A Fortean explorer. Kind of.

Charles Steven Bristol was born 7 July 1918 in Hastings, Michigan (about 40 miles outside of Grand Rapids) to James G. Bristol and Mabel E. Slawson. The couple was well established by this time, Mabel aged 30 and James 28. They had both been born in Michigan to (almost all) Michigan natives. James was a bookcase factory supervisor, and they owned their home. They had been married just over three years by the time Charles Steven made his appearance in the world. Ten years on, they were living on the same street and James was still a supervisor at a furniture factory as well as a designer. C. Stephen, as he was called now, attended school. Their house was valued at $4,000 dollars and they owned a radio—this just as the Great Depression embraced the country.

It is not quite clear what happened to C. Steven over the course of the 1930s. In 1936, when he was about 18, the Hastings city directory listed him as a student—but I don’t know what institution he was attending. The question is pressing because in 1938, this same Steven Bristol was—according to a newspaper article—likely a student at the University of New Mexico, and was involved in labor politics—speaking at a meeting sponsored by a sawmill union to promote increased wages. The 1940 census, however, taken in April 1940, has him back in Hastings, where he was a draftsman with three years of college to his credit. (He was not captured by the census in New Mexico.) Also in 1940, he married, wedding Virginia Lois Smith on 7 September. She had just turned 17 not even two months before. C. Steven was 22.

Charles Steven Bristol was born 7 July 1918 in Hastings, Michigan (about 40 miles outside of Grand Rapids) to James G. Bristol and Mabel E. Slawson. The couple was well established by this time, Mabel aged 30 and James 28. They had both been born in Michigan to (almost all) Michigan natives. James was a bookcase factory supervisor, and they owned their home. They had been married just over three years by the time Charles Steven made his appearance in the world. Ten years on, they were living on the same street and James was still a supervisor at a furniture factory as well as a designer. C. Stephen, as he was called now, attended school. Their house was valued at $4,000 dollars and they owned a radio—this just as the Great Depression embraced the country.

It is not quite clear what happened to C. Steven over the course of the 1930s. In 1936, when he was about 18, the Hastings city directory listed him as a student—but I don’t know what institution he was attending. The question is pressing because in 1938, this same Steven Bristol was—according to a newspaper article—likely a student at the University of New Mexico, and was involved in labor politics—speaking at a meeting sponsored by a sawmill union to promote increased wages. The 1940 census, however, taken in April 1940, has him back in Hastings, where he was a draftsman with three years of college to his credit. (He was not captured by the census in New Mexico.) Also in 1940, he married, wedding Virginia Lois Smith on 7 September. She had just turned 17 not even two months before. C. Steven was 22.

At some point during the 1940s, Bristol joined the marines. I can find records of him in 1945 and 1946, stationed in San Francisco and at Camp Pendleton, near San Diego California. It seems unlikely that he joined much before 1945, since he was discharged as a private first class, but it isn’t clear, either, why he may have broke off his schooling. Perhaps it was love. If so, that would explain some changes in the middle of the decade, when the affair with Lois ran its course. Charles and Virginia were granted a divorce as of 19 January 1946. (Given the laws of the time, the proceedings likely started much earlier.) In April, he was discharged from the military. No later than March of the following year, Bristol was back in New Mexico.

Friday, 28 March 1947, Bristol married again. His wife was Jean Lucille Bucy—she went by Lucille. The newspaper announcement noted that both were seniors at the University of New Mexico, though Bristol does not seem to have been on the brink of graduating just yet. Because Lucille was a Spanish major, part of the service was done in that language. Only a few friends attended, as well as Lucille’s mother, who seems to have been separated from Lucille’s father. Neither of Bristol’s parents were noted as attendees. They took the weekend off for a honeymoon, but planned to return to classes on Monday.

Around this time, Bristol was associated with something called the “One Way Craftsman’s Guild.” I have been unable to find anything on it beyond announcements connected with Bristol. Apparently, he was national president in 1946 and 1947. According to a 1947 article in the University of New Mexico newspaper (The Lobo), the Guild was composed of writers, artists, and allied professional groups. There had been some kind of scandal in the New Mexico Chapter, with a number of people being suspended and an admitted need to more closely watch membership to keep out undesirables, but those suspended were reinstated in the summer of 1947, after Bristol’s marriage and re-election. Bristol had artistic ambitions. He displayed some of his work—as an alum—at an art show sponsored by a fraternity the following year.

