He cashed in on Forteana, and his writings were influenced by Fort—even as he often bristled at other Forteans.

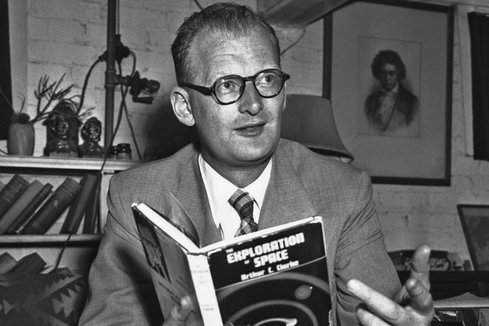

Arthur C. Clarke is too well known, too written about to warrant anything more than a thumbnail sketch here. Indeed, Bob Rickards wrote about his Forteanism in the January 2015 Fortean Times.

Born 16 December 1917 in Somerset, England, he had an early interest in astronomy and science fiction, eventually becoming one of the early participants of British fandom and a teenage member of the British Interplanetary Society. He served in the RAF during World War II, working on radar, and afterwards graduated from King’s College in London. Clarke did legitimate scientific work—contributing to the idea of geostationary satellites—but made his name as a scientific writer. He was known for being boisterous and opinionated, picking fights and quickly forgetting about them, too.

Arthur C. Clarke is too well known, too written about to warrant anything more than a thumbnail sketch here. Indeed, Bob Rickards wrote about his Forteanism in the January 2015 Fortean Times.

Born 16 December 1917 in Somerset, England, he had an early interest in astronomy and science fiction, eventually becoming one of the early participants of British fandom and a teenage member of the British Interplanetary Society. He served in the RAF during World War II, working on radar, and afterwards graduated from King’s College in London. Clarke did legitimate scientific work—contributing to the idea of geostationary satellites—but made his name as a scientific writer. He was known for being boisterous and opinionated, picking fights and quickly forgetting about them, too.

Clarke traveled extensively. In 1956, he moved to Sri Lanka, which became home for the rest of his life. Clarke enjoyed the sea—after a trip to Florida, he told Eric Frank Russell he’d become part fish—and was part of the Underwater Explorers Club. He did some salvage work. In the 1980s, Clarke produced a number of television shows on topics that were, broadly considered, Fortean; accompanying books were published. He was knighted in 2000.

Arthur Charles Clarke died 19 March 2008, aged 90.

*******

Almost certainly, Clarke’s exposure to Fort came through the 1934 serialization of “Lo!” in the pulp magazine “Astounding Science Fiction.” He would have been 17 at the time, and was a reader of that magazine, although getting it in Britain was a little more complicated than its home country. Many, many years later—in a 1989 book to be exact, Astounding Days, which had him writing about Astounding’s run—he wrote, in part:

“It might be argued that a magazine claiming to publish fiction has not right to fob off factual articles on its readers. Whether _Ranch Romances_, _Western Love Stories_, _et al_ ever printed thoughtful essays on land-ownership, cattle-branding, Indian sign language and similar relevant subjects, I have no idea; but somehow I doubt it.

Apart from the occasional ‘fillers,’ a few of which we have already discussed, the Clayton _Astounding_ never published any non-fiction. The new management waited six months, then announced that it would start serializing Charles Fort’s _Lo!_ in the April 1934 issue. It was to run for eight installments, concluding in November.

No choice could have been more appropriate for a science fiction magazine, and Fort’s writing was to have an immense influence on the field.”

Clarke’s subsequent careers in science fiction and rocketry-lobbying would only have reinforced this early acquaintance with Fort. Eric Frank Russell was one of Fort’s early mentors in science fiction writing; the pulps constantly referred to Fort; and even the British Interplanetary Society had some Fortean connections. Meetings of British science fiction fans at the White Horse Pub almost certainly put Fort on the agenda, occasionally, given the number of Forteans in its ranks. “I found his eccentric—even explosive—style stimulating and indeed mind-expanding,” Clarke wrote in 1989. Clarke, though, never became a member of the Fortean Society, though Russell was its British representative.

