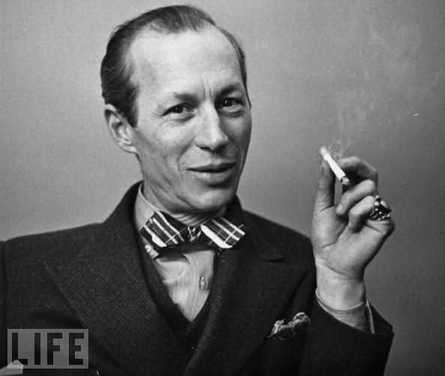

A champion of Fort—and a founder of the Society—but not really a Fortean.

Arthur Burton Rascoe was born 22 October 1891in Fulton, Kentucky, to Matthew Lafayette and Elizabeth (Burton) Rascoe. The family moved to Shawnee, Oklahoma, where Arthur and his brothers Henry and George spent their childhoods. According to family lore, the paterfamilias Matthew was saloon keeper, whose fortunes changed when Oklahoma went dry. He went into farming. The census has the family in Fulton in 1900—where Matthew was a hotel clerk—and Shawnee in 1910—where he was a farmer. Oklahoma went dry in September 1907—a few months before it became a state; it allowed for alcohol sales only in 1959.

Rascoe was inclined to literature; he attended the local schools, and worked at the “Shawnee Herald” when he was 14—so just around the time his family’s fortunes changed. In 1911, he moved to Chicago to attend the university there, and became the Chicago Tribune correspondent for the University of Chicago. He left the university after two years, and went to work for the Tribune full time as a reporter and assistant city editor. Rascoe married Hazel Luke on 5 July 1913. They had two children, Arthur Burton (born in 1914) and Helen Ruth (born in 1918).

Arthur Burton Rascoe was born 22 October 1891in Fulton, Kentucky, to Matthew Lafayette and Elizabeth (Burton) Rascoe. The family moved to Shawnee, Oklahoma, where Arthur and his brothers Henry and George spent their childhoods. According to family lore, the paterfamilias Matthew was saloon keeper, whose fortunes changed when Oklahoma went dry. He went into farming. The census has the family in Fulton in 1900—where Matthew was a hotel clerk—and Shawnee in 1910—where he was a farmer. Oklahoma went dry in September 1907—a few months before it became a state; it allowed for alcohol sales only in 1959.

Rascoe was inclined to literature; he attended the local schools, and worked at the “Shawnee Herald” when he was 14—so just around the time his family’s fortunes changed. In 1911, he moved to Chicago to attend the university there, and became the Chicago Tribune correspondent for the University of Chicago. He left the university after two years, and went to work for the Tribune full time as a reporter and assistant city editor. Rascoe married Hazel Luke on 5 July 1913. They had two children, Arthur Burton (born in 1914) and Helen Ruth (born in 1918).

This period was the so-called Chicago literary Renaissance, when modernist literature became important and there was a Bohemian culture that included the likes of Ben Hecht, the first Fortean. In print, Rascoe championed Sherwood Anderson and Theodore Dreiser and H. L. Mencken and James Branch Cabell. He celebrated the incorporation of Nietzsche into American letters, In addition to his newspaper work, Rascoe wrote for the Bookman, Dial, the New Republic, and Mencken’s “Smart Set,” among other publications. Indeed, Hecht remembered meeting Rascoe during these years, calling him “the skinny, stuttering savant from Oklahoma.”

For a short time, he was literary and drama editor at the Chicago Tribune, in 1920, before the newspaper—in his own words—“got fed up with the independence of my opinions and point of view.” Rascoe was well known for a punchy style and literary arguments. Rascoe's critical theory was personal, by his own reckoning. He said he liked what he liked, and proclaimed it greatly to get noticed, sometimes to the point of overpraising it. He picked fights in order to gain notice for authors he appreciated. There was, as well, aa journalistic ethos t his writing. He did spend time in the University of Chicago library, going through academic journals, looking for ideas to write about. But his approach was mainly based on a reporter’s instinct: “As a critic, he is a wonderful newspaper man,” one commenter said. “If he goes down in history at all, it will be as an encourager of new talents. He smells them out not by their artistic fragrance but by virtue of as a keen a nose for news as ever anyone was gifted with.”

Nonetheless, his biographer Donald Hensley argues that there were certain qualities of writing to which Rascoe was drawn. These were a Romantic belief that reality exists only in the imagination: he appreciated realism, but recognized that it was still a set of conventions, and the point was to stimulate the imagination. This criteria was in effect for historical and nonfictional writing, as well. He also believed that the primary duty of art was to transmit an emotional experience; political and social and intellectual points were to be secondary. Finally, he believed that criticism itself was a separate art for; that it was, as Anatole France said, the record of a soul in the presence of masterpieces. As Rascoe had it, this approach was European, and he had special affection for European literature, which he read in the original language frequently; he claimed to champion Proust four years before his work had been released in English.

Having left the Chicago Tribune, Rascoe and his family relocated to New York City, where he was briefly an associate editor at McCall’s before becoming literary editor at the New York Tribune. He started his series “A Bookman’s Day Book” there. In 1924, the Tribune merged with the Herald, and Rascoe was let go. He continued putting out his series as a freelance writer, in addition to penning the syndicated “Book of the Week.” His byline appeared frequently in other literary publications. In 1925, he published his first book, an appreciation of Theodore Dreiser, whom he had come to know first through correspondence, then in person.

