The very model of a major . . . science-fictional Fortean.

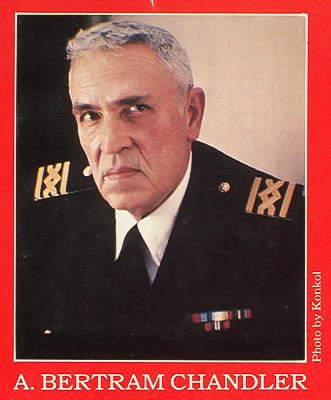

Arthur Bertram Chandler was born 28 March 1912 in Aldershot, Hampshire, England. He was the son of Arthur Robert Chandler, a soldier who died in World War I when he was only three, and the former Ida Florence Calver. Chandler grew up in in Beccles, Suffolk, with his brother, his mother, and his mother’s family, where he attended Peddar’s Lane Council School and Sir John Leman School. His maternal grandparents were either, he said, upper working class or lower middle class, and solidly invested in English class status—which he was not. Once, when he was a child, he was thrown out of the house for arguing about King Edward VII’s abdication of the English throne to marry. “But she’s only a commoner,” his grandmother said incredulously. “What the hell does it matter?,” he replied.

Aged sixteen, he left school; as he remembered it, he failed his exams to continue on because of the officiousness of either his teacher or headmaster, and late in life would wonder what his other path would look like. He went to work as an apprentice on a tramp steamer line, working his way to Second Mate. In the mid-1930s—about the time he was thrown out of the house—he returned to landlubbing work, briefly, as he could not find a job aboard a ship. This was the Depression, after all. He did return to the sea soon enough, though, joining Shaw Savill Lines as a Fourth Officer. Chandler married for the first time, 25 May 1938; his wife was Joan Margaret Barnard. His ship ran a line between England and Australasia. With the onset of war, he was a gunnery officer. He obtained his master’s certificate in 1943. Bertram and Joan had three children, two daughters and a son: Penelope, Christopher, and Jennifer (who married the horror writer Ramsey Campbell).

Arthur Bertram Chandler was born 28 March 1912 in Aldershot, Hampshire, England. He was the son of Arthur Robert Chandler, a soldier who died in World War I when he was only three, and the former Ida Florence Calver. Chandler grew up in in Beccles, Suffolk, with his brother, his mother, and his mother’s family, where he attended Peddar’s Lane Council School and Sir John Leman School. His maternal grandparents were either, he said, upper working class or lower middle class, and solidly invested in English class status—which he was not. Once, when he was a child, he was thrown out of the house for arguing about King Edward VII’s abdication of the English throne to marry. “But she’s only a commoner,” his grandmother said incredulously. “What the hell does it matter?,” he replied.

Aged sixteen, he left school; as he remembered it, he failed his exams to continue on because of the officiousness of either his teacher or headmaster, and late in life would wonder what his other path would look like. He went to work as an apprentice on a tramp steamer line, working his way to Second Mate. In the mid-1930s—about the time he was thrown out of the house—he returned to landlubbing work, briefly, as he could not find a job aboard a ship. This was the Depression, after all. He did return to the sea soon enough, though, joining Shaw Savill Lines as a Fourth Officer. Chandler married for the first time, 25 May 1938; his wife was Joan Margaret Barnard. His ship ran a line between England and Australasia. With the onset of war, he was a gunnery officer. He obtained his master’s certificate in 1943. Bertram and Joan had three children, two daughters and a son: Penelope, Christopher, and Jennifer (who married the horror writer Ramsey Campbell).

Chandler was a science fiction fan, and used his stops in New York as an opportunity to meet and chat up the editor of “Astounding,” John W. Campbell, who encouraged Chandler to try his hand at writing. Chandler made sure he made the grade as Master Mariner first, but then he followed Campbell’s advice. He “painfully pecked out” his first story on the way to New Zealand. When his ship again returned to New York, he submitted it to Campbell, and it was later published as “This Means War,” in the August 1944 issue. Not even six months later, he was in the magazine again, this time with a non-fiction essay, “The Perfect Machine,” about the magnetic compass, which appeared in January 1945.

Around this time, he joined the renascent British science fiction fandom, which had been hurt by the war. The group of aficionados had recently started meeting at the White Horse pub, “whose accommodations were larger and supply of beer more generous,” according to one account. Chandler entered the group at about the same time that Arthur C. Clarke did, as well as John Wyndham, and those attending began to call themselves the “London Circle.” (There was also a science fiction center in Liverpool.) According to one reminiscence, attendees passed around “beer stained” issues of the ‘zine “New Worlds” for the edification of Chandler and Clarke, this around December 1946.

