and the Society’s journal. The first, in 1945, was a response to an earlier article that suggested the State should settle the Gypsy’s now that the War was over, to educate them, for their own health, and to turn them into productive laborers. Hopper’s apoplectic response demonstrated his Romantic attachment to Romani culture:

“Even as I read his suggestions, a chill clutched at my heart and a vision passed before my eyes. I saw a great ugly chromium-plated, super-charged ministerial motor-caravan dashing around the country loaded with very earnest bespectacled young people, who would count and measure every camping-ground, weigh the children, and hand out little boxes of dehydrated hotchiwitchi to those camping in distressed areas. The end of it would be questions in the House regarding the great expense of the Ministry of Gypsies and the levying of a heavy tax on all who lead a free life of movement.”

Hoper went on to systematically knock down all of the arguments in favor of settlement: first that the Romani needed no education. They could survive of the land by what they learned from their own culture, more than could be said for the so-called civilized Europeans—who had just finished bombing the hell out of each other. As for hygiene—the word was “invented by manufacturers of nostrums containing a pennyworth of corrosive sublimate sold in a bottle marked 3s. 6d. Pity the poor unhealthy Gypsy with his coppery complexion! Regard ye the city clerk, hanging to a strap in the subterranean railway! Which is the finer man?” Again, Hopper pointed out that the Gypsies had a vast fund of practical knowledge for solving their ailments. As for settling down and working—the Gypsies already worked, he said, and settlement would cause no end of political headaches with the inevitable result that the Gypsies would be settled on the worst pieces of land. He concluded,

“Once you begin to plan the Gypsy life you have murdered the Gypsies. Planning and Gypsies are anathema to each other. The Gypsy’s place in the post-war world is secure. He only has to go on being what he is—a true Gypsy. Let him wander the countryside at his will and grant us the joy of surprising him now and then at a bend in the road or a break in the woodlands. Let us still retain that sad, sweet pleasure of envying him his way of life.”

For all the Romanticism, though, Hopper seemed a legitimate scholar. He published a paper on the history of the Romani in England. And in another article for the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society (in addition to the one recounting his less-than-ideal connection with the Gypsies of South America), he tore apart popular literature on the Romani as Romantic twaddle that was at odds with the very normal, very earthy experience of everyday Gypsies:

“The case against Gypsy fictions is a black one,” he wrote after surveying the literature. “In hundreds of works writers who knew little or nothing about the Dark Race have blackguarded, libelled [sic] and lied about them. As a result, instead of accepting the Romanies for what they are—a simple-sly race of people with just about the same proportions of good and evil that make up the rest of mankind—we have created a falsehood which cracks mercilessly on Romani shoulders every month of the year.”

There is a large break in Hopper’s writing career; his short stories didn’t appear in the Evening News between 1946 and 1961. He didn’t publish in The Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society after 1947 and is last listed as a member in 1948. It seems that around this time, he was motivated to travel again. His son—who had “chained” him to England—would not have been an adult yet, but perhaps he was old enough to travel now. Or perhaps the family broke up. What we do know is that Hopper lit out for the colonies, appearing in southern Africa in the late 1940s. (A 1960 article he wrote had him there for 15 years, but that doesn’t fit with his work on the Gypsies.)

In 1949, the Southern Rhodesia Natural Resources Board released a 32-page pamphlet called The Soil: Our Greatest Treasure. A Book about the Land You Live on. It had been prepared by E. Guillan Hopper. He seemed to be working as the Board’s spokesperson or in some public relations’ capacity. In that position, he wrote an article explaining the Board’s duty as “trustee of the natural resources of the Colony” for Veldtrust—official organ of a group combatting soil erosion in southern Africa. And it was soil erosion that really seemed to bother Hopper (or his superiors). He wrote other articles on the subject and made a broadcast in the capital Salisbury, which linked soil erosion to the spread of cancer, an announcement that was picked up by the organic gardening press. If World-Wide Mining Abstracts is to be believed, he was no longer with the Southern Rhodesia Natural Resources Board by 1955, but was consulting on mining work.