Rascoe continued arguing for modernism and against Victorian literature—which he saw personified in the literary criticism of Stuart Pratt Sherman. Indeed, much of his book on Dreiser was given to carping about Sherman. For him, Dreiser wrote about the modern era with a clear-eyed perspective. The book is more than a little hagiographic, absolving Dreiser of greed and narcissism, but instead seeing the world objectively because of his down-home Indiana roots (one wonders if there’s not projection here): “He is alone in having achieved a perspective upon the great human drama involved in the war of finance, and thus in being able to treat it with the same detachment that epic poets have had toward heroic events of the remote past.”

Not that Rascoe was in favor of all developments in literature. He had promoted the poetry of T.S. Eliot, but objected to the New Humanism, to which Eliot was attached. (So was Sherman). Rascoe thought it snobbery disguised as literature. He didn’t like the Algonquin Group, either—of which Fortean Alexander Woollcott was a member—because of its pretensions. He sniffed at some of Dreiser and Hecht’s later works for being too political and not literary enough. He took exception to Mencken at times, as well, for being anti-intellectual.

Through the late 1920s and into the 1930s, Rascoe continued to move among jobs, and sometimes hold multiple positions. He was editor of “The Bookman” in 1927 and 1928 and was on the editorial board of the Literary Guild of America from 1928 to 1937. He edited “Plain Talk” from 1929 to 1930. Meanwhile, his syndicated work continued. “A Bookman’s Daybook,” published in 1929, collected some of this work. He wrote “Titans of Literature” and “Prometheans” in 1932 and 1933, respectively, about influential authors. His “Joys of Reading” came out in 1937; so did a memoir, “Before I Forget.”

It is hard to get a hold of Rascoe’s financial situation at this time. He told Dreiser he was occasionally worried over money—but not out of the ordinary, he didn’t think; but the family seemed to maintain two households, with Burton lodging at a place on Fourth Avenue, while the Hazel and the kids were out in Larchmont. Meanwhile, his family’s situation had improved once more. Again according to family stories, oil had been found on their land, and they moved to California in style. The 1930 census had Matthew, Elizabeth, and George living in Burlingame, California, just south of San Francisco. Matthew owned an $8,000 home and employed a servant. Divorced, George was an artist, the only one in the family home who had a job listed.

The 1930s was a hinge decade for Rascoe: going into them, he was still well-respected, but coming out he was no longer. He went to work as an editor for Esquire in 1932, and stayed in place until 1938; he was also an editorial advisor at Doubleday from 1934 to 1937 and literary critic at Newsweek in 1938 and 1939. By the end of the decade, he had moved to the “American Mercury,” Mencken’s old rag—he and Mencken were on the outs, though. In 1935, Mary McCarthy—at 22, the leader of a new generation of literary critics—attacked Rascoe in the pages of the “New Republic,” calling him an anti-intellectual who used his position to plug the books of his favorite authors; in part, his championing of Fort was adduced as evidence for the claim. It wasn’t exactly a fair critique—Rascoe was not anti-intellectual—but his failure to explain the ideas behind his criticism left him open to such attacks by the more ideologically informed McCarthy. His 1937 memoir was embroiled in legal problems when he was sued for libel.

Amid this all was tragedy: on 19 September 1936, Rascoe Junior, aged 22, turned on the stove gas and killed himself.

Rascoe fell into obscurity in the 1940s. He uncharitably reviewed Steinbecks “Grapes of Wrath”—according to a niece, this was because one of his brothers, now rich in California, said Steinbeck had gotten the history wrong. In 1942, he and Hazel were living in New York, but he was working for the Chicago Sun. The second of his memoirs, “We Were Interrupted,” did not appear until 1947, and in the 1950s he was a television reviewer, writing the syndicated column “TV First-Nighter.” He had become increasingly cantankerous before developing into a hard-bitten right winger, defending Joe McCarthy. His daughter, Ruth, would pass away in 1968, and Hazel in 1971.

(Arthur) Burton Rascoe died of heart failure 19 March 1957. He was 65.

***********************

Exactly when Rascoe first came upon Fort is not known. The science fiction fan and historian Sam Moskowitz thought that Dreiser had more-or-less blackmailed Rascoe into reading Fort (the way he more-or-less blackmailed his publisher into putting it out): “Barton [sic] Rascoe, highly respected critic of the era, found that the price of getting the information he needed for a biography of Theodore Dreiser was forced reading of Fort. He converted and became a rabid acolyte.” Moskowitz’s conclusions are not always tone trusted, and especially when it comes to Fort, as his intention was to prove Fort was neither innovative nor very influential. It still may be the case that Moskowitz was right, but he gives no sense of where he got the claim, and it doesn’t fit very well with the available evidence.

Correspondence between Dreiser and Rascoe began, as far as I can tell, in 1919, when Rascoe wrote a fan letter. It continued on sporadically into the 1920s, and though both of the men moved through Chicago and New York literary scenes, they did not meet for a number of years. On 11 December 1922, Rascoe invited Dreiser to lunch with him, adding “I should very much like to meet you in person.” There is then no correspondence between them, at least that still exists, until 20 July 1925, when Rascoe wrote that he was glad Dreiser liked the book—meaning Rascoe’s book on Dreise,r which had come out earlier in the year. Maybe the trade-off had occurred in person, but then the question becomes, Why? The book makes no mention of Fort and, more to the point, no special access would have been needed to write it. A large percentage of the book is criticism of Sherman, and the discussion of Dreiser comprises basic biographical facts and digests of his books.