Meanwhile, his eyes turned northward. In the fall of 1946, word started to spread through the press about a mysterious place in Canada’s Northwest Territory called “The Headless Valley,” presumably after a decapitated corpse found there in the early 1900s. Thanks in large part to a young journalist, Pierre Berton with the “Vancouver Sun,” who ran a series of stories on the Valley and explored the area, the world heard about the legends. The Valley was located in the Nahanni area, but was supposed to be tropical—a la Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Lost World.” There were rumors of ghosts and the mysterious deaths and disappearances of “white men.” At some point, the Valley became associated with stories about the hollow earth, that there was an entrance there—a la Jules Verne. After Burton, there were other expeditions to the area in 1947 and more press.

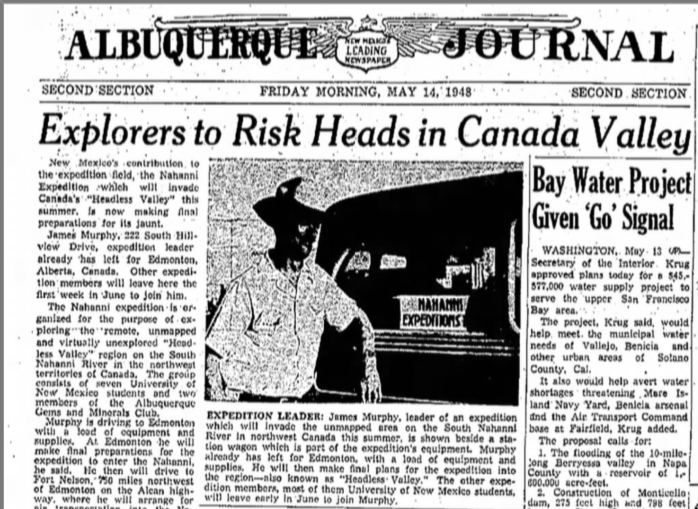

Bristol contemplated going to the area himself as early as September 1947. That same issue of “The Lobo” which contained the report on “The One Way” guild also included the following notice: “The Nahanni Valley Expedition will hold its first meeting of the year, Thursday, Oct. 2, 8:00 o’clock in Room 204 of the Ad. Building. Members will be briefed on planning developments. Transportation, equipment, food and training will also be discussed Members please attend. Visitors and all who are interested will be welcomed.” Presumably, there were more meetings, more plans. But the expedition didn’t really get rolling until spring of 1948. By this point, Bristol was no longer living in New Mexico, though the core of the group seemed to have connections to that area. And the corporation that under whose aegis the expedition took place was located in the Emerald State. Nahanni Expeditions, Inc., was established 9 March 1948, with Bristol as secretary.

That month, Bristol circulated a press release, at least among acquaintances:

“The legends of Canada’s Headless Valley are luring another group to the mysterious gorge in Northwest Canada where many of the relatively few white men to explore the area have disappeared or been killed. A group of twelve, including geologists, anthropologists, etc., many of them ex-service men, have organized Nahanni Expeditions’ Inc. at Albuquerque, New Mexico, with the intention of making many different trips of exploration. Headless Valley in the South Nahanni District of Canada has been chosen as the area for the first survey. This Valley, number one legend of the Northlands, has as its background, stories of tropical growth, hot springs, head-hunting mountain men, caves, pre-historic monsters, wailing winds and lost gold mines. Actual fact certifies the hot springs, the wailing winds, and the some person or persons who delight in lopping off prospectors heads [sic]. As for the pre-historic monsters, Indians have returned from the Nahanni country with fairly accurate drawings of mastodons burned on raw hide. The more recent history began some forty years ago when the two MacLeod brothers of Fort Simpson were found dead in the valley, reportedly decapitated. Already the Indians shunned the place because of its ‘mammoth grizzlies’ and ‘evil spirits waling in the canyons.

“Canadian police records show that Joe Mulholland of Minnesota, Bill Espeler of Winnipeg, Phil Powers and the MacLeod bothers of Ft. Simpson, Martin Jorgenson, Yukon Fischer, Annie LaFerte, O’Brien, Edwin Hall, Andy Hays, and unidentified prospector and Ernest Savard have persihed int he strange valley since 1910. In 1945 the body of Savard was found in his sleeping bag, head nearly severed from his shoulder. Savrd had previously brought rich ore samples out of the Nahanni. In 1946 Prospector John Patterson disappeared in the valley. His partner, Frank Henderson, was to have met him there, but never found him. The personnel of he expedition will fly in to the Nahanni District from Whitehorse, Canada early in June and will spend at least two months making preliminary investigations. It is possible that they will meet up with other white men, for at least one other expedition has been making plans to enter the valley.