By early 1947, he had put out an additional ten stories in “Astounding,” as well as others in Thrilling Wonder Stories (using the pseudonym George Whitley) and Short Stories. Most of his science fiction, he said, wasn’t “fantasy, but sea stories”: “built on my belief that space navigation will, when it comes, be much the same as sea navigation to-day. I feel that the astronaut will be more like the present-day seaman than the aviator, and that long voyages by men cooped up in great metal prisons will have the same end results whether they be ocean ships or space ships.”

He continued to write in a variety of American, British, and Australian magazines, sometimes going by A. Bertram Chandler, sometimes dropping the A; sometimes by George Whitley, sometimes using other pseudonyms: Andrew Dunstan, Paul T. Sherman, S. H. M. In the end, he would put out some 200 short stories—according to one calculation, in the 1950s he sold a story once every two weeks, on average—but was most famed for an early tale, “Giant Killer,” which ran in Astounding October 1945. He discussed science fiction at Rotary Club meetings in Australia, and befriended American science fiction fans. He also wrote regularly for Walter Gillings’s seminal British ‘zine “Fantasy Review.” More than a few of his stories were metafictional, involving characters named A. Bertram Chandler, or about sea-going science fiction writers, or lightly fictionalizing the White Horse.

Balancing fan activities, writing, sea-faring, and his personal life was difficult, it seems. He attended the “WhitCon,” Britain’s first post-war science fiction convention on 15 May 1948 (along with about 50 other people), but in July, his wife wrote in to “Fantasy Review” to give a new address for correspondence (in Cambridge) and “to express his regret that he has been unable to reply to recent letters owing to pressure of personal business.” By his own account—perhaps a joking reference, perhaps light humor to disguise real problems—she was not fond of his science fiction scribbling. He told the “Fantasy Review,” Joan “likes fantasy, but isn’t half so impressed with the work of Bertram Chandler as Bertram Chandler is.”

After Chandler reached the rank of chief officer, in the mid-1950s, his writing work—according to one account—stopped. There’s no break in the bibliography, but, then again, the timing of publishing and the timing of writing are often uncoupled. At the time, his marriage to Joan was also breaking down. In 1956, he moved to Australia, went to work for the Union Steamship Co. of New Zealand, and resumed his short fiction—in another account, his writing came after being “encouraged and bullied” by Susan Wilson, a designer, whom he married after his divorce to Joan was finalized, 23 December 1961, in Sydney. With the onset of all these changes, Chandler also tried his hand at a new form of science fiction, expanding to novels. The first, the elegiacally titled “Bring Back Yesterday” appeared in 1961. It would be followed by some 40 more. Australasia worked itself into his fiction, as the model for his Rim World. (Susan co-authored a couple of stories with him, and edited a volume too.)

Not long after he married, Chandler joined a naturist club. I do not know if he’d been a nudist for a long time, or just happened in to it, but he stayed with this particular club for more than two decades. It was of a piece with his general approach toward life, at least he explained it in the 1970s and 1980s: that he was a combination of “reactionary bastard” and also pleased progressive: that he generally leaned left, and valorized individual freedom. (He fits broadly into what I call left libertarianism.) He took “a dim view of progress for its own sweet sake.” Still, he thought of the past as, in many ways, the bad old days. He was pleased censorship laws in the U.S. and England had mostly been overturned (and chafed at their lingering hold in Australia); he disliked the designation working class—he was middle class, but he worked, at writing and sea faring—but detested even more England’s rigid class hierarchy and monarchism.

He worked on ships until retirement, in 1975. By that point, he was feted as a master of science fiction, winning Australian, American, and even a Japanese award for his writing—which by now was translated into many languages. He was a guest of honor at the science fiction world convention in 1982. And through this period, he continued to write. He had a novel published in 1984, as well as a short story based on the character for which he was most famed, John Grimes—a mix of Horatio Hornblower and himself, a captain who had relocated from an empire’s metropole to its edge.

Arthur Bertram Chandler died 6 June 1984 in Sydney, and was cremated. He was 72.

***************************

Chandler’s introduction to Fort and Forteanism is fairly clear, though Fort’s impact on him is perhaps more subtle than one would expect, at least at first blush. The community to which he belonged, British fandom, of course, was the natal home of British Forteanism, expanding from there to encompass occult and related communities. That would have nurtured Chandler’s interest in Fort, sustaining it. But he came to Fort before he joined the London Circle.

