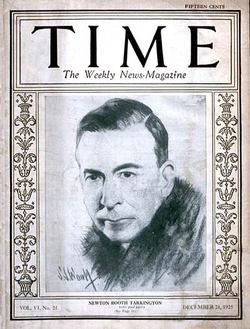

One of the Founders of the Fortean Society. Sorta. An immensely popular author in his time, now mostly forgotten.

Newton Booth Tarkington was born in Indianapolis on 29 July 1869—the same generation as Fort himself, then (b. 1874), and the oldest of the Founders of the Fortean Society. Tarkington came from patrician stock. His father. John S. Tarkington, was a lawyer with political leanings, serving in the Indiana General Assembly, organizing the 132nd Indiana Volunteers during the Civil War, and acting as a judge on the Fifth Circuit Court for a time. His mother was Elizabeth Booth, and her brother was a senator from and governor of California. Booth—as he would come to be called—had an older sister, Mary, born in 1861, who went by the nickname Haute.

Tarkington came to reflect many of the Gilded Age values then being forged—even as he struggled against Victorian-era morals. He attended high school, first, at a local public school, and when he was 14 his family became fascinated by Spiritualism. He would remain tolerant of psychic phenomena and communion with the dead, although the family’s religion seemed to settle more on a kind of Unitarianism—different from his paternal grandfather, who had been a Methodist preacher.

Newton Booth Tarkington was born in Indianapolis on 29 July 1869—the same generation as Fort himself, then (b. 1874), and the oldest of the Founders of the Fortean Society. Tarkington came from patrician stock. His father. John S. Tarkington, was a lawyer with political leanings, serving in the Indiana General Assembly, organizing the 132nd Indiana Volunteers during the Civil War, and acting as a judge on the Fifth Circuit Court for a time. His mother was Elizabeth Booth, and her brother was a senator from and governor of California. Booth—as he would come to be called—had an older sister, Mary, born in 1861, who went by the nickname Haute.

Tarkington came to reflect many of the Gilded Age values then being forged—even as he struggled against Victorian-era morals. He attended high school, first, at a local public school, and when he was 14 his family became fascinated by Spiritualism. He would remain tolerant of psychic phenomena and communion with the dead, although the family’s religion seemed to settle more on a kind of Unitarianism—different from his paternal grandfather, who had been a Methodist preacher.

Tarkington showed an early interest in theater, writing plays with Indiana friends, memorizing Shakespeare. He was a desultory student, though, and his mother sent him to the exclusive Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire to finish his high schooling. His biographer has it, “Two years at an Eastern school revived his interest in studies, toughened him mentally and emotionally, and removed him from the smothering attentions of his mother and sister.” His uncle Newton was paying for part of the education, too, which further impressed on Tarkington the need to be diligent.

Returned to Indiana, Tarkington played the part of the dandy about town, wearing clothes fashionable in the East (although ridiculed in Indiana), taking art classes, smoking, and chasing girls while his family tried to reacquire the fortune lost during the depression of the 1870s. (His father worked at a bank, source of a more stable income than a solo law practice.) His mother wanted Tarkington to attend Princeton, but he followed a girl to Purdue, which he attended for a year before the family’s finances recovered and his mother’s wishes won out. He started at Princeton in the fall of 1891.

Unpretentious and gay, Tarkington was welcomed into Princeton’s social scene. He edited three different magazines, including the school’s literary and humor journals. He belonged to the Ivy Club, an Eating Club, through which he may have met Woodrow Wilson, future president. By accounts, Tarkington was brilliant, and could pass his classes easily, without study, giving him ample time to devote to theater and literary avocations. According to Wikipedia, he was voted “most popular” student by the class of 1893, but didn’t graduate, coming up one class short. According to his biographer, his prose at this time was mostly undistinguished, but showed his developing style, in the tradition of William Dean Howells and American literary realists.

Tarkington set to work refining this style through the 1890s. He had returned to Indiana (again), where the family’s fortunes were looking up. Haute married in 1886, Booth was no longer in college, and his uncle had bequeathed him a small amount of money upon his death in 1892—enough to satisfy Tarkington’s need for cigarettes, booze, and ample time to write. He wrote plays and poems, did drawings, and worked on novels throughout this time, many of the works melodramas or historical romances, which were very popular at the time. For the most part, his family was indulgent—indeed, in retirement, his father would take to writing as well. But Tarkington could not break through any more than the local press for most of the decade, manuscripts returning from New York, his biographer said, so fast it seems that they must have been intercepted in Philadelphia. But Tarkington was a man blessed with an amazing depth of good humor, which he drew upon and drank to fortify him through these rejections and the sideward glances of his (seemingly) more industrious neighbors.

His breakthrough came in 1899, with the acceptance and publication of The Gentleman from Indiana, which he had been writing since his return from Princeton. That got him to New York, for a time, where he edited the manuscript, and New orleans, where he became secretly engaged. He had another book out in 1900, Monsieur Beaucaire, also set in Indiana. By this time, the engagement was off. He found his way back to Indiana, marrying in 1902 and, that same year, running for and winning office: he had inherited some of his family’s public spiritidness and felt it his duty as a gentleman to serve in the government. It also served his chosen career, providing material for In the Arena, but by this point Tarkington was an old hand at publishing, having put out three other novels and a book of poetry in the meantime. These were relatively light fare, and showed his valuation of comedy over tragedy.

The world opened itself to Tarkington. He traveled much, through New York and across Europe. He made fast friends with Harry Leon Wilson, another future Fortean, and together they wrote plays. Tarkington and his wife, Wilson and his, resided cheek by jowl in Europe, where the drinking was heavy and the living easy. He continued to publish novels and, on a return to America, he and Wilson launched their first and most remembered play “The Man from Home.” Tarkington continued traveling the country—working the “Road,” as the small theater scene was called, collaborating with Wilson and indulging his vices. He started collecting art.

By 1911, though, the party was ending. His mother was two years dead. He was drinking too much. He was writing too little. Wilson and his wife had split years before, and now Tarkington’s own marriage unravelled. Hoosiers looked down on him, dissolute, cosmopolitan, more Bohemian than gentleman. He returned to Europe with some family members, and regained a bit of the old joie de vivre, but the divorce was still proceeding and, in the end, he would lose custody of his daughter for 11 months of every year. But he would put things right, too, with the help of a new love, Susanah Keifer Robinson. She had him kick the booze. He started writing again, in January of 1912, and they were married later that year. The next decade would see him achieve his greatest fame and write his most famous and celebrated novels. She took it as her duty to buffer Tarkington from quotidian demands and make certain the domestic machinery ran smoothly so that he could concentrate upon writing.

Some of his stories cast an idyllic, even nostalgic eye on life in the Midwest: the Penrod tales, beginning with the 1914 novel of that name, were about boyhood in the midlands. Seventeen was about young love in pre-War Midwest. These stood in the realist tradition, but were purposefully not seedy: there were only insinuations of sex, Tarkington more interested in other emotions. The worlds that Tarkington created were very different than those of his fellow Hoosier, Theodore Dreiser, who specialized in tragedy and tried to capture the lives of prostitutes and the indigent.

That is not to say Tarkington was all light; he had a bitter edge, too. The Gentlemen from Indiana was concerned about the destruction of the Midwest by industrialization. Smoke befouled the air; cars changed the pace of the city; electrical light changed its looks. His 1915 novel was titled The Turmoil, and became the first in what was called the Growth trilogy, documenting the environmental atrocities committed in the United States’s heartland. Novelist Thomas Mallon said,

“The automobile, whose production was centered in Indianapolis before World War I, became the snorting, belching villain that, along with soft coal, laid waste to Tarkington's Edens. His objections to the auto were aesthetic—in The Midlander (1923) automobiles sweep away the more beautifully named "phaetons" and "surreys"—but also something far beyond that. Dreiser, his exact Indiana contemporary, might look at the Model T and see wage slaves in need of unions and sit-down strikes; Tarkington saw pollution, and a filthy tampering with human nature itself. "No one could have dreamed that our town was to be utterly destroyed," he wrote in The World Does Move. His important novels are all marked by the soul-killing effects of smoke and asphalt and speed, and even in Seventeen, Willie Baxter fantasizes about winning Miss Pratt by the rescue of precious little Flopit from an automobile's rushing wheels.”