“Members of Nahanni Expeditions’ Inc. are Robert Crawford, President, Chicago, Ill., Anthropologist and Geologist; James Murphy, Vice-President, New York City, Geologist; MFS C. Steven Bristol, Secretary, Michigan and Hawaii, Artist and Pilot; Al Torris, Secretary, Albuquerque, N.M., Geologist; Richard M. Krannawitter, Attorney, Albuquerque, N.M; Albert Bove, Brooklyn, N.Y., Geologist; Kenneth Judkins, Medina, Ohio, Geologist; Lenard Prehm, Median, Ohio, Photographer; George Sturgis, Artesia, N.M., Writer and Pilot; Robert Warner, Tucumcarri, N.M., Biologist; and Joel Wisotscky, Chicago, Ill., M.D.

“The Word ‘Nahanni’ means in Indian, ‘people over there, far away’ and was deemed a most fortunate name for the organization, as that is where its members wish to make a practice of being.”

In May, Bristol wrote to the center of Western U.S. Forteana, Don Bloch, then living in Denver. The letter was on “One Way Craftsman Guild” letterhead, and came from San Francisco. (Bristol was still president of the organization.) He used the Fortean dating system—meaning it was dated 1 June 1948, though the postmark was 24 March. for extra confusion, his return address was care-of Nahanni Expeditions, at the Alberta (Canada) Travel Bureau. This first letter was just a feeling out. He noted that Thayer had mentioned Bloch as an expert in caves, and since there would be caves in the Headless Valley, Bristol wanted to know if Bloch knew anything about them. Bloch seems to have responded that he knew nothing of the area.

Bristol replied on 11 June (that’s the postmark; his letter is undated), using the same letterhead, but the only return address being in Alberta. Bristol was much more subdued in his prospects to Bloch than he had been in the press report. He said they were “shoving off” from Edmonton in the middle of the month. He didn’t have high hopes, though: the legends, he admitted, may amount “to very little Forteana, if any,” but at least they could investigate. He was also a little worried about being part of the group, in the wildreness: being somewhat of an independent bastard, the restrictions of courtesy necessary in getting along with a group of other chaps for a period of a few months is probably going to gravel [sic] me something awful.”

According to a newspaper article written by one of the members, the expedition passed through Salt Lake City, and was poised to enter the wilderness as of 27 June. The article, by-lined Norman Thomas—not that Norman Thomas—strongly echoed the report put out by Bristol earlier in the year, and another article printed in the “Albuquerque Journal” in May, a recycling of promotions. Thomas said that they would spend the summer months making surveys with “the latest scientific methods and instruments,” while also compiling a travelogue. He recounted some of the legends, and listed members of the expedition, giving Bristol’s address as Honolulu—which may have been a mistake, or may have been one of the places Bristol lived after leaving the University. He was to be the group’s artist.

Bristol didn't make it very far, though, and the expedition didn’t amount to much, unable to break through the red tape of international travel. The expedition had failed to hire a Canadian pilot, and so brought its own airplane—but Canadian regulations did not allow the plane to cross the border. Since it was a commercial enterprise—the Expedition, after hall, had incorporated—rules required a Canadian pilot. Negotiations dragged on, and six members dropped out of the expedition, including Bristol, leaving only three members. Those who lasted eventually hired a boat and entered the valley by river. They shot 3,500 feet of film, and were happy with the scenery—but could substantiate none of the legends.

There were some hot springs, but no tropical areas of lush vegetation. The United Press sent out a wire story in August that continued to play in the press through the rest of the year, in some versions referring to the explorers as debunking a Canadian myth of Shangri-La. There were, in the way this report was edited, inconsistencies about whether the expedition ever found headless bodies—some said no, some said only skeletons—but in either case they didn’t think there was anything mysterious about the deaths. The people had succumbed to starvation or disease, and their skulls had been misplaced by natural actions—probably predators. There was at least one lecture on the excursion, but mostly it disappeared into history, overshadowed by the earlier journalistic investigation.

Afterward, Bristol moved to the Seattle area. City directories from the late 1950s and 1960 have him in Everett, Washington (about thirty minutes outside of Seattle.) I do not know what he was doing there, but it seems likely he was involved with engineering. He an Lucille had three children, all boys, James, Mark, and Morgan. At some point after 1960, the family moved to British Columbia, where Bristol took work as an Engineering Aide 2 with the district office of the British Columbia Department of Highways.

Charles Steven Bristol died 20 December 1963 at the Bulkley Valley District Hospital. He was 45.

**********

Bristol seems to have approached the Fortean Society as an extension of his expedition. He told Don Bloch, in his 11 June 1948 letter, that he was a “relative newcomer to Fortean ranks.” An, indeed, the first mention of his name in came in Doubt 20 (March 1948), when Thayer announced the formation of the Nahanni Expedition, Inc., Bristol’s role in the both the corporation and the expedition, and reprinted his press release. It was about this time, too, that he hung around with other Forteans. Bristol had come to San Francisco sometime after graduating and became associated with Chapter Two, the local Fortean organization (whose founding prompted Thayer to suggest other Forteans form into chapters.) Chapter Two had organized 1 April 1948 at the writing school of Kenneth MacNichol.