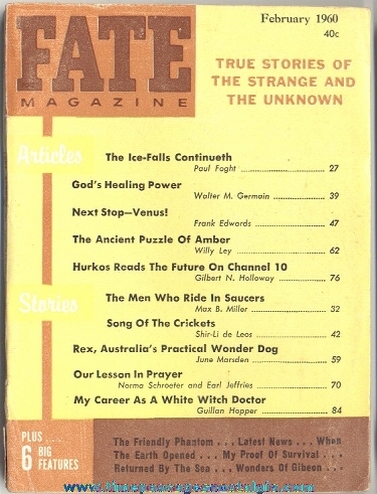

His own account is different, and doesn’t match up with the records located. Already I’ve mentioned that his timeline doesn’t seem correct. In that same 1960 article, published in Fate magazine, a slicker Fortean competitor of Doubt and, by that time, its sole successor, Hopper says that he spent those fifteen years in Central Africa as the colonial administrator of the “Southern Lake” district, which he described as southwest of Lake Tanganyika. I have found a few spare references to such a district, but from much earlier times. Currently, the area falls mostly in the country of Zambia. It was while working as a colonial administrator that Hopper claimed to have pierced the veil of secrecy that surrounded another misunderstood cultural institution: witch-doctoring. Witch doctors were the real power structure of Africa, he determined, and all of that continent’s troubles could be traced to colonizing countries quashing their practices.

Hopper saw himself as different. He respected the witch doctors. He trusted them. And he became one of them. The title of that Fate magazine article was the sensationalistic “My Career as a White Witch Doctor.”

According to Hopper, Her Majesty’s colonial officers receive a six-month sabbatical after every three years of service, which they are pressured to spend in the United Kingdom. He spent his, instead, being indoctrinated into a college of witch doctors. When he returned to his work after the half-year absence, it was a well-known fact that “Bwana” had joined the “occult fraternity.” He immediately set about using techniques he had learned: if he thought someone was lying, he would make that person go into a room, alone, and swear what they said onto the head of his personal devil, a small deity carved from wood on which he had applied camphor oil. He knew those who were lying would be too scared to really put their hand on the idol, and so would not smell of camphor. He reversed curses with flashy pyrotechnics. He practiced divining rituals. And for years, he said, there was no trouble in his district at all—the Mau Maus in Kenya knew to stay away, as did other potential troublemakers.

The story begs for skepticism, even if there wasn’t the problem of chronology. Hopper admitted that the tricks he used were mostly psychological—not real magic—but were effective just the same. The problem, though, is the story reads like the typical colonial claptrap about wily administrators using the superstitions of the backward people they administered against them—there’s a whole genre of this stuff, fictional and otherwise, like here. For all that Hopper claimed to respect the witch doctors, he Romanticized them to a greater degree in this story than he ever did the Romani—and at the same time patronized the other Africans to an astounding degree, making them all into superstitious simpletons.

Eventually, though, the golden age ended—well, Hopper’s version of it, anyway—brought down by a dour man of the cloth who came to the district and heard about the administrator’s unorthodox ways. He would have none of that. Hopper was fired—this was 1958, as anti-colonial movements in Africa continued to grow—and expelled from the territory under threat of being prosecuted as a witch. Exactly what happened next is unclear even from his story. On the one hand, Hopper decided to explore the rest of Africa, those parts (ever-increasing) not under British rule. One the other hand, he ended the story as so:

“Before leaving I saw my old friend the Chief, father of Kasembe. ‘It is sad that you are going,’ he said, ‘for you have been a father to us. But in 1963 the British will have gone and we shall rule our own land. Then you will return.’

“Yes, I shall return to tropical Africa at the end of three years because so long as there are mchawi—witches, warlocks and wizards—to terrify the African people, there is work for the witch doctor—even a white witch doctor!”

Perhaps he explored Africa some, and left in 1960. The details are too unclear to make sense of. But he does seem to have ended up back in England by 1960. That was the year Fate published his story. And by 1961, his stories appeared in The Evening News again: “Apish Trick,” September 16, 1961; “Her Taking Ways,” August 16, 1962; “Code for Murder,” September 12, 1962; “Grandma Became a Witch,” October 21, 1964. Or perhaps he was back as early as 1958. In that year he had an article published in one of Fate’s even more-sensationalistic competitors, Outdoor Adventure.

