An elusive Fortean from California.

Bertram Taylor Stevens appears in historical records for the Great War. His draft card gives his birth date as 1 August 1890, and the place as Stockton, California. His father was supposed to have come the Golden State from either Illinois or Wisconsin, his mother from Wisconsin. Stevens started working around 1905, when he was fourteen. There’s no particular reason to disbelieve that information, but nor is there corroboration that I can find. I haven’t found a California birth record, or his name in the 1900 or 1910 censuses. Such things happen. It’s just worth noting. At the time he joined the army, Stevens, tall and gray-eyed, captained a dredger in Bay Point, California. Later, he would says that he served fourteen months overseas.

In 1920, he worked as a machinist in Pittsburg, California, not far from Stockton, and was living with a 59 year-old boarder, Robert Wilson. Apparently, Stevens had a short marriage early in the 1920s that ended with his wife’s death. The two had a son, and in 1930 B. T. Stevens, Sr., and Jr. were living in Antioch, California, still in the same general area, on the eastern edge of the Bay Area, near where the Great Central Valley begins. The elder Stevens worked at a paper mill and no longer owned his home—the two rented a house for $25. Within the next five years, the two Stevenses moved to a more rural part of Contra Costa County, where they still lived in 1940, at which time Sr. was working on his own account. He would say, “Now I am no financial wizard and it took much personal sacrifice for me to accumulate the small amount of capital at my command.” He only had an eighth-grade education.

In the months leading up to Pearl Harbor, Stevens sensed war was coming, closed his shop, and went to work at Fulton Shipyards. He seems to have been patriotic, in his way, not declaring for an exemption during the war-to-end-all-words, building ships in preparation for the next, and registering for World War II although he was fifty by its outbreak. He said, “Let us then fight for our America on any front we can and in any way we can. By all means let us remember that it is their—the men and women over-seas—America as much as it is ours, and that they will want it to be the America they left. Not some weird mess of rules, regulations and restrictions, but the America where a person can as someone once said: live each day so that one can look any person in the face and tell him to go to hell. That is my America, and I am sure it is the one the Troops prefer” [Carpenter, A Monthly Journal, March 1944, p. 10].

The sense of fellowship and mutual obligation that underlay his version of patriotism also infected his way of thinking about the economy. In the past, he said in 1945, even as he had been the member of a union, he thought that capital was personal property; but in his old age—now no longer with a union, but still interested in the opinion of union members—he thought of it as something produced by labor: that management didn’t rule, and workers labor, but that they formed a temporary limited liability partnership. Capital, he said, echoing some Marxists, was just the result of past labor. And so, as he contemplated life after war, Stevens thought that he might build a pleasure boat. But he wouldn’t be doing it according to the usual economic rules. Workers “will no longer be just laborers in my mind but partners in production and, therefore, entitled to full knowledge of and a part in the management; plus, and I mean plus, a share in the profits over and above the figured wage upon which the price of the product is figured when and as we can cut the labor costs” [Carpenter, A Monthly Journal, April 1945, p. 37]

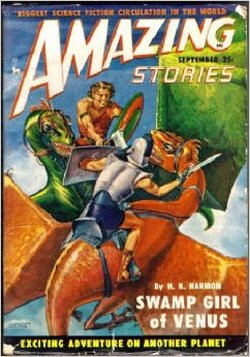

The post-War years also saw Stevens’s thinking turning towards speculative fiction and the occult—or, at least, that is when his name began to appear in publications devoted to such subjects. From his comments, it seems an interest in science fiction, the occult, and alternative sciences for years. In July 1946, he wrote into Ray Palmer’s Amazing Stories to praise the New Age Bible that Palmer was hawking, The Oahspe, in the process displaying a familiarity with Theosophical theories, the Shaver Mystery, occult methods, and the kind of alternative scientific theories that Thayer favored—ones featuring vortexes spinning through the ether:

“Immediately after reading your February issue I sent for a copy of Oahspe and was startled to find therein the statement that such men as I would appear in this age. When you know that five years ago I wrote out a theory of the solar system which nearly parallels the one in Oahspe, though for vortex I used whirlpool, you can understand my amazement. My own theory agrees with Oahspe as to what electricity is and as to what a magnetic field is, though it took me nine years of patient research to arrive at that conclusion.

Millions with a sense that they are alien to this type of civilization and a belief that they have a job to do—do we know or think we know what our individual jobs are? Yes, in my own case and in the case of several others that I know. Amazing, is it not, that in every case we have each trained ourselves for our specific job. Not in orthodox schools, but by actual working at things which gave the most complete training, often dropping

good paying jobs for the chance to begin at the bottom in something else.