Bristol told Bloch, “Somewhat along this line, FS members in California have opened up a Chapter of the Society in San Francisco, and have occasional meetings, more or less use-ing [sic] the meditations of FM [read: MFS] Gillson Willets, with whom I recently had the pleasure of a meeting. It is an experiment which could be viewed with interest. Especially as the group is a cross representation of California’s ‘best.’” It was because he had found this group that Bristol was not entirely sympathetic to Bloch’s constant complaint that the Fortean Society should publish a membership list. He saw the positives but also “thought there are obvious reasons for not issuing such a list.” (His independent streak may have been one of them.) Besides, once he had contacted Thayer, the Fortean Society Secretary was more than happy to pass along Bloch’s address, allowing Bristol to approach him.

This chronology is a bit confused, with a lot of activity over a small span of time, making it impossible to parse the exact sequence of events. He was a member of the Society before March of 1948. He belonged to Chapter Two some time after that. He then wrote to Bloch. And all before this, he was contemplating an expedition to the Nahanni Valley. Which means, I guess, he came across Fort in the course of researching the expedition. I do not see any mentions of Fort in Pierre Berton’s articles, or the writings of anyone else, but it seems likely that someone came across Fort while researching anomalies. It bears mentioning that there was a group of marine veterans, centered in new Mexico, contemplating an expedition as early as December 1946. Bristol may have been part of that, too. If so, he had plenty of time to uncover Fort’s works.

There still seemed to be some connection between Bristol and Chapter Two in later 1948. After the expedition’s remnants returned home, some members lectured to Chapter Two at a meeting. Thayer noted the lecture in Doubt 21, December 1948, as well as Bristol’s relocation to the Seattle area. (It’s not clear if Bristol gave the lecture; he likely at least facilitated it.) “At a recent meeting, [members of Chapter Two] heard--at close range--what happened to the Nahanni Expedition to the ‘Headless Valley.’ MFS Bristol was one of the leaders of the group, which ran head-on into the Canadian Government, and came out second in the tussle. Bristol has now settled in Seattle. No reason for the official opposition to the enterprise is available, but the suggestion is that members of a party get so sore at each other, waiting for the Dominion to make up its mind, that they snap each other’s heads off. Hence the legend.”

After moving further north, Bristol remained an active member of the Fortean Society. His name appeared in ten issues of Doubt, in addition to another mention in issue 23, running until June 1957 (Doubt 54). In many of those issues, his name appeared more than once. He was most active in the early 1950s, 1951 and 1952, slowing down as the decade continued. There’s a suggestion he may have just become very busy, as at least once he sent in data he had been compiling for a while, making it old but still interesting. Nonetheless, he continued, while many other Forteans who had come to the Society in the 1940s dropped out.

The bulk of his data show Bristol to have been concerned with mainstream Fortean phenomena. He sent in material on mysterious explosions and loud bangs (Doubt 23, 30, 32); miasmatic smells and odd fogs (32); strange rains (30, 32); cryptozoological matters such as unidentified animals washed ashore (Doubt 29) and sightings of unknown creatures (30), red tides, mysterious bird and fish deaths, a baboon clubbed and shot in Illinois (all Doubt 31), birds that lit a tree on fire while playing with matches and a pigeon seen wearing pince-nez glasses (Doubt 45); flying saucers (30, 31) and associate phenomena, including a sun that blazed blue over Egypt, dust storms in the upper atmosphere where no dust was supposed to be seen, and a “star” that traced small circles in the night sky above Seattle (31); as well as other, harder to classify anomalies, such as a mysterious pillar of fire seen in Alaska, a self-filling water-barrel in the Ozarks (both 31), the then-current paranoia over nylons disappearing from the legs of women (32), and a mother-daughter pair (though the story could not explain how it knew the women were related) who randomly attacked and bit a man in South Carolina (45). He had some interest in Wild Talents, too, asking in one letter that Thayer published (also 31),

“‘Has anyone checked to see whether blind and/or mute people have--as a group--over ordinary mortals--any extra dimensional perceptions that follow a basic pattern?”