There’s another mystery, too, that comes out of the Fate article. Hopper is said t be married to the actress Beatrice Munro [Sic]. Presumably, the magazine meant Beatrice "Binnie" Mary Hale-Monro, who had an active career from the 1920s until the end of the 1950s. She would have been about the right age—born six years before Hopper—and it’s possible that they met; her career arc would support such a marriage, since she stopped performing in 1959. But I have found no supporting documentation beyond the mention in Fate. And, indeed, according to the electoral registry, she was not living with him in 1959 or 1960.

On top of these mysteries, there is also the Fortean ending: Hopper himself became a damned fact. The last original story from him seems to have appeared in 1964. (Some of his stuff was reprinted later.) But as far as I can find, there’s no record of his death. Bonnie Hale lived into the 1980s, all of that time in England, and, if indeed, he had married her, one might expect some official record of his passing. Perhaps, instead, as he insinuated in his article for Fate he returned to Africa some time in the early 1960s.

[Later edit, December 2014, Cliff Mark has sent me two copies of columns by Hopper that appeared in the Moroccan Mail. These dealt with the goings-on of local bars--so he had found his way to Morocco where he was doing journalism. Both articles are from November 1962. Morocco attracted other Forteans, before and after: William Burroughs was there in the early 1950s; Philip Lamantia in 1964.]

Perhaps he died there—or disappeared. Perhaps someone was collecting Eustaces. or Guillans. Or, most likely, Hoppers: the names too perfect for a peregrinating Fortean, isn’t it? Hopping from continent to continent? Hopping like those forever falling frogs.

Exactly how Hopper came across Charles Fort or the Fortean Society is one more mystery. Maybe there’s some clue buried in one of his stories, but they are very hard to get, and, at any rate, he doesn’t seem to have been very involved in the Society. (Which doesn’t mean he might not have been a committed Fortean—it just means I have to budget how much money and time I’m going to spend tracking down someone seemingly only tangentially related to the wider Fortean community.) His name appeared in three issues of Doubt: 15 (Summer 1946), 16 (January 1947), and 18 (July 1947), which was about the time he was writing about Gypsies and just before he left again for Africa. He wasn’t as active as some other members of the ilk, but he belongs to the class of Forteans who were involved with the Society during the 1940s but didn’t make the transition to the next decade. Part of that, no doubt, was his move from England to Africa—whichever part of that huge continent he inhabited—and there may have been other life circumstances, too, possibly a break with his family, and certainly a diminished if not finished interest in the Romani.

It’s certainly easy to see why Hopper might have been a Fortean. He shared with many others who joined Tiffany Thayer’s club a distrust for the government—even if he worked for it—a yearning for a freedom of the self away from the confining definitions of nationhood and science, and a Romantic valuation of alternative forms of knowledge—be they Gypsy or “witch doctor”—even if he thought them more practical methods of work than systems of thought. He ran in similar circles, publishing in some of the same journals. And he was a writer—and it was writers, especially, who were influenced by Fort, his style, his facts, his systems. All that, though, is speculation, informed by his biography but nothing proved.

Still, there’s nothing in his contributions to contradict these surmises. The first material he sent to Thayer was about the mysterious disappearance of Henry Payance, and his even more mysterious reappearance. Henry Payance, happily married, teetotaling, no friend of cigarettes—a hardworking barber by trade—went for a walk in April 1943. Fit and 38, he was never seen again . . . or was he? For post-War construction workers discovered in a damaged house being reconstructed a skeleton, that seemed to have only one bit of identification, and that named the former person Henry Payance. The problem was, the house was bombed in 1942. By the time that Hopper contributed the story—1946—he was already being labelled an MFS, which means he had joined sometime earlier, likely not much earlier.

The next contribution, also in a strictly Fortean vein, was grouped in a column Thayer put together on various ghost encounters. This one concerned a “mysterious luminous figure” in South Sweden that scared off the cattle. Reportedly, the ghost had been viewed before, during the war. There was no follow-up.

The final mention was brief, included under the heading “British Report”: “MFS Hopper is in the occult review with an article on Gypsy Magic.”

Which leaves us with two contributions. They reveal nothing of Hopper’s views of authority or politics necessarily, rather are in the mainstream of Fortean reports. That certainly suggests that Hopper was familiar with Fort and Fortean writing—but more than that cannot be said.

