This is the sum total of material on Donald J. Snively in “The Fortean Society Magazine”:

“Thanks to Members

…..

Donald J. Snively

….”

It comes from the 3rd issue, dated January 1940—a list of members who have sent in material. That’s it. The name never appears again, and there are no distinguishing characteristics.

Except that the name is unusual. I Googled it. And there was a batch of correspondence between a Donald J. Snively and a Howard D. Snively—engineer with GE—at the Schenectady Museum of Innovation and Science. To my amazement, the correspondence was indeed from the same Donald J. Snively. And it allowed me to find a bit more information on him—not a lot, to be sure, but more than I could have hoped. I assumed he was just going to be another Fortean I know only by name, but that isn’t the case.

Donald J. Snively was born 25 October 1906 to Pius D. Snively and Elizabeth Mary (Karrer). He was the family’s third son, coming some two decades after the north of his brother Homer in 1887 and sister Carrie in 1888. (They had been married about 1886.) Pius’s parents both came from Ohio; Lizzie—as she was known—was first generation, her parents having come from Germany and Switzerland. Pius was a tinner and Lizzie a seamstress; they also had a number of boarders over the years.

Exactly why there was such a gap between the first two children and the third is unknown. But it had the effect of making Donald close to his nephew, Howard, son of Homer and only four years his junior, having been born 30 January 1911. Howard’s middle name was Donald, which seems to have been a family name, but also would have connected uncle and nephew.

There is some evidence that, in 1913, when Donald was seven, the family’s situation was disrupted. A Pius D. Snively is recorded as marrying one Adeline Schwing in West Virginia. And the 1915 city directory for Canton, Ohio, has a listing for both Adeline Snively and Pius D. Snively. But oddly, that same directory lists Lizzie as widowed. I can find no record of another Pius D. Snively, though, so it seems unlikely that Lizzie’s husband had died while Adeline’s husband moved into town. And I can find no records definitively tied to this Adeline (Schwing) Snively.

Then, in 1917, Pius D. Snively died. The city directory that year listed both Adilene and Lizzy as widow of Pius D. Snively. Perhaps there had been two Pius D. Snivelys in town, and Lizzie's faithful husband died around 1913. It's possible. Regardless, Donald lost his father when he was no older than eleven.

By 1920, Donald was living with his grandmother—Lizzie’s mom—his own mother and five boarders. Apparently, the boarders provided all of the family’s income, as none are listed as having jobs. (Donald was only 11.) Of course, there’s always the possibility that they did little projects—Lizzy, after all, had been a seamstress before.

The 1920s and early 1930s saw the further withering away of Donald’s immediate family. His sister died in 1927. And his grandmother, who had been born in 1843, seems to have died sometime before 1930. He was living with his mother in 1930, working as a printer, and there was only a single boarder. On 28 February 1934, Lizzie passed. That same year, Howard suddenly packed up and left for Schenectady and a job with G.E.—so quickly that Donald was surprised.

That year began the correspondence between Uncle and Nephew. Nine letters are preserved in the Schenectady Museum, all from Donald to Howard, written between October and November 1937. They are chatty and revealing of Donald’s interests—particularly those he shares with Howard. There is very little family gossip and, going by these letters, Donald, who would never marry, spent most of his free time alone.

He loved music, and was very interested in radios as technologies, studying their specs, and helping others by rebuilding theirs. Many of the letters include Donald’s advice to Howard on which radio to purchase, which is especially striking because Howard was an engineer. He collected thousands of records. Donald was also a movie aficionado, and spent a great deal of space discussing new movies and the actors in them. He and two of Howard’s cousins, Glenn and Rich, spent a lot of time arguing over which actress she play the title role in H. Rider Haggard’s “She,” if ever a movie was made. There’s also some commentary on Donald’s business, which was very slow in 1934 but picked up enough over the next three years that he took on Glenn as an assistant and, later, Rich, too.

But, as the discussion over “She” indicated, first and foremost Donald comes across in these letters as a reader—a reader of eccentric tastes. He collected all sorts of books: ethnographic descriptions of sex in other culture, Greek plays, poetry anthologies, ancient history, mysticism, Theosophy, and Polynesian myths. He was compiling a vocabulary of dirty words, tracing their etymology to Greek and Latin. When he read The Marquis de Sade, he was not shocked. Donald became a fan of James Cabell Branch. (Jurgen was his favorite.) He studied popular literary criticism, taking the New York Times to keep up with new books but switching to the Herald Tribune because he found its judgments more in accord with his.