Otherwise, Rascoe does not seem to have much, if anything, to do with Fort until the founding of the Fortean Society. Perhaps he wrote a review of one or more of Fort’s books, but I have been unable to find it, if so. This lack of response to Fort by Rascoe does, it must be admitted, give some credence to Moskowitz’s claims, though it is negative evidence.

The next connection between Rascoe and Fort came with the machinations around the founding Fortean Society. In an undated piece of a letter from Thayer in Rascoe’s papers (at the University of Pennsylvania)—internal evidence suggests it was written after May 1930, and probably closer to October—Thayer wrote Rascoe asking, “Perhaps you share my enthusiasm for Charles Fort’s books. Do you? I am trying to start a Fortean Society—to pull the stars down upon the astronomer’s heads. I am talking to Theodore Dreiser about it in the morning. He is an old friend of Fort’s. Will you join? Tarkington is in it.”

Rascoe must have agreed. Aaron Sussman sent out a publicity letter on 21 January, five days before the first meeting, naming Rascoe among the founders. He was one of the few founders to actually make the meeting when it was held on a snowy night. Also there were Thayer and Dreiser and J. David Stern; Ben Hecht stopped by briefly.

And that was pretty much it for the Fortean Society in its first iteration. There was another announced meeting, but it was never held. The Society did its work, though: it was a publicity stunt, in the manner of literary teas which were frequent at the time as a kind of book launch party. (Tea was frequent substitute for alcohol during Prohibition—tea rooms replacing saloons.) “Lo!” was widely reviewed, and notice of it usually mentioned the Society and the famous members. Rascoe was among those who reviewed the book. His appeared on 15 February 1931 in the New York Herald Tribune:

“My expression is (to use the phrasal reservation of Charles Fort) that this book may or may not be one of the great books of the world, and that, since at the moment I am convinced that it is, it is high time (to use the Fortean formula of skepticism) for me to begin to doubt it. For, says Charles Fort, ‘I cannot accept the products of minds as subject matter for beliefs.’ But I accept ‘with reservations that give me freedom to ridicule the statement at any other time,’ that Charles Fort has engaged in investigations which make Einstein’s seem piddling and that Lo! is the ‘De Revolutionibus’ and the ‘Principia’ of a new era of discovery where in there will be an entirely new arrangement of our patterns of thinking. Though where did I get the idea that the ‘De Revolutionibus’ and the ‘Principia’ were important, or comparatively important, or of an importance equal to this book or that it might annoy somebody for me to mention the ‘Principia’ and Lo! in the same breath? And where did I get the idea that it would be salutary to have a new era of discovery or a new arrangement of our patterns of thinking?

“You will excuse me, but I cannot keep up the pretense of pursuing the Fortean process of really rational thinking or the attitude of mind which makes Charles Fort so singularly provocative a challenger of our sluggish, almost amoeba-like method of arriving at somatic death through an interval of accepting buncombe, from the cradle, as wisdom and scientific knowledge. I must frankly revert to type and to the species journalist. A Fortean of Forteans, willing to make the requisite gesture of shaking my finger at Charles Fort at any time I feel like doing so, and willing also to distrust whatever he says that seems too reasonable and full of common sense, because all the fallacies in the world are founded on reasonableness and common sense, I must yet, until I break up old habits of acceptances by habits of doubt, remain a journalist awed, impressed, fascinated, amused by what I consider one of the most amazing (a very good and handy journalistic word, ‘amazing’) books I have ever read.

“If I did not think that Charles Fort might suddenly go in seriously for teleportation, and upon reading this endeavor by process of thought to transfer me teleportatively to frigid Mars, the House of Representatives or a peak in Darlen, I should describe Charles Fort’s thinking as fifth-dimensional. But he would shake his head sadly at that.

You can read Lo! in almost any way you like or in any mood your temperament dictates and whatever way you read it, it is my expression that it is a great book. You make take it as pure fantasy and you will find it gorgeous stuff, full of poetic imagery, eloquent in the grand manner, beautiful to read. You may take it as an intellectual hoax and still you must admit it is a marvelously contrived one, satirical, subtle, full of laughs at the expense of the big-wigs of science. You may take it as a sort of pseudo-divine revelation with Charles Fort as a mere ‘agent’ of a higher force seeking to impart knowledge to us, and you will have to admit that Charles Fort opens up new, magic casements upon resplendent vistas.

“Charles Fort gives us a great new list of thinkables while at the same time showing us the absurdity of things we have been thinking or rather accepting without thinking. Not many years ago it was thinkable that I might talk to someone in Europe without moving from my chair in Larchmont, but there were certainly not many who would have agreed then that such a thing was thinkable. Charles Fort suggests that it is thinkable that when and if we know more about what he calls teleportation, a merchant in London might transfer almost instantly a carload of oranges from California to his warehouse in Limehouse simply by taking thought, ‘wishing’ the event. He entertains the notion that people have been transferred from one region to another; that the celebrated Casper Hauser, whose mysterious history the Encyclopedia Britannica admits science has been unable to explain, may have been a visitor from another planet, that the mystery of Dorothy Arnold might be explained by teleportation, that the miracle of the stigmata is a fact and not a hoax, pious fraud of hallucination, that frogs and snakes and snails and crabs and periwinkles have rained out of clear skies, that the Children of Israel not only were nourished by ‘manna’ that fell from the heavens but that in our own time ‘manna’ or an edible plant of unknown origin capable of being ground into excellent flour has fallen upon the same arid plains in Asia Minor.