A fair number of times Thayer mentioned Bristol, it was in regard to material that could not be used, or was a generic credit untethered to any particular clipping. But that didn’t mean the two didn’t share a sensibility beyond a general interest in Fortean anomalies. Twice Bristol was in the running for Thayer’s mock “first place prize,” referring to the best material sent in during any period. (He received third place each time.) More pointedly, Bristol shared Thayer’s distrust for experts and particularly for those of a religious persuasion. Doubt 32 showcased an article he sent in about the Idaho State Treasurer going personally bankrupt. (Thayer pointed out that the article was so poorly written it was impossible to even tell who the treasurer was.) Doubt 42 had stories he contributed about a man in England mauled because he did not observe the two minutes of silence honoring the dead King George VI and rumors that Tule Lake was being converted into a detention camp for subversives. (It’s hard to tell, but he may also have contributed a story that voiced concern the government was giving job to foreign companies.) His last contribution was about an Australian dental surgeon who said that kids’s teeth could be strengthened by limiting exposure to bright electric lights . . . and horror shows on the radio. (That may have gone to Thayer’s dislike of fluoridated water, but it also made the surgeon sound ridiculous.)

The final three bits of material that Bristol contributed all poked fun at religion. For Doubt 29, he contributed an article about a Women’s Christian Temperance Union member who said she was not against contraceptives but their “promiscuous sale” in slot machines “where anybody, including children, can buy them.” Thayer did not drag out the joke, but the clear question was, What’s it matter if a five year old buys a condom? The other two were not even that hard to parse. Doubt 30 discussed a piece Bristol sent in about a preacher charged with murder in Tennessee for drowning a girl by holding her under water too long during a baptism. He was the girl’s grandfather. In Doubt 32, appeared mention of a clipping sent in by Bristol about “The Children of Light” (associated with the “Church of God,” a break-off groups of the Pentecostals) who predicted the end of the world for 23 December 1950.

The upshot of all this material is that Bristol seems to have come to Forteanism through a very specific mechanism, and then settled in, becoming fascinated by Forteanism more generally, its investigation of anomalies, its consideration of Wild Talents, and its critique of the press. He also seems to have enjoyed the anti-authoritarian stance that was present in Fort and enhanced by Thayer. (This position would fit with his estimation of himself as an independent bastard.) He was skeptical of authority, whether it was secular, scientific, or religious. And this skepticism was enough to keep him attached to the Fortean Society for more than a decade, long after the disappointment of the expedition that had initially led him to the subject.

Friday, 28 March 1947, Bristol married again. His wife was Jean Lucille Bucy—she went by Lucille. The newspaper announcement noted that both were seniors at the University of New Mexico, though Bristol does not seem to have been on the brink of graduating just yet. Because Lucille was a Spanish major, part of the service was done in that language. Only a few friends attended, as well as Lucille’s mother, who seems to have been separated from Lucille’s father. Neither of Bristol’s parents were noted as attendees. They took the weekend off for a honeymoon, but planned to return to classes on Monday.

Around this time, Bristol was associated with something called the “One Way Craftsman’s Guild.” I have been unable to find anything on it beyond announcements connected with Bristol. Apparently, he was national president in 1946 and 1947. According to a 1947 article in the University of New Mexico newspaper (The Lobo), the Guild was composed of writers, artists, and allied professional groups. There had been some kind of scandal in the New Mexico Chapter, with a number of people being suspended and an admitted need to more closely watch membership to keep out undesirables, but those suspended were reinstated in the summer of 1947, after Bristol’s marriage and re-election. Bristol had artistic ambitions. He displayed some of his work—as an alum—at an art show sponsored by a fraternity the following year.

Meanwhile, his eyes turned northward. In the fall of 1946, word started to spread through the press about a mysterious place in Canada’s Northwest Territory called “The Headless Valley,” presumably after a decapitated corpse found there in the early 1900s. Thanks in large part to a young journalist, Pierre Berton with the “Vancouver Sun,” who ran a series of stories on the Valley and explored the area, the world heard about the legends. The Valley was located in the Nahanni area, but was supposed to be tropical—a la Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Lost World.” There were rumors of ghosts and the mysterious deaths and disappearances of “white men.” At some point, the Valley became associated with stories about the hollow earth, that there was an entrance there—a la Jules Verne. After Burton, there were other expeditions to the area in 1947 and more press.

Bristol contemplated going to the area himself as early as September 1947. That same issue of “The Lobo” which contained the report on “The One Way” guild also included the following notice: “The Nahanni Valley Expedition will hold its first meeting of the year, Thursday, Oct. 2, 8:00 o’clock in Room 204 of the Ad. Building. Members will be briefed on planning developments. Transportation, equipment, food and training will also be discussed Members please attend. Visitors and all who are interested will be welcomed.” Presumably, there were more meetings, more plans. But the expedition didn’t really get rolling until spring of 1948. By this point, Bristol was no longer living in New Mexico, though the core of the group seemed to have connections to that area. And the corporation that under whose aegis the expedition took place was located in the Emerald State. Nahanni Expeditions, Inc., was established 9 March 1948, with Bristol as secretary.