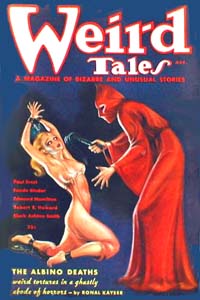

And he read pulp fiction. He was a fan of Tiffany Thayer’s and wondered why Thayer did not get more critical support—his language was as pungent as Dashiell Hammett’s, he noted, and far better than Erle Stanley Gardner’s. Over the years, he subscribed to Adventure and Detective Fiction and Weird Tales and Argosy and Blue Book, but also wondered why—many of the magazines had suffered in quality, he thought, and books were becoming the better method for reading: wait for the inevitable reprint and get the story all at once (without having to pay for Gardner’s terrible stuff). He collected Abe Merritt’s work. He liked Henry Kuttner—much more than Robert Bloch, who he dismissed as another Lovecraft imitator—and thought Stanley Weinbaum was pretty good. Donald was dismayed when he caught that C.L. Moore was a woman: “What are things coming to anyway?” (What would he have thought had he known that Moore and Kuttner would marry in 1940?) He watched, too, as the writers moved about, noting that the Weird Tales writer Frank Owen went to work for Claude Kendall and followed Theda Kenyon from that magazine’s pages to the book “Witches Still Live.” Fortunately, Canton had an excellent bookstore:

“Our bookstore is about as good as they come. Every now and then they buy out some bankrupt store somewhere and they get some good bargains.”

He was especially enthusiastic about James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon”:

“‘Lost Horizon’ in spite of a lot of high-brow praise is a just a darn good yarn which has been compared with the work of every one except the author whose works it most nearly resembles—Rider Haggard. It’s my idea of how a story should be written.”

The connections between Donald Snively and Forteanism thus become obvious: his interest in Thayer, his general intellectual tendencies, and that Fort was a well-known part of weird literature in the 1930s.

First, Thayer.

Thayer’s “Kings and Numbers” appeared in September 1934, and Donald Snively was recommending it by October. For all the enthusiasm, though—and it is genuine—Snively seemed to note that Thayer had a basic unseriousness about him. He wrote Howard:

“If you haven’t read ‘Kings and Numbers’ yet, be sure and get it. It’s certainly different. It’s mostly annotations from reference books with the language in Thayer’s best modern style. I don’t see how the book reviews can make such a fuss over Hammett and Gardner etc and ignore Thayer. And wait till you see the partial list of reference books he gives in the back of the book. Everything from the Bible to ‘Wild Talents’ by Charles Fort. Thayer claims its the first of a series of who knows how many books dealing with the descendants of Pericles. He even gives the chapter heads of the next book In case he does bring it up to date he’ll probably prove that hes [sic] the last member of the family. The book contains a lot of short stories in all styles including a story of the traveling salesman and the farmers daughter which is real good. The story picked as the oldest one in the world is the one used in the plot of ‘Bulldog Drummond Strikes Back’ in the movies.”

By the following month, he had acquainted himself with Thayer’s oeuvre, enough that he could compare The Greek, from three years before, to the rest of his output: ““I think ‘The Greek’ is about Thayers best. It comes nearer to the spirit of ‘Kings and Numbers’ than the others.”

And then there is Snively’s general intellectual inclinations as revealed in these letters. He liked rescuing lost things—creating an etymology of profanity, for example—“Its more interesting than it sounds because, as you can imagine, there’s not much written on the subject. I got hold of Andrews’ Latin Lexicon second-hand and if you think the Greeks had a word for it, the Romans had three,” he said. And he reveled in odd interpretations, recommending a book on ancient pyramids to Howard: “I bought Davidsons “Great Pyramid”—and theres a book for an engineer. All prophecy, religious, etc aside, thats an interesting subject. And are the textbooks mixed up!” On the contrary, he did not like it when “Astounding Stories” became too scientific. (And would later worry that Howard was too scientific-minded to appreciate Fort.) Finally, while one doesn’t want to put too much weight on such connections, there is the fact that Snively rated Burton Rascoe his favorite book reviewer—Burton Rascoe who sung Fort’s praises in the New York Herald Tribune and was a founding member of the Society—and that Alexander Woollcott, from his perch in The New Yorker and as a member of the Algonquin Table, encouraged his readers to pick up James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon”—Woollcott, who was another founding member of the Society and gave Fort a boost in McCall’s.