So settled—or chained—he seems to have embarked upon a career of writing. Whether sales were enough to pay all of his bills or he did other work, I don’t know, but he seems to have been rather prolific. Between 1935 and 1946 he published 32 short stories in The Evening News, a London daily. Another three stories appeared in magazines, Short Story Magazine and The Passing Show and Everybody’s Magazine. He wrote the story for the 1935 British film “Expert’s Opinion.” An article on Gypsy magic appeared in a 1947 issue of The Occult Review, a British periodical that gave space to other Forteans, among them Harold T. Wilkins. He also had short stories printed (or reprinted) in several Australian periodicals.

The 1940s was also when he became involved with the Gypsy Lore Society. At the time, he was living in Middlesex, at least according to the Society’s records. Clearly, he’d been making a study of the Romani—in fact and fiction—for several years. He donated several classic works on the Gypsy’s to the Society. His own fiction at the time was based on Romani culture. And he was writing non-fiction articles on the subject, too, as in The Occult Review and the Society’s journal. The first, in 1945, was a response to an earlier article that suggested the State should settle the Gypsy’s now that the War was over, to educate them, for their own health, and to turn them into productive laborers. Hopper’s apoplectic response demonstrated his Romantic attachment to Romani culture:

“Even as I read his suggestions, a chill clutched at my heart and a vision passed before my eyes. I saw a great ugly chromium-plated, super-charged ministerial motor-caravan dashing around the country loaded with very earnest bespectacled young people, who would count and measure every camping-ground, weigh the children, and hand out little boxes of dehydrated hotchiwitchi to those camping in distressed areas. The end of it would be questions in the House regarding the great expense of the Ministry of Gypsies and the levying of a heavy tax on all who lead a free life of movement.”

Hoper went on to systematically knock down all of the arguments in favor of settlement: first that the Romani needed no education. They could survive of the land by what they learned from their own culture, more than could be said for the so-called civilized Europeans—who had just finished bombing the hell out of each other. As for hygiene—the word was “invented by manufacturers of nostrums containing a pennyworth of corrosive sublimate sold in a bottle marked 3s. 6d. Pity the poor unhealthy Gypsy with his coppery complexion! Regard ye the city clerk, hanging to a strap in the subterranean railway! Which is the finer man?” Again, Hopper pointed out that the Gypsies had a vast fund of practical knowledge for solving their ailments. As for settling down and working—the Gypsies already worked, he said, and settlement would cause no end of political headaches with the inevitable result that the Gypsies would be settled on the worst pieces of land. He concluded,

“Once you begin to plan the Gypsy life you have murdered the Gypsies. Planning and Gypsies are anathema to each other. The Gypsy’s place in the post-war world is secure. He only has to go on being what he is—a true Gypsy. Let him wander the countryside at his will and grant us the joy of surprising him now and then at a bend in the road or a break in the woodlands. Let us still retain that sad, sweet pleasure of envying him his way of life.”

For all the Romanticism, though, Hopper seemed a legitimate scholar. He published a paper on the history of the Romani in England. And in another article for the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society (in addition to the one recounting his less-than-ideal connection with the Gypsies of South America), he tore apart popular literature on the Romani as Romantic twaddle that was at odds with the very normal, very earthy experience of everyday Gypsies:

“The case against Gypsy fictions is a black one,” he wrote after surveying the literature. “In hundreds of works writers who knew little or nothing about the Dark Race have blackguarded, libelled [sic] and lied about them. As a result, instead of accepting the Romanies for what they are—a simple-sly race of people with just about the same proportions of good and evil that make up the rest of mankind—we have created a falsehood which cracks mercilessly on Romani shoulders every month of the year.”

There is a large break in Hopper’s writing career; his short stories didn’t appear in the Evening News between 1946 and 1961. He didn’t publish in The Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society after 1947 and is last listed as a member in 1948. It seems that around this time, he was motivated to travel again. His son—who had “chained” him to England—would not have been an adult yet, but perhaps he was old enough to travel now. Or perhaps the family broke up. What we do know is that Hopper lit out for the colonies, appearing in southern Africa in the late 1940s. (A 1960 article he wrote had him there for 15 years, but that doesn’t fit with his work on the Gypsies.)

