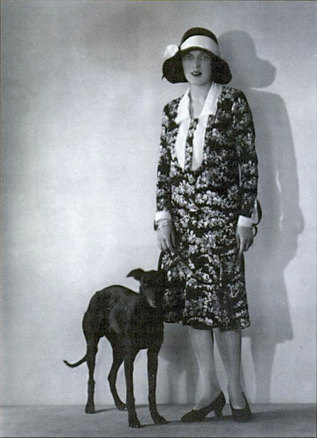

Crosby, in the 1920s, with her dog Clytoris.

Crosby, in the 1920s, with her dog Clytoris. A once formidable patron of modernism, and later peace advocate—now a forgotten Fortean.

Caresse Crosby is no longer remembered well, but there is an abundance of material on her life, including autobiographies and biographies. And so this entry will be relatively brief. Mary Phelps Jacobs—known as Polly—was born to a prominent Boston family on 20 April 1891, and, as her biographer Linda Hamalian notes, never lost her aristocratic edge. She is probably best known now as the inventor of the modern bra. She had a brief marriage, and two children, with Richard Rogers Peabody, scion of another Boston family; he was not interested in domestic life, though, and suffered from alcoholism, made worse by his turn in World War I. While still married, Polly was asked to chaperone another World War I vet, Harry Crosby. The two fell into an affair. Later, Polly divorced Richard and married Harry.

Shortly after their marriage, the new family left for Paris, where they lived an extravagantly debauched lifestyle. Harry was not interested in children, and so they were soon enough shipped off to boarding schools. Meanwhile, Polly adopted a new name—Caresse. Cares and Harry drank a lot, took drugs, engaged in orgies, slept with barely-teenaged girls, and threw outrageous parties. They had multiple affairs. Harry was related to J.P. Morgan—yes, that J.P. Morgan—and his family kept him and Caresse flush with funds. Their home was frequented by a steady stream of ex-patriates.

Caresse Crosby is no longer remembered well, but there is an abundance of material on her life, including autobiographies and biographies. And so this entry will be relatively brief. Mary Phelps Jacobs—known as Polly—was born to a prominent Boston family on 20 April 1891, and, as her biographer Linda Hamalian notes, never lost her aristocratic edge. She is probably best known now as the inventor of the modern bra. She had a brief marriage, and two children, with Richard Rogers Peabody, scion of another Boston family; he was not interested in domestic life, though, and suffered from alcoholism, made worse by his turn in World War I. While still married, Polly was asked to chaperone another World War I vet, Harry Crosby. The two fell into an affair. Later, Polly divorced Richard and married Harry.

Shortly after their marriage, the new family left for Paris, where they lived an extravagantly debauched lifestyle. Harry was not interested in children, and so they were soon enough shipped off to boarding schools. Meanwhile, Polly adopted a new name—Caresse. Cares and Harry drank a lot, took drugs, engaged in orgies, slept with barely-teenaged girls, and threw outrageous parties. They had multiple affairs. Harry was related to J.P. Morgan—yes, that J.P. Morgan—and his family kept him and Caresse flush with funds. Their home was frequented by a steady stream of ex-patriates.

In 1927, they formed a book publishing company that would later be renamed Black Sun Press. It put out small, beautiful editions of their own poetry, and also of modernist writers and artists, Joyce and Hemingway and others. Badly scarred by World War I, where he served as an ambulance driver, Harry was in love with death; he and Caresse had made a suicide pact for a day in the early 1940s that had astrological significance. But Harry fell in love with someone else and, in 1929, after a tryst, he killed his mistress and then himself. Caresse was crushed. But she continued in Europe, putting out books, and supported by Crosby and her own family, until she was driven out by the Nazis. She had subsequent affairs, and even another (brief) marriage.

Relocated to Virginia, Crosby remained a patron of modernist literature, supporting, among others, Henry Miller. In the early 1940s, she opened a modern art gallery in Washington, D.C., and started a magazine, “Portfolio.” It ran six issues, publishing avant-garde writers, before folding. Crosby had written some poetry in her earlier years, but really didn’t consider herself an artist—she was not unlike James Laughlin in that regard, a dabbler in the arts who made her mark as a patron. But in 1953, she published her autobiography, “The Passionate Years.” In 1955, her son died in an automobile crash.

By this time, Crosby had become involved in politics. Living in Rome, but traveling frequently to the U.S., she was a dedicated peace activist. (Seeing two husbands psychically destroyed by war may have contributed.) Like Clara Studer and Garry Davis—fellow Forteans; Studer an acquaintance and fellow ex-pat in Italy—she also advocated for the dissolution of national boundaries and world citizenship. In the 1950s, she tried to establish a base of operations in Greece, but the movement fell apart.

Caresse Crosby died 24 January 1970, aged 78, in Rome, Italy.

