A mysterious, nearly anonymous, but consistent Fortean.

As a general rule, I don’t write up Forteans I cannot find any information on. I went through all issues of Doubt—except 22—and noted everyone mentioned as a Fortean. That gave me close to five hundred names. Some of those I have been able to run down—and then write up. More than a few I have nothing more than a name, and sometimes just a pseudonym. Usually, it’s only a surname, occasionally with a first initial. As in the case here.

I do have some information on this Fortean. She was a woman. She lived in or near Buffalo, NY. (Perhaps she knew H. W. Giles.) And her last name was Goldstein. Not a lot to go on—not enough, as it turns out. There are too many possible people by that name in the Buffalo area. Even if I narrow the search with her (possible) first initial, B. Making the search even more difficult, it it possible that there was another Goldstein in the Fortean Society, one who lived in Los Angeles. Thayer’s use of the first initial was haphazard, and so it is not always clear to which Goldstein he referred.

But she’s still worth writing up, simply because she was a consistent Fortean, one who started in the mid-1940s but continued on to the bitter end, her last contribution a poem in the final issue of Doubt. Thayer called her “our good member” (Doubt 61) and said her “high standard of data is wonderfully consistent, year in, year out” (Doubt 24).

Goldstein’s name first appeared in Doubt 11—first issue by that name—one of many referring to the mysterious light that had shot over the Midwest and attracted so much Fortean attention. That was the winter of 1944. She was back in the following issue, with another tale of sky-lights, this one streaking across Philadelphia then bursting with sufficient force to open doors. It was reported in the papers on 4 May 1945. As with so many other Forteans, she was fascinated by such atmospheric anomalies, and followed them as they were transformed into flying saucers. Her third contribution, Doubt 17, winter 1946, was about weird lights over Italy that could make sharp turns. Her name was listed among those who contributed to Thayer’s UFO digests [Doubt 19, Doubt 30].

Her Fortean enthusiasms, though, extended beyond mysterious lights in the sky. She contributed clippings about stray bullets [Doubt 17, 260], 35 New Zealand lambs killed with knife-precision in a single night [Doubt 18, 274], a strange hum in Britain [Doubt 31, 52], the discovery of a new species of snake on an Australian island that was recently created by a flood [Doubt 32, 71], poltergeist activities in a Finnish house [Doubt 24, 364], and the falling of a four-foot sturgeon from the sky that was blamed on an eagle [Doubt 50, 368]. She had a sense of whimsy, sending in a story about a red fox that wandered into a Chicago bar [Doubt 20, 303] and another about a psychiatrist who recommended that dogs in Manhattan go to the store and pick out their own toys because apartment-life was stressful on canines [Doubt 49, 355]. There were, in addition, many, many credits that were unconnected to specific reports. One credit stands out as odd: an eyewitness report of earthquakes and storms in Los Angeles. Maybe that meant Goldstein traveled. Maybe there was more than one Goldstein.

The main Goldstein also shared Thayer’s sense of outrage at world developments. He bestowed his greatest praise upon her for a story she sent in about an American plane bombing an American submarine. The defense department claimed not to have heard to he incident; other people suggested pilot error—the pilot did not recognize the code the submarine captain provided. Thayer wanted to know why American planes were bombing anyone. It was 1949 [Doubt 24, 362.] And she suggested that Fortean anomalies might be the work of Karma: “Our good member B. Goldstein asks, of ‘accidents’ to hunters, ‘Does the aura of murderous intent attract something that boomerangs--and pursues them?’ ANS: I doubt it, but it’s a wonderful suggestion to transmit to the gods of things as they ought to be. We have a few instances of the hunted turning on their would-be killers, or related phenoms” [Doubt 49, 352].

She transformed some of this anger into a poem. Like Thayer, she was disturbed by the way that the developmental of science and increasing size of the government would increasingly be a burden on American taxpayers. She sent in a large pile of clippings on the point, and then summarized:

“These figures astronomical

Make me QUITE gastronomical-

ly ILL.

Like U.F.O.s They climb the sky

To soar vertiginously high.

Who’ll pay the bill???

WHY

You--

and I--

WE Will!!!!” [Doubt 61, 70.]