In 1949, the Southern Rhodesia Natural Resources Board released a 32-page pamphlet called The Soil: Our Greatest Treasure. A Book about the Land You Live on. It had been prepared by E. Guillan Hopper. He seemed to be working as the Board’s spokesperson or in some public relations’ capacity. In that position, he wrote an article explaining the Board’s duty as “trustee of the natural resources of the Colony” for Veldtrust—official organ of a group combatting soil erosion in southern Africa. And it was soil erosion that really seemed to bother Hopper (or his superiors). He wrote other articles on the subject and made a broadcast in the capital Salisbury, which linked soil erosion to the spread of cancer, an announcement that was picked up by the organic gardening press. If World-Wide Mining Abstracts is to be believed, he was no longer with the Southern Rhodesia Natural Resources Board by 1955, but was consulting on mining work.

His own account is different, and doesn’t match up with the records located. Already I’ve mentioned that his timeline doesn’t seem correct. In that same 1960 article, published in Fate magazine, a slicker Fortean competitor of Doubt and, by that time, its sole successor, Hopper says that he spent those fifteen years in Central Africa as the colonial administrator of the “Southern Lake” district, which he described as southwest of Lake Tanganyika. I have found a few spare references to such a district, but from much earlier times. Currently, the area falls mostly in the country of Zambia. It was while working as a colonial administrator that Hopper claimed to have pierced the veil of secrecy that surrounded another misunderstood cultural institution: witch-doctoring. Witch doctors were the real power structure of Africa, he determined, and all of that continent’s troubles could be traced to colonizing countries quashing their practices.

Hopper saw himself as different. He respected the witch doctors. He trusted them. And he became one of them. The title of that Fate magazine article was the sensationalistic “My Career as a White Witch Doctor.”

According to Hopper, Her Majesty’s colonial officers receive a six-month sabbatical after every three years of service, which they are pressured to spend in the United Kingdom. He spent his, instead, being indoctrinated into a college of witch doctors. When he returned to his work after the half-year absence, it was a well-known fact that “Bwana” had joined the “occult fraternity.” He immediately set about using techniques he had learned: if he thought someone was lying, he would make that person go into a room, alone, and swear what they said onto the head of his personal devil, a small deity carved from wood on which he had applied camphor oil. He knew those who were lying would be too scared to really put their hand on the idol, and so would not smell of camphor. He reversed curses with flashy pyrotechnics. He practiced divining rituals. And for years, he said, there was no trouble in his district at all—the Mau Maus in Kenya knew to stay away, as did other potential troublemakers.

The story begs for skepticism, even if there wasn’t the problem of chronology. Hopper admitted that the tricks he used were mostly psychological—not real magic—but were effective just the same. The problem, though, is the story reads like the typical colonial claptrap about wily administrators using the superstitions of the backward people they administered against them—there’s a whole genre of this stuff, fictional and otherwise, like here. For all that Hopper claimed to respect the witch doctors, he Romanticized them to a greater degree in this story than he ever did the Romani—and at the same time patronized the other Africans to an astounding degree, making them all into superstitious simpletons.

Eventually, though, the golden age ended—well, Hopper’s version of it, anyway—brought down by a dour man of the cloth who came to the district and heard about the administrator’s unorthodox ways. He would have none of that. Hopper was fired—this was 1958, as anti-colonial movements in Africa continued to grow—and expelled from the territory under threat of being prosecuted as a witch. Exactly what happened next is unclear even from his story. On the one hand, Hopper decided to explore the rest of Africa, those parts (ever-increasing) not under British rule. One the other hand, he ended the story as so:

“Before leaving I saw my old friend the Chief, father of Kasembe. ‘It is sad that you are going,’ he said, ‘for you have been a father to us. But in 1963 the British will have gone and we shall rule our own land. Then you will return.’

“Yes, I shall return to tropical Africa at the end of three years because so long as there are mchawi—witches, warlocks and wizards—to terrify the African people, there is work for the witch doctor—even a white witch doctor!”

Perhaps he explored Africa some, and left in 1960. The details are too unclear to make sense of. But he does seem to have ended up back in England by 1960. That was the year Fate published his story. And by 1961, his stories appeared in The Evening News again: “Apish Trick,” September 16, 1961; “Her Taking Ways,” August 16, 1962; “Code for Murder,” September 12, 1962; “Grandma Became a Witch,” October 21, 1964. Or perhaps he was back as early as 1958. In that year he had an article published in one of Fate’s even more-sensationalistic competitors, Outdoor Adventure.