In my own case I've spent a lifetime learning about every mechanical device man has built in the last 2,000 years, plus the theoretical basis underlying electrical and atomic physics. Why? Well, one day the opportunity to teach those subjects in a new and practical way will be mine, and I had to be ready. And to that several years experience

in training youngsters in mechanical skills and you have the picture. Why not regular schools? Well, something said a positive no to that, for I would also acquire habit there which I must never let dominate my life, nor might I accept the opinion of any other being as truth until I had proved it.

Nine years ago someone calling himself the "Knower" would, when I'd permit, write through my hands on my typewriter what apparently were sermons to the people of the world telling them//173//how they were mistaken in their attitude toward life and all of it agreeing with Oahspe. Frequently I had the thought that I knew someone some way

in Tibet and received information from there. When the war started, these messages stopped coming. However, imagine if you can my feelings when I read in this issue that there actually were people calling themselves Knowers in Tibet.

Shaver wrote me a letter asking that I disregard the voice and the appearances as they were the product of underground dero. Let me assure you that if I had ever disregarded those voices I'd be dead and forgotten long ago. They have protected my life too many times for me to accept them as dero. When advising against a course of action, it is because of danger to myself or to others. They stress: Do not kill.

Whenever a person, or what looks to be a person, appears here to me, they invariably appear in a circle of pure white light, not strong enough to hurt my eyes, but strong enough to blind most people. My own eyes are fire-tempered by long looking into forging fires and oxy-acetylene flames. I can, and frequently do, look directly at an arc

welder in action when not more than two feet from the arc, often forgetting to pull the hood down when welding myself, which bothers me not at all.

I have sat here in my own home and often seemingly walked and talked with people in

places far from here in space and time. Not alone on this world, but on others too, for often there are things and conditions there that could not be on this earth. Curiously the things I see never astonish me as they seem normal and to me well-known. Why? Because there are things there that I must know and could not know otherwise. Let who will explain it. I haven't any explanation other than that I have a job to do somewhere and some time.”

In 1949, he wrote an essay that appeared in the same magazine. Palmer was still listed as the editor, but he was editing another, Fortean publication, and would only last at Amazing for another year. Stevens’s piece was titled “Inertia is Gravity Plus.” It both forth unorthodox theories of physics in support of some of Shaver’s stories—catnip for Palmer:

“Inertia is the pull of gravity plus that resistance to motion of the medium in which the object moves, that and nothing more. Inertia of rest and of motion are precisely the same thing observed under different aspect, ie. the same thing from different viewpoints.

Any moving object will cease to move when the combined pull of gravity and the resistance to motion of the medium in which the motion is taking place total the exact amount of energy expended un producing the motion.

Since science says that out in space there is nothing, which means no medium to offer resistance, and since they also say that gravity is a negligible factor at best, then by all means let R. Shaver give his ships any speed he desires, it being quite logical to do so.

It being no theory, but fact that a rocket exhaust gains power in a vacuum while resistance to motion vanishes, the speed of a vessel or space craft is theoretically infinite as its maneuverability once it has reached supposedly empty space; the existence of which I for one doubt.

Light speed? How are we to exceed that which does not exist? There being no light as such outside the atmosphere, it followed that so-called light speed is the is the measure of polarization of the atmosphere and has no bearing on possible space speeds at all. Outside of the atmosphere it is as black as the inside of a tar bucket at midnight.

Lorenz-Fitzgerald notwithstanding, there is no contraction in line of flight, this concept being only in the nature of a pup chasing its tail in a welter of mathematical theorems. There is a lengthening of effective length of any object in motion relative to the observer, but decidedly no contraction. In Two Way Stretch at Light Speed [Amazing Stories Jan. 1948], Goble says that the effect on the person entering the vibrating tube would be permanent. If he lived through it, he would be quite normal after escaping from the tube, as would the tube. I have experimented with vibration enough to know this. The sole effect of vibration is relative to the observer and not to the object vibrated providing said object can stand the stresses set up in it by said vibration.

Time being not an effect of speed or of matter, how can speed of matter relative to other matter have any effect on time? Time being only a method of measure in duration, it follows that all motion is relative to an object that the observer considers as not moving or stationary, therefore no true measure of motion or speed is possible, as the object upon which the observer bases his calculations may have various speeds of its own which do not enter into his calculations.

Since science has chosen to measure light motion by time and states that light travels through all mediums at approximately one hundred eighty-six thousand miles per second, how and where does science also reverse itself and say that at precisely that speed time ceases to elapse? That is equivalent to saying that light has no speed relative to time. If time doesn’t exist at light speed neither does light speed exist.”