***************

The first connections between Caresse Crosby and the Fortean Society are not as easy to trace as those between the Studers and the Society, but they seem to have grown out of the same network: Ezra Pound was a node. Somewhat surprisingly, for all that Crosby was fairly well known in the 1940s and 1950s—not a much as in the 1920s, neither was she as obscure as when she died—Crosby seems to have been genuinely involved with the Fortean Society: a friend of Tiffany Thayer, primarily, but also interested in the political dissent that he published in Doubt.

The earliest connection I can find between the Society and Crosby is the March of 1950, when Thayer wrote to her. (The letter is preserved in her papers at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.) It was a brief note, care of Crosby at the Black Sun Press—which would see its end that year—in Washington, D.C: “We must have met somewhere, but I don’t think it was in Paris. I was there in ’30 but met only dragomen (some nice ones). Do you sometimes get out to the hospital to see Ezra?” It’s a fairly cryptic message, made the more so by the lack of any preserved response. Nonetheless, Thayer’s introduction shows that he and Caresse ran in some of the same circles, and the center of the Venn Diagram was Ezra Pound. There would have been other connections, too—Henry Miller, for example.

Crosby seems to have responded positively to Thayer, and was mentioned in Doubt a year later—issue 31, March 1951. She was among a number of people who contributed a story about a girl in Kansas who had to undergo surgery—because a sunflower grew in her lungs. The girl was two; the sunflower half an inch long. The story was carried on the U.P. wires. It is, of course, possible that the story was sent in by someone else with the surname Crosby, but I have seen no reference to any other Crosby in Doubt, so do not think so. Apparently, Thayer’s (re)opening gambit got her to join as a member.

The connection seemed to be stronger than mere membership, though. Thayer had long nursed a hope to return to Europe, and his plans evolved to fit a meeting with her onto his itinerary. He mentioned to Eric Frank Russell in June 1951 that he would go to Rome and see her at her castle, which was called “Free World.” (By this point, Thayer had spent about half-a-decade researching and writing a novel on the Mona Lisa, and so had developed quite the fondness for Italy.) As it turned out, Thayer did not make the trip until 1952, and through some kind of mis-communication, he missed meeting with her.

Thayer did manage a meeting in March of 1953, though—Thayer told Russell he had dinner with her. The correspondence is not perfectly clear, but it seems as though she also engaged him to do some publicity for her—he was, after all, in public relations. From what I can gather, Thayer wrote an article about Crosby and her world citizenry movement for “The American Weekly.” He was also helping promote her book “The Passionate Years,” pushing it hard in issue 41 (July 1953). She told him, “I am thrilled that you will do something more on it too. I don’t expect I can outsell Mr. Kinsey but I would like to outstrip Bing [Crosby, who had published his memoir].”

For his part, Thayer was impressed by the autobiography. He wrote about it in Doubt 42 (October 1953): “We were so crowded for space last issue that we did not give MFS Crosby’s autobiography as much praise as it deserves. Besides the interest of the subject matter and the intimate view of the arts of the period, it is a writing feat which professionals will enjoy for technical reasons, The style is unique and engaging. You think you are looking at a nose-gay of rosebuds, surrounded by the tulle or rumpled lace panties, only to discover—suddenly—that there’s a rapier in the heart of it.”

He also tipped his hat to Crosby and her associates for all the obvious hard work that had gone into their efforts advocating for world citizenship. But he was not ready to sign on: “being an anarchist I don’t believe in any government at all, and so cannot subscribe to [Hugh J.] Schofield’s Constitution or sign up as a member.” Still, “eager to help spread the concept of World Citizenship and to help others find their way to participation.” He could not believe how disorganized Crosby was, despite the work she was putting into the movement. The article for “American Weekly” was falling apart because her assistants could not get material to him in a timely manner, and none of her associates seemed equipped to deal with the good publicity that would come from the article.

Thayer thought that “lime most idealists,” Crosby lacked “any sense of organization. . . . What is the sense of stirring up excitement in the American Weekly or anywhere else if nobody is prepared to sign up the applicants.” No one even had the address of Hugh J. Schonfield, the lawyer who was one of the central hubs in the push for creating new, peaceful sovereign nation of world citizens. “Lordy, lady. You can’t do business that way. . . . Somebody in the USA must be equipped with a supply of ‘literature’, a roster of the enrolled, application blanks, pins and buttons and what not all.” He was tempted to take on the job himself, but his convictions prevented it. Lest she worry that he was upset, Thayer added, “Don’t think I am ill tempered or crochet. It is just that I have enough business-man in me to appreciate that radicals, artists and idealists have to be efficient to get anywhere.”