There’s no doubt that Fortean ideas and even Fortean practices worked their way into Clarke’s life. In June 1949, he sent a clipping to Russell. Russell must have sent a letter of appreciation, because in October, Clarke replied, “Glad the cutting was useful. I keep an eye open for anything out of the way. My coverage of journals in physics, astronomy etc. being virtually complete. [All languages + countries either side of the Iron Curtain—not that I can read ‘em, but I’ve got 100 or so abstractors on my books who can.]” At the time, Clarke worked for the journal Physics Abstracts. Clarke continued to think of Russell as deserving clippings—in the mid-1960s he sent him the transcript of a story about luminous objects in the German sky.

It seems likely that Russell passed on the clipping to Thayer, for appearance in Doubt, and maybe another clipping, too, something that was sent with a no-longer-extant letter. For there are two references in the magazine which likely refer to Arthur C. Clarke. The first appeared in Doubt 27, from the winter of 1949, and was associated with a fall of fishes reported by an Indian newspaper. It is credited to “non-member Clarke.” The second came two issues later, in July 1950. Thayer reported a supposed explosion on the surface of Mars noticed by a Japanese man. There was a long list of contributors to the story, and among them was, again, Clarke, though this time there was no caveat about membership status. Of course it is possible that there was someone else with the surname Clarke who sent in these items, and may even have become a member.

It doesn’t take too much to see Fortean themes in some of Clarke’s fiction—though he was incredibly prolific and I make no pretense of having surveyed his entire oeuvre. “A Walk in the Dark,” for example, appeared in Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1950. (That magazine, by the way, was edited by Sam Merwin, who had strong Fortean inclinations.) As author Scott Nicolay pointed out, the story has a subtle reference to Fortean Ivan Sanderson, and is a story about (maybe) unknown creatures. Bob Rickard notes that his 1953 “Childhood’s End” plays with both the idea that humans are the property of aliens and also psychic powers that likely derive from his connection to fellow Fortean Harold Chibbett (another friend of Russell’s) and his reading of Fort’s “Wild Talents” (as well as science fiction editor John W. Campbell’s then-current fascination with psychic phenomena). Wild Talents, of a sort, also appear in his 1962 “Dog Star.”

Clarke’s most famous work of fiction, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” is also deeply Fortean. Based on his much earlier story “Sentinel” (aka “Sentinel of Eternity”) the underlying premise is that aliens have been involved with human evolution from the very beginning, guiding it: we re property, in other words. As well, Clarke’s most famous phrase is also deeply Fortean. In 1973, he wrote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Fort had written, in “Wild Talents”: “I was a witness of a performance that may some day be considered understandable, but that, in these primitive times, so transcends what is said to be the known that it is what I mean by magic.” And: “I conceive of two magics: one as representing unknown law, and the other as expressing lawlessness—or that a man may fall from a roof, and alight unharmed, because of anti-gravitational law; and that another man may fall from a roof, and alight unharmed, as an expression of the exceptional, of the defiance of gravitation, of universal inconsistency, of defiance of everything.”

In the 1980s, Clarke was associated with the production of three documentary series, and their associated books: Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World_ (1980); _Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers_ (1984); and _Arthur C. Clarke’s Chronicles of the Strange and Mysterious_ (1987). In his 1989 essay on Fort, Clarke noted, “Years later he undoubtedly helped to inspire (if that’s the right word) my . . . Yorkshire Television productions.” These books dealt with various paranormal phenomena, and while being generally open-minded, Clarke did not think that there were yet-undiscovered psychic powers. Whatever hope he may have had as a younger man no longer held, after forty years of failure. “If there really was something in telepathy, ESP, etc, it would have been proven by now without doubt,” Rickard quotes him as saying.

He also seems to have been somewhat disenchanted by Forteanism—though it is not clear, from the available evidence, if that was a change over time, or a reservation he nursed all along. Likely one cause of the disenchantment, if indeed it developed over time, was Robert L. Farnsworth, a Fortean who wanted America to colonize the moon and claim it for itself. Clarke was very disturbed by such an attitude—he thought nationalism was at the back of the (then-recent) horrors of World War II, and wanted space exploration to avoid such narrow-thinking. The British Interplanetary Society also went after Farnsworth separately.