I have not found any other examples of Stevens’s proposed scientific theories—he seems to have done them chiefly for his own amusement, but his interest in them and his phrasing mean it’s no surprise to learn that his name first appeared in The Fortean Society Magazine in issue 10, summer 1944. “Nor might I accept the opinion of any other being as truth until I had proved it” is the tell—pure Thayer. Even if Stevens had the impulses on his own, the phrasing makes it sound like something out of Doubt. And that is one of the main reasons why I think that the Stevens who lived in Contra Costa County, who was a machinist and mill wright and shipbuilder, was the same Stevens who appeared in the pages of Thayer’s magazine—even as, admittedly, Stevens is a very common name, and Thayer was not always good but including first names, or even first initials. It is also the case that a number of the reports from Stevens came from northern California sources, which would be expected.

Like Kerr, Stevens was an especially active member in the late 1940s; and, like Kerr, he dropped from the pages of the Society’s magazines abruptly. Surprisingly, his occult beliefs are rarely, if ever, implicated in his contributions. For the most part, he stuck to a few mainline topics within the Society. His first contribution, about white blackberries, was paired with one of Kerr’s—about lights in the sky—because both occurred in Mexico, Missouri, and Thayer waggishly wondered if it was a publicity stunt [Fortean Society Magazine 10]. Another of his apparent interests was stray bullets [Doubt 13 and 16]—the first regarding a single bullet, shot from an unattended rifle, that killed two girls, aged 6 and 3. He reported on strange blasts [Doubt 17]. All told, his name appeared in 12 issues between summer 1944 and October 1950. Many of those, though, were unattached to any particular report.

He also had two other interests which suggested a belief that Fortean anomalies challenged science as it was construed, but not the idea of ultimate truth: that a truer, better science was available to those who, as he had, focused on the practical. So he pledged money help the Society republish George F. Gillette’s The Rational Non-Mystical Cosmos, which had also been a fund that Kerr supported [Doubt 20.] Stevens sent in stories that would later be classified as cryptozoology, one of Forteana’s more popular branches: on 5 October 1946 Jennie Dun Levy of Philadelphia found a perfectly formed dog under sink—that was half an inch long; a lion attacked a dog in Iowa [both Doubt 18]. Or something gelatinous washed up on an Oregon beach that was explained away as whale blubber—because only whales grow that large [Doubt 29].

Finally, like so many Forteans—to Thayer’s infinite chagrin—Stevens was a fan of flying saucers—although, what he thought they were, these remain mysteries. His second contribution to Doubt [12] was a story about a light seen above Half Moon Bay, California, around 6:30 p.m. on 18 February 1945, which crashed into nearby Mt. Diablo with a flash of light. University of California scientists had said “a meteor would not be visible at that early hour.” As though that explained anything, Thayer thought. When Thayer succumbed to demands for a second report on flying saucers [Doubt 24], it included clippings from Stevens—those anomalous lights in the sky having become attached to the story of flying saucers. His last contribution [Doubt 30] was also on the topic of flying saucers.

Why did Stevens suddenly lose interest in Fort, the occult, and related subjects? Impossible to say. Maybe he didn’t, and the material just remains undiscovered. Maybe his outlook changed, for some reason. Maybe he was tired of contributing to magazines and wanted to get back to doing things. Maybe his life changed—city directory’s in 1952 and 1955 both have him living with a Helen Stevens. Perhaps he married. Perhaps he worked on that boat after all.

Stevens died 24 June 1973 in Clear Lake, California.

The sense of fellowship and mutual obligation that underlay his version of patriotism also infected his way of thinking about the economy. In the past, he said in 1945, even as he had been the member of a union, he thought that capital was personal property; but in his old age—now no longer with a union, but still interested in the opinion of union members—he thought of it as something produced by labor: that management didn’t rule, and workers labor, but that they formed a temporary limited liability partnership. Capital, he said, echoing some Marxists, was just the result of past labor. And so, as he contemplated life after war, Stevens thought that he might build a pleasure boat. But he wouldn’t be doing it according to the usual economic rules. Workers “will no longer be just laborers in my mind but partners in production and, therefore, entitled to full knowledge of and a part in the management; plus, and I mean plus, a share in the profits over and above the figured wage upon which the price of the product is figured when and as we can cut the labor costs” [Carpenter, A Monthly Journal, April 1945, p. 37]