“Charles Fort, by gathering and investigating curious data of earthly phenomena which science excludes or ‘explains’ rationalistically, opens up new worlds of speculation. He says that he does not ‘believe’ a thing in his book, he merely offers the data; but then he does not believe the astronomers and physicists and geologists and paleonthologists [sic], who also, by the way, do not believe one another. Dr. R. A. Milliken, who believes in Cosmic Rays and a Creator and that new energy is always being created, finds himself at odds with Jeans and Eddington--of whom one believes in a Creator and the other doesn’t, neither believes in Cosmic Rays, and both agree that the universe is running down like a clock.

“But it is not so much the strange data that Charles Fort offers of unexplained phenomena or the world of mystery he leads us into—the suggestion of teleportation and of the nearness of other planets to our own, of visitations from other planets and the dealing of death and plague by process of thought--that stimulates and delights me most in his books. It is his inveterately inquiring mind, his truly scientific skepticism, his showing up of the complete absurdity of common processes of deduction and of the dogmas we have all more or less accepted. He shows us, for example, that there is no such thing as a law of cause and effect, of supply and demand, and so on. He shakes up all of our complacencies; he gives a rude jolt to our articles of faith. He spares no one, not even himself. If you are a materialist or a mechanist, he gives aid and comfort to the enemy, the religionists and the mystics. But if you are a religionist or a mystic, he gives aid and comfort to the enemy also. I can well imagine H. L. Mencken and Bishop Manning reacting in the same degree, if not in kind, of fury at some of the ‘suggestions’ of Charles Fort. But, on the other hand, whoever heard of a stranger collection of bed fellows united under the same banner than Booth Tarkington and Ben Hecht, Harry Leon Wilson and Tiffany Thayer, John Cowper Powys and Louis Sherwin, Gorham Munson and myself, all of whom see something portentous and exciting in the curious delvings and speculations of a quiet, enigmatic, humorous-minded man who lived almost like a hermit in the Bronx?”

As far as I know, Rascoe had nothing further to do with Fort or the Fortean Society—though Thayer would pursue him, and he would be asked his opinion by others. I have not seen a review by him of Fort’s last book, 1932’s “Wild Talents.” Thayer approached him in early 1935, writing from Hollywood, telling him that he was rekindling the Fortean Society and hoped to put out a publicity book featuring pictures of the founders and their writings on Fort. “Your enthusiasm for Fort was not made known to me in time to quote you when we were active before,” he continued, “but I shall need something now. Won’t you write me a letter about the effect of Fort’s work on you?” he also asked for a picture that Rascoe favored, or he would get one from his publisher. I do not know if Rascoe bothered to write back, but if he idd it does not seem to have been particularly encouraging. Thayer never came out with the booklet.

As Thayer’s work reviving the the Fortean Society continued, he came into conflict with Dreiser over the ownership of Fort’s notes; Dreiser’s lawyer looked into the matter, asking various Founders what they knew of the proceedings. Rascoe was sour on the whole matter. Writing in July 1937 from his mother’s home in Burlingame, California, he called Thayer a “stubborn brat”: “As far as I was ever able to figure out the Fortean Society was a phoney organization, without dues, officers, members, meeting place or charter and was merely a scheme devised by the fertile publicity brain of Tiffany Thayer for the promotion of the sale of Charles Fort’s books and publicizing his name. It was my impression also that this was a disinterested labor of love with Thayer, for which he received no fee either from Fort or Fort’s publishers and that Thayer bore all the expense (not much, I should judge) . . . Thayer made up his list of ‘founders’ simply by learning the names of some of the well-known writers and [other] personages who enjoyed Fort’s work and were quite willing that their name should be used in any legitimate way to promote the sale of Fort’s books.”

The meeting was the only time he met Fort, he said. Thayer had talked at the time time to hire a secretary to transcribe and arrange Fort’s notes but those were nothing more than “clippings of silly whoppers from provincial newspapers all over the world . . . and that without Fort’s genius, as a writer, in the selective use of this data, it is just so much trash.” Which was his general opinion of the Fortean Society: “The question in your mind seems, unfathomably to me, to be whether the Fortean Society is defunct or still functioning. In the manner you mean, it never did function; for there never was any Fortean Society except as a figment of Thayer’s fancy.”

Heedless of the controversy he was causing, Thayer went forward, and dragged Rascoe’s name with him. He was one of the official Founders, and received the magazine for years and years; I do not know that Rascoe read them, though he did save them, and they ended up with his papers.

Thayer started bothering Rascoe about the Society again in 1940, just before the omnibus edition of Fort’s books came out. In January, he sent Rascoe his life membership card in the Society, and pleaded with him to write a thousand words on Fort for the next issue. If Rascoe couldn’t write something new, Thayer offered to dig up something old—he thought Rascoe might have written something for the magazine “Arts & Decorations.” He also asked Rascoe to lunch.