Also figuring into his disapproval of Forteanism was evidence that the kind of reports Fort used were often wrong. He wrote in 1989, “Yet many of the news items dug up by Fort in his decades of research seem to be quite inexplicable—_if_ they are true. That, of course, is the problem; hoaxes, stories manufactured by unscrupulous journalists trying to make a scoop, hallucinations, honest misinterpretations—these must explain a many of Fort’s anomalies. As he freely admitted, ‘I shall be excused of having assembled lies, yarns, hoaxes and superstitions. To some degree I think so, myself. To some degree I do not. I offer the data.’”

An example of such wrongness came to him in 1954. He wrote to Russell, “Dear Yerrik, “I don’t believe in mysterious footprints, after a little episode that happened to me in Florida. Seems that occasionally the tracks of an enormous bird are observed on one of the beaches there, and the naturalists come running down from the north with field-glasses and cameras. The whole baffling business has doubtless been written up somewhere in the Fortean magazine.

“Well, I was taken into a back room and shown the footprints, neatly built round a pair of boots. Whenever the character who owns them feels like a bit of fun, he puts them on and walks _backwards_ down into the sea. Then he sends a wire to his ornithologist friends, ‘Come at once—it’s back!’ So everyone is happy. . . .”

The ellipse appears in the original, but not noted is that, indeed, Ivan Sanderson had investigated such footprints, and written about them for Fate in 1948 (and the story had been picked up by Doubt, as Clarke rightly supposed). Sanderson had speculated that the tracks had been left by giant penguins, the truth of the matter only coming out some four decades later, when the hoaxers publicly confessed. It was this kind of undermining of Forteana that propped Clarke’s cynicism of Forteans. As he wrote in that 1989 piece, “I considered them (and still do) to be ignorant and opinionated science-bashers.” He had little use for the founders of the Fortean Society, whom he considered “intellectuals,” with that word meaning “someone educated beyond his intelligence.”

That dim view came through in one of the stories that Clarke set in the White Horse Pub (which he renamed, for fictional purposes, The White Hart). In 1956, he published “What Goes Up.” Andrew May sees it as an attack on pseudoscientists, especially those of a Fortean stripe: a supplicant of the UFO “religion” visits the White Hart to meet science fiction aficionados, whom he assumes will be believers in flying saucers as well. They string him along with wild tales of an antigravity device, but he cannot recognize the implausibilities and so writes it up for his own publication as new information.

By the 1960s, Clarke thought Forteanism itself was some kind of prank. In a postscript to a 1967 letter to Russell, he said, “I’m writing an article to prove that Charles Fort never existed but was invented as a practical joke—haven’t decided by whom.” His 1989 essay concluded, “Despite [Fort’s] avowed scepticism, he continually promotes the theory—totally absurd in the 1930s, or even in the 1830s—that the stars and planets are really quite close, and the earth is surrounded by some kind of shell from which material occasionally falls, If Fort had lived to see men walk on the moon (well, he would have been only 95 . . .) he would have had to eat a good many of his sarcastic words about astronomers. Scepticism is one thing; stupidity is another. But then, everyone is stupid about _something_.”

Ultimately, I think that Rickard’s assessment of Clarke was spot-on. He was interested in the facts that Fort accumulated, the various stories, and thought that there might be some scientific law to explain them—in the manner of Maynard Shipley and John W. Campbell. He was otherwise opposed to Fort’s more subversive elements.

Arthur Charles Clarke died 19 March 2008, aged 90.

*******

Almost certainly, Clarke’s exposure to Fort came through the 1934 serialization of “Lo!” in the pulp magazine “Astounding Science Fiction.” He would have been 17 at the time, and was a reader of that magazine, although getting it in Britain was a little more complicated than its home country. Many, many years later—in a 1989 book to be exact, Astounding Days, which had him writing about Astounding’s run—he wrote, in part:

“It might be argued that a magazine claiming to publish fiction has not right to fob off factual articles on its readers. Whether _Ranch Romances_, _Western Love Stories_, _et al_ ever printed thoughtful essays on land-ownership, cattle-branding, Indian sign language and similar relevant subjects, I have no idea; but somehow I doubt it.

Apart from the occasional ‘fillers,’ a few of which we have already discussed, the Clayton _Astounding_ never published any non-fiction. The new management waited six months, then announced that it would start serializing Charles Fort’s _Lo!_ in the April 1934 issue. It was to run for eight installments, concluding in November.