He discovered Fort in America, either prompted by Campbell or by his reading in science fiction, or both. As he tells it, when he met John W. Campbell in 1942, the science fiction editor encouraged him to try his hand at writing—Campbell was on the hunt for new talent and had plenty of space to fill in his magazines with the war effort redirecting his usual stable of writers. It is highly likely that Campbell pointed Chandler toward Fort: Campbell thought Fort was a good font of ideas for science fiction writers (he was not alone in this assessment), and the omnibus edition of Fort’s work had just come out in April 1941. Whether Campbell did recommend Fort or not, Chandler recounted that on his next visit to New York, some six months later, feeling comfortable with his master’s certificate in hand, he picked up the omnibus Fort “for light reading on our outward passage.” Something in the book gave him an idea for his first story, which he “slowly and painfully pecked out on the way to New Zealand.”

I have not seen the story, but accounts of it do not obviously suggest Fort. It is about Venusians who regularly visit the earth to mine materials beneath the North Seas. They come every century. In 1840, wooden ships did not endanger them, but in 1940, they are mistaken for German submarines and attacked. A few limp back to their home planet and tell the tale (in the best “I alone survived” tradition) and the concluding line is spoken by a Venusian: “This Means War.” While not evocative of Fort—beyond the concept of visiting aliens—the story does involve other Fortean themes, particularly that war breeds war—a view of pacifists such as Thayer—and presages the idea of Norman Markham that Venusians are using the planet as a source of necessary resources, and their activities, concentrated under oceans, cause earthquakes as well as the disappearance of vessels. More distantly, one can see ideas that would evolve into the speculations of Morris Jessup—again about extraterrestrials gathering materials from the earth—and Ivan Sanderson—that flying saucers might come from under the sea.

Fort’s ideas worked themselves into some of Chandler’s other fiction as well. His 1957 story for “Fantastic Universe” (incidentally literary home to many of Sanderson’s speculations about flying saucers and cryptozoology) included a reference to Fort. The story was about flying saucers, and one of the characters mentioned that Fort had recorded many such reports—but that the reports tended to follow the technology of the day, so that long ago they were considered supernatural phenomena, in the 1890s dirigibles, and, in the 1950s, space ships. His 1964 novel “Into the Alternate Universe” involves a Fortean Super-Sargasso Sea, which houses lost ships—from space and the ocean—which passed through a dimensional barrier. This story was part of his John Grimes series.

It would seem, then, that Chandler mostly used Fort as the Venusians used earth in his first story—a mine for necessities, a source of goods. He was, as far as I know, never a member of the Fortean Society, and never appeared in "Doubt." But there is evidence to suggest that Fortean ideas slipped into his thought more generally. Later in life, he remembered doing research for one Grimes novel, research on aeronautics during the era of the American Civil War. He was tracking down the experiments of two medical doctors, William Bland and Solomon Andrews. At the end of Chandler’s report on his archival research, he wrote, “It is interesting to note that although Dr. Bland first designed his dirigible—and made working models of it—in 1851, his final attempt to gain support for the project was made in 1866, shortly after Dr. Andrews’ successful flight over New York. Paraphrasing Charles Fort—It just wasn’t airship time!” Fort was a part of Chandler’s thoughts, not only a source of ideas, but also a voice commenting upon those ideas.

And Fort was more than that, too—he’d been absorbed in Chandler’s creed. Exactly how Fort fit into Chandler’s thought i have not completely sussed out, but his skepticism of official thought, willingness to entertain alternatives, and puckish humor all seem to have been appealing to Fort, as well as his historical speculations (since later Chandler novels were alternative histories, featuring what might be called the damned Antipodes). Late in life he would gloss his view on life and how to live it, a left-libertarian atheism that incorporated Fort: “I admit to being a Mobrist. MOBR is an acronym: My Own Bloody Religion. Take Swinburne’s ‘Holy Spirit of Man,’ add Wells’ ‘Race Spirit,’ flavour with infusions of Darwinism, Marxism and Buddhism, put into the blender, switch on and leave well alone except for, now and again, adding other ingredients such as Forteanism. And, even, Vonnegutism. So it goes.”