That month, Bristol circulated a press release, at least among acquaintances:

“The legends of Canada’s Headless Valley are luring another group to the mysterious gorge in Northwest Canada where many of the relatively few white men to explore the area have disappeared or been killed. A group of twelve, including geologists, anthropologists, etc., many of them ex-service men, have organized Nahanni Expeditions’ Inc. at Albuquerque, New Mexico, with the intention of making many different trips of exploration. Headless Valley in the South Nahanni District of Canada has been chosen as the area for the first survey. This Valley, number one legend of the Northlands, has as its background, stories of tropical growth, hot springs, head-hunting mountain men, caves, pre-historic monsters, wailing winds and lost gold mines. Actual fact certifies the hot springs, the wailing winds, and the some person or persons who delight in lopping off prospectors heads [sic]. As for the pre-historic monsters, Indians have returned from the Nahanni country with fairly accurate drawings of mastodons burned on raw hide. The more recent history began some forty years ago when the two MacLeod brothers of Fort Simpson were found dead in the valley, reportedly decapitated. Already the Indians shunned the place because of its ‘mammoth grizzlies’ and ‘evil spirits waling in the canyons.

“Canadian police records show that Joe Mulholland of Minnesota, Bill Espeler of Winnipeg, Phil Powers and the MacLeod bothers of Ft. Simpson, Martin Jorgenson, Yukon Fischer, Annie LaFerte, O’Brien, Edwin Hall, Andy Hays, and unidentified prospector and Ernest Savard have persihed int he strange valley since 1910. In 1945 the body of Savard was found in his sleeping bag, head nearly severed from his shoulder. Savrd had previously brought rich ore samples out of the Nahanni. In 1946 Prospector John Patterson disappeared in the valley. His partner, Frank Henderson, was to have met him there, but never found him. The personnel of he expedition will fly in to the Nahanni District from Whitehorse, Canada early in June and will spend at least two months making preliminary investigations. It is possible that they will meet up with other white men, for at least one other expedition has been making plans to enter the valley.

“Members of Nahanni Expeditions’ Inc. are Robert Crawford, President, Chicago, Ill., Anthropologist and Geologist; James Murphy, Vice-President, New York City, Geologist; MFS C. Steven Bristol, Secretary, Michigan and Hawaii, Artist and Pilot; Al Torris, Secretary, Albuquerque, N.M., Geologist; Richard M. Krannawitter, Attorney, Albuquerque, N.M; Albert Bove, Brooklyn, N.Y., Geologist; Kenneth Judkins, Medina, Ohio, Geologist; Lenard Prehm, Median, Ohio, Photographer; George Sturgis, Artesia, N.M., Writer and Pilot; Robert Warner, Tucumcarri, N.M., Biologist; and Joel Wisotscky, Chicago, Ill., M.D.

“The Word ‘Nahanni’ means in Indian, ‘people over there, far away’ and was deemed a most fortunate name for the organization, as that is where its members wish to make a practice of being.”

In May, Bristol wrote to the center of Western U.S. Forteana, Don Bloch, then living in Denver. The letter was on “One Way Craftsman Guild” letterhead, and came from San Francisco. (Bristol was still president of the organization.) He used the Fortean dating system—meaning it was dated 1 June 1948, though the postmark was 24 March. for extra confusion, his return address was care-of Nahanni Expeditions, at the Alberta (Canada) Travel Bureau. This first letter was just a feeling out. He noted that Thayer had mentioned Bloch as an expert in caves, and since there would be caves in the Headless Valley, Bristol wanted to know if Bloch knew anything about them. Bloch seems to have responded that he knew nothing of the area.

Bristol replied on 11 June (that’s the postmark; his letter is undated), using the same letterhead, but the only return address being in Alberta. Bristol was much more subdued in his prospects to Bloch than he had been in the press report. He said they were “shoving off” from Edmonton in the middle of the month. He didn’t have high hopes, though: the legends, he admitted, may amount “to very little Forteana, if any,” but at least they could investigate. He was also a little worried about being part of the group, in the wildreness: being somewhat of an independent bastard, the restrictions of courtesy necessary in getting along with a group of other chaps for a period of a few months is probably going to gravel [sic] me something awful.”

