Sorting out the early history of Charles Dilks is too complicated, given that the name was surprisingly common in the New York, New Jersey area. From his one mention in The Fortean Society Magazine (10, Autumn 1944), we know that he was a civil engineer. And indeed, there was a Charles F. Dilks living in Brooklyn in 1930, married to a Mary Dilks. He had been born in New Jersey around 1888. (There seems to have been another Charles Dilks, also born in New Jersey, also around the same time, who was married to a Bertha Dilks and had four children. Their early records are, for my purposes, hopelessly entangled.) This Dilks was an acoustical engineer, which is close enough for historical work.

The Brooklyn Daily Star has a Charles F. Dilks awarded twelve patents for an acoustic diaphragm (“North Queens Inventors Get Patent Rights,” 9 February 1933, p. 5). City directories for Ithaca, NY list a Mary and Charles F. Dilks in that city for 1937 and 1938, with Charles employed as a consulting engineer for The Scientific Instrument Company. According to the 1940 census, they had returned to Kings County in New York by 1940 (and had lived there as late as 1935), where Charles worked as a foreman at a machine company. It is worth noting that Dilks—like that other engineering Fortean, Frederick Hehr—was mostly self-taught, or taught on the job, having only an eighth-grade education, which was increasingly rare in the engineering world by this time. (Mary, his junior by a decade, had a year of college under her belt.)

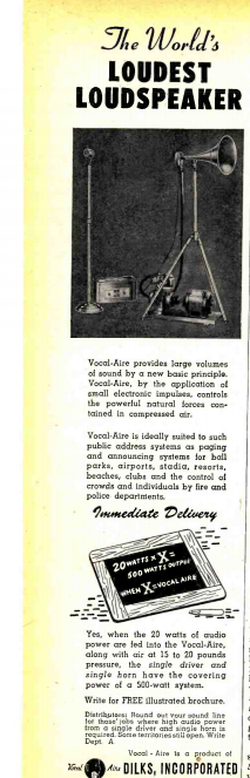

By 1941, the Dilkses moved to Norwalk, Connecticut, and looked to cash in on his acoustical inventions. He submitted a patent on 4 September 1945, and formed a partnership with Thomas A. Collins, Raymond Meyers, (and, possibly, Lucy C. Tammany), out of which arrangement came the Dilks Vocal-Aire loudspeaker and company. The partners claimed it was the loudest speaker on the market, unique because it operated on the same principles as the human vocal cords. Granting some legitimacy to this claim, Dilks was awarded another patent on his device (#2384371). The company advertised in the likes of Radio News (December 1946, page 134), gained notice in The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America [vol 18 (1946): 236] and received a glowing write-up in Popular Science [William P. Vogel, Jr., The Horn That Shouts Like a Man, Popular Science, July 1948, 129-131]:

“For 50 years researchers trying to devise ways of modulating an air column directly were unable to overcome high distortion and the difficulty of relieving excess air pressure . . . [But] just before the war . . . Charles F. Dilks licked distortion by the design, size, and shape of the grids. He then solved the pressure problem with a delicate pressure compensator that was controlled by the dissension of a diaphragm built into the housing of the voice box.

“Before his patents were issued, Dilks used to cut the grids secretly, in a locked room, with a special lathe and a handmade saw consisting of 40 small circular toothed blades, of precisely graduated sizes, set along a spindle. Grids can now be cut more publicly, but the tolerances must be just as fine as in Dilk’s early models.”

The problem, for Dilks, was he did not get to bask in this glory. According to the Norwalk, CT, city directory, he died on Christmas Day, 1945, leaving Mary a widow. His company was reorganized in the fall of 1947, with the chief engineer and factory superintendent buying some of the assets and patents and setting up a rival company. The fate of the company is not known to me.

But it wasn’t his new device that was the source of the attraction between Dilks and the Fortean Society. Rather, it was a short book—a pamphlet, really--that he self published in 1941. The full title was “Recognition of Fundamental Error as a Basis of Reform in Physics of Practical Sciences/We Must Return to Practical Things.” The only copy I know of is held at the New York Public Library, where it is catalogued under the name “Has Our Education System Out-Lived Its Usefulness? We Must Return to Practical Things” [OCLC: 42033277; Call Number SB p.v. 755]. I have not seen it. The sixteen page document may shed some light on Dilks’s biography. Certainly it would explain his ideas.

Instead, all I have is Thayer’s gloss, given on page 142 of number 10 of his magazine, under the title “Watts Per Hour.” Thayer gestures toward Dilks’s intentions, but does not bother with the detail:

“A new type of criticism of so-called ‘exact sciences’ and of their effect upon our everyday life is advanced by MFS Charles F. Dilks, C.E.”

“Mr. Dilks founds his philosophy upon a series of glaring ‘discrepancies in formula and text’ which he has discovered in standard instruction books, chiefly electrical . . . [ellipse in original] Your embattled Sectretary is no wise able to cope with mathematical criticism of this kind, but if he understands Mr. Dilks, the charge is that we are all paying electric light and power companies at least 3600 times as much money as they have coming, and to nip in the bud any revolt against the practice, the public utilities have insinuated the prejudice supporting the error into our school texts. We are taught to think about watts and watt-hours in a certain way so that we grow up never questioning our light bills.

“There is much more to it than that, but the members are urged to look ingot he matter for themselves. A limited number of the tracts are available for 20 cents each. The title is: ‘Recognition of Fundamental Error as a Basis of Reform in Physics of Practical Sciences/We Must Return to Practical Things/by Charles F. Dilks, C.E./Author-Engineer—Educator.’

“In ordering, just say—‘send Dilks.’ The book is 11 sheets, one side-mimeograph matter, with one cover. The price—20 cents—which is less than the cost of production.”

How long Dilks had been a member, and how he had stumbled across Fort or the Fortean Society is unknown. His attraction to Thayer is obvious, what with his having found faults in the formulas of physicists. Dilks must’ve at least accepted Thayer’s invitation to join, to get that MFS by his name. That he contributed so little may be from lack of interest. But it’s also the case that he died just over a year after his name first appeared in Thayer’s rag.

And so Dilks’s Forteanism is a mystery.

[Edited for multiple grammar mistakes.]