Given Donald Snively’s interest in Weird Fiction, the occult and mystical, it is no surprise that in September 1936 he announced he was collecting Fort’s four books—certainly h had come across references to them often enough, including in Thayer’s writings. He was twenty-nine at the time, young enough he missed the enthusiasm that greeted Fort’s first book and probably, as well, the hullabaloo made about “Lo!.” He told Howard:

“I’m also getting Fort’s stuff. I only need “New Lands,” but I need it Bad. It cost me $4.50 for “The Book of the Damned” but its worth it. “Lo!” is still in print and more complete than the abridgement [sic] in Astounding Stories. I got Wild Talents at remainder prices.”

He recognized that Fort’s writings were a kind of intellectual play, and not to everyone’s tastes:

“I wonder if you’re too much a scientist, these days to get a kick out of Fort. If you want to read any, just say so and I’ll send em. Personally I think the guy is good.”

A year later, he had completed his collection, and encouraged Howard to be on the look-out for any more copies of Fort’s books. “Buy any Fort books, especially ‘New Lands.’ They are all out of print and cant help but go up. I paid $4.00 for ‘New Lands’ and it took me a year to get it.”

By that point, as well, the Fortean Society had relaunched, and Snively joined. He wrote Thayer praising his books—and Thayer’s answer confirmed that interest in the Society (and Thayer) was subversive, which is what Snively seemed to be looking for in much of his reading:

“I told Thayer I liked [Geek and] Kings and Numbers best of his books and he wrote that it was a penitentiary offense in some states to like those two. And how about Ohio?”

But that didn’t mean he took seriously Thayer, or even the Society—not anymore than he had ever taken Thayer, or, it seems, Fort. He wrote Howard:

“I am now a member in good standing in the Fortean Society—if thats [sic] anything to brag about. Tiffany Thayer is secretary, editor [sic] chief heckler etc. Dues are $2.00 a year including a magazine, bulletins, etc. You would make a good member. Even if you dont [sic] go for Fort Thayer is screwy enough. The address is “The Fortean Society”—444 Madison Ave., N.Y.—and ask for the first two copies of “The Fortean.”

That was from the last letter in the Museum of Innovation and Science’s archives. Why did not more survive? (Was there emote to survive?) What did Snively think of the Society as it developed? Why was he mentioned only once in the Society’s magazine? Did he drop out? None of these questions have answers.

Howard stayed with GE, dying in 1992. Donald stayed in Canton, a printer, and died early, in September 1954, just a month before his 48th birthday.

“Thanks to Members

…..

Donald J. Snively

….”

It comes from the 3rd issue, dated January 1940—a list of members who have sent in material. That’s it. The name never appears again, and there are no distinguishing characteristics.

Except that the name is unusual. I Googled it. And there was a batch of correspondence between a Donald J. Snively and a Howard D. Snively—engineer with GE—at the Schenectady Museum of Innovation and Science. To my amazement, the correspondence was indeed from the same Donald J. Snively. And it allowed me to find a bit more information on him—not a lot, to be sure, but more than I could have hoped. I assumed he was just going to be another Fortean I know only by name, but that isn’t the case.

Donald J. Snively was born 25 October 1906 to Pius D. Snively and Elizabeth Mary (Karrer). He was the family’s third son, coming some two decades after the north of his brother Homer in 1887 and sister Carrie in 1888. (They had been married about 1886.) Pius’s parents both came from Ohio; Lizzie—as she was known—was first generation, her parents having come from Germany and Switzerland. Pius was a tinner and Lizzie a seamstress; they also had a number of boarders over the years.

Exactly why there was such a gap between the first two children and the third is unknown. But it had the effect of making Donald close to his nephew, Howard, son of Homer and only four years his junior, having been born 30 January 1911. Howard’s middle name was Donald, which seems to have been a family name, but also would have connected uncle and nephew.

There is some evidence that, in 1913, when Donald was seven, the family’s situation was disrupted. A Pius D. Snively is recorded as marrying one Adeline Schwing in West Virginia. And the 1915 city directory for Canton, Ohio, has a listing for both Adeline Snively and Pius D. Snively. But oddly, that same directory lists Lizzie as widowed. I can find no record of another Pius D. Snively, though, so it seems unlikely that Lizzie’s husband had died while Adeline’s husband moved into town. And I can find no records definitively tied to this Adeline (Schwing) Snively.

Then, in 1917, Pius D. Snively died. The city directory that year listed both Adilene and Lizzy as widow of Pius D. Snively. Perhaps there had been two Pius D. Snivelys in town, and Lizzie's faithful husband died around 1913. It's possible. Regardless, Donald lost his father when he was no older than eleven.