It was that businessman in him that also encouraged her to roll with the current publicity for “The Passionate Years,” though she might not like it: “Dial’s ad was meant to see books, no matter how. I am afraid that—the public being what it is—the only way to get sensational volume is by being sensational. I quite understand your reaction, but one cannot be in good taste and ‘popular’ at the same time.” It was a creed Thayer had lived by himself, accepting the poor judgment of critics and attacks on him as déclassé in order to sell books.

Crosby appreciated Thayer’s help. After missing meeting each other again in 1954, she insisted that they needed to get together to talk. And then in 1957, after several more missed engagements—and a couple made—she wrote, “I miss your wisdom and counsel so very much, especially now when greater problems than ever have arisen and World Citizens in many countries look to me for decisions.” And she helped to spread word of the Fortean Society and Doubt among her circle. In 1953, she subscribed to the magazine for Charles Olson, the poet (who would use some Fortean themes in his work); Andre Magnus, a public relations executive in the French film industry; and Edward Durrell Stone, the architect. (Olson was at North Carolina’s Back Mountain College, and Thayer started getting that experimental school’s reviews again, which he liked better than earlier numbers.) She also handed out issues of Doubt to friends, acquaintances, and people with whom she was doing business.

In the end, Crosby was sanguine about the article for American Weekly falling through, since her efforts had a setback at just that moment. In 1942, she had purchased a house in Delphi, Greece; a decade later, she was trying to make that the center of her world citizenship activism. She went to visit in October 1952 and was arrested by Greek police as a threat to the economy and politics of the country. There were various machinations in court, and Crosby tried to establish her center in Cyprus, instead, but the Greek government had its way. The Cyprus center was to be housed in a geodesic dome designed by R. Buckminster Fuller, another Fortean.

Thayer kept up a steady commentary on her efforts. Issue 41 of Doubt (July 1953) had as its cover the symbol of the World Citizens movement emblazoned on an announcement that Crosby had given to Thayer—Pietro Lazzari’s sculptures were on sale to raise money for an “Artists’ Delphic Fund.” A three-column essay on the movement then led off the issue. The piece started, “Not every Fortean will recognize himself as the hub, spokes and motive power of the world, as pictured on our cover, but that is what the design is getting at, as I understand it.

“The individual is the all important unit. Each is his own universe, Living is the chiefest of the arts, and the aim of the organization which has nailed this new Jolly Roger to its masthead is to see that the opportunity is not lacking anywhere on Earth for individuals to realize their fullest creative potentials. as universe builders and movers.

“The design is the symbol of the World Citizens movement, which claims a registration of about 600,000, and more coming in all the time. It was given to me by MFS Caresse Crosby just before she took off for Delphi, Greece.”

Crosby had left for Delphi to dedicate a footprint—and the soil on which it was impressed—to the movement. But Thayer had not yet heard the results of her attempt. This spot was to be a sovereign plot for the world citizen movement, belonging to no country. She hoped that there would be similar footprints around the world, until borders were perforated, and nations porous. “The National pattern is outmoded,” Thayer quoted her as saying. “National leaders have failed us. It is for man the world citizen to mould a future nearer to the heart’s desire.” He then went on to note ways Forteans could help—money, of course, but also designing the buildings—and then gave a brief biography of her (and a plug for her book) before ending with the condemnation her movement had attracted from Douglas Reed in the Economic Council Letter. Abuse from the powers-that-be was, to Forteans, proof of goodness.

Thayer again mentioned Crosby and her works later in that same issue, when enumerating all the great things accomplished by Forteans. He said her symbol was one Forteans “could admire.” And when Greece disagreed, and Thayer got word she’d been thrown out, he kept not only Russell up to date (in a letter), but the rest of the readership, in the following issue, Doubt 42 (October 1953). Along with a sketchy rundown of the events, Thayer included two photographs of Crosby in Greece, re-rain the World Citizen’s symbol, included the longer plug for her autobiography, and gave three paragraphs to the “Proclamation for a People’s World Convention” that emerged from a three-day conference in Colorado Springs (and added the name of the group’s magazine and where to subscribe).

Issue 44 (April 1954) kept up the drumbeat. He noted that the Greek courts had ruled against Crosby. She was in the throes of editing the various documents into a coherent story that coulee be published. Meanwhile, she was a candidate to be a delegate at the next People’s World Convention. And Thayer included with the magazine that group's proclamation. (I have not seen it.) He concluded, “The set-back has not stopped Caresse. Fortean World Citizens will do well to give her their support through PWC.”

And, indeed, she had not given up hope. “I would like to make sone radio talks in America on my return in January,” she wrote in September 1953, “but perhaps what I have to say is too hot stuff for the radio to handle.” Showing that she understood Thayer’s Forteanism as opposition to authority, she noted acidly, “To conform is to succeed according to Mr. McCarthy.” Later in 1954, she was planning another trip to Greece for the following year. “I wonder just how they will treat me when I return . . . but perhaps by then the shepherd and the eagle will be the only ones left to receive me on the slopes of Mt. Parnassus.”