Again, nothing seems to have come from the overture, for in November Thayer wrote again, asking for the write-up on Fort and announcing the omnibus edition would be out the following year. He needed Rascoe’s piece “now.” To sugar the pot, he offered a compliment of a piece Rascoe had recently written on publishers. Still nothing. In April 1941, a few weeks after the omnibus edition came out, Thayer begged, “I know you’re busy, my lad, but you gotta give the Fort omnibus a send-off somewhere. . . Please get into print on the subject in as many spots as possible. I had Holt send your copy direct.” For reasons hard to understand, Thayer was certain Rascoe would come through and, on the same date, wrote to Tarkington saying Rascoe was in for promoting The Books. But as far as I know, he never wrote anything about Fort, nor did he respond to Thayer.

Proof of sorts of Rascoe’s ignoring everything came later in 1941. The Fortean magazine—not yet called Doubt—dated October 1941 featured Rascoe’s thoughts on Fort; this was part of Thayer’s series on the Founders, which included their writings on Fort—what remains of this plan to make the publicity pamphlet, it would seem. It had nothing from “Arts & Decorations” and nothing new. Rather, it was a reprint of Rascoe’s review of “Lo!” with “The Books of Charles Fort” inserted where “Lo!” had once been, and the excision of two sentences that implied Fort was still alive. It also mis-spelled one of the words from the original review. Rascoe was clearly not interested in Fort anymore, and seemingly never much interested in the Fortean Society.

Still, Thayer kept up the pretense. In 1951, when Thayer was considering making Fortean opposition to Civilian Defense, by running an ad for the Society that announced it as so, he sent letters canvassing the opinion of all the Founders. In the end, the Founders chose not to proceed with the plans. But rancor was likely not one of those to even voice an opinion. He did get a letter, and it is still preserved in the archives. But it into be doubted that he bothered saying anything.

He had long ago given up on Fort and the Society founded in his name.

For a short time, he was literary and drama editor at the Chicago Tribune, in 1920, before the newspaper—in his own words—“got fed up with the independence of my opinions and point of view.” Rascoe was well known for a punchy style and literary arguments. Rascoe's critical theory was personal, by his own reckoning. He said he liked what he liked, and proclaimed it greatly to get noticed, sometimes to the point of overpraising it. He picked fights in order to gain notice for authors he appreciated. There was, as well, aa journalistic ethos t his writing. He did spend time in the University of Chicago library, going through academic journals, looking for ideas to write about. But his approach was mainly based on a reporter’s instinct: “As a critic, he is a wonderful newspaper man,” one commenter said. “If he goes down in history at all, it will be as an encourager of new talents. He smells them out not by their artistic fragrance but by virtue of as a keen a nose for news as ever anyone was gifted with.”

Nonetheless, his biographer Donald Hensley argues that there were certain qualities of writing to which Rascoe was drawn. These were a Romantic belief that reality exists only in the imagination: he appreciated realism, but recognized that it was still a set of conventions, and the point was to stimulate the imagination. This criteria was in effect for historical and nonfictional writing, as well. He also believed that the primary duty of art was to transmit an emotional experience; political and social and intellectual points were to be secondary. Finally, he believed that criticism itself was a separate art for; that it was, as Anatole France said, the record of a soul in the presence of masterpieces. As Rascoe had it, this approach was European, and he had special affection for European literature, which he read in the original language frequently; he claimed to champion Proust four years before his work had been released in English.

Having left the Chicago Tribune, Rascoe and his family relocated to New York City, where he was briefly an associate editor at McCall’s before becoming literary editor at the New York Tribune. He started his series “A Bookman’s Day Book” there. In 1924, the Tribune merged with the Herald, and Rascoe was let go. He continued putting out his series as a freelance writer, in addition to penning the syndicated “Book of the Week.” His byline appeared frequently in other literary publications. In 1925, he published his first book, an appreciation of Theodore Dreiser, whom he had come to know first through correspondence, then in person.

Rascoe continued arguing for modernism and against Victorian literature—which he saw personified in the literary criticism of Stuart Pratt Sherman. Indeed, much of his book on Dreiser was given to carping about Sherman. For him, Dreiser wrote about the modern era with a clear-eyed perspective. The book is more than a little hagiographic, absolving Dreiser of greed and narcissism, but instead seeing the world objectively because of his down-home Indiana roots (one wonders if there’s not projection here): “He is alone in having achieved a perspective upon the great human drama involved in the war of finance, and thus in being able to treat it with the same detachment that epic poets have had toward heroic events of the remote past.”

Not that Rascoe was in favor of all developments in literature. He had promoted the poetry of T.S. Eliot, but objected to the New Humanism, to which Eliot was attached. (So was Sherman). Rascoe thought it snobbery disguised as literature. He didn’t like the Algonquin Group, either—of which Fortean Alexander Woollcott was a member—because of its pretensions. He sniffed at some of Dreiser and Hecht’s later works for being too political and not literary enough. He took exception to Mencken at times, as well, for being anti-intellectual.

Through the late 1920s and into the 1930s, Rascoe continued to move among jobs, and sometimes hold multiple positions. He was editor of “The Bookman” in 1927 and 1928 and was on the editorial board of the Literary Guild of America from 1928 to 1937. He edited “Plain Talk” from 1929 to 1930. Meanwhile, his syndicated work continued. “A Bookman’s Daybook,” published in 1929, collected some of this work. He wrote “Titans of Literature” and “Prometheans” in 1932 and 1933, respectively, about influential authors. His “Joys of Reading” came out in 1937; so did a memoir, “Before I Forget.”