According to a newspaper article written by one of the members, the expedition passed through Salt Lake City, and was poised to enter the wilderness as of 27 June. The article, by-lined Norman Thomas—not that Norman Thomas—strongly echoed the report put out by Bristol earlier in the year, and another article printed in the “Albuquerque Journal” in May, a recycling of promotions. Thomas said that they would spend the summer months making surveys with “the latest scientific methods and instruments,” while also compiling a travelogue. He recounted some of the legends, and listed members of the expedition, giving Bristol’s address as Honolulu—which may have been a mistake, or may have been one of the places Bristol lived after leaving the University. He was to be the group’s artist.

Bristol didn't make it very far, though, and the expedition didn’t amount to much, unable to break through the red tape of international travel. The expedition had failed to hire a Canadian pilot, and so brought its own airplane—but Canadian regulations did not allow the plane to cross the border. Since it was a commercial enterprise—the Expedition, after hall, had incorporated—rules required a Canadian pilot. Negotiations dragged on, and six members dropped out of the expedition, including Bristol, leaving only three members. Those who lasted eventually hired a boat and entered the valley by river. They shot 3,500 feet of film, and were happy with the scenery—but could substantiate none of the legends.

There were some hot springs, but no tropical areas of lush vegetation. The United Press sent out a wire story in August that continued to play in the press through the rest of the year, in some versions referring to the explorers as debunking a Canadian myth of Shangri-La. There were, in the way this report was edited, inconsistencies about whether the expedition ever found headless bodies—some said no, some said only skeletons—but in either case they didn’t think there was anything mysterious about the deaths. The people had succumbed to starvation or disease, and their skulls had been misplaced by natural actions—probably predators. There was at least one lecture on the excursion, but mostly it disappeared into history, overshadowed by the earlier journalistic investigation.

Afterward, Bristol moved to the Seattle area. City directories from the late 1950s and 1960 have him in Everett, Washington (about thirty minutes outside of Seattle.) I do not know what he was doing there, but it seems likely he was involved with engineering. He an Lucille had three children, all boys, James, Mark, and Morgan. At some point after 1960, the family moved to British Columbia, where Bristol took work as an Engineering Aide 2 with the district office of the British Columbia Department of Highways.

Charles Steven Bristol died 20 December 1963 at the Bulkley Valley District Hospital. He was 45.

**********

Bristol seems to have approached the Fortean Society as an extension of his expedition. He told Don Bloch, in his 11 June 1948 letter, that he was a “relative newcomer to Fortean ranks.” An, indeed, the first mention of his name in came in Doubt 20 (March 1948), when Thayer announced the formation of the Nahanni Expedition, Inc., Bristol’s role in the both the corporation and the expedition, and reprinted his press release. It was about this time, too, that he hung around with other Forteans. Bristol had come to San Francisco sometime after graduating and became associated with Chapter Two, the local Fortean organization (whose founding prompted Thayer to suggest other Forteans form into chapters.) Chapter Two had organized 1 April 1948 at the writing school of Kenneth MacNichol.

Bristol told Bloch, “Somewhat along this line, FS members in California have opened up a Chapter of the Society in San Francisco, and have occasional meetings, more or less use-ing [sic] the meditations of FM [read: MFS] Gillson Willets, with whom I recently had the pleasure of a meeting. It is an experiment which could be viewed with interest. Especially as the group is a cross representation of California’s ‘best.’” It was because he had found this group that Bristol was not entirely sympathetic to Bloch’s constant complaint that the Fortean Society should publish a membership list. He saw the positives but also “thought there are obvious reasons for not issuing such a list.” (His independent streak may have been one of them.) Besides, once he had contacted Thayer, the Fortean Society Secretary was more than happy to pass along Bloch’s address, allowing Bristol to approach him.

This chronology is a bit confused, with a lot of activity over a small span of time, making it impossible to parse the exact sequence of events. He was a member of the Society before March of 1948. He belonged to Chapter Two some time after that. He then wrote to Bloch. And all before this, he was contemplating an expedition to the Nahanni Valley. Which means, I guess, he came across Fort in the course of researching the expedition. I do not see any mentions of Fort in Pierre Berton’s articles, or the writings of anyone else, but it seems likely that someone came across Fort while researching anomalies. It bears mentioning that there was a group of marine veterans, centered in new Mexico, contemplating an expedition as early as December 1946. Bristol may have been part of that, too. If so, he had plenty of time to uncover Fort’s works.

There still seemed to be some connection between Bristol and Chapter Two in later 1948. After the expedition’s remnants returned home, some members lectured to Chapter Two at a meeting. Thayer noted the lecture in Doubt 21, December 1948, as well as Bristol’s relocation to the Seattle area. (It’s not clear if Bristol gave the lecture; he likely at least facilitated it.) “At a recent meeting, [members of Chapter Two] heard--at close range--what happened to the Nahanni Expedition to the ‘Headless Valley.’ MFS Bristol was one of the leaders of the group, which ran head-on into the Canadian Government, and came out second in the tussle. Bristol has now settled in Seattle. No reason for the official opposition to the enterprise is available, but the suggestion is that members of a party get so sore at each other, waiting for the Dominion to make up its mind, that they snap each other’s heads off. Hence the legend.”