Tragedy struck in 1955. Thayer reported in Doubt 49 (August 1955): “Our own first citizen of the world, Caresse Crosby, has suffered personal illness and a tragic loss in the accidental death of her son, all since the Greek government reversed itself after welcoming her movement to Greek soil. Complete court proceedings and much international press comment is in our hands, but we understand that Caresse plans to present the entire story in book form as soon as she is able.” Personally, he had written her in January,

“Dear, dear Caresse:

“You have hardly left our thoughts a moment since we learned of your shopping loss. We are stunned, devastated, speechless before the monstrous unfairness and injustice of a fate so hard. Where, in all classic tragedy is a heroine to compare? O, dear, brave girl, our hearts ache for you.

“Tiffany and Kathleen.”

Crosby seems to have been relatively ill into 1956; she’d had pneumonia, and was still seeing doctors about her poor health into 1956. I do not know exactly what she said to Thayer—if there was a letter, it is not in her papers—but something along the lines of her doctor thinking she needed to curtail her activities, and her refusing the advice. Thayer congratulated her: “With this fist I will sock the Doc who calls you a bad risk. That’s equivalent to advising a deep sea diver not to get his feet wet. All the same, we are just as happy not to have you in the clutches of Science again. It will be a Fortean triumph for you to get well without their help, and you’re the girl who can do it.”

At the same time, Thayer had just published the first installment in his Mona Lisa series—a book that had been the works for a good decade. Crosby tried to order an autographed copy from him, but he demurred, preferring that the sale go through her regular bookseller. “I like to see bop fide dealers make their profit. It’s little enough.” She apparently complied. Otherwise, she seemed very busy and not connecting much with the Thayers. Tiffany was worried.

Meanwhile, another problem emerged: Garry Davis. Thayer had been disappointed in Davis almost as soon as he joined, comparing him unfavorably to Crosby in issue 41: “Garry lost interest in World Citizenship a long while ago, and the less said about him the better.” It seems that the problem was Davis was intent on forging his own institutions rather than joining forces with there one-worlders as Crosby had, creating competition where there shouldn’t have been. In late 1956, he ran into some of his periodic legal problems while in Europe, then returned to the U.S. He made the papers for his apparent hypocrisy: he complained about being on parole in the U.S. when he was a citizen here. “This is my country, I am a resident here,” he said.

Some time in early 1957, he gave an interview with Mike Wallace (yes, that Mike Wallace), which had the Thayer’s upset. Tiffany wrote, “Kathleen almost cried to witness your ideals and my sympathies so badly abused. I expected nothing less. Although it may be impossible—or impracticable—for you to disavow any connection with his brand of world citizenship, in my opinion it is an enormous fallacy to tolerate his incompetence and irresponsibility for the sake of the press he commands. He commands that press only as a clown. From now on the opposition will attempt to foster the Davis brand of world citizenship to bring ridicule upon the basic concept which you and I hold so dear.”

Mostly, though, with Thayer and Crosby were resigned to Davis’ activities, but no less hopeful. Thayer wrote, “This is not intended as advocacy of complaisance on your part or mine, but do accept my assurance that ‘your ideals and my sympathies’—as mentioned above—are inevitable of realization, whether we live to see it or not. What we are trying to tell them today will BE, eventually. Nothing can stop it, not even Garry Davis.” Meanwhile, Crosby told Thayer:

“L’affaire Davis has become quite a problem. We of the Commonwealth (and he was a member) have been planning and suggesting tot he UN a World Citizens Corps, ‘non-military’, as a service arm of the UN Police Force. Our proposal has been well received by delegates to the UN, also by governmental agencies. However, immediately on Garry’s unexpectedly quick return to the U.S. he with the help of Daniel Boone (Dr. Boone is one of our Council members) is calling for high school youth to form a World Citizen Unit and offer themselves through him as a World Citizens Corps, militarized, telling them this can be done instead of military service of the U.S. You can see that this can bring about confusion and some hazard in the Commonwelath’s relations with governments. . . . What to do?

“One heartening demonstration has been made by one of our Citizens, John Boardman, in Tallahassee, who in upholding desegregation on the campus there, where he attends the university, has made a statement and backs up his stand both in deed and word. . . .

“I found a really active interest in World Citizenship, in San Francisco where I spent last week. There still seems no possibility of appealing to ‘the masses’, but to the ‘élite’, yes.”

Doubt ran only one more piece on the world citizen movement, in issue 52 (May 1956). It was headed by the same symbol (Davis used a similar one) and documented Crosby’s latest activities in “making the world safe for rationality, even against present appealing odds.” She was now counsellor to the Commonwealth of World Citizens, based in Washington, D.C, which was set to adopt a constitution in September (personally, Thayer told her, “my anarchistic bent is away from constitutions as from any other straight-jacket”). He recommended that Forteans get involved snd send money as well as ideas.