It is hard to get a hold of Rascoe’s financial situation at this time. He told Dreiser he was occasionally worried over money—but not out of the ordinary, he didn’t think; but the family seemed to maintain two households, with Burton lodging at a place on Fourth Avenue, while the Hazel and the kids were out in Larchmont. Meanwhile, his family’s situation had improved once more. Again according to family stories, oil had been found on their land, and they moved to California in style. The 1930 census had Matthew, Elizabeth, and George living in Burlingame, California, just south of San Francisco. Matthew owned an $8,000 home and employed a servant. Divorced, George was an artist, the only one in the family home who had a job listed.

The 1930s was a hinge decade for Rascoe: going into them, he was still well-respected, but coming out he was no longer. He went to work as an editor for Esquire in 1932, and stayed in place until 1938; he was also an editorial advisor at Doubleday from 1934 to 1937 and literary critic at Newsweek in 1938 and 1939. By the end of the decade, he had moved to the “American Mercury,” Mencken’s old rag—he and Mencken were on the outs, though. In 1935, Mary McCarthy—at 22, the leader of a new generation of literary critics—attacked Rascoe in the pages of the “New Republic,” calling him an anti-intellectual who used his position to plug the books of his favorite authors; in part, his championing of Fort was adduced as evidence for the claim. It wasn’t exactly a fair critique—Rascoe was not anti-intellectual—but his failure to explain the ideas behind his criticism left him open to such attacks by the more ideologically informed McCarthy. His 1937 memoir was embroiled in legal problems when he was sued for libel.

Amid this all was tragedy: on 19 September 1936, Rascoe Junior, aged 22, turned on the stove gas and killed himself.

Rascoe fell into obscurity in the 1940s. He uncharitably reviewed Steinbecks “Grapes of Wrath”—according to a niece, this was because one of his brothers, now rich in California, said Steinbeck had gotten the history wrong. In 1942, he and Hazel were living in New York, but he was working for the Chicago Sun. The second of his memoirs, “We Were Interrupted,” did not appear until 1947, and in the 1950s he was a television reviewer, writing the syndicated column “TV First-Nighter.” He had become increasingly cantankerous before developing into a hard-bitten right winger, defending Joe McCarthy. His daughter, Ruth, would pass away in 1968, and Hazel in 1971.

(Arthur) Burton Rascoe died of heart failure 19 March 1957. He was 65.

***********************

Exactly when Rascoe first came upon Fort is not known. The science fiction fan and historian Sam Moskowitz thought that Dreiser had more-or-less blackmailed Rascoe into reading Fort (the way he more-or-less blackmailed his publisher into putting it out): “Barton [sic] Rascoe, highly respected critic of the era, found that the price of getting the information he needed for a biography of Theodore Dreiser was forced reading of Fort. He converted and became a rabid acolyte.” Moskowitz’s conclusions are not always tone trusted, and especially when it comes to Fort, as his intention was to prove Fort was neither innovative nor very influential. It still may be the case that Moskowitz was right, but he gives no sense of where he got the claim, and it doesn’t fit very well with the available evidence.

Correspondence between Dreiser and Rascoe began, as far as I can tell, in 1919, when Rascoe wrote a fan letter. It continued on sporadically into the 1920s, and though both of the men moved through Chicago and New York literary scenes, they did not meet for a number of years. On 11 December 1922, Rascoe invited Dreiser to lunch with him, adding “I should very much like to meet you in person.” There is then no correspondence between them, at least that still exists, until 20 July 1925, when Rascoe wrote that he was glad Dreiser liked the book—meaning Rascoe’s book on Dreise,r which had come out earlier in the year. Maybe the trade-off had occurred in person, but then the question becomes, Why? The book makes no mention of Fort and, more to the point, no special access would have been needed to write it. A large percentage of the book is criticism of Sherman, and the discussion of Dreiser comprises basic biographical facts and digests of his books.

Otherwise, Rascoe does not seem to have much, if anything, to do with Fort until the founding of the Fortean Society. Perhaps he wrote a review of one or more of Fort’s books, but I have been unable to find it, if so. This lack of response to Fort by Rascoe does, it must be admitted, give some credence to Moskowitz’s claims, though it is negative evidence.

The next connection between Rascoe and Fort came with the machinations around the founding Fortean Society. In an undated piece of a letter from Thayer in Rascoe’s papers (at the University of Pennsylvania)—internal evidence suggests it was written after May 1930, and probably closer to October—Thayer wrote Rascoe asking, “Perhaps you share my enthusiasm for Charles Fort’s books. Do you? I am trying to start a Fortean Society—to pull the stars down upon the astronomer’s heads. I am talking to Theodore Dreiser about it in the morning. He is an old friend of Fort’s. Will you join? Tarkington is in it.”

Rascoe must have agreed. Aaron Sussman sent out a publicity letter on 21 January, five days before the first meeting, naming Rascoe among the founders. He was one of the few founders to actually make the meeting when it was held on a snowy night. Also there were Thayer and Dreiser and J. David Stern; Ben Hecht stopped by briefly.

