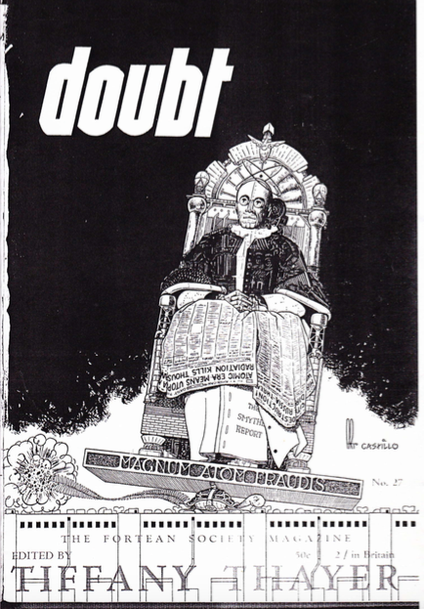

Cover of Doubt 27 (Winter 1949).

Cover of Doubt 27 (Winter 1949). A hard driving Fortean.

Arturo (Arthur) Castillo was born 3 November 1930 in Chicago. (Some reports have it as 30 November, but that is incorrect.) His mother was the former Dorothy Ada Rice, an artist an art teacher who attended the Art Institute of Chicago. His father was Servillano “Bill” Castillo, a postal worker who was born in the Philippines and immigrated to the United States in 1920, via Seattle, somehow ending up in the Midwest. (He studied at the University of Minnesota.) Bill had just turned 30 when Art was born; Dorothy was 26. They had been married just over a year. Art was their only child.

He attended Taft High School in Chicago, Illinois. I do not know if he had any more formal education, but he followed his mother’s interest and became an artist. His work was showcased in science fiction ‘zines, for he was also a devoted reader of science fiction, a member of fandom, where he promulgated his social and political ideas: generally speaking, leftist and anarchist. He had illustrations in “the Journal of Science-Fiction” no later than Fall 1952, which was based in Chicago, and probably other artwork in other ‘zines around the same time. In 1951, at least, he seems to have been living with William Donaho, who would go on to form the Berkeley ‘zine Habakkuk. (He gave Donaho’s address as his own in a letter to Eric Frank Russell.)

Arturo (Arthur) Castillo was born 3 November 1930 in Chicago. (Some reports have it as 30 November, but that is incorrect.) His mother was the former Dorothy Ada Rice, an artist an art teacher who attended the Art Institute of Chicago. His father was Servillano “Bill” Castillo, a postal worker who was born in the Philippines and immigrated to the United States in 1920, via Seattle, somehow ending up in the Midwest. (He studied at the University of Minnesota.) Bill had just turned 30 when Art was born; Dorothy was 26. They had been married just over a year. Art was their only child.

He attended Taft High School in Chicago, Illinois. I do not know if he had any more formal education, but he followed his mother’s interest and became an artist. His work was showcased in science fiction ‘zines, for he was also a devoted reader of science fiction, a member of fandom, where he promulgated his social and political ideas: generally speaking, leftist and anarchist. He had illustrations in “the Journal of Science-Fiction” no later than Fall 1952, which was based in Chicago, and probably other artwork in other ‘zines around the same time. In 1951, at least, he seems to have been living with William Donaho, who would go on to form the Berkeley ‘zine Habakkuk. (He gave Donaho’s address as his own in a letter to Eric Frank Russell.)

Early in 1952, he ran into some trouble. The details are sketchy, coming only from Doubt and letters that Tiffany Thayer wrote to Eric Frank Russell, but he either refused induction into the army or deserted—Thayer says both. The draft was still in effect, and active, inducting over a million and a half men between 1950 and 1953, the time of the Korean War. I have found no contemporary reports of the case in the press using on-line sources. Apparently, though, he was arrested and a trial was scheduled for 26 February 1952. He accepted, Thayer said, “limited service” as a conscientious objector. “Medical detail no doubt,” Thayer wrote to Russell in April.