When War did finally come, Tarkington put his skills to national advantage, writing propaganda, even as he continued to bemoan the industrialization of the Midwest—and receive accolades for it. In 1918, his The Magnificent Ambersons—about the intersecting fortunes of old-money Midwesterners and parvenu industrialists—won the Pulitzer Prize. It was the second book in his Growth trilogy. He collaborated with Wilson again, although Wilson had by then settled in Carmel, California. Tarkington won the Pulitzer again in 1921, with Alice Adams. By that time he was like America’s best known author. In 1922, he received a fan letter from Alexander Woollcott, a future Fortean, member of the Algonquin Roundtable, and long-time fan. They would bond, especially, over another of Tarkington’s passions, dogs, particularly poodles. It was a love shared by Wilson, too. As he collected art, Tarkington would collect dogs. And he wrote about both: Gamin, a poodle, was a major part of his book Gentle Julia. He poked fun of aesthetic collections in his unserious The Collector's Whatnot: A Compendium, Manual, and Syllabus of Information and Advice on All Subjects Appertaining to the Collection of Antiques, Both Ancient and Not So Ancient. More awards and recognition followed: that literary apprenticeship in the ‘90s had paid off.

Amid the joys, though, there were sorrows. As he was writing propaganda for the government, he noticed that his eyesight was dimming, and his right hand weakened—problems that would persist and increase throughout the 1920s—like Fort, he almost became blind in the decade. Tarkington’s father died of pneumonia in January of 1923. Three months later, his daughter, Laurel, was visiting from Cambridge, Massachusetts (where her remarried mother lived) when she contracted pneumonia. It killed her after only a few days. Tarkington was heartbroken. After his mother ha died and he had returned to his old homestead at 1100 North Pennsylvania, Indianapolis, Tarkington felt surrounded “by the kindest ghosts in the world.” He saw Laurel’s ghost after her death—at least according to fellow Fortean R. DeWitt Miller—which offered him some degree of comfort, but the pain was too much. He finished the third book in the Growth Trilogy, The Midlander, and shortly thereafter moved to 4270 North Meridian. He continued to spend his summers in Kennebunkport, Maine, at a home he named Seaglass, with a boat and boathouse, secretary, and others, although it was quieter now, as Laurel had spent her summers there.

“But there was no happiness for Tarkington in anything but writing, and he went on using up his eyes and energy in unrelenting work for the balance of the decade. His total output of fiction eventually totaled forty-one volumes, plus dozens of stories and ten

serials and story sequences that never were put into book form; and during the period between writing Women, January, 1924, and the end of the decade he wrote twenty uncollected stories . . . At the end of 1924, however, Tarkington was temporarily weary and desirous of a long vacation. Accordingly, he planned for the following year his first Sabbatical leave from literature since he had settled down to serious writing and had produced The Flirt in 1912.”

The trip took him through North Africa, and then to Italy, where he was reminded, again, of Laurel, who had been born there in 1906.

In 1928, eyesight dimming, Tarkington published a memoir of sorts, The World Does Move. Excerpted in The Saturday Evening Post, The World Does Move starts out as the maundering contemplates of an aging man, albeit gracefully and carefully observed, complaining about electric lights, cars, the New Woman, and the tendency of modern writers to include too much graphic sex in their stories—a shot, it would seem, at his fellow Hoosier, Dreiser, and debunkers (here he was aiming at H. L. Mencken):

"On this altar, they said, everything old must be burned as incense; all believers in anything old were either fools or hypocrites and must be jeered to death. The new questioning, believing Science to be new, could therefore have faith in it--at least so long as it could be interpreted as maintaining the ancient theological theory of predestination now masquerading in the new phrase, 'mechanistic philosophy.' For, like the automobile and all the new machines men had invented for greater speed and for ease to labour, the fast-whirling universe itself must be, these new questioners argued, a machine.”

But the memoirs take a decidedly weird turn when Tarkington introduces a genuine fuddy-duddy, Judge Olds (surely a creation, and one reason, perhaps, Tarkington refused to call this a proper memoir) .Judge is exercised not only by these same changes, but especially by the rise of the so-called New Woman—smoking, unchaperoned, short-haired, and frank. Tarkington--or rather, the narrator, who seems to be Tarkington—finds himself defending women, and, ultimately, all the changes: Sure, there is a horrid fascination with sex stories--but this is just a craze, and soon the 'subject will takes its proper proportion.' (249). No, 'The ladies do not belong to us any more, and they don't all live for us and to "manage" us—not quite in the sense they used to. They've decided to live more for themselves." Yes, women spend a lot of money on their appearance, but in the eighteenth century it was men who preened in wigs and jewelry and perfume. This is convincing, and shows the narrator to be thoughtful—until he tries to win over the Judge by reading him a fantastic romance story about the end of Atlantis, in which it is proffered that men destroyed that fabled land rather than have women become dominant. I am not sure what to make of this--not the supposed moral of the story, but the presentation. Was this meant to be ironic, funny, satirical—of whom?

At any rate, the story does illustrate Tarkington's point--that the world moves, and it does not do so as a pendulum, but as an 'ascending spiral.' (280). Parts of the past are recycled, and new inventions made: each age its own fashions, and the narrator cannot begrudge the new generation its sense of its self, anymore than he should not have been moved by the delicious claim of the fin de siecle being the end of history. The older generation can objectively see some of what the newer has lost--the new, he could see, were no longer interested in refinement because refinement was a quality of leisure, and the world, moving faster, had little time for leisure (290)—but the new could build things the older generation could not even imagine.

His conclusion, therefore, is more subtle than the opening—or even the first three-quarters—would suggest. There is reason to be critical of the new age, for they too often forget the past altogether, but they also can create works and ideas previously unimaginable, if they attend the past, and the world can continue its upward spiral: "For every new age has at its disposal everything that was fine in all past ages, and its greatness depends upon how well it recognizes and preserves and brings to the aid of its own enlightenment whatever worthy and true things the dead have left on earth behind them' (294).

Approaching sixty, contemplating his own blindness, Tarkington had settled somewhat, though his acceptance of the new order came with an increasing conservatism. The social ills that had once bothered him no longer did—in part, because he was protected from them, his new home in Indianapolis farther from the factories, his second home giving him reprieve from even that. The world worked itself out—there was no need for intervention. A fifth surgery, this one in January 1931, finally fixed his eyesight. Tarkington was also buffered from the Great Depression, his wealth not declining—and, indeed, the economic downturn allowed him to increase his art collection, since others were willing to see on the cheap—and so when FDR was elected president and the New Deal was announced, he was a staunch and vocal advocate. He did come to his country’s aid with the on-set of World War II, though, again writing propaganda—as Woollcott did. His growing conservatism, then, was one shared by others of the founders as they aged: Ben Hecht also became something of a cranky right-winger and Zionist in the 1940s.

By the 1930s, his best years lay behind him. He continued to right throughout the period, but was probably best known because a number of his stories were adapted for film. He himself had given up on such adaptations in the mid-1920s, in part because of his declining eyesight, but also in part because (unlike Fort) he thought movies were faddish and insubstantial. He would suffer a steep decline in his literary fortunes, barely remembered today, despite his earlier popularity and critical acclaim. (Wilson underwent a similar plummet in reputation.) His material fortune, though, remained, and he was loyal to old friends. Tarkington was one of the few people Woollcott never alienated, his affability an armor against Woollcott’s occasional vitriol. Harry Wilson’s health declined substantially in the 1930s, and he had used up all the money he made: Tarkington frequently sent Wilson and his two children funds for medical treatments as well as just to keep the household going. When Wilson’s son, Leon, was imprisoned for refusing the draft—putting him at odds with Tarkington politically—the older writer still offered him material and moral and support, for which the younger Wilson was immensely grateful.