And that was pretty much it for the Fortean Society in its first iteration. There was another announced meeting, but it was never held. The Society did its work, though: it was a publicity stunt, in the manner of literary teas which were frequent at the time as a kind of book launch party. (Tea was frequent substitute for alcohol during Prohibition—tea rooms replacing saloons.) “Lo!” was widely reviewed, and notice of it usually mentioned the Society and the famous members. Rascoe was among those who reviewed the book. His appeared on 15 February 1931 in the New York Herald Tribune:

“My expression is (to use the phrasal reservation of Charles Fort) that this book may or may not be one of the great books of the world, and that, since at the moment I am convinced that it is, it is high time (to use the Fortean formula of skepticism) for me to begin to doubt it. For, says Charles Fort, ‘I cannot accept the products of minds as subject matter for beliefs.’ But I accept ‘with reservations that give me freedom to ridicule the statement at any other time,’ that Charles Fort has engaged in investigations which make Einstein’s seem piddling and that Lo! is the ‘De Revolutionibus’ and the ‘Principia’ of a new era of discovery where in there will be an entirely new arrangement of our patterns of thinking. Though where did I get the idea that the ‘De Revolutionibus’ and the ‘Principia’ were important, or comparatively important, or of an importance equal to this book or that it might annoy somebody for me to mention the ‘Principia’ and Lo! in the same breath? And where did I get the idea that it would be salutary to have a new era of discovery or a new arrangement of our patterns of thinking?

“You will excuse me, but I cannot keep up the pretense of pursuing the Fortean process of really rational thinking or the attitude of mind which makes Charles Fort so singularly provocative a challenger of our sluggish, almost amoeba-like method of arriving at somatic death through an interval of accepting buncombe, from the cradle, as wisdom and scientific knowledge. I must frankly revert to type and to the species journalist. A Fortean of Forteans, willing to make the requisite gesture of shaking my finger at Charles Fort at any time I feel like doing so, and willing also to distrust whatever he says that seems too reasonable and full of common sense, because all the fallacies in the world are founded on reasonableness and common sense, I must yet, until I break up old habits of acceptances by habits of doubt, remain a journalist awed, impressed, fascinated, amused by what I consider one of the most amazing (a very good and handy journalistic word, ‘amazing’) books I have ever read.

“If I did not think that Charles Fort might suddenly go in seriously for teleportation, and upon reading this endeavor by process of thought to transfer me teleportatively to frigid Mars, the House of Representatives or a peak in Darlen, I should describe Charles Fort’s thinking as fifth-dimensional. But he would shake his head sadly at that.

You can read Lo! in almost any way you like or in any mood your temperament dictates and whatever way you read it, it is my expression that it is a great book. You make take it as pure fantasy and you will find it gorgeous stuff, full of poetic imagery, eloquent in the grand manner, beautiful to read. You may take it as an intellectual hoax and still you must admit it is a marvelously contrived one, satirical, subtle, full of laughs at the expense of the big-wigs of science. You may take it as a sort of pseudo-divine revelation with Charles Fort as a mere ‘agent’ of a higher force seeking to impart knowledge to us, and you will have to admit that Charles Fort opens up new, magic casements upon resplendent vistas.

“Charles Fort gives us a great new list of thinkables while at the same time showing us the absurdity of things we have been thinking or rather accepting without thinking. Not many years ago it was thinkable that I might talk to someone in Europe without moving from my chair in Larchmont, but there were certainly not many who would have agreed then that such a thing was thinkable. Charles Fort suggests that it is thinkable that when and if we know more about what he calls teleportation, a merchant in London might transfer almost instantly a carload of oranges from California to his warehouse in Limehouse simply by taking thought, ‘wishing’ the event. He entertains the notion that people have been transferred from one region to another; that the celebrated Casper Hauser, whose mysterious history the Encyclopedia Britannica admits science has been unable to explain, may have been a visitor from another planet, that the mystery of Dorothy Arnold might be explained by teleportation, that the miracle of the stigmata is a fact and not a hoax, pious fraud of hallucination, that frogs and snakes and snails and crabs and periwinkles have rained out of clear skies, that the Children of Israel not only were nourished by ‘manna’ that fell from the heavens but that in our own time ‘manna’ or an edible plant of unknown origin capable of being ground into excellent flour has fallen upon the same arid plains in Asia Minor.

“Charles Fort, by gathering and investigating curious data of earthly phenomena which science excludes or ‘explains’ rationalistically, opens up new worlds of speculation. He says that he does not ‘believe’ a thing in his book, he merely offers the data; but then he does not believe the astronomers and physicists and geologists and paleonthologists [sic], who also, by the way, do not believe one another. Dr. R. A. Milliken, who believes in Cosmic Rays and a Creator and that new energy is always being created, finds himself at odds with Jeans and Eddington--of whom one believes in a Creator and the other doesn’t, neither believes in Cosmic Rays, and both agree that the universe is running down like a clock.

“But it is not so much the strange data that Charles Fort offers of unexplained phenomena or the world of mystery he leads us into—the suggestion of teleportation and of the nearness of other planets to our own, of visitations from other planets and the dealing of death and plague by process of thought--that stimulates and delights me most in his books. It is his inveterately inquiring mind, his truly scientific skepticism, his showing up of the complete absurdity of common processes of deduction and of the dogmas we have all more or less accepted. He shows us, for example, that there is no such thing as a law of cause and effect, of supply and demand, and so on. He shakes up all of our complacencies; he gives a rude jolt to our articles of faith. He spares no one, not even himself. If you are a materialist or a mechanist, he gives aid and comfort to the enemy, the religionists and the mystics. But if you are a religionist or a mystic, he gives aid and comfort to the enemy also. I can well imagine H. L. Mencken and Bishop Manning reacting in the same degree, if not in kind, of fury at some of the ‘suggestions’ of Charles Fort. But, on the other hand, whoever heard of a stranger collection of bed fellows united under the same banner than Booth Tarkington and Ben Hecht, Harry Leon Wilson and Tiffany Thayer, John Cowper Powys and Louis Sherwin, Gorham Munson and myself, all of whom see something portentous and exciting in the curious delvings and speculations of a quiet, enigmatic, humorous-minded man who lived almost like a hermit in the Bronx?”