By 1920, Donald was living with his grandmother—Lizzie’s mom—his own mother and five boarders. Apparently, the boarders provided all of the family’s income, as none are listed as having jobs. (Donald was only 11.) Of course, there’s always the possibility that they did little projects—Lizzy, after all, had been a seamstress before.

The 1920s and early 1930s saw the further withering away of Donald’s immediate family. His sister died in 1927. And his grandmother, who had been born in 1843, seems to have died sometime before 1930. He was living with his mother in 1930, working as a printer, and there was only a single boarder. On 28 February 1934, Lizzie passed. That same year, Howard suddenly packed up and left for Schenectady and a job with G.E.—so quickly that Donald was surprised.

That year began the correspondence between Uncle and Nephew. Nine letters are preserved in the Schenectady Museum, all from Donald to Howard, written between October and November 1937. They are chatty and revealing of Donald’s interests—particularly those he shares with Howard. There is very little family gossip and, going by these letters, Donald, who would never marry, spent most of his free time alone.

He loved music, and was very interested in radios as technologies, studying their specs, and helping others by rebuilding theirs. Many of the letters include Donald’s advice to Howard on which radio to purchase, which is especially striking because Howard was an engineer. He collected thousands of records. Donald was also a movie aficionado, and spent a great deal of space discussing new movies and the actors in them. He and two of Howard’s cousins, Glenn and Rich, spent a lot of time arguing over which actress she play the title role in H. Rider Haggard’s “She,” if ever a movie was made. There’s also some commentary on Donald’s business, which was very slow in 1934 but picked up enough over the next three years that he took on Glenn as an assistant and, later, Rich, too.

But, as the discussion over “She” indicated, first and foremost Donald comes across in these letters as a reader—a reader of eccentric tastes. He collected all sorts of books: ethnographic descriptions of sex in other culture, Greek plays, poetry anthologies, ancient history, mysticism, Theosophy, and Polynesian myths. He was compiling a vocabulary of dirty words, tracing their etymology to Greek and Latin. When he read The Marquis de Sade, he was not shocked. Donald became a fan of James Cabell Branch. (Jurgen was his favorite.) He studied popular literary criticism, taking the New York Times to keep up with new books but switching to the Herald Tribune because he found its judgments more in accord with his.

And he read pulp fiction. He was a fan of Tiffany Thayer’s and wondered why Thayer did not get more critical support—his language was as pungent as Dashiell Hammett’s, he noted, and far better than Erle Stanley Gardner’s. Over the years, he subscribed to Adventure and Detective Fiction and Weird Tales and Argosy and Blue Book, but also wondered why—many of the magazines had suffered in quality, he thought, and books were becoming the better method for reading: wait for the inevitable reprint and get the story all at once (without having to pay for Gardner’s terrible stuff). He collected Abe Merritt’s work. He liked Henry Kuttner—much more than Robert Bloch, who he dismissed as another Lovecraft imitator—and thought Stanley Weinbaum was pretty good. Donald was dismayed when he caught that C.L. Moore was a woman: “What are things coming to anyway?” (What would he have thought had he known that Moore and Kuttner would marry in 1940?) He watched, too, as the writers moved about, noting that the Weird Tales writer Frank Owen went to work for Claude Kendall and followed Theda Kenyon from that magazine’s pages to the book “Witches Still Live.” Fortunately, Canton had an excellent bookstore:

“Our bookstore is about as good as they come. Every now and then they buy out some bankrupt store somewhere and they get some good bargains.”

He was especially enthusiastic about James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon”:

“‘Lost Horizon’ in spite of a lot of high-brow praise is a just a darn good yarn which has been compared with the work of every one except the author whose works it most nearly resembles—Rider Haggard. It’s my idea of how a story should be written.”

The connections between Donald Snively and Forteanism thus become obvious: his interest in Thayer, his general intellectual tendencies, and that Fort was a well-known part of weird literature in the 1930s.

First, Thayer.