Booth Tarkington died 19 May 1946.

The relationship between Tarkington and Forteanism is fairly well documented. Likely, he read Fort first in late January or early February 1920, only a few months after The Book of the Damned was published (December 1920). He said that he read it when he had the flu and was forced to bed, and he noted just such an illness in a letter to Harry Leon Wilson dated 8 February 1920. In October, he sent a box of material to Wilson, likely including a copy of Fort—and thus turning Wilson onto Fort, though not in the manner suggested by science fiction fan Sam Moskowitz, who had Tarkington inducing Wilson to read Fort and then incorporating ideas from The Book of the Damned in his novel The Wrong Twin (the chronology of which is impossible. since the Wrong Twin started its serialization in November 1919).

Tarkington would write (in the foreword to Fort’s second book),

“A few years ago I had one of those pleasant illnesses that permit the patient to read in bed for several days without self-reproach; and I sent down to a bookstore for whatever might be available upon criminals, crimes and criminology. Among the books brought me in response to this morbid yearning was one with the title, The Book of the Damned.

I opened it, not at the first page, looking for Cartouche Jonathan Wild, Pranzini, Lacenaire, and read the following passage:

‘The fittest survive.

What is meant by the fittest?

Not the strongest; not the cleverest--

Weakness and stupidity everywhere survive.

There is no way of determining fitness except in that a thing does survive.

“Fitness” then, is only another name for “survival.’”

Finding no Guiteau or Troppmann here, I let the pages slide under my fingers and stopped at this:

‘My own pseudo-conclusion:

That we’ve been damned by giants sound asleep, or by great scientific principles and abstractions that cannot realize themselves: that little harlots have visited their caprices upon us; that clowns, with buckets of water from which they pretend to cast thousands of good-sized fishes have anathemized [sic] us for laughing because, as with all clowns, underlying buffoonery is the desire to be taken seriously; that pale ignorances, presiding over microscopes by which they cannot distinguish flesh from nostoc or fishes’ spawn or frogs’ spawn, have visited upon us their wan solemnities. We’ve been damned by corpses and skeletons and mummies, which twitch and totter with pseudo-life derived from conveniences.’

With some astonishment, I continued to dip into the book, sounding it here and there, but did not bring up even so well-damned a sample of the bottom as Benedict Arnold. Instead I got these:

‘An object from which nets were suspended--

Deflated ballon with its network hanging from it--

A super-dragnet?

That something was trawling overhead?

The birds of Baton Rouge.

I think that we’re fished for. It may be were highly esteemed by super-epicures somewhere.

‘. . . Melancius.

That upon the wings of a super-bat, he broods over this earth and over other worlds, deriving something from them: hovers on wings or wing-like appendages, or planes that are hundreds of miles from tip to tip--a super-evil thing that is exploiting us. By evil I mean that which makes us useful.’

‘. . . British India Company’s steamer Patna, while on a voyage up the Persian Gulf. In May, 1880, on a dark night about 11:30 P.M. there suddenly appeared on each side of the ship an enormous luminous wheel, whirling around, the spokes of which seemed to brush the ship along . . . and although the wheels must have been 500 or 600 yards in diameter, the spokes could be distinctly seen all the way round.’

‘. . . . I shall have to accept that, floating in the sky of this earth, there are often fields of ice as extensive as those on the Arctic Ocean--volumes of water in which are many fishes and frogs--tracts of land covered with caterpillars--’

‘ . . . Black rains--red rains--the fall of a thousand tons of butter.

Jet black snow--pink snow--blue hailstones--hailstones flavored like oranges.

Punk and silk and charcoal.’

‘ . . . A race of tiny beings.

They crucified cockroaches.

Exquisite beings—’

(This description undermines Moskowitz’s claim that Tarkington picked up The Book of the Damned thinking it was a murder mystery.)

Tarkington was a professional humorist, and he could see Fort was very funny; he was also interested in art—and he could see Fort’s artistry, too, finding in him an echo of the Romantic and Weird artists of the nineteenth century:

“But here I turned back to the beginning and read this vigorous and astonishing book straight through, and then re-read it for the pleasure it gave me in the way of its writing and in the substance of what it told. Dorè should have illustrated it, I thought, or Blake. Here indeed was a ‘brush dipped in earthquake and eclipse’; though the wildest mundane earthquakes are but earthquakes in teapots compared to what goes on in the visions conjured up before us by Mr. Charles Fort. For he deals in nightmare, not on the planetary, but on the constellational scale, and the imagination of one who staggers along after him is frequently left gasping and flaccid.”

Tarkington was so moved that he opened a letter about the book to The Bookman—or so it seems. The actual reason for him sending the letter is not quite clear. Most people who have heard of this letter have sourced it to Thayer (who gave an unclear source of it); even Tarkington’s bibliographers had trouble finding the original publication. I did eventually track it down to an August 1920 issue, where it appeared in the back matter, among the advertising, and where Tarkington’s identity was not given but was so badly disguised it might as well have been. All of this background is very confusing, and I am not sure what to make of the letter—other than Tarkington was singing Fort’s praises in a voice similar to the one he would use a few years later:

“A gentleman, writer of fiction by profession, whose name is a ‘household word’ in every home in the land and who lives not far from the most celebrated ‘soldiers’ monument’ in the United States, writes Gossip Shop as follows:

Who in the name of frenzy is Charles Fort? Author of The Book of the Damned. I’m just pulling from influenza and this blamed book kept me all night when I certainly should have slept--and then, in the morning, what is a fevered head to do with assemblies of worlds, some shaped like wheels, some connected by streaming filaments, and one spindle shaped with an axis 100,000 miles long?

A clergyman, old brilliant friend of mine, ‘went insane’ one summer--got over it when his wife got home from Europe but that summer he was gone. I remember when I caught him: he spent all of a hot afternoon telling me, at the University Club, about a secret society of the elect--adepts--who had since days immemorial welcomed (and kept hidden) messages from other planets. That’s where this alleged Charles Fort shows his bulliest dementia--but he’s ‘colossal’--a magnificent nut, with Poe and Blake and Cagliostro and St. John trailing way behind him. And with a gorgeous madman’s humor! What do you know of him? And doesn’t he deserve some BOOKMAN attention? (I never heard of the demoniac cuss.) People must turn to look at his head as he walks down the street; I think it’s a head that would emit noises and explosions, with copper flames playing out from the ears.”

Presumably Tarkington was not aware of Fort because of his distance from Dreiser, who had known of the Bronx philosopher for more than a decade. Also presumably, there was some correspondence between Tarkington and Fort, or at least Tarkington and Fort’s publisher, Boni & Liveright, and Tarkington was pleased enough with Fort’s sense of humor that he agreed to write the preface to Fort’s second book, 1923’s New Lands. The beginning of that preface is quoted above. It then moves on to discuss the book at hand:

Now he has followed ‘The Book of the Damned’ with ‘New Lands’ pointing incidentally to Mars as ‘the San Salvador of the Sky,’ and renewing his passion for the dismayingly significant ‘damned’--tokens and strange hints excluded by the historically mercurial acceptance of ‘Dogmatic Science.’ Of his attack on the astronomers it can at least be said that the literature of indignation is enriched by it.