In the mid-1950s, having finished his service, I guess, it seems that Castillo made his way to New York, where he became associated with he so-called “Fanarchists” and their publication “Coup.” Not much is known about the group, though it seems to have been centered around an apartment in Greenwich Village. Among the members was Trina Robbins, who would go on to fame as a comic artist. She and Art seemed to hit it off at the time, and she took his last name. (In personal correspondence, she attributed this to youthful enthusiasm—she was in her late teens—and not an actual marriage.) The relationship did not last very long, nor did the Fanarchists, who seem to have been active for only a few years, if that, around 1956 or 1957.

Castillo also contributed to “Inside and Science Fiction Advertiser,” another New York-based ‘zine, but it is not clear exactly when he was associated with it, and if it was via correspondence. I have found one contribution, from 1963, which must have been contributed earlier. Also associated with the ‘zine was another Fortean artist, Ralph Rayburn Phillips. “Inside and Science Fiction Advertiser” was especially focused on weird writings, such as by Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith. I’m not sure where Castillo was at the time, though he may have moved to the Bay Area. At any rate, both he and Trina—who was still using Castillo’s last name—became associated with the left-leaning Berkeley ‘zine Habakkuk. At some point, according to an obituary, he fathered a daughter, Cathleen Castillo, who lived in Chicago, possibly with distant family.

I have not seen copies of the ‘zine, but have seen reports, and both Art and Castillo seem to have been very active. The ‘zine began in early 1960 and featured art by both of them, as well as long articles by Art. In the fifth issue (or verse, as they were called), released December 1960, Art had a 28-page (!) article titled "An Inquiry into the Theory and Practice of Doublethink.” I have found one short excerpt: “Only under the conditions that produced this sweet paranoid dream could such fragmented concepts have arisen as Weiner's 'mechanism without matter’.” He also had a very long letter in the next verse, which appeared in July 1961. These would be interesting to see both to place Castillo geographically and politically. He was apparently a young revolutionary in the making. One of the forces behind “Xero,” a comics ‘zine, remembered Castillo accusing them of “relativistic Dadaism,” and complaining, “All around you is a society seething, begging not only for a critical evaluation of its fundamentals but for a reconstruction of those very fundamentals, and you people sit on your ass and discuss comic books. What’s wrong with you, anyway?”

Around this time—in 1959—Thayer reported that Castillo had relocated to Mexico, which suggests that he may have been contributing to Habakkuk from there. Certainly, he was writing letters—Thayer bitched that he was inundated with long letters from him. He then suffered a “lengthy” illness, which may have had him moving to Manhattan, Kansas, in June 1961,where his mother was living with her mother. These were difficult years for Dorothy. Her husband died in 1958. Her brother would die in 1962. And Art would not make it out of his thirties.

Arthur Castillo died 19 April 1962. He was 31. The editor of Habakkuk attributed the death to an “intestinal complaint.”

*********************

As with so many Forteans, I do not know when Castillo first encountered Fort, how he came to Forteanism, or when he joined the Fortean Society. It’s easy enough to speculate, of course. Running around in science fiction circles, involving himself un fan activities, Castillo had plenty of opportunities to stumble across Fort, Fortean ideas, or advertisements for the Society. The last—that he saw some announcement for the Society and looked into it—seems that most likely. For, at least as he displayed his ideas in Doubt, Castillo’s Forteanism seems to have been mostly political, and not scientific or playful. He wanted to take blasts at the powers-that-be. He wanted revolution. Even if that meant bringing the Society itself down.

Castillo’s first mention in the pages of Doubt came in issue 23, December 1948. He was credited with three contributions. One had to do with the story of Wonet; another with explosions; and a third with bird crashes. In no cases was his name attached directly to a report, but only included in a paragraph of members who had sent in material. Far more consequential was that a drawing by Castillo decorated the front cover. Apparently this was sent in unsolicited. (Maybe not.) Either way, it demonstrated familiarity with Thayer’s hobby-horses. The illustration showed a rain of his falling on the Mt. Palomar observatory. That may have been the worst of the ridicule, but not all of it. The observatory wore a clown hat, and strung around it was a sign: “Help the blind.” A cup of money sat just outside the observatory. All of this on a black background. (There was also a clothesline behind the observatory.) The fish fell out of a stream that may have been milk—suggesting the milky way or the popular but incorrect understanding of the old quote by Thoreau: “Some circumstantial evidence is very strong, as when you find a trout in the milk.”