As far as I know, Rascoe had nothing further to do with Fort or the Fortean Society—though Thayer would pursue him, and he would be asked his opinion by others. I have not seen a review by him of Fort’s last book, 1932’s “Wild Talents.” Thayer approached him in early 1935, writing from Hollywood, telling him that he was rekindling the Fortean Society and hoped to put out a publicity book featuring pictures of the founders and their writings on Fort. “Your enthusiasm for Fort was not made known to me in time to quote you when we were active before,” he continued, “but I shall need something now. Won’t you write me a letter about the effect of Fort’s work on you?” he also asked for a picture that Rascoe favored, or he would get one from his publisher. I do not know if Rascoe bothered to write back, but if he idd it does not seem to have been particularly encouraging. Thayer never came out with the booklet.

As Thayer’s work reviving the the Fortean Society continued, he came into conflict with Dreiser over the ownership of Fort’s notes; Dreiser’s lawyer looked into the matter, asking various Founders what they knew of the proceedings. Rascoe was sour on the whole matter. Writing in July 1937 from his mother’s home in Burlingame, California, he called Thayer a “stubborn brat”: “As far as I was ever able to figure out the Fortean Society was a phoney organization, without dues, officers, members, meeting place or charter and was merely a scheme devised by the fertile publicity brain of Tiffany Thayer for the promotion of the sale of Charles Fort’s books and publicizing his name. It was my impression also that this was a disinterested labor of love with Thayer, for which he received no fee either from Fort or Fort’s publishers and that Thayer bore all the expense (not much, I should judge) . . . Thayer made up his list of ‘founders’ simply by learning the names of some of the well-known writers and [other] personages who enjoyed Fort’s work and were quite willing that their name should be used in any legitimate way to promote the sale of Fort’s books.”

The meeting was the only time he met Fort, he said. Thayer had talked at the time time to hire a secretary to transcribe and arrange Fort’s notes but those were nothing more than “clippings of silly whoppers from provincial newspapers all over the world . . . and that without Fort’s genius, as a writer, in the selective use of this data, it is just so much trash.” Which was his general opinion of the Fortean Society: “The question in your mind seems, unfathomably to me, to be whether the Fortean Society is defunct or still functioning. In the manner you mean, it never did function; for there never was any Fortean Society except as a figment of Thayer’s fancy.”

Heedless of the controversy he was causing, Thayer went forward, and dragged Rascoe’s name with him. He was one of the official Founders, and received the magazine for years and years; I do not know that Rascoe read them, though he did save them, and they ended up with his papers.

Thayer started bothering Rascoe about the Society again in 1940, just before the omnibus edition of Fort’s books came out. In January, he sent Rascoe his life membership card in the Society, and pleaded with him to write a thousand words on Fort for the next issue. If Rascoe couldn’t write something new, Thayer offered to dig up something old—he thought Rascoe might have written something for the magazine “Arts & Decorations.” He also asked Rascoe to lunch.

Again, nothing seems to have come from the overture, for in November Thayer wrote again, asking for the write-up on Fort and announcing the omnibus edition would be out the following year. He needed Rascoe’s piece “now.” To sugar the pot, he offered a compliment of a piece Rascoe had recently written on publishers. Still nothing. In April 1941, a few weeks after the omnibus edition came out, Thayer begged, “I know you’re busy, my lad, but you gotta give the Fort omnibus a send-off somewhere. . . Please get into print on the subject in as many spots as possible. I had Holt send your copy direct.” For reasons hard to understand, Thayer was certain Rascoe would come through and, on the same date, wrote to Tarkington saying Rascoe was in for promoting The Books. But as far as I know, he never wrote anything about Fort, nor did he respond to Thayer.

Proof of sorts of Rascoe’s ignoring everything came later in 1941. The Fortean magazine—not yet called Doubt—dated October 1941 featured Rascoe’s thoughts on Fort; this was part of Thayer’s series on the Founders, which included their writings on Fort—what remains of this plan to make the publicity pamphlet, it would seem. It had nothing from “Arts & Decorations” and nothing new. Rather, it was a reprint of Rascoe’s review of “Lo!” with “The Books of Charles Fort” inserted where “Lo!” had once been, and the excision of two sentences that implied Fort was still alive. It also mis-spelled one of the words from the original review. Rascoe was clearly not interested in Fort anymore, and seemingly never much interested in the Fortean Society.

Still, Thayer kept up the pretense. In 1951, when Thayer was considering making Fortean opposition to Civilian Defense, by running an ad for the Society that announced it as so, he sent letters canvassing the opinion of all the Founders. In the end, the Founders chose not to proceed with the plans. But rancor was likely not one of those to even voice an opinion. He did get a letter, and it is still preserved in the archives. But it into be doubted that he bothered saying anything.

He had long ago given up on Fort and the Society founded in his name.