To the ‘university-trained mind’ here is wildness almost as wild as Roger Bacon’s once appeared to be; though of course even the layest of lay brothers must not assume that all wild science will in time become accepted law, as some of Roger’s did. Retort to Mr. Fort must be left to the outraged astronomer, if indeed any astronomer could feel himself so little outraged as to offer retort. Lay brethren are outside the quarrel and must content themselves with gratitude to a man who writes two such books as ‘New Lands’ and ‘The Book of the Damned’; gratitude for passages and pictures--moving pictures--of such cyclonic activity and dimensions that a whole new area of reader’s imagination stirs in amazement and is brought to life.”

Tarkington, here, is distancing himself, somewhat, from Fort’s most outspoken book, one in which he moved furthest from skepticism and posited his own astronomy. Tarkington was likely skeptical enough of science—what with his acceptance of spiritualism and his disdain for industry and materialism—to nod along with most of what Fort said. Still, it seems that his main reason for liking Fort was the humor—one could read Fort in the same way one could read Tarkington’s own book on collecting published around the same time: both were satires. The introduction further suggests some correspondence between Tarkington and Fort, as Tarkington sees the cinematic qualities of Fort’s writings, and comments upon them—and Fort himself would later tell Maynard Shipley that he thought his books a response to films, which he figured would replace literary fiction. But if there was any correspondence, it has been lost lo these many years.

It was around this time that Tarkington introduced Fort to Alexander Woollcott. The exact sequence of events is unknown—Woollcott mentions it in passing in a later article on Fort and the Fortean Society—and there is no correspondence between the two men at this time. Perhaps Tarkington mentioned Fort to Woollcott in person, one time when traveling through New York; or perhaps Woollcott was attracted to Fort’s second book by noticing Booth Tarkington wrote the foreword and, being a fan of Tarkington, picked up the book and found his way to Fort.

Fort was still on Tarkington’s mind as of June 1930—seven years after Fort’s last book, and despite Tarkington’s blindness. The sourcing here is not as good as I would like—the quotation comes from Thayer, although the citation is corroborated by Tarkington’s bibliographer. It’s from “Booth Tarkington Recalls: That It Is Very Difficult to Be Unorthodox Concerning a Piano,” New York Sun June 19, 1930:

“Few of us nowadays have the wit or the temerity of Mr. Charles Fort. ‘Granted that there will be posterity,’ Mr. Fort says in his book New Lands, ‘we shall have predecessors. Then what is it that is conventionally taught today that will in the future seem as imbecilic as to all present orthodoxies seem the vaporings of preceding systems?

‘Well, for instance, that it is this earth that moves . . .’

Mr. Fort speaks convincingly of the ‘swiftly moving sun,’ and he notices ‘successive appearances in local skies of this earth that indicate this earth is stationary.’

Mr. Fort, however, as the title of his book implies, is less interested in this unmoving earth than in the new lands that move or are rigidly set in the sky. ‘A Balboa of greatness now known only ti himself will stand on a ridge in the sky between two auroral seas.

‘Fountains of Everlasting Challenge.

‘Argosies in parallel lines and rabbles of individual adventurers. Well enough may it be said that there are seeds in the sky. Of such are the germs of colonies.’

Mr. Fort would have the young man of today go not West but Up. ‘He will, or must, go somewhere,’ he says. ‘If directions alone no longer invite him, he may hear invitation in dimensions. . . . Stay and let salvation damn you--or straddle an aurorial beam and paddle it from Rigel to Betelgeuse.’

Any one who is interested in unorthodoxics, who is ‘fair-minded,’ who enjoys having his imagination staggered and his mind dazzled by visions of a future on the constellational scale, should read Mr. Charles Fort’s vigorous and astonishing books: New Lands and The Book of the Damned.”

A year-and-a-half later, Thayer (at J. David Stern’s urging) was organizing the Fortean Society as a way to promote Fort’s third book, written after the return of his own eyesight: Lo! Tarkington was among the earliest of the founders listed—included in press releases before some of the others, such as Alexander Woollcott. Presumably there was some correspondence about this, but it is lost. And he doesn’t seem to have shared any initial thoughts on the matter with Wilson or Woollcott. There is a large gap in the correspondence at this time; Wilson said it was because he was so afraid to learn that Tarkington’s blindness was permanent. In 1937, he told Wilson how his connection to the Society came about (and confirmed that there had been correspondence between him and Fort):

“Years ago some people, no acquaintances of mine and [] this T.T. formed the “Fortean Soc.” and I signed up by mail, as understood the purpose was to be of use to that extraordinary man, Charles Fort, attract notice to his writings by giving a dinner for him, etc. (Fort was a great fellow--disappointed in me because it was a more literary than scientific interest in his works, he wrote me he’d discovered a terrific gulf in some constellation, a trillion mile vacuum, and had named it ‘Tarkington Gulf.’) I never saw [a]live; he used to live with Dreiser.”

Tarkington did allow his name to be used on the Fortean Society propaganda, but he did not appear at the initial meeting, in January 1931. At that time he was recovering from the fifth surgery on his eyes—the successful one. Nor was he particularly impressed with Lo!, which he read in April 1931. He told Wilson it lacked the effervescence of Fort’s earlier two books. If he read Wild Talents, his reaction is unrecorded and his interest in Fort seems as though it would have disappeared, were it not for Thayer and insistence on resuscitating the Society. In 1937, Thayer was in a fight with Fort’s widow and Dreiser over ownership of Fort’s notes, a fight that involved the lawyer Arthur Leonard Ross, who wrote to the founders of the Fortean Society about their understanding of the Society and its intents. Tarkington said that as far as he knew, the Society died with Fort. “I am entirely puzzled by Mr. Thayer’s action in the matter,” he wrote, “and can’t imagine on what ground he stands.”

Thayer, though, did win that fight and started printing the notes in his new magazine devoted to Forteanism. Thayer made certain that the founders all received a copy of the first issue (a letter informing Tarkington of the issue’s publication survives in Tarkington’s papers). The cranky content was a turn-off to Tarkington’s more conservative friends, and after the first issue was sent out he received a letter from one: “Are you honest + truly a founder of the Fortean Society, which seems to include me on its mailing? If so, would you advise me just what the purpose of this organization is--humor, pseudomystification, or a new way of collecting $2 from curious humans. Perhaps the magazine is the house organ of some insane asylum. I give up guessing.” Tarkington’s response to Thayer’s publication was silence—which seems to be significant. In his letter announcing the magazine, Thayer had asked Tarkington for more statements on Fort, but none were ever printed, suggesting Tarkington didn’t bother.

Indeed, his entire strategy seems to have been to ignore Thayer and hope he went away. In a letter to Wilson, he acted to disassociate himself from the whole mater: “Hasten to dispense any suspicions you may have about my friendship for, or with, Mr. Tiffany T. Never see the bird.” After recounting how he came to be attached to the Fortean Society, he continued, Well, this summer Mrs. Fort’s lawyer (Fort’s widow’s) wrote me T.T, withheld all of Fort’s papers--said they belonged to the Fortean Soc. and wouldn’t turn ‘em in--and asked me (the lawyer did) to make a statement that the Soc. was extinct and the widow should have the papers. I did. Heard nothing more until rec’d copy of the 1st number of the mag, which brought me some letters from []. No correspondence with T.T., who seems to be using me pretty freely. He’ll blow up pretty soon, I’d think, Evidently use of the horse [‘s] daughter.” (Tarkington’s handwriting is horrible, and the parentheses represent words I could not decipher.)

Tarkington continued to ignore Thayer, even as Thayer used his name (and his excerpts on Fort) in his magazine and promotion of the Fortean Society. In 1941, with the publication of Fort’s omnibus edition, Thayer wrote Tarkington again, asking him t do something to promote the book—maybe in The Saturday Evening Post. Again, there’s no evidence that Tarkington responded to the letter or wrote up anything on Fort. A few years later, J. David Stern alerted the FBI to Thayer’s effusions, finding them seditious and wanting to be assured that he—and the other founders—would not be associated with Thayer’s actions. He received a memo from the FBI acknowledging that Thayer’s writings tended toward the seditious but, given the erratic publication schedule, there was no more need for investigation. Stern sent a copy of the memorandum to Tarkington and asked that he keep his eyes open lest Thayer use their name sin vain again.