But while Doubt stopped covering the movement, Thayer himself did not stop his support of Crosby; nor did his wife, Kathleen. In April 1957, he sent Crosby a list of London Forteans who might help her when she was there—W.P. Hibbert, Eric Frank Russell “the real black shepherd of British Forteans”), Francoise Delisle (“She is now very old, and in poor circumstances, but is still a fiery spirit and active mentally”), and Judith L. Gee “(“a Jewess who wears a hearing aid and hates Russell, who hates Jews”). He also recommended that she contact the pseudonymous “Diogenes,” who wrote for “Time and Tide.” (This was the English politician and trade unionist William John Brown.)

In 1958, Thayer continued to advise Crosby on how to get the word out about her movement, as she recovered form yet another illness and hospital visit. He suggested that she do a TV interview, particularly one with Mike Wallace. Thayer thought he was a “fairly sincere humanitarian” but distrusted the sponsors he had developed since taking his show national—they wanted spectacle. Go directly to Wallace, he said, and then, perhaps, Thayer could kick his own PR contacts into gear. He hoped to get to Greece to see her, but work continually beckoned, and he was guilty about not doing more on his “Mona Lisa” series and so never made the trip.

Tiffany ran out of time, dying in August 1959. Kathleen continued to correspond with Crosby, though, at least for a few years. They missed connections again and again, and Kathleen hoped to make it to Rome and surprise Crosby, but those plans, too, fell through. And then they drifted their different ways, in large part it seems because Kathleen became involved with her new husband and new life.

For a time, though, the Fortean Society and the World Citizens movement had been complementary forces—hoping to mold earth into a form that reflected their idea of rationality.

Relocated to Virginia, Crosby remained a patron of modernist literature, supporting, among others, Henry Miller. In the early 1940s, she opened a modern art gallery in Washington, D.C., and started a magazine, “Portfolio.” It ran six issues, publishing avant-garde writers, before folding. Crosby had written some poetry in her earlier years, but really didn’t consider herself an artist—she was not unlike James Laughlin in that regard, a dabbler in the arts who made her mark as a patron. But in 1953, she published her autobiography, “The Passionate Years.” In 1955, her son died in an automobile crash.

By this time, Crosby had become involved in politics. Living in Rome, but traveling frequently to the U.S., she was a dedicated peace activist. (Seeing two husbands psychically destroyed by war may have contributed.) Like Clara Studer and Garry Davis—fellow Forteans; Studer an acquaintance and fellow ex-pat in Italy—she also advocated for the dissolution of national boundaries and world citizenship. In the 1950s, she tried to establish a base of operations in Greece, but the movement fell apart.

Caresse Crosby died 24 January 1970, aged 78, in Rome, Italy.

***************

The first connections between Caresse Crosby and the Fortean Society are not as easy to trace as those between the Studers and the Society, but they seem to have grown out of the same network: Ezra Pound was a node. Somewhat surprisingly, for all that Crosby was fairly well known in the 1940s and 1950s—not a much as in the 1920s, neither was she as obscure as when she died—Crosby seems to have been genuinely involved with the Fortean Society: a friend of Tiffany Thayer, primarily, but also interested in the political dissent that he published in Doubt.

The earliest connection I can find between the Society and Crosby is the March of 1950, when Thayer wrote to her. (The letter is preserved in her papers at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.) It was a brief note, care of Crosby at the Black Sun Press—which would see its end that year—in Washington, D.C: “We must have met somewhere, but I don’t think it was in Paris. I was there in ’30 but met only dragomen (some nice ones). Do you sometimes get out to the hospital to see Ezra?” It’s a fairly cryptic message, made the more so by the lack of any preserved response. Nonetheless, Thayer’s introduction shows that he and Caresse ran in some of the same circles, and the center of the Venn Diagram was Ezra Pound. There would have been other connections, too—Henry Miller, for example.

Crosby seems to have responded positively to Thayer, and was mentioned in Doubt a year later—issue 31, March 1951. She was among a number of people who contributed a story about a girl in Kansas who had to undergo surgery—because a sunflower grew in her lungs. The girl was two; the sunflower half an inch long. The story was carried on the U.P. wires. It is, of course, possible that the story was sent in by someone else with the surname Crosby, but I have seen no reference to any other Crosby in Doubt, so do not think so. Apparently, Thayer’s (re)opening gambit got her to join as a member.