In time, Castillo would become the Fortean Society’s primary illustrator. At the time, though, he seemed to have been gung-ho on the Society generally, not just drawing but organizing. Thayer noted in issue 23, “The artist who did the cover, Art Castillo, is energetically assembling the Forteans in and near Chicago with a view toward holding meetings. If you are interested, ask for his address.” This activity built on the earlier work of San Francisco Forteans who organized themselves into chapter two (acknowledging Thayer’s center as chapter one). Chicago would become chapter 3. Thayer reported on the activities of the Windy City’s Forteans in the following issue (which cover was a a blank white). This was in April 1949: “Chapter Three, Chicago: "No general meeting has been held, principally from lack of a hall, but members Castillo, Bump, Brady, Hurd and others are in organizational conferences pretty much all the time. The explosive potential is enormously greater than anything Lillienthal dreams of--what with provivisectionist ‘Ajax’ Carlson, anti-vaccinist Hurd, rocketeer Farnsworth and pro-Kantian Brady all wrestling in the same cyclotron."

Castillo also submitted a couple of reports for the issue. These are a little easier to to tie directly to him, though not perfectly, and they were all on subjects that had multiple members contributing reports. The first dealt with patients who exploded—or caught fire—after being treated with anasthesia. The second with cryptozoologist Ivan Sanderson who was studying mysterious footprints found on a beach in Florida. (Thayer was no fan of Sanderson.) The third was about Japanese confusion over which American books they were allowed to republish and how the press—or someone—made the confusion even worse by mis-reporting the title of a book by Faber Birren (A Fortean and friend of Thayer). Castillo also had a contribution in the next issue, 25, Summer 1949, re-used Castillo’s Palmer illustration as its front cover.

Issue 25 also started to use Castillo’s art as interior illustrations. Page 384 showed a picture titled Cerberus, which had the three-headed dog wearing three collars: church, state, and science. Behind the beast was a sign with “dogma” written backwards; below it were human bones. Dogma was a dog, a single beast though it might seem otherwise, that killed. Castillo included his own explanation, which Thayer ran beside it:

“When the Cerberus drawing is finally printed, I rather think some sort of special significance should be attached to it. It is, after all, a visual manifesto of the Society’s contemporary aims (which shall, in all likelihood, be valid for the next million or so years). That is to say, it points a direct finger at our triadic Opposition showing no partiality or favoritism whatsoever. Since the dawn of history the Unseen Empire has pretended that it was a heterogenous thing, merely a conglomeration of little Orthodoxies and Orthodox groups without much relation to each other except in their dogmatical stands. By presenting such a false picture Orthodoxy could befuddle its critics and enemies by getting them to assault merely some minor facade of the fortress while the rest of the monster escaped punishment. By so doing, anti-Orthodoxists were eft in the position of a martyring to catch with his bare handball the water that has fallen out of a bucket.

“Thus, those who attacked Church and State, like the atheist papers and more liberal publications, usually find themselves praising the greater glories of Dogmatic Science. While those who found materialistic science and the machinations of the so-called modern state twin atrocities usually find themselves defending the Church with fanatical zeal. And those who reject both religion and science usually find themselves wild-eyed ‘revolutionaries’ defending respect for the august state.

“Now, at last Forteans are enabled to see that all three are merely Orthodoxy in a different suit of clothes, and it seems to men that the heaviest Fortean emphasis should be on pointing out to anyone who cares to listen and digest it, that Church-State-Science are not three unrelated and different things, but departments subject to the same ‘cosmic’ chess-game, that the ludicrous settings on the world-stage are not solely the products of stupid leaders and mechanically idiotic masses, of dictators and popes and bank presidents and diplomats and countries squabbling over one thing and another, but the result of one and one only, esoteric control—a machination which George Malter melodramatically, but apropos, called the Unseen Empire. When more cataleptics and psycho-somatic robots substituting digestive tracts for brains can be made to see the entrenched unity behind all this artificial diversity, then, and only then, will any sort of ‘progress’ be made, or even started.”