There was some more correspondence between Thayer and Tarkington, but only a small bit of it survives. Apparently in 1943, Thayer wrote Tarkington requesting some kind of favor. That original letter and Tarkington’s response don’t seem to exist, but Thayer’s return letter does. He seems to imply that Tarkington wanted to be separated from the Fortean Society—at least, have no active work in it—which Thayer agreed to. (Tarkington’s name would continue to be used.) Thayer went on to thank Tarkington for remarking upon his sincerity—and there’s the affable Tarkington again, able to smooth over even egregious breaches of etiquette.

Besides the formal use of Tarkington’s name in the Fortean Society magazine and correspondence, and the one issue that reprinted all of Tarkington’s comments on Fort, his name only appeared one other time in the magazine. One assumes that is because Tarkington’s prestige dropped so much that there was little reason for Thayer to call attention to his love of Fort. That other mention was his passing, and that was only the briefest of notices. Thayer did offer an honorary lifetime membership to his wife Susanah, but she declined.

Returned to Indiana, Tarkington played the part of the dandy about town, wearing clothes fashionable in the East (although ridiculed in Indiana), taking art classes, smoking, and chasing girls while his family tried to reacquire the fortune lost during the depression of the 1870s. (His father worked at a bank, source of a more stable income than a solo law practice.) His mother wanted Tarkington to attend Princeton, but he followed a girl to Purdue, which he attended for a year before the family’s finances recovered and his mother’s wishes won out. He started at Princeton in the fall of 1891.

Unpretentious and gay, Tarkington was welcomed into Princeton’s social scene. He edited three different magazines, including the school’s literary and humor journals. He belonged to the Ivy Club, an Eating Club, through which he may have met Woodrow Wilson, future president. By accounts, Tarkington was brilliant, and could pass his classes easily, without study, giving him ample time to devote to theater and literary avocations. According to Wikipedia, he was voted “most popular” student by the class of 1893, but didn’t graduate, coming up one class short. According to his biographer, his prose at this time was mostly undistinguished, but showed his developing style, in the tradition of William Dean Howells and American literary realists.

Tarkington set to work refining this style through the 1890s. He had returned to Indiana (again), where the family’s fortunes were looking up. Haute married in 1886, Booth was no longer in college, and his uncle had bequeathed him a small amount of money upon his death in 1892—enough to satisfy Tarkington’s need for cigarettes, booze, and ample time to write. He wrote plays and poems, did drawings, and worked on novels throughout this time, many of the works melodramas or historical romances, which were very popular at the time. For the most part, his family was indulgent—indeed, in retirement, his father would take to writing as well. But Tarkington could not break through any more than the local press for most of the decade, manuscripts returning from New York, his biographer said, so fast it seems that they must have been intercepted in Philadelphia. But Tarkington was a man blessed with an amazing depth of good humor, which he drew upon and drank to fortify him through these rejections and the sideward glances of his (seemingly) more industrious neighbors.

His breakthrough came in 1899, with the acceptance and publication of The Gentleman from Indiana, which he had been writing since his return from Princeton. That got him to New York, for a time, where he edited the manuscript, and New orleans, where he became secretly engaged. He had another book out in 1900, Monsieur Beaucaire, also set in Indiana. By this time, the engagement was off. He found his way back to Indiana, marrying in 1902 and, that same year, running for and winning office: he had inherited some of his family’s public spiritidness and felt it his duty as a gentleman to serve in the government. It also served his chosen career, providing material for In the Arena, but by this point Tarkington was an old hand at publishing, having put out three other novels and a book of poetry in the meantime. These were relatively light fare, and showed his valuation of comedy over tragedy.

The world opened itself to Tarkington. He traveled much, through New York and across Europe. He made fast friends with Harry Leon Wilson, another future Fortean, and together they wrote plays. Tarkington and his wife, Wilson and his, resided cheek by jowl in Europe, where the drinking was heavy and the living easy. He continued to publish novels and, on a return to America, he and Wilson launched their first and most remembered play “The Man from Home.” Tarkington continued traveling the country—working the “Road,” as the small theater scene was called, collaborating with Wilson and indulging his vices. He started collecting art.

By 1911, though, the party was ending. His mother was two years dead. He was drinking too much. He was writing too little. Wilson and his wife had split years before, and now Tarkington’s own marriage unravelled. Hoosiers looked down on him, dissolute, cosmopolitan, more Bohemian than gentleman. He returned to Europe with some family members, and regained a bit of the old joie de vivre, but the divorce was still proceeding and, in the end, he would lose custody of his daughter for 11 months of every year. But he would put things right, too, with the help of a new love, Susanah Keifer Robinson. She had him kick the booze. He started writing again, in January of 1912, and they were married later that year. The next decade would see him achieve his greatest fame and write his most famous and celebrated novels. She took it as her duty to buffer Tarkington from quotidian demands and make certain the domestic machinery ran smoothly so that he could concentrate upon writing.

Some of his stories cast an idyllic, even nostalgic eye on life in the Midwest: the Penrod tales, beginning with the 1914 novel of that name, were about boyhood in the midlands. Seventeen was about young love in pre-War Midwest. These stood in the realist tradition, but were purposefully not seedy: there were only insinuations of sex, Tarkington more interested in other emotions. The worlds that Tarkington created were very different than those of his fellow Hoosier, Theodore Dreiser, who specialized in tragedy and tried to capture the lives of prostitutes and the indigent.

That is not to say Tarkington was all light; he had a bitter edge, too. The Gentlemen from Indiana was concerned about the destruction of the Midwest by industrialization. Smoke befouled the air; cars changed the pace of the city; electrical light changed its looks. His 1915 novel was titled The Turmoil, and became the first in what was called the Growth trilogy, documenting the environmental atrocities committed in the United States’s heartland. Novelist Thomas Mallon said,

“The automobile, whose production was centered in Indianapolis before World War I, became the snorting, belching villain that, along with soft coal, laid waste to Tarkington's Edens. His objections to the auto were aesthetic—in The Midlander (1923) automobiles sweep away the more beautifully named "phaetons" and "surreys"—but also something far beyond that. Dreiser, his exact Indiana contemporary, might look at the Model T and see wage slaves in need of unions and sit-down strikes; Tarkington saw pollution, and a filthy tampering with human nature itself. "No one could have dreamed that our town was to be utterly destroyed," he wrote in The World Does Move. His important novels are all marked by the soul-killing effects of smoke and asphalt and speed, and even in Seventeen, Willie Baxter fantasizes about winning Miss Pratt by the rescue of precious little Flopit from an automobile's rushing wheels.”

When War did finally come, Tarkington put his skills to national advantage, writing propaganda, even as he continued to bemoan the industrialization of the Midwest—and receive accolades for it. In 1918, his The Magnificent Ambersons—about the intersecting fortunes of old-money Midwesterners and parvenu industrialists—won the Pulitzer Prize. It was the second book in his Growth trilogy. He collaborated with Wilson again, although Wilson had by then settled in Carmel, California. Tarkington won the Pulitzer again in 1921, with Alice Adams. By that time he was like America’s best known author. In 1922, he received a fan letter from Alexander Woollcott, a future Fortean, member of the Algonquin Roundtable, and long-time fan. They would bond, especially, over another of Tarkington’s passions, dogs, particularly poodles. It was a love shared by Wilson, too. As he collected art, Tarkington would collect dogs. And he wrote about both: Gamin, a poodle, was a major part of his book Gentle Julia. He poked fun of aesthetic collections in his unserious The Collector's Whatnot: A Compendium, Manual, and Syllabus of Information and Advice on All Subjects Appertaining to the Collection of Antiques, Both Ancient and Not So Ancient. More awards and recognition followed: that literary apprenticeship in the ‘90s had paid off.