The post-War years also saw Stevens’s thinking turning towards speculative fiction and the occult—or, at least, that is when his name began to appear in publications devoted to such subjects. From his comments, it seems an interest in science fiction, the occult, and alternative sciences for years. In July 1946, he wrote into Ray Palmer’s Amazing Stories to praise the New Age Bible that Palmer was hawking, The Oahspe, in the process displaying a familiarity with Theosophical theories, the Shaver Mystery, occult methods, and the kind of alternative scientific theories that Thayer favored—ones featuring vortexes spinning through the ether:

“Immediately after reading your February issue I sent for a copy of Oahspe and was startled to find therein the statement that such men as I would appear in this age. When you know that five years ago I wrote out a theory of the solar system which nearly parallels the one in Oahspe, though for vortex I used whirlpool, you can understand my amazement. My own theory agrees with Oahspe as to what electricity is and as to what a magnetic field is, though it took me nine years of patient research to arrive at that conclusion.

Millions with a sense that they are alien to this type of civilization and a belief that they have a job to do—do we know or think we know what our individual jobs are? Yes, in my own case and in the case of several others that I know. Amazing, is it not, that in every case we have each trained ourselves for our specific job. Not in orthodox schools, but by actual working at things which gave the most complete training, often dropping

good paying jobs for the chance to begin at the bottom in something else.

In my own case I've spent a lifetime learning about every mechanical device man has built in the last 2,000 years, plus the theoretical basis underlying electrical and atomic physics. Why? Well, one day the opportunity to teach those subjects in a new and practical way will be mine, and I had to be ready. And to that several years experience

in training youngsters in mechanical skills and you have the picture. Why not regular schools? Well, something said a positive no to that, for I would also acquire habit there which I must never let dominate my life, nor might I accept the opinion of any other being as truth until I had proved it.

Nine years ago someone calling himself the "Knower" would, when I'd permit, write through my hands on my typewriter what apparently were sermons to the people of the world telling them//173//how they were mistaken in their attitude toward life and all of it agreeing with Oahspe. Frequently I had the thought that I knew someone some way

in Tibet and received information from there. When the war started, these messages stopped coming. However, imagine if you can my feelings when I read in this issue that there actually were people calling themselves Knowers in Tibet.

Shaver wrote me a letter asking that I disregard the voice and the appearances as they were the product of underground dero. Let me assure you that if I had ever disregarded those voices I'd be dead and forgotten long ago. They have protected my life too many times for me to accept them as dero. When advising against a course of action, it is because of danger to myself or to others. They stress: Do not kill.

Whenever a person, or what looks to be a person, appears here to me, they invariably appear in a circle of pure white light, not strong enough to hurt my eyes, but strong enough to blind most people. My own eyes are fire-tempered by long looking into forging fires and oxy-acetylene flames. I can, and frequently do, look directly at an arc

welder in action when not more than two feet from the arc, often forgetting to pull the hood down when welding myself, which bothers me not at all.

I have sat here in my own home and often seemingly walked and talked with people in

places far from here in space and time. Not alone on this world, but on others too, for often there are things and conditions there that could not be on this earth. Curiously the things I see never astonish me as they seem normal and to me well-known. Why? Because there are things there that I must know and could not know otherwise. Let who will explain it. I haven't any explanation other than that I have a job to do somewhere and some time.”

In 1949, he wrote an essay that appeared in the same magazine. Palmer was still listed as the editor, but he was editing another, Fortean publication, and would only last at Amazing for another year. Stevens’s piece was titled “Inertia is Gravity Plus.” It both forth unorthodox theories of physics in support of some of Shaver’s stories—catnip for Palmer:

“Inertia is the pull of gravity plus that resistance to motion of the medium in which the object moves, that and nothing more. Inertia of rest and of motion are precisely the same thing observed under different aspect, ie. the same thing from different viewpoints.

Any moving object will cease to move when the combined pull of gravity and the resistance to motion of the medium in which the motion is taking place total the exact amount of energy expended un producing the motion.

Since science says that out in space there is nothing, which means no medium to offer resistance, and since they also say that gravity is a negligible factor at best, then by all means let R. Shaver give his ships any speed he desires, it being quite logical to do so.

It being no theory, but fact that a rocket exhaust gains power in a vacuum while resistance to motion vanishes, the speed of a vessel or space craft is theoretically infinite as its maneuverability once it has reached supposedly empty space; the existence of which I for one doubt.

Light speed? How are we to exceed that which does not exist? There being no light as such outside the atmosphere, it followed that so-called light speed is the is the measure of polarization of the atmosphere and has no bearing on possible space speeds at all. Outside of the atmosphere it is as black as the inside of a tar bucket at midnight.