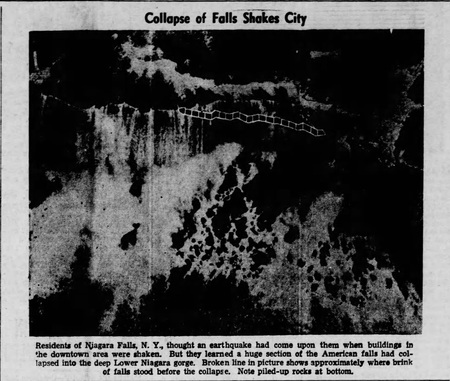

Most worth noting, though, are her critical reading skills. One way to think of Forteans, especially those in Thayer’s mould, is not as interested in the anomalies at all—but in the deficits of journalism. Journalists just could not get the stories straight, could not see the hidden assumptions, could not express themselves. And out of these mistakes, conspiracies could be spun—Thayer was more than happy to do that, too, but often he was just as interested in the plain incompetence of the press. Living in Buffalo, Goldstein-whomever she was—got a front-row seat to one of these confusing stories. In September 1946 came reports that at Niagara Falls tens of tons of rocks had fallen. What had caused it? Were the Falls disfigured? Impossible to tell from the news reports [Doubt 17, 258].

Francis A. Seyfried, an official with the park, was quoted both saying that the Falls had ben noticeably changed, and that there had been no effect on the landscape. Similarly, no one was sure what had happened: did an earthquake cause the rock fall—or did a rock slide shake the ground so much as to feel like an earthquake? Had rocks even fallen? Goldstein gave Thayer plenty of grist for his journalism-grinding mill. But it was another Fortean, Henry Hoernlein, who provided the best ingredient. He sent in an article that explained,“a natural motion of the earth was responsible for the disturbance.” Of course! That was not an explanation, but more journalistic mumbling. Either a rock slide or an earthquake could be characterized as a natural motion of the earth. That the journalist did not see the obvious gap in his logic was a sign of poor thinking. But it also gave Thayer, and other Forteans, material for their more conspiratorial thinking. Why specify that the disturbance was caused by a “natural motion” of the earth? Were their unnatural motions? Were their natural motions that were not being considered—beyond a rock slide and earthquake?

Goldstein also pointed out similar lapses in one Fortean. Thayer had previously praised R. L. Farnsworth, president of the Rocket Society for mentioning Fort to the press. But Farnsworth’s plans were also colonialist: he wanted America to create a space empire. That’s when Thayer changed his opinion, and attacked Farnsworth. Goldstein had come to similar conclusions about Farnsworth independently—it’s not clear if she knew he was a Fortean or not. She clipped a story about him and his galactic ambitions and notated it: “Did it ever occur to Mr. F., that someone else may be there already?”

Unacknowledged assumptions, they were the seed for imagining whole new worlds.

As a general rule, I don’t write up Forteans I cannot find any information on. I went through all issues of Doubt—except 22—and noted everyone mentioned as a Fortean. That gave me close to five hundred names. Some of those I have been able to run down—and then write up. More than a few I have nothing more than a name, and sometimes just a pseudonym. Usually, it’s only a surname, occasionally with a first initial. As in the case here.

I do have some information on this Fortean. She was a woman. She lived in or near Buffalo, NY. (Perhaps she knew H. W. Giles.) And her last name was Goldstein. Not a lot to go on—not enough, as it turns out. There are too many possible people by that name in the Buffalo area. Even if I narrow the search with her (possible) first initial, B. Making the search even more difficult, it it possible that there was another Goldstein in the Fortean Society, one who lived in Los Angeles. Thayer’s use of the first initial was haphazard, and so it is not always clear to which Goldstein he referred.

But she’s still worth writing up, simply because she was a consistent Fortean, one who started in the mid-1940s but continued on to the bitter end, her last contribution a poem in the final issue of Doubt. Thayer called her “our good member” (Doubt 61) and said her “high standard of data is wonderfully consistent, year in, year out” (Doubt 24).

Goldstein’s name first appeared in Doubt 11—first issue by that name—one of many referring to the mysterious light that had shot over the Midwest and attracted so much Fortean attention. That was the winter of 1944. She was back in the following issue, with another tale of sky-lights, this one streaking across Philadelphia then bursting with sufficient force to open doors. It was reported in the papers on 4 May 1945. As with so many other Forteans, she was fascinated by such atmospheric anomalies, and followed them as they were transformed into flying saucers. Her third contribution, Doubt 17, winter 1946, was about weird lights over Italy that could make sharp turns. Her name was listed among those who contributed to Thayer’s UFO digests [Doubt 19, Doubt 30].