Around this time, he joined the renascent British science fiction fandom, which had been hurt by the war. The group of aficionados had recently started meeting at the White Horse pub, “whose accommodations were larger and supply of beer more generous,” according to one account. Chandler entered the group at about the same time that Arthur C. Clarke did, as well as John Wyndham, and those attending began to call themselves the “London Circle.” (There was also a science fiction center in Liverpool.) According to one reminiscence, attendees passed around “beer stained” issues of the ‘zine “New Worlds” for the edification of Chandler and Clarke, this around December 1946.

By early 1947, he had put out an additional ten stories in “Astounding,” as well as others in Thrilling Wonder Stories (using the pseudonym George Whitley) and Short Stories. Most of his science fiction, he said, wasn’t “fantasy, but sea stories”: “built on my belief that space navigation will, when it comes, be much the same as sea navigation to-day. I feel that the astronaut will be more like the present-day seaman than the aviator, and that long voyages by men cooped up in great metal prisons will have the same end results whether they be ocean ships or space ships.”

He continued to write in a variety of American, British, and Australian magazines, sometimes going by A. Bertram Chandler, sometimes dropping the A; sometimes by George Whitley, sometimes using other pseudonyms: Andrew Dunstan, Paul T. Sherman, S. H. M. In the end, he would put out some 200 short stories—according to one calculation, in the 1950s he sold a story once every two weeks, on average—but was most famed for an early tale, “Giant Killer,” which ran in Astounding October 1945. He discussed science fiction at Rotary Club meetings in Australia, and befriended American science fiction fans. He also wrote regularly for Walter Gillings’s seminal British ‘zine “Fantasy Review.” More than a few of his stories were metafictional, involving characters named A. Bertram Chandler, or about sea-going science fiction writers, or lightly fictionalizing the White Horse.

Balancing fan activities, writing, sea-faring, and his personal life was difficult, it seems. He attended the “WhitCon,” Britain’s first post-war science fiction convention on 15 May 1948 (along with about 50 other people), but in July, his wife wrote in to “Fantasy Review” to give a new address for correspondence (in Cambridge) and “to express his regret that he has been unable to reply to recent letters owing to pressure of personal business.” By his own account—perhaps a joking reference, perhaps light humor to disguise real problems—she was not fond of his science fiction scribbling. He told the “Fantasy Review,” Joan “likes fantasy, but isn’t half so impressed with the work of Bertram Chandler as Bertram Chandler is.”

After Chandler reached the rank of chief officer, in the mid-1950s, his writing work—according to one account—stopped. There’s no break in the bibliography, but, then again, the timing of publishing and the timing of writing are often uncoupled. At the time, his marriage to Joan was also breaking down. In 1956, he moved to Australia, went to work for the Union Steamship Co. of New Zealand, and resumed his short fiction—in another account, his writing came after being “encouraged and bullied” by Susan Wilson, a designer, whom he married after his divorce to Joan was finalized, 23 December 1961, in Sydney. With the onset of all these changes, Chandler also tried his hand at a new form of science fiction, expanding to novels. The first, the elegiacally titled “Bring Back Yesterday” appeared in 1961. It would be followed by some 40 more. Australasia worked itself into his fiction, as the model for his Rim World. (Susan co-authored a couple of stories with him, and edited a volume too.)

Not long after he married, Chandler joined a naturist club. I do not know if he’d been a nudist for a long time, or just happened in to it, but he stayed with this particular club for more than two decades. It was of a piece with his general approach toward life, at least he explained it in the 1970s and 1980s: that he was a combination of “reactionary bastard” and also pleased progressive: that he generally leaned left, and valorized individual freedom. (He fits broadly into what I call left libertarianism.) He took “a dim view of progress for its own sweet sake.” Still, he thought of the past as, in many ways, the bad old days. He was pleased censorship laws in the U.S. and England had mostly been overturned (and chafed at their lingering hold in Australia); he disliked the designation working class—he was middle class, but he worked, at writing and sea faring—but detested even more England’s rigid class hierarchy and monarchism.

He worked on ships until retirement, in 1975. By that point, he was feted as a master of science fiction, winning Australian, American, and even a Japanese award for his writing—which by now was translated into many languages. He was a guest of honor at the science fiction world convention in 1982. And through this period, he continued to write. He had a novel published in 1984, as well as a short story based on the character for which he was most famed, John Grimes—a mix of Horatio Hornblower and himself, a captain who had relocated from an empire’s metropole to its edge.

Arthur Bertram Chandler died 6 June 1984 in Sydney, and was cremated. He was 72.