The connection seemed to be stronger than mere membership, though. Thayer had long nursed a hope to return to Europe, and his plans evolved to fit a meeting with her onto his itinerary. He mentioned to Eric Frank Russell in June 1951 that he would go to Rome and see her at her castle, which was called “Free World.” (By this point, Thayer had spent about half-a-decade researching and writing a novel on the Mona Lisa, and so had developed quite the fondness for Italy.) As it turned out, Thayer did not make the trip until 1952, and through some kind of mis-communication, he missed meeting with her.

Thayer did manage a meeting in March of 1953, though—Thayer told Russell he had dinner with her. The correspondence is not perfectly clear, but it seems as though she also engaged him to do some publicity for her—he was, after all, in public relations. From what I can gather, Thayer wrote an article about Crosby and her world citizenry movement for “The American Weekly.” He was also helping promote her book “The Passionate Years,” pushing it hard in issue 41 (July 1953). She told him, “I am thrilled that you will do something more on it too. I don’t expect I can outsell Mr. Kinsey but I would like to outstrip Bing [Crosby, who had published his memoir].”

For his part, Thayer was impressed by the autobiography. He wrote about it in Doubt 42 (October 1953): “We were so crowded for space last issue that we did not give MFS Crosby’s autobiography as much praise as it deserves. Besides the interest of the subject matter and the intimate view of the arts of the period, it is a writing feat which professionals will enjoy for technical reasons, The style is unique and engaging. You think you are looking at a nose-gay of rosebuds, surrounded by the tulle or rumpled lace panties, only to discover—suddenly—that there’s a rapier in the heart of it.”

He also tipped his hat to Crosby and her associates for all the obvious hard work that had gone into their efforts advocating for world citizenship. But he was not ready to sign on: “being an anarchist I don’t believe in any government at all, and so cannot subscribe to [Hugh J.] Schofield’s Constitution or sign up as a member.” Still, “eager to help spread the concept of World Citizenship and to help others find their way to participation.” He could not believe how disorganized Crosby was, despite the work she was putting into the movement. The article for “American Weekly” was falling apart because her assistants could not get material to him in a timely manner, and none of her associates seemed equipped to deal with the good publicity that would come from the article.

Thayer thought that “lime most idealists,” Crosby lacked “any sense of organization. . . . What is the sense of stirring up excitement in the American Weekly or anywhere else if nobody is prepared to sign up the applicants.” No one even had the address of Hugh J. Schonfield, the lawyer who was one of the central hubs in the push for creating new, peaceful sovereign nation of world citizens. “Lordy, lady. You can’t do business that way. . . . Somebody in the USA must be equipped with a supply of ‘literature’, a roster of the enrolled, application blanks, pins and buttons and what not all.” He was tempted to take on the job himself, but his convictions prevented it. Lest she worry that he was upset, Thayer added, “Don’t think I am ill tempered or crochet. It is just that I have enough business-man in me to appreciate that radicals, artists and idealists have to be efficient to get anywhere.”

It was that businessman in him that also encouraged her to roll with the current publicity for “The Passionate Years,” though she might not like it: “Dial’s ad was meant to see books, no matter how. I am afraid that—the public being what it is—the only way to get sensational volume is by being sensational. I quite understand your reaction, but one cannot be in good taste and ‘popular’ at the same time.” It was a creed Thayer had lived by himself, accepting the poor judgment of critics and attacks on him as déclassé in order to sell books.

Crosby appreciated Thayer’s help. After missing meeting each other again in 1954, she insisted that they needed to get together to talk. And then in 1957, after several more missed engagements—and a couple made—she wrote, “I miss your wisdom and counsel so very much, especially now when greater problems than ever have arisen and World Citizens in many countries look to me for decisions.” And she helped to spread word of the Fortean Society and Doubt among her circle. In 1953, she subscribed to the magazine for Charles Olson, the poet (who would use some Fortean themes in his work); Andre Magnus, a public relations executive in the French film industry; and Edward Durrell Stone, the architect. (Olson was at North Carolina’s Back Mountain College, and Thayer started getting that experimental school’s reviews again, which he liked better than earlier numbers.) She also handed out issues of Doubt to friends, acquaintances, and people with whom she was doing business.

In the end, Crosby was sanguine about the article for American Weekly falling through, since her efforts had a setback at just that moment. In 1942, she had purchased a house in Delphi, Greece; a decade later, she was trying to make that the center of her world citizenship activism. She went to visit in October 1952 and was arrested by Greek police as a threat to the economy and politics of the country. There were various machinations in court, and Crosby tried to establish her center in Cyprus, instead, but the Greek government had its way. The Cyprus center was to be housed in a geodesic dome designed by R. Buckminster Fuller, another Fortean.