After moving further north, Bristol remained an active member of the Fortean Society. His name appeared in ten issues of Doubt, in addition to another mention in issue 23, running until June 1957 (Doubt 54). In many of those issues, his name appeared more than once. He was most active in the early 1950s, 1951 and 1952, slowing down as the decade continued. There’s a suggestion he may have just become very busy, as at least once he sent in data he had been compiling for a while, making it old but still interesting. Nonetheless, he continued, while many other Forteans who had come to the Society in the 1940s dropped out.

The bulk of his data show Bristol to have been concerned with mainstream Fortean phenomena. He sent in material on mysterious explosions and loud bangs (Doubt 23, 30, 32); miasmatic smells and odd fogs (32); strange rains (30, 32); cryptozoological matters such as unidentified animals washed ashore (Doubt 29) and sightings of unknown creatures (30), red tides, mysterious bird and fish deaths, a baboon clubbed and shot in Illinois (all Doubt 31), birds that lit a tree on fire while playing with matches and a pigeon seen wearing pince-nez glasses (Doubt 45); flying saucers (30, 31) and associate phenomena, including a sun that blazed blue over Egypt, dust storms in the upper atmosphere where no dust was supposed to be seen, and a “star” that traced small circles in the night sky above Seattle (31); as well as other, harder to classify anomalies, such as a mysterious pillar of fire seen in Alaska, a self-filling water-barrel in the Ozarks (both 31), the then-current paranoia over nylons disappearing from the legs of women (32), and a mother-daughter pair (though the story could not explain how it knew the women were related) who randomly attacked and bit a man in South Carolina (45). He had some interest in Wild Talents, too, asking in one letter that Thayer published (also 31),

“‘Has anyone checked to see whether blind and/or mute people have--as a group--over ordinary mortals--any extra dimensional perceptions that follow a basic pattern?”

A fair number of times Thayer mentioned Bristol, it was in regard to material that could not be used, or was a generic credit untethered to any particular clipping. But that didn’t mean the two didn’t share a sensibility beyond a general interest in Fortean anomalies. Twice Bristol was in the running for Thayer’s mock “first place prize,” referring to the best material sent in during any period. (He received third place each time.) More pointedly, Bristol shared Thayer’s distrust for experts and particularly for those of a religious persuasion. Doubt 32 showcased an article he sent in about the Idaho State Treasurer going personally bankrupt. (Thayer pointed out that the article was so poorly written it was impossible to even tell who the treasurer was.) Doubt 42 had stories he contributed about a man in England mauled because he did not observe the two minutes of silence honoring the dead King George VI and rumors that Tule Lake was being converted into a detention camp for subversives. (It’s hard to tell, but he may also have contributed a story that voiced concern the government was giving job to foreign companies.) His last contribution was about an Australian dental surgeon who said that kids’s teeth could be strengthened by limiting exposure to bright electric lights . . . and horror shows on the radio. (That may have gone to Thayer’s dislike of fluoridated water, but it also made the surgeon sound ridiculous.)

The final three bits of material that Bristol contributed all poked fun at religion. For Doubt 29, he contributed an article about a Women’s Christian Temperance Union member who said she was not against contraceptives but their “promiscuous sale” in slot machines “where anybody, including children, can buy them.” Thayer did not drag out the joke, but the clear question was, What’s it matter if a five year old buys a condom? The other two were not even that hard to parse. Doubt 30 discussed a piece Bristol sent in about a preacher charged with murder in Tennessee for drowning a girl by holding her under water too long during a baptism. He was the girl’s grandfather. In Doubt 32, appeared mention of a clipping sent in by Bristol about “The Children of Light” (associated with the “Church of God,” a break-off groups of the Pentecostals) who predicted the end of the world for 23 December 1950.

The upshot of all this material is that Bristol seems to have come to Forteanism through a very specific mechanism, and then settled in, becoming fascinated by Forteanism more generally, its investigation of anomalies, its consideration of Wild Talents, and its critique of the press. He also seems to have enjoyed the anti-authoritarian stance that was present in Fort and enhanced by Thayer. (This position would fit with his estimation of himself as an independent bastard.) He was skeptical of authority, whether it was secular, scientific, or religious. And this skepticism was enough to keep him attached to the Fortean Society for more than a decade, long after the disappointment of the expedition that had initially led him to the subject.