Amid the joys, though, there were sorrows. As he was writing propaganda for the government, he noticed that his eyesight was dimming, and his right hand weakened—problems that would persist and increase throughout the 1920s—like Fort, he almost became blind in the decade. Tarkington’s father died of pneumonia in January of 1923. Three months later, his daughter, Laurel, was visiting from Cambridge, Massachusetts (where her remarried mother lived) when she contracted pneumonia. It killed her after only a few days. Tarkington was heartbroken. After his mother ha died and he had returned to his old homestead at 1100 North Pennsylvania, Indianapolis, Tarkington felt surrounded “by the kindest ghosts in the world.” He saw Laurel’s ghost after her death—at least according to fellow Fortean R. DeWitt Miller—which offered him some degree of comfort, but the pain was too much. He finished the third book in the Growth Trilogy, The Midlander, and shortly thereafter moved to 4270 North Meridian. He continued to spend his summers in Kennebunkport, Maine, at a home he named Seaglass, with a boat and boathouse, secretary, and others, although it was quieter now, as Laurel had spent her summers there.

“But there was no happiness for Tarkington in anything but writing, and he went on using up his eyes and energy in unrelenting work for the balance of the decade. His total output of fiction eventually totaled forty-one volumes, plus dozens of stories and ten

serials and story sequences that never were put into book form; and during the period between writing Women, January, 1924, and the end of the decade he wrote twenty uncollected stories . . . At the end of 1924, however, Tarkington was temporarily weary and desirous of a long vacation. Accordingly, he planned for the following year his first Sabbatical leave from literature since he had settled down to serious writing and had produced The Flirt in 1912.”

The trip took him through North Africa, and then to Italy, where he was reminded, again, of Laurel, who had been born there in 1906.

In 1928, eyesight dimming, Tarkington published a memoir of sorts, The World Does Move. Excerpted in The Saturday Evening Post, The World Does Move starts out as the maundering contemplates of an aging man, albeit gracefully and carefully observed, complaining about electric lights, cars, the New Woman, and the tendency of modern writers to include too much graphic sex in their stories—a shot, it would seem, at his fellow Hoosier, Dreiser, and debunkers (here he was aiming at H. L. Mencken):

"On this altar, they said, everything old must be burned as incense; all believers in anything old were either fools or hypocrites and must be jeered to death. The new questioning, believing Science to be new, could therefore have faith in it--at least so long as it could be interpreted as maintaining the ancient theological theory of predestination now masquerading in the new phrase, 'mechanistic philosophy.' For, like the automobile and all the new machines men had invented for greater speed and for ease to labour, the fast-whirling universe itself must be, these new questioners argued, a machine.”

But the memoirs take a decidedly weird turn when Tarkington introduces a genuine fuddy-duddy, Judge Olds (surely a creation, and one reason, perhaps, Tarkington refused to call this a proper memoir) .Judge is exercised not only by these same changes, but especially by the rise of the so-called New Woman—smoking, unchaperoned, short-haired, and frank. Tarkington--or rather, the narrator, who seems to be Tarkington—finds himself defending women, and, ultimately, all the changes: Sure, there is a horrid fascination with sex stories--but this is just a craze, and soon the 'subject will takes its proper proportion.' (249). No, 'The ladies do not belong to us any more, and they don't all live for us and to "manage" us—not quite in the sense they used to. They've decided to live more for themselves." Yes, women spend a lot of money on their appearance, but in the eighteenth century it was men who preened in wigs and jewelry and perfume. This is convincing, and shows the narrator to be thoughtful—until he tries to win over the Judge by reading him a fantastic romance story about the end of Atlantis, in which it is proffered that men destroyed that fabled land rather than have women become dominant. I am not sure what to make of this--not the supposed moral of the story, but the presentation. Was this meant to be ironic, funny, satirical—of whom?

At any rate, the story does illustrate Tarkington's point--that the world moves, and it does not do so as a pendulum, but as an 'ascending spiral.' (280). Parts of the past are recycled, and new inventions made: each age its own fashions, and the narrator cannot begrudge the new generation its sense of its self, anymore than he should not have been moved by the delicious claim of the fin de siecle being the end of history. The older generation can objectively see some of what the newer has lost--the new, he could see, were no longer interested in refinement because refinement was a quality of leisure, and the world, moving faster, had little time for leisure (290)—but the new could build things the older generation could not even imagine.

His conclusion, therefore, is more subtle than the opening—or even the first three-quarters—would suggest. There is reason to be critical of the new age, for they too often forget the past altogether, but they also can create works and ideas previously unimaginable, if they attend the past, and the world can continue its upward spiral: "For every new age has at its disposal everything that was fine in all past ages, and its greatness depends upon how well it recognizes and preserves and brings to the aid of its own enlightenment whatever worthy and true things the dead have left on earth behind them' (294).

Approaching sixty, contemplating his own blindness, Tarkington had settled somewhat, though his acceptance of the new order came with an increasing conservatism. The social ills that had once bothered him no longer did—in part, because he was protected from them, his new home in Indianapolis farther from the factories, his second home giving him reprieve from even that. The world worked itself out—there was no need for intervention. A fifth surgery, this one in January 1931, finally fixed his eyesight. Tarkington was also buffered from the Great Depression, his wealth not declining—and, indeed, the economic downturn allowed him to increase his art collection, since others were willing to see on the cheap—and so when FDR was elected president and the New Deal was announced, he was a staunch and vocal advocate. He did come to his country’s aid with the on-set of World War II, though, again writing propaganda—as Woollcott did. His growing conservatism, then, was one shared by others of the founders as they aged: Ben Hecht also became something of a cranky right-winger and Zionist in the 1940s.

By the 1930s, his best years lay behind him. He continued to right throughout the period, but was probably best known because a number of his stories were adapted for film. He himself had given up on such adaptations in the mid-1920s, in part because of his declining eyesight, but also in part because (unlike Fort) he thought movies were faddish and insubstantial. He would suffer a steep decline in his literary fortunes, barely remembered today, despite his earlier popularity and critical acclaim. (Wilson underwent a similar plummet in reputation.) His material fortune, though, remained, and he was loyal to old friends. Tarkington was one of the few people Woollcott never alienated, his affability an armor against Woollcott’s occasional vitriol. Harry Wilson’s health declined substantially in the 1930s, and he had used up all the money he made: Tarkington frequently sent Wilson and his two children funds for medical treatments as well as just to keep the household going. When Wilson’s son, Leon, was imprisoned for refusing the draft—putting him at odds with Tarkington politically—the older writer still offered him material and moral and support, for which the younger Wilson was immensely grateful.

Booth Tarkington died 19 May 1946.

The relationship between Tarkington and Forteanism is fairly well documented. Likely, he read Fort first in late January or early February 1920, only a few months after The Book of the Damned was published (December 1920). He said that he read it when he had the flu and was forced to bed, and he noted just such an illness in a letter to Harry Leon Wilson dated 8 February 1920. In October, he sent a box of material to Wilson, likely including a copy of Fort—and thus turning Wilson onto Fort, though not in the manner suggested by science fiction fan Sam Moskowitz, who had Tarkington inducing Wilson to read Fort and then incorporating ideas from The Book of the Damned in his novel The Wrong Twin (the chronology of which is impossible. since the Wrong Twin started its serialization in November 1919).

Tarkington would write (in the foreword to Fort’s second book),

“A few years ago I had one of those pleasant illnesses that permit the patient to read in bed for several days without self-reproach; and I sent down to a bookstore for whatever might be available upon criminals, crimes and criminology. Among the books brought me in response to this morbid yearning was one with the title, The Book of the Damned.