Thayer’s “Kings and Numbers” appeared in September 1934, and Donald Snively was recommending it by October. For all the enthusiasm, though—and it is genuine—Snively seemed to note that Thayer had a basic unseriousness about him. He wrote Howard:

“If you haven’t read ‘Kings and Numbers’ yet, be sure and get it. It’s certainly different. It’s mostly annotations from reference books with the language in Thayer’s best modern style. I don’t see how the book reviews can make such a fuss over Hammett and Gardner etc and ignore Thayer. And wait till you see the partial list of reference books he gives in the back of the book. Everything from the Bible to ‘Wild Talents’ by Charles Fort. Thayer claims its the first of a series of who knows how many books dealing with the descendants of Pericles. He even gives the chapter heads of the next book In case he does bring it up to date he’ll probably prove that hes [sic] the last member of the family. The book contains a lot of short stories in all styles including a story of the traveling salesman and the farmers daughter which is real good. The story picked as the oldest one in the world is the one used in the plot of ‘Bulldog Drummond Strikes Back’ in the movies.”

By the following month, he had acquainted himself with Thayer’s oeuvre, enough that he could compare The Greek, from three years before, to the rest of his output: ““I think ‘The Greek’ is about Thayers best. It comes nearer to the spirit of ‘Kings and Numbers’ than the others.”

And then there is Snively’s general intellectual inclinations as revealed in these letters. He liked rescuing lost things—creating an etymology of profanity, for example—“Its more interesting than it sounds because, as you can imagine, there’s not much written on the subject. I got hold of Andrews’ Latin Lexicon second-hand and if you think the Greeks had a word for it, the Romans had three,” he said. And he reveled in odd interpretations, recommending a book on ancient pyramids to Howard: “I bought Davidsons “Great Pyramid”—and theres a book for an engineer. All prophecy, religious, etc aside, thats an interesting subject. And are the textbooks mixed up!” On the contrary, he did not like it when “Astounding Stories” became too scientific. (And would later worry that Howard was too scientific-minded to appreciate Fort.) Finally, while one doesn’t want to put too much weight on such connections, there is the fact that Snively rated Burton Rascoe his favorite book reviewer—Burton Rascoe who sung Fort’s praises in the New York Herald Tribune and was a founding member of the Society—and that Alexander Woollcott, from his perch in The New Yorker and as a member of the Algonquin Table, encouraged his readers to pick up James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon”—Woollcott, who was another founding member of the Society and gave Fort a boost in McCall’s.

Given Donald Snively’s interest in Weird Fiction, the occult and mystical, it is no surprise that in September 1936 he announced he was collecting Fort’s four books—certainly h had come across references to them often enough, including in Thayer’s writings. He was twenty-nine at the time, young enough he missed the enthusiasm that greeted Fort’s first book and probably, as well, the hullabaloo made about “Lo!.” He told Howard:

“I’m also getting Fort’s stuff. I only need “New Lands,” but I need it Bad. It cost me $4.50 for “The Book of the Damned” but its worth it. “Lo!” is still in print and more complete than the abridgement [sic] in Astounding Stories. I got Wild Talents at remainder prices.”

He recognized that Fort’s writings were a kind of intellectual play, and not to everyone’s tastes:

“I wonder if you’re too much a scientist, these days to get a kick out of Fort. If you want to read any, just say so and I’ll send em. Personally I think the guy is good.”

A year later, he had completed his collection, and encouraged Howard to be on the look-out for any more copies of Fort’s books. “Buy any Fort books, especially ‘New Lands.’ They are all out of print and cant help but go up. I paid $4.00 for ‘New Lands’ and it took me a year to get it.”

By that point, as well, the Fortean Society had relaunched, and Snively joined. He wrote Thayer praising his books—and Thayer’s answer confirmed that interest in the Society (and Thayer) was subversive, which is what Snively seemed to be looking for in much of his reading:

“I told Thayer I liked [Geek and] Kings and Numbers best of his books and he wrote that it was a penitentiary offense in some states to like those two. And how about Ohio?”

But that didn’t mean he took seriously Thayer, or even the Society—not anymore than he had ever taken Thayer, or, it seems, Fort. He wrote Howard:

“I am now a member in good standing in the Fortean Society—if thats [sic] anything to brag about. Tiffany Thayer is secretary, editor [sic] chief heckler etc. Dues are $2.00 a year including a magazine, bulletins, etc. You would make a good member. Even if you dont [sic] go for Fort Thayer is screwy enough. The address is “The Fortean Society”—444 Madison Ave., N.Y.—and ask for the first two copies of “The Fortean.”

That was from the last letter in the Museum of Innovation and Science’s archives. Why did not more survive? (Was there emote to survive?) What did Snively think of the Society as it developed? Why was he mentioned only once in the Society’s magazine? Did he drop out? None of these questions have answers.

Howard stayed with GE, dying in 1992. Donald stayed in Canton, a printer, and died early, in September 1954, just a month before his 48th birthday.