***************************

Chandler’s introduction to Fort and Forteanism is fairly clear, though Fort’s impact on him is perhaps more subtle than one would expect, at least at first blush. The community to which he belonged, British fandom, of course, was the natal home of British Forteanism, expanding from there to encompass occult and related communities. That would have nurtured Chandler’s interest in Fort, sustaining it. But he came to Fort before he joined the London Circle.

He discovered Fort in America, either prompted by Campbell or by his reading in science fiction, or both. As he tells it, when he met John W. Campbell in 1942, the science fiction editor encouraged him to try his hand at writing—Campbell was on the hunt for new talent and had plenty of space to fill in his magazines with the war effort redirecting his usual stable of writers. It is highly likely that Campbell pointed Chandler toward Fort: Campbell thought Fort was a good font of ideas for science fiction writers (he was not alone in this assessment), and the omnibus edition of Fort’s work had just come out in April 1941. Whether Campbell did recommend Fort or not, Chandler recounted that on his next visit to New York, some six months later, feeling comfortable with his master’s certificate in hand, he picked up the omnibus Fort “for light reading on our outward passage.” Something in the book gave him an idea for his first story, which he “slowly and painfully pecked out on the way to New Zealand.”

I have not seen the story, but accounts of it do not obviously suggest Fort. It is about Venusians who regularly visit the earth to mine materials beneath the North Seas. They come every century. In 1840, wooden ships did not endanger them, but in 1940, they are mistaken for German submarines and attacked. A few limp back to their home planet and tell the tale (in the best “I alone survived” tradition) and the concluding line is spoken by a Venusian: “This Means War.” While not evocative of Fort—beyond the concept of visiting aliens—the story does involve other Fortean themes, particularly that war breeds war—a view of pacifists such as Thayer—and presages the idea of Norman Markham that Venusians are using the planet as a source of necessary resources, and their activities, concentrated under oceans, cause earthquakes as well as the disappearance of vessels. More distantly, one can see ideas that would evolve into the speculations of Morris Jessup—again about extraterrestrials gathering materials from the earth—and Ivan Sanderson—that flying saucers might come from under the sea.

Fort’s ideas worked themselves into some of Chandler’s other fiction as well. His 1957 story for “Fantastic Universe” (incidentally literary home to many of Sanderson’s speculations about flying saucers and cryptozoology) included a reference to Fort. The story was about flying saucers, and one of the characters mentioned that Fort had recorded many such reports—but that the reports tended to follow the technology of the day, so that long ago they were considered supernatural phenomena, in the 1890s dirigibles, and, in the 1950s, space ships. His 1964 novel “Into the Alternate Universe” involves a Fortean Super-Sargasso Sea, which houses lost ships—from space and the ocean—which passed through a dimensional barrier. This story was part of his John Grimes series.

It would seem, then, that Chandler mostly used Fort as the Venusians used earth in his first story—a mine for necessities, a source of goods. He was, as far as I know, never a member of the Fortean Society, and never appeared in "Doubt." But there is evidence to suggest that Fortean ideas slipped into his thought more generally. Later in life, he remembered doing research for one Grimes novel, research on aeronautics during the era of the American Civil War. He was tracking down the experiments of two medical doctors, William Bland and Solomon Andrews. At the end of Chandler’s report on his archival research, he wrote, “It is interesting to note that although Dr. Bland first designed his dirigible—and made working models of it—in 1851, his final attempt to gain support for the project was made in 1866, shortly after Dr. Andrews’ successful flight over New York. Paraphrasing Charles Fort—It just wasn’t airship time!” Fort was a part of Chandler’s thoughts, not only a source of ideas, but also a voice commenting upon those ideas.

And Fort was more than that, too—he’d been absorbed in Chandler’s creed. Exactly how Fort fit into Chandler’s thought i have not completely sussed out, but his skepticism of official thought, willingness to entertain alternatives, and puckish humor all seem to have been appealing to Fort, as well as his historical speculations (since later Chandler novels were alternative histories, featuring what might be called the damned Antipodes). Late in life he would gloss his view on life and how to live it, a left-libertarian atheism that incorporated Fort: “I admit to being a Mobrist. MOBR is an acronym: My Own Bloody Religion. Take Swinburne’s ‘Holy Spirit of Man,’ add Wells’ ‘Race Spirit,’ flavour with infusions of Darwinism, Marxism and Buddhism, put into the blender, switch on and leave well alone except for, now and again, adding other ingredients such as Forteanism. And, even, Vonnegutism. So it goes.”