I opened it, not at the first page, looking for Cartouche Jonathan Wild, Pranzini, Lacenaire, and read the following passage:

‘The fittest survive.

What is meant by the fittest?

Not the strongest; not the cleverest--

Weakness and stupidity everywhere survive.

There is no way of determining fitness except in that a thing does survive.

“Fitness” then, is only another name for “survival.’”

Finding no Guiteau or Troppmann here, I let the pages slide under my fingers and stopped at this:

‘My own pseudo-conclusion:

That we’ve been damned by giants sound asleep, or by great scientific principles and abstractions that cannot realize themselves: that little harlots have visited their caprices upon us; that clowns, with buckets of water from which they pretend to cast thousands of good-sized fishes have anathemized [sic] us for laughing because, as with all clowns, underlying buffoonery is the desire to be taken seriously; that pale ignorances, presiding over microscopes by which they cannot distinguish flesh from nostoc or fishes’ spawn or frogs’ spawn, have visited upon us their wan solemnities. We’ve been damned by corpses and skeletons and mummies, which twitch and totter with pseudo-life derived from conveniences.’

With some astonishment, I continued to dip into the book, sounding it here and there, but did not bring up even so well-damned a sample of the bottom as Benedict Arnold. Instead I got these:

‘An object from which nets were suspended--

Deflated ballon with its network hanging from it--

A super-dragnet?

That something was trawling overhead?

The birds of Baton Rouge.

I think that we’re fished for. It may be were highly esteemed by super-epicures somewhere.

‘. . . Melancius.

That upon the wings of a super-bat, he broods over this earth and over other worlds, deriving something from them: hovers on wings or wing-like appendages, or planes that are hundreds of miles from tip to tip--a super-evil thing that is exploiting us. By evil I mean that which makes us useful.’

‘. . . British India Company’s steamer Patna, while on a voyage up the Persian Gulf. In May, 1880, on a dark night about 11:30 P.M. there suddenly appeared on each side of the ship an enormous luminous wheel, whirling around, the spokes of which seemed to brush the ship along . . . and although the wheels must have been 500 or 600 yards in diameter, the spokes could be distinctly seen all the way round.’

‘. . . . I shall have to accept that, floating in the sky of this earth, there are often fields of ice as extensive as those on the Arctic Ocean--volumes of water in which are many fishes and frogs--tracts of land covered with caterpillars--’

‘ . . . Black rains--red rains--the fall of a thousand tons of butter.

Jet black snow--pink snow--blue hailstones--hailstones flavored like oranges.

Punk and silk and charcoal.’

‘ . . . A race of tiny beings.

They crucified cockroaches.

Exquisite beings—’

(This description undermines Moskowitz’s claim that Tarkington picked up The Book of the Damned thinking it was a murder mystery.)

Tarkington was a professional humorist, and he could see Fort was very funny; he was also interested in art—and he could see Fort’s artistry, too, finding in him an echo of the Romantic and Weird artists of the nineteenth century:

“But here I turned back to the beginning and read this vigorous and astonishing book straight through, and then re-read it for the pleasure it gave me in the way of its writing and in the substance of what it told. Dorè should have illustrated it, I thought, or Blake. Here indeed was a ‘brush dipped in earthquake and eclipse’; though the wildest mundane earthquakes are but earthquakes in teapots compared to what goes on in the visions conjured up before us by Mr. Charles Fort. For he deals in nightmare, not on the planetary, but on the constellational scale, and the imagination of one who staggers along after him is frequently left gasping and flaccid.”

Tarkington was so moved that he opened a letter about the book to The Bookman—or so it seems. The actual reason for him sending the letter is not quite clear. Most people who have heard of this letter have sourced it to Thayer (who gave an unclear source of it); even Tarkington’s bibliographers had trouble finding the original publication. I did eventually track it down to an August 1920 issue, where it appeared in the back matter, among the advertising, and where Tarkington’s identity was not given but was so badly disguised it might as well have been. All of this background is very confusing, and I am not sure what to make of the letter—other than Tarkington was singing Fort’s praises in a voice similar to the one he would use a few years later:

“A gentleman, writer of fiction by profession, whose name is a ‘household word’ in every home in the land and who lives not far from the most celebrated ‘soldiers’ monument’ in the United States, writes Gossip Shop as follows:

Who in the name of frenzy is Charles Fort? Author of The Book of the Damned. I’m just pulling from influenza and this blamed book kept me all night when I certainly should have slept--and then, in the morning, what is a fevered head to do with assemblies of worlds, some shaped like wheels, some connected by streaming filaments, and one spindle shaped with an axis 100,000 miles long?

A clergyman, old brilliant friend of mine, ‘went insane’ one summer--got over it when his wife got home from Europe but that summer he was gone. I remember when I caught him: he spent all of a hot afternoon telling me, at the University Club, about a secret society of the elect--adepts--who had since days immemorial welcomed (and kept hidden) messages from other planets. That’s where this alleged Charles Fort shows his bulliest dementia--but he’s ‘colossal’--a magnificent nut, with Poe and Blake and Cagliostro and St. John trailing way behind him. And with a gorgeous madman’s humor! What do you know of him? And doesn’t he deserve some BOOKMAN attention? (I never heard of the demoniac cuss.) People must turn to look at his head as he walks down the street; I think it’s a head that would emit noises and explosions, with copper flames playing out from the ears.”

Presumably Tarkington was not aware of Fort because of his distance from Dreiser, who had known of the Bronx philosopher for more than a decade. Also presumably, there was some correspondence between Tarkington and Fort, or at least Tarkington and Fort’s publisher, Boni & Liveright, and Tarkington was pleased enough with Fort’s sense of humor that he agreed to write the preface to Fort’s second book, 1923’s New Lands. The beginning of that preface is quoted above. It then moves on to discuss the book at hand:

Now he has followed ‘The Book of the Damned’ with ‘New Lands’ pointing incidentally to Mars as ‘the San Salvador of the Sky,’ and renewing his passion for the dismayingly significant ‘damned’--tokens and strange hints excluded by the historically mercurial acceptance of ‘Dogmatic Science.’ Of his attack on the astronomers it can at least be said that the literature of indignation is enriched by it.

To the ‘university-trained mind’ here is wildness almost as wild as Roger Bacon’s once appeared to be; though of course even the layest of lay brothers must not assume that all wild science will in time become accepted law, as some of Roger’s did. Retort to Mr. Fort must be left to the outraged astronomer, if indeed any astronomer could feel himself so little outraged as to offer retort. Lay brethren are outside the quarrel and must content themselves with gratitude to a man who writes two such books as ‘New Lands’ and ‘The Book of the Damned’; gratitude for passages and pictures--moving pictures--of such cyclonic activity and dimensions that a whole new area of reader’s imagination stirs in amazement and is brought to life.”

Tarkington, here, is distancing himself, somewhat, from Fort’s most outspoken book, one in which he moved furthest from skepticism and posited his own astronomy. Tarkington was likely skeptical enough of science—what with his acceptance of spiritualism and his disdain for industry and materialism—to nod along with most of what Fort said. Still, it seems that his main reason for liking Fort was the humor—one could read Fort in the same way one could read Tarkington’s own book on collecting published around the same time: both were satires. The introduction further suggests some correspondence between Tarkington and Fort, as Tarkington sees the cinematic qualities of Fort’s writings, and comments upon them—and Fort himself would later tell Maynard Shipley that he thought his books a response to films, which he figured would replace literary fiction. But if there was any correspondence, it has been lost lo these many years.