Lorenz-Fitzgerald notwithstanding, there is no contraction in line of flight, this concept being only in the nature of a pup chasing its tail in a welter of mathematical theorems. There is a lengthening of effective length of any object in motion relative to the observer, but decidedly no contraction. In Two Way Stretch at Light Speed [Amazing Stories Jan. 1948], Goble says that the effect on the person entering the vibrating tube would be permanent. If he lived through it, he would be quite normal after escaping from the tube, as would the tube. I have experimented with vibration enough to know this. The sole effect of vibration is relative to the observer and not to the object vibrated providing said object can stand the stresses set up in it by said vibration.

Time being not an effect of speed or of matter, how can speed of matter relative to other matter have any effect on time? Time being only a method of measure in duration, it follows that all motion is relative to an object that the observer considers as not moving or stationary, therefore no true measure of motion or speed is possible, as the object upon which the observer bases his calculations may have various speeds of its own which do not enter into his calculations.

Since science has chosen to measure light motion by time and states that light travels through all mediums at approximately one hundred eighty-six thousand miles per second, how and where does science also reverse itself and say that at precisely that speed time ceases to elapse? That is equivalent to saying that light has no speed relative to time. If time doesn’t exist at light speed neither does light speed exist.”

I have not found any other examples of Stevens’s proposed scientific theories—he seems to have done them chiefly for his own amusement, but his interest in them and his phrasing mean it’s no surprise to learn that his name first appeared in The Fortean Society Magazine in issue 10, summer 1944. “Nor might I accept the opinion of any other being as truth until I had proved it” is the tell—pure Thayer. Even if Stevens had the impulses on his own, the phrasing makes it sound like something out of Doubt. And that is one of the main reasons why I think that the Stevens who lived in Contra Costa County, who was a machinist and mill wright and shipbuilder, was the same Stevens who appeared in the pages of Thayer’s magazine—even as, admittedly, Stevens is a very common name, and Thayer was not always good but including first names, or even first initials. It is also the case that a number of the reports from Stevens came from northern California sources, which would be expected.

Like Kerr, Stevens was an especially active member in the late 1940s; and, like Kerr, he dropped from the pages of the Society’s magazines abruptly. Surprisingly, his occult beliefs are rarely, if ever, implicated in his contributions. For the most part, he stuck to a few mainline topics within the Society. His first contribution, about white blackberries, was paired with one of Kerr’s—about lights in the sky—because both occurred in Mexico, Missouri, and Thayer waggishly wondered if it was a publicity stunt [Fortean Society Magazine 10]. Another of his apparent interests was stray bullets [Doubt 13 and 16]—the first regarding a single bullet, shot from an unattended rifle, that killed two girls, aged 6 and 3. He reported on strange blasts [Doubt 17]. All told, his name appeared in 12 issues between summer 1944 and October 1950. Many of those, though, were unattached to any particular report.

He also had two other interests which suggested a belief that Fortean anomalies challenged science as it was construed, but not the idea of ultimate truth: that a truer, better science was available to those who, as he had, focused on the practical. So he pledged money help the Society republish George F. Gillette’s The Rational Non-Mystical Cosmos, which had also been a fund that Kerr supported [Doubt 20.] Stevens sent in stories that would later be classified as cryptozoology, one of Forteana’s more popular branches: on 5 October 1946 Jennie Dun Levy of Philadelphia found a perfectly formed dog under sink—that was half an inch long; a lion attacked a dog in Iowa [both Doubt 18]. Or something gelatinous washed up on an Oregon beach that was explained away as whale blubber—because only whales grow that large [Doubt 29].

Finally, like so many Forteans—to Thayer’s infinite chagrin—Stevens was a fan of flying saucers—although, what he thought they were, these remain mysteries. His second contribution to Doubt [12] was a story about a light seen above Half Moon Bay, California, around 6:30 p.m. on 18 February 1945, which crashed into nearby Mt. Diablo with a flash of light. University of California scientists had said “a meteor would not be visible at that early hour.” As though that explained anything, Thayer thought. When Thayer succumbed to demands for a second report on flying saucers [Doubt 24], it included clippings from Stevens—those anomalous lights in the sky having become attached to the story of flying saucers. His last contribution [Doubt 30] was also on the topic of flying saucers.

Why did Stevens suddenly lose interest in Fort, the occult, and related subjects? Impossible to say. Maybe he didn’t, and the material just remains undiscovered. Maybe his outlook changed, for some reason. Maybe he was tired of contributing to magazines and wanted to get back to doing things. Maybe his life changed—city directory’s in 1952 and 1955 both have him living with a Helen Stevens. Perhaps he married. Perhaps he worked on that boat after all.

Stevens died 24 June 1973 in Clear Lake, California.