Thayer kept up a steady commentary on her efforts. Issue 41 of Doubt (July 1953) had as its cover the symbol of the World Citizens movement emblazoned on an announcement that Crosby had given to Thayer—Pietro Lazzari’s sculptures were on sale to raise money for an “Artists’ Delphic Fund.” A three-column essay on the movement then led off the issue. The piece started, “Not every Fortean will recognize himself as the hub, spokes and motive power of the world, as pictured on our cover, but that is what the design is getting at, as I understand it.

“The individual is the all important unit. Each is his own universe, Living is the chiefest of the arts, and the aim of the organization which has nailed this new Jolly Roger to its masthead is to see that the opportunity is not lacking anywhere on Earth for individuals to realize their fullest creative potentials. as universe builders and movers.

“The design is the symbol of the World Citizens movement, which claims a registration of about 600,000, and more coming in all the time. It was given to me by MFS Caresse Crosby just before she took off for Delphi, Greece.”

Crosby had left for Delphi to dedicate a footprint—and the soil on which it was impressed—to the movement. But Thayer had not yet heard the results of her attempt. This spot was to be a sovereign plot for the world citizen movement, belonging to no country. She hoped that there would be similar footprints around the world, until borders were perforated, and nations porous. “The National pattern is outmoded,” Thayer quoted her as saying. “National leaders have failed us. It is for man the world citizen to mould a future nearer to the heart’s desire.” He then went on to note ways Forteans could help—money, of course, but also designing the buildings—and then gave a brief biography of her (and a plug for her book) before ending with the condemnation her movement had attracted from Douglas Reed in the Economic Council Letter. Abuse from the powers-that-be was, to Forteans, proof of goodness.

Thayer again mentioned Crosby and her works later in that same issue, when enumerating all the great things accomplished by Forteans. He said her symbol was one Forteans “could admire.” And when Greece disagreed, and Thayer got word she’d been thrown out, he kept not only Russell up to date (in a letter), but the rest of the readership, in the following issue, Doubt 42 (October 1953). Along with a sketchy rundown of the events, Thayer included two photographs of Crosby in Greece, re-rain the World Citizen’s symbol, included the longer plug for her autobiography, and gave three paragraphs to the “Proclamation for a People’s World Convention” that emerged from a three-day conference in Colorado Springs (and added the name of the group’s magazine and where to subscribe).

Issue 44 (April 1954) kept up the drumbeat. He noted that the Greek courts had ruled against Crosby. She was in the throes of editing the various documents into a coherent story that coulee be published. Meanwhile, she was a candidate to be a delegate at the next People’s World Convention. And Thayer included with the magazine that group's proclamation. (I have not seen it.) He concluded, “The set-back has not stopped Caresse. Fortean World Citizens will do well to give her their support through PWC.”

And, indeed, she had not given up hope. “I would like to make sone radio talks in America on my return in January,” she wrote in September 1953, “but perhaps what I have to say is too hot stuff for the radio to handle.” Showing that she understood Thayer’s Forteanism as opposition to authority, she noted acidly, “To conform is to succeed according to Mr. McCarthy.” Later in 1954, she was planning another trip to Greece for the following year. “I wonder just how they will treat me when I return . . . but perhaps by then the shepherd and the eagle will be the only ones left to receive me on the slopes of Mt. Parnassus.”

Tragedy struck in 1955. Thayer reported in Doubt 49 (August 1955): “Our own first citizen of the world, Caresse Crosby, has suffered personal illness and a tragic loss in the accidental death of her son, all since the Greek government reversed itself after welcoming her movement to Greek soil. Complete court proceedings and much international press comment is in our hands, but we understand that Caresse plans to present the entire story in book form as soon as she is able.” Personally, he had written her in January,

“Dear, dear Caresse:

“You have hardly left our thoughts a moment since we learned of your shopping loss. We are stunned, devastated, speechless before the monstrous unfairness and injustice of a fate so hard. Where, in all classic tragedy is a heroine to compare? O, dear, brave girl, our hearts ache for you.

“Tiffany and Kathleen.”

Crosby seems to have been relatively ill into 1956; she’d had pneumonia, and was still seeing doctors about her poor health into 1956. I do not know exactly what she said to Thayer—if there was a letter, it is not in her papers—but something along the lines of her doctor thinking she needed to curtail her activities, and her refusing the advice. Thayer congratulated her: “With this fist I will sock the Doc who calls you a bad risk. That’s equivalent to advising a deep sea diver not to get his feet wet. All the same, we are just as happy not to have you in the clutches of Science again. It will be a Fortean triumph for you to get well without their help, and you’re the girl who can do it.”

At the same time, Thayer had just published the first installment in his Mona Lisa series—a book that had been the works for a good decade. Crosby tried to order an autographed copy from him, but he demurred, preferring that the sale go through her regular bookseller. “I like to see bop fide dealers make their profit. It’s little enough.” She apparently complied. Otherwise, she seemed very busy and not connecting much with the Thayers. Tiffany was worried.