No choice could have been more appropriate for a science fiction magazine, and Fort’s writing was to have an immense influence on the field.”

Clarke’s subsequent careers in science fiction and rocketry-lobbying would only have reinforced this early acquaintance with Fort. Eric Frank Russell was one of Fort’s early mentors in science fiction writing; the pulps constantly referred to Fort; and even the British Interplanetary Society had some Fortean connections. Meetings of British science fiction fans at the White Horse Pub almost certainly put Fort on the agenda, occasionally, given the number of Forteans in its ranks. “I found his eccentric—even explosive—style stimulating and indeed mind-expanding,” Clarke wrote in 1989. Clarke, though, never became a member of the Fortean Society, though Russell was its British representative.

There’s no doubt that Fortean ideas and even Fortean practices worked their way into Clarke’s life. In June 1949, he sent a clipping to Russell. Russell must have sent a letter of appreciation, because in October, Clarke replied, “Glad the cutting was useful. I keep an eye open for anything out of the way. My coverage of journals in physics, astronomy etc. being virtually complete. [All languages + countries either side of the Iron Curtain—not that I can read ‘em, but I’ve got 100 or so abstractors on my books who can.]” At the time, Clarke worked for the journal Physics Abstracts. Clarke continued to think of Russell as deserving clippings—in the mid-1960s he sent him the transcript of a story about luminous objects in the German sky.

It seems likely that Russell passed on the clipping to Thayer, for appearance in Doubt, and maybe another clipping, too, something that was sent with a no-longer-extant letter. For there are two references in the magazine which likely refer to Arthur C. Clarke. The first appeared in Doubt 27, from the winter of 1949, and was associated with a fall of fishes reported by an Indian newspaper. It is credited to “non-member Clarke.” The second came two issues later, in July 1950. Thayer reported a supposed explosion on the surface of Mars noticed by a Japanese man. There was a long list of contributors to the story, and among them was, again, Clarke, though this time there was no caveat about membership status. Of course it is possible that there was someone else with the surname Clarke who sent in these items, and may even have become a member.

It doesn’t take too much to see Fortean themes in some of Clarke’s fiction—though he was incredibly prolific and I make no pretense of having surveyed his entire oeuvre. “A Walk in the Dark,” for example, appeared in Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1950. (That magazine, by the way, was edited by Sam Merwin, who had strong Fortean inclinations.) As author Scott Nicolay pointed out, the story has a subtle reference to Fortean Ivan Sanderson, and is a story about (maybe) unknown creatures. Bob Rickard notes that his 1953 “Childhood’s End” plays with both the idea that humans are the property of aliens and also psychic powers that likely derive from his connection to fellow Fortean Harold Chibbett (another friend of Russell’s) and his reading of Fort’s “Wild Talents” (as well as science fiction editor John W. Campbell’s then-current fascination with psychic phenomena). Wild Talents, of a sort, also appear in his 1962 “Dog Star.”

Clarke’s most famous work of fiction, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” is also deeply Fortean. Based on his much earlier story “Sentinel” (aka “Sentinel of Eternity”) the underlying premise is that aliens have been involved with human evolution from the very beginning, guiding it: we re property, in other words. As well, Clarke’s most famous phrase is also deeply Fortean. In 1973, he wrote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Fort had written, in “Wild Talents”: “I was a witness of a performance that may some day be considered understandable, but that, in these primitive times, so transcends what is said to be the known that it is what I mean by magic.” And: “I conceive of two magics: one as representing unknown law, and the other as expressing lawlessness—or that a man may fall from a roof, and alight unharmed, because of anti-gravitational law; and that another man may fall from a roof, and alight unharmed, as an expression of the exceptional, of the defiance of gravitation, of universal inconsistency, of defiance of everything.”

In the 1980s, Clarke was associated with the production of three documentary series, and their associated books: Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World_ (1980); _Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers_ (1984); and _Arthur C. Clarke’s Chronicles of the Strange and Mysterious_ (1987). In his 1989 essay on Fort, Clarke noted, “Years later he undoubtedly helped to inspire (if that’s the right word) my . . . Yorkshire Television productions.” These books dealt with various paranormal phenomena, and while being generally open-minded, Clarke did not think that there were yet-undiscovered psychic powers. Whatever hope he may have had as a younger man no longer held, after forty years of failure. “If there really was something in telepathy, ESP, etc, it would have been proven by now without doubt,” Rickard quotes him as saying.