There’s another mystery, too, that comes out of the Fate article. Hopper is said t be married to the actress Beatrice Munro [Sic]. Presumably, the magazine meant Beatrice "Binnie" Mary Hale-Monro, who had an active career from the 1920s until the end of the 1950s. She would have been about the right age—born six years before Hopper—and it’s possible that they met; her career arc would support such a marriage, since she stopped performing in 1959. But I have found no supporting documentation beyond the mention in Fate. And, indeed, according to the electoral registry, she was not living with him in 1959 or 1960.

On top of these mysteries, there is also the Fortean ending: Hopper himself became a damned fact. The last original story from him seems to have appeared in 1964. (Some of his stuff was reprinted later.) But as far as I can find, there’s no record of his death. Bonnie Hale lived into the 1980s, all of that time in England, and, if indeed, he had married her, one might expect some official record of his passing. Perhaps, instead, as he insinuated in his article for Fate he returned to Africa some time in the early 1960s.

[Later edit, December 2014, Cliff Mark has sent me two copies of columns by Hopper that appeared in the Moroccan Mail. These dealt with the goings-on of local bars--so he had found his way to Morocco where he was doing journalism. Both articles are from November 1962. Morocco attracted other Forteans, before and after: William Burroughs was there in the early 1950s; Philip Lamantia in 1964.]

Perhaps he died there—or disappeared. Perhaps someone was collecting Eustaces. or Guillans. Or, most likely, Hoppers: the names too perfect for a peregrinating Fortean, isn’t it? Hopping from continent to continent? Hopping like those forever falling frogs.

Exactly how Hopper came across Charles Fort or the Fortean Society is one more mystery. Maybe there’s some clue buried in one of his stories, but they are very hard to get, and, at any rate, he doesn’t seem to have been very involved in the Society. (Which doesn’t mean he might not have been a committed Fortean—it just means I have to budget how much money and time I’m going to spend tracking down someone seemingly only tangentially related to the wider Fortean community.) His name appeared in three issues of Doubt: 15 (Summer 1946), 16 (January 1947), and 18 (July 1947), which was about the time he was writing about Gypsies and just before he left again for Africa. He wasn’t as active as some other members of the ilk, but he belongs to the class of Forteans who were involved with the Society during the 1940s but didn’t make the transition to the next decade. Part of that, no doubt, was his move from England to Africa—whichever part of that huge continent he inhabited—and there may have been other life circumstances, too, possibly a break with his family, and certainly a diminished if not finished interest in the Romani.

It’s certainly easy to see why Hopper might have been a Fortean. He shared with many others who joined Tiffany Thayer’s club a distrust for the government—even if he worked for it—a yearning for a freedom of the self away from the confining definitions of nationhood and science, and a Romantic valuation of alternative forms of knowledge—be they Gypsy or “witch doctor”—even if he thought them more practical methods of work than systems of thought. He ran in similar circles, publishing in some of the same journals. And he was a writer—and it was writers, especially, who were influenced by Fort, his style, his facts, his systems. All that, though, is speculation, informed by his biography but nothing proved.

Still, there’s nothing in his contributions to contradict these surmises. The first material he sent to Thayer was about the mysterious disappearance of Henry Payance, and his even more mysterious reappearance. Henry Payance, happily married, teetotaling, no friend of cigarettes—a hardworking barber by trade—went for a walk in April 1943. Fit and 38, he was never seen again . . . or was he? For post-War construction workers discovered in a damaged house being reconstructed a skeleton, that seemed to have only one bit of identification, and that named the former person Henry Payance. The problem was, the house was bombed in 1942. By the time that Hopper contributed the story—1946—he was already being labelled an MFS, which means he had joined sometime earlier, likely not much earlier.

The next contribution, also in a strictly Fortean vein, was grouped in a column Thayer put together on various ghost encounters. This one concerned a “mysterious luminous figure” in South Sweden that scared off the cattle. Reportedly, the ghost had been viewed before, during the war. There was no follow-up.

The final mention was brief, included under the heading “British Report”: “MFS Hopper is in the occult review with an article on Gypsy Magic.”

Which leaves us with two contributions. They reveal nothing of Hopper’s views of authority or politics necessarily, rather are in the mainstream of Fortean reports. That certainly suggests that Hopper was familiar with Fort and Fortean writing—but more than that cannot be said.