It was around this time that Tarkington introduced Fort to Alexander Woollcott. The exact sequence of events is unknown—Woollcott mentions it in passing in a later article on Fort and the Fortean Society—and there is no correspondence between the two men at this time. Perhaps Tarkington mentioned Fort to Woollcott in person, one time when traveling through New York; or perhaps Woollcott was attracted to Fort’s second book by noticing Booth Tarkington wrote the foreword and, being a fan of Tarkington, picked up the book and found his way to Fort.

Fort was still on Tarkington’s mind as of June 1930—seven years after Fort’s last book, and despite Tarkington’s blindness. The sourcing here is not as good as I would like—the quotation comes from Thayer, although the citation is corroborated by Tarkington’s bibliographer. It’s from “Booth Tarkington Recalls: That It Is Very Difficult to Be Unorthodox Concerning a Piano,” New York Sun June 19, 1930:

“Few of us nowadays have the wit or the temerity of Mr. Charles Fort. ‘Granted that there will be posterity,’ Mr. Fort says in his book New Lands, ‘we shall have predecessors. Then what is it that is conventionally taught today that will in the future seem as imbecilic as to all present orthodoxies seem the vaporings of preceding systems?

‘Well, for instance, that it is this earth that moves . . .’

Mr. Fort speaks convincingly of the ‘swiftly moving sun,’ and he notices ‘successive appearances in local skies of this earth that indicate this earth is stationary.’

Mr. Fort, however, as the title of his book implies, is less interested in this unmoving earth than in the new lands that move or are rigidly set in the sky. ‘A Balboa of greatness now known only ti himself will stand on a ridge in the sky between two auroral seas.

‘Fountains of Everlasting Challenge.

‘Argosies in parallel lines and rabbles of individual adventurers. Well enough may it be said that there are seeds in the sky. Of such are the germs of colonies.’

Mr. Fort would have the young man of today go not West but Up. ‘He will, or must, go somewhere,’ he says. ‘If directions alone no longer invite him, he may hear invitation in dimensions. . . . Stay and let salvation damn you--or straddle an aurorial beam and paddle it from Rigel to Betelgeuse.’

Any one who is interested in unorthodoxics, who is ‘fair-minded,’ who enjoys having his imagination staggered and his mind dazzled by visions of a future on the constellational scale, should read Mr. Charles Fort’s vigorous and astonishing books: New Lands and The Book of the Damned.”

A year-and-a-half later, Thayer (at J. David Stern’s urging) was organizing the Fortean Society as a way to promote Fort’s third book, written after the return of his own eyesight: Lo! Tarkington was among the earliest of the founders listed—included in press releases before some of the others, such as Alexander Woollcott. Presumably there was some correspondence about this, but it is lost. And he doesn’t seem to have shared any initial thoughts on the matter with Wilson or Woollcott. There is a large gap in the correspondence at this time; Wilson said it was because he was so afraid to learn that Tarkington’s blindness was permanent. In 1937, he told Wilson how his connection to the Society came about (and confirmed that there had been correspondence between him and Fort):

“Years ago some people, no acquaintances of mine and [] this T.T. formed the “Fortean Soc.” and I signed up by mail, as understood the purpose was to be of use to that extraordinary man, Charles Fort, attract notice to his writings by giving a dinner for him, etc. (Fort was a great fellow--disappointed in me because it was a more literary than scientific interest in his works, he wrote me he’d discovered a terrific gulf in some constellation, a trillion mile vacuum, and had named it ‘Tarkington Gulf.’) I never saw [a]live; he used to live with Dreiser.”

Tarkington did allow his name to be used on the Fortean Society propaganda, but he did not appear at the initial meeting, in January 1931. At that time he was recovering from the fifth surgery on his eyes—the successful one. Nor was he particularly impressed with Lo!, which he read in April 1931. He told Wilson it lacked the effervescence of Fort’s earlier two books. If he read Wild Talents, his reaction is unrecorded and his interest in Fort seems as though it would have disappeared, were it not for Thayer and insistence on resuscitating the Society. In 1937, Thayer was in a fight with Fort’s widow and Dreiser over ownership of Fort’s notes, a fight that involved the lawyer Arthur Leonard Ross, who wrote to the founders of the Fortean Society about their understanding of the Society and its intents. Tarkington said that as far as he knew, the Society died with Fort. “I am entirely puzzled by Mr. Thayer’s action in the matter,” he wrote, “and can’t imagine on what ground he stands.”

Thayer, though, did win that fight and started printing the notes in his new magazine devoted to Forteanism. Thayer made certain that the founders all received a copy of the first issue (a letter informing Tarkington of the issue’s publication survives in Tarkington’s papers). The cranky content was a turn-off to Tarkington’s more conservative friends, and after the first issue was sent out he received a letter from one: “Are you honest + truly a founder of the Fortean Society, which seems to include me on its mailing? If so, would you advise me just what the purpose of this organization is--humor, pseudomystification, or a new way of collecting $2 from curious humans. Perhaps the magazine is the house organ of some insane asylum. I give up guessing.” Tarkington’s response to Thayer’s publication was silence—which seems to be significant. In his letter announcing the magazine, Thayer had asked Tarkington for more statements on Fort, but none were ever printed, suggesting Tarkington didn’t bother.

Indeed, his entire strategy seems to have been to ignore Thayer and hope he went away. In a letter to Wilson, he acted to disassociate himself from the whole mater: “Hasten to dispense any suspicions you may have about my friendship for, or with, Mr. Tiffany T. Never see the bird.” After recounting how he came to be attached to the Fortean Society, he continued, Well, this summer Mrs. Fort’s lawyer (Fort’s widow’s) wrote me T.T, withheld all of Fort’s papers--said they belonged to the Fortean Soc. and wouldn’t turn ‘em in--and asked me (the lawyer did) to make a statement that the Soc. was extinct and the widow should have the papers. I did. Heard nothing more until rec’d copy of the 1st number of the mag, which brought me some letters from []. No correspondence with T.T., who seems to be using me pretty freely. He’ll blow up pretty soon, I’d think, Evidently use of the horse [‘s] daughter.” (Tarkington’s handwriting is horrible, and the parentheses represent words I could not decipher.)

Tarkington continued to ignore Thayer, even as Thayer used his name (and his excerpts on Fort) in his magazine and promotion of the Fortean Society. In 1941, with the publication of Fort’s omnibus edition, Thayer wrote Tarkington again, asking him t do something to promote the book—maybe in The Saturday Evening Post. Again, there’s no evidence that Tarkington responded to the letter or wrote up anything on Fort. A few years later, J. David Stern alerted the FBI to Thayer’s effusions, finding them seditious and wanting to be assured that he—and the other founders—would not be associated with Thayer’s actions. He received a memo from the FBI acknowledging that Thayer’s writings tended toward the seditious but, given the erratic publication schedule, there was no more need for investigation. Stern sent a copy of the memorandum to Tarkington and asked that he keep his eyes open lest Thayer use their name sin vain again.

There was some more correspondence between Thayer and Tarkington, but only a small bit of it survives. Apparently in 1943, Thayer wrote Tarkington requesting some kind of favor. That original letter and Tarkington’s response don’t seem to exist, but Thayer’s return letter does. He seems to imply that Tarkington wanted to be separated from the Fortean Society—at least, have no active work in it—which Thayer agreed to. (Tarkington’s name would continue to be used.) Thayer went on to thank Tarkington for remarking upon his sincerity—and there’s the affable Tarkington again, able to smooth over even egregious breaches of etiquette.

Besides the formal use of Tarkington’s name in the Fortean Society magazine and correspondence, and the one issue that reprinted all of Tarkington’s comments on Fort, his name only appeared one other time in the magazine. One assumes that is because Tarkington’s prestige dropped so much that there was little reason for Thayer to call attention to his love of Fort. That other mention was his passing, and that was only the briefest of notices. Thayer did offer an honorary lifetime membership to his wife Susanah, but she declined.