He also seems to have been somewhat disenchanted by Forteanism—though it is not clear, from the available evidence, if that was a change over time, or a reservation he nursed all along. Likely one cause of the disenchantment, if indeed it developed over time, was Robert L. Farnsworth, a Fortean who wanted America to colonize the moon and claim it for itself. Clarke was very disturbed by such an attitude—he thought nationalism was at the back of the (then-recent) horrors of World War II, and wanted space exploration to avoid such narrow-thinking. The British Interplanetary Society also went after Farnsworth separately.

Also figuring into his disapproval of Forteanism was evidence that the kind of reports Fort used were often wrong. He wrote in 1989, “Yet many of the news items dug up by Fort in his decades of research seem to be quite inexplicable—_if_ they are true. That, of course, is the problem; hoaxes, stories manufactured by unscrupulous journalists trying to make a scoop, hallucinations, honest misinterpretations—these must explain a many of Fort’s anomalies. As he freely admitted, ‘I shall be excused of having assembled lies, yarns, hoaxes and superstitions. To some degree I think so, myself. To some degree I do not. I offer the data.’”

An example of such wrongness came to him in 1954. He wrote to Russell, “Dear Yerrik, “I don’t believe in mysterious footprints, after a little episode that happened to me in Florida. Seems that occasionally the tracks of an enormous bird are observed on one of the beaches there, and the naturalists come running down from the north with field-glasses and cameras. The whole baffling business has doubtless been written up somewhere in the Fortean magazine.

“Well, I was taken into a back room and shown the footprints, neatly built round a pair of boots. Whenever the character who owns them feels like a bit of fun, he puts them on and walks _backwards_ down into the sea. Then he sends a wire to his ornithologist friends, ‘Come at once—it’s back!’ So everyone is happy. . . .”

The ellipse appears in the original, but not noted is that, indeed, Ivan Sanderson had investigated such footprints, and written about them for Fate in 1948 (and the story had been picked up by Doubt, as Clarke rightly supposed). Sanderson had speculated that the tracks had been left by giant penguins, the truth of the matter only coming out some four decades later, when the hoaxers publicly confessed. It was this kind of undermining of Forteana that propped Clarke’s cynicism of Forteans. As he wrote in that 1989 piece, “I considered them (and still do) to be ignorant and opinionated science-bashers.” He had little use for the founders of the Fortean Society, whom he considered “intellectuals,” with that word meaning “someone educated beyond his intelligence.”

That dim view came through in one of the stories that Clarke set in the White Horse Pub (which he renamed, for fictional purposes, The White Hart). In 1956, he published “What Goes Up.” Andrew May sees it as an attack on pseudoscientists, especially those of a Fortean stripe: a supplicant of the UFO “religion” visits the White Hart to meet science fiction aficionados, whom he assumes will be believers in flying saucers as well. They string him along with wild tales of an antigravity device, but he cannot recognize the implausibilities and so writes it up for his own publication as new information.

By the 1960s, Clarke thought Forteanism itself was some kind of prank. In a postscript to a 1967 letter to Russell, he said, “I’m writing an article to prove that Charles Fort never existed but was invented as a practical joke—haven’t decided by whom.” His 1989 essay concluded, “Despite [Fort’s] avowed scepticism, he continually promotes the theory—totally absurd in the 1930s, or even in the 1830s—that the stars and planets are really quite close, and the earth is surrounded by some kind of shell from which material occasionally falls, If Fort had lived to see men walk on the moon (well, he would have been only 95 . . .) he would have had to eat a good many of his sarcastic words about astronomers. Scepticism is one thing; stupidity is another. But then, everyone is stupid about _something_.”

Ultimately, I think that Rickard’s assessment of Clarke was spot-on. He was interested in the facts that Fort accumulated, the various stories, and thought that there might be some scientific law to explain them—in the manner of Maynard Shipley and John W. Campbell. He was otherwise opposed to Fort’s more subversive elements.