Her Fortean enthusiasms, though, extended beyond mysterious lights in the sky. She contributed clippings about stray bullets [Doubt 17, 260], 35 New Zealand lambs killed with knife-precision in a single night [Doubt 18, 274], a strange hum in Britain [Doubt 31, 52], the discovery of a new species of snake on an Australian island that was recently created by a flood [Doubt 32, 71], poltergeist activities in a Finnish house [Doubt 24, 364], and the falling of a four-foot sturgeon from the sky that was blamed on an eagle [Doubt 50, 368]. She had a sense of whimsy, sending in a story about a red fox that wandered into a Chicago bar [Doubt 20, 303] and another about a psychiatrist who recommended that dogs in Manhattan go to the store and pick out their own toys because apartment-life was stressful on canines [Doubt 49, 355]. There were, in addition, many, many credits that were unconnected to specific reports. One credit stands out as odd: an eyewitness report of earthquakes and storms in Los Angeles. Maybe that meant Goldstein traveled. Maybe there was more than one Goldstein.

The main Goldstein also shared Thayer’s sense of outrage at world developments. He bestowed his greatest praise upon her for a story she sent in about an American plane bombing an American submarine. The defense department claimed not to have heard to he incident; other people suggested pilot error—the pilot did not recognize the code the submarine captain provided. Thayer wanted to know why American planes were bombing anyone. It was 1949 [Doubt 24, 362.] And she suggested that Fortean anomalies might be the work of Karma: “Our good member B. Goldstein asks, of ‘accidents’ to hunters, ‘Does the aura of murderous intent attract something that boomerangs--and pursues them?’ ANS: I doubt it, but it’s a wonderful suggestion to transmit to the gods of things as they ought to be. We have a few instances of the hunted turning on their would-be killers, or related phenoms” [Doubt 49, 352].

She transformed some of this anger into a poem. Like Thayer, she was disturbed by the way that the developmental of science and increasing size of the government would increasingly be a burden on American taxpayers. She sent in a large pile of clippings on the point, and then summarized:

“These figures astronomical

Make me QUITE gastronomical-

ly ILL.

Like U.F.O.s They climb the sky

To soar vertiginously high.

Who’ll pay the bill???

WHY

You--

and I--

WE Will!!!!” [Doubt 61, 70.]

Most worth noting, though, are her critical reading skills. One way to think of Forteans, especially those in Thayer’s mould, is not as interested in the anomalies at all—but in the deficits of journalism. Journalists just could not get the stories straight, could not see the hidden assumptions, could not express themselves. And out of these mistakes, conspiracies could be spun—Thayer was more than happy to do that, too, but often he was just as interested in the plain incompetence of the press. Living in Buffalo, Goldstein-whomever she was—got a front-row seat to one of these confusing stories. In September 1946 came reports that at Niagara Falls tens of tons of rocks had fallen. What had caused it? Were the Falls disfigured? Impossible to tell from the news reports [Doubt 17, 258].

Francis A. Seyfried, an official with the park, was quoted both saying that the Falls had ben noticeably changed, and that there had been no effect on the landscape. Similarly, no one was sure what had happened: did an earthquake cause the rock fall—or did a rock slide shake the ground so much as to feel like an earthquake? Had rocks even fallen? Goldstein gave Thayer plenty of grist for his journalism-grinding mill. But it was another Fortean, Henry Hoernlein, who provided the best ingredient. He sent in an article that explained,“a natural motion of the earth was responsible for the disturbance.” Of course! That was not an explanation, but more journalistic mumbling. Either a rock slide or an earthquake could be characterized as a natural motion of the earth. That the journalist did not see the obvious gap in his logic was a sign of poor thinking. But it also gave Thayer, and other Forteans, material for their more conspiratorial thinking. Why specify that the disturbance was caused by a “natural motion” of the earth? Were their unnatural motions? Were their natural motions that were not being considered—beyond a rock slide and earthquake?

Goldstein also pointed out similar lapses in one Fortean. Thayer had previously praised R. L. Farnsworth, president of the Rocket Society for mentioning Fort to the press. But Farnsworth’s plans were also colonialist: he wanted America to create a space empire. That’s when Thayer changed his opinion, and attacked Farnsworth. Goldstein had come to similar conclusions about Farnsworth independently—it’s not clear if she knew he was a Fortean or not. She clipped a story about him and his galactic ambitions and notated it: “Did it ever occur to Mr. F., that someone else may be there already?”

Unacknowledged assumptions, they were the seed for imagining whole new worlds.