Meanwhile, another problem emerged: Garry Davis. Thayer had been disappointed in Davis almost as soon as he joined, comparing him unfavorably to Crosby in issue 41: “Garry lost interest in World Citizenship a long while ago, and the less said about him the better.” It seems that the problem was Davis was intent on forging his own institutions rather than joining forces with there one-worlders as Crosby had, creating competition where there shouldn’t have been. In late 1956, he ran into some of his periodic legal problems while in Europe, then returned to the U.S. He made the papers for his apparent hypocrisy: he complained about being on parole in the U.S. when he was a citizen here. “This is my country, I am a resident here,” he said.

Some time in early 1957, he gave an interview with Mike Wallace (yes, that Mike Wallace), which had the Thayer’s upset. Tiffany wrote, “Kathleen almost cried to witness your ideals and my sympathies so badly abused. I expected nothing less. Although it may be impossible—or impracticable—for you to disavow any connection with his brand of world citizenship, in my opinion it is an enormous fallacy to tolerate his incompetence and irresponsibility for the sake of the press he commands. He commands that press only as a clown. From now on the opposition will attempt to foster the Davis brand of world citizenship to bring ridicule upon the basic concept which you and I hold so dear.”

Mostly, though, with Thayer and Crosby were resigned to Davis’ activities, but no less hopeful. Thayer wrote, “This is not intended as advocacy of complaisance on your part or mine, but do accept my assurance that ‘your ideals and my sympathies’—as mentioned above—are inevitable of realization, whether we live to see it or not. What we are trying to tell them today will BE, eventually. Nothing can stop it, not even Garry Davis.” Meanwhile, Crosby told Thayer:

“L’affaire Davis has become quite a problem. We of the Commonwealth (and he was a member) have been planning and suggesting tot he UN a World Citizens Corps, ‘non-military’, as a service arm of the UN Police Force. Our proposal has been well received by delegates to the UN, also by governmental agencies. However, immediately on Garry’s unexpectedly quick return to the U.S. he with the help of Daniel Boone (Dr. Boone is one of our Council members) is calling for high school youth to form a World Citizen Unit and offer themselves through him as a World Citizens Corps, militarized, telling them this can be done instead of military service of the U.S. You can see that this can bring about confusion and some hazard in the Commonwelath’s relations with governments. . . . What to do?

“One heartening demonstration has been made by one of our Citizens, John Boardman, in Tallahassee, who in upholding desegregation on the campus there, where he attends the university, has made a statement and backs up his stand both in deed and word. . . .

“I found a really active interest in World Citizenship, in San Francisco where I spent last week. There still seems no possibility of appealing to ‘the masses’, but to the ‘élite’, yes.”

Doubt ran only one more piece on the world citizen movement, in issue 52 (May 1956). It was headed by the same symbol (Davis used a similar one) and documented Crosby’s latest activities in “making the world safe for rationality, even against present appealing odds.” She was now counsellor to the Commonwealth of World Citizens, based in Washington, D.C, which was set to adopt a constitution in September (personally, Thayer told her, “my anarchistic bent is away from constitutions as from any other straight-jacket”). He recommended that Forteans get involved snd send money as well as ideas.

But while Doubt stopped covering the movement, Thayer himself did not stop his support of Crosby; nor did his wife, Kathleen. In April 1957, he sent Crosby a list of London Forteans who might help her when she was there—W.P. Hibbert, Eric Frank Russell “the real black shepherd of British Forteans”), Francoise Delisle (“She is now very old, and in poor circumstances, but is still a fiery spirit and active mentally”), and Judith L. Gee “(“a Jewess who wears a hearing aid and hates Russell, who hates Jews”). He also recommended that she contact the pseudonymous “Diogenes,” who wrote for “Time and Tide.” (This was the English politician and trade unionist William John Brown.)

In 1958, Thayer continued to advise Crosby on how to get the word out about her movement, as she recovered form yet another illness and hospital visit. He suggested that she do a TV interview, particularly one with Mike Wallace. Thayer thought he was a “fairly sincere humanitarian” but distrusted the sponsors he had developed since taking his show national—they wanted spectacle. Go directly to Wallace, he said, and then, perhaps, Thayer could kick his own PR contacts into gear. He hoped to get to Greece to see her, but work continually beckoned, and he was guilty about not doing more on his “Mona Lisa” series and so never made the trip.

Tiffany ran out of time, dying in August 1959. Kathleen continued to correspond with Crosby, though, at least for a few years. They missed connections again and again, and Kathleen hoped to make it to Rome and surprise Crosby, but those plans, too, fell through. And then they drifted their different ways, in large part it seems because Kathleen became involved with her new husband and new life.

For a time, though, the Fortean Society and the World Citizens movement had been complementary forces—hoping to mold earth into a form that reflected their idea of rationality.