One thing is clear: Castillo did not lack for confidence, in his art or his ideas. His ideas have a certain family resemblance to Fort’s in that they are (mostly?) monistic, seeing unity where others see only a collection—albeit Castillo’s ideas are much, much more paranoid. The reference to Malter suggests that Castillo, since he had joined the Fortean Society, was reading its approved literature—he was in the cause for the long haul, a million or so years, battling the secret empire that controlled the world. But Castillo’s cogitations are more akin to ideas that would be made more publicly in the 1960s, with attacks on “the system.” They also much back against trends in secularism and free thought—trends which Frederick Shroyer, for one, cheered on, the bludgeoning of religious (and mystical) ideas with science. Castillo wanted skepticism to be applied to science as well as religion and politics, a stance, in line with Thayer’s, that was increasingly fringe, even on the fringe.

Castillo amplified these ideas in another letter, which Thayer published just below his extended caption for “Cerberus”:

“Like the sham battle between industrialism and socialism, the idiotic capers about enforcing a ‘separation of church and state’ is too absurd for sane comprehension. Going to the table of State for crumbs after the manner of Scott [Nearing] and [Vashti] McCollum [other Forteans] merely lowers the prestige of one Authority and builds up that of the other. The Fortean Society is something unique in historical annals because it is the first association of philosophers and thinkers to succinctly point out just what our opposition is, rather than veering away like all the others or siding up with one department of Church-State-Science, and I humbly suggest that the broadness of that accusation be brought out much more vividly than the timid souls are wont to bring it.”

Castillo did not appear in Doubt again until issue 27, when again he illustrated the front cover. This image showed a robotic pope on a throne—labeled Magnum Atom Fraudis—with the Smythe Report and a newspaper on its lap, the headlines: “Destruction!,” “Russia Threat,” “Atomica era Means Utop[ia],” “Radiation Kills Thousands.” The whole assemblage sat on a turtle, which walked slowly, not knowing that a string of firecrackers was tied to its tail. Inside, were small illustrations: a robot whose brain exploded while studying a reading primer; an ice truck bombarded by huge falling icebergs; a riot of animals falling from the sky; a classroom scene of physicists playing dice behind a desk (probably a reference to Einsteins’ famous saying, “God does not play dice); a giant ball passing over a ship, the captain staring the wrong way through his looking-glass; Russian rocket, constructed from paper (?) and stamped “Made in Morristown”; an electronic computer, perched atop Mt. Olympus, with the read out “Deus ex Machina”; a plane, ballasted with a giant stone, praying (it didn’t crash); Freud winding up a toy man who shouted “Long Live Pavlov;” a crystal ball staring into the bald pate of human head bust; a Fortean Stamp titled “These Immortal Clowns . . . Inter baloney in Action” (0 c, “Post Office Hooey”) that showed Einstein and three other scientists I do not recognize slicing a tube of bologna; and a drawer bursting with Fortean phenomena: explosions, fish, birds, papers.

Castillo was also designing propaganda for the Fortean Society. Thayer announced, under title “Jesus Cards”: We have some cards in production suitable for holiday greetings at Christmas or any other time. Unfortunately, they cannot be ready for 19 FS [1949]. They are handsome reproductions of an Art Castillo drawing embodying the text of “Joking Jesus,” a poem by James Joyce. Very amusing, highly sacreligious [sic], they will be available shortly after the first of the year 20 F.S. Each card is the size of a page of DOUBT. The price is $1.00 for 13 cards, and that is the minimum order.”

Castillo’s art continued to appear in Doubt through the rest of the magazines run, sometimes prominently, sometimes not so much. Thayer re-used the interior art Castillo had already done; as well, new images appeared. He did a lot of covers: Doubt 28 should Abraham Michelson and Albert Einstein dancing, about to be hooked off the stage. Doubt 29 offered a new Fortean symbol, a tree branching through a question mark. (Thayer wrote: “The design on the cover, by Art Castillo, is an improvement over the old, plain question mark as a Fortean symbol. In this one a tree is growing. Catch? We are having some of these FS symbols printed on gummed paper like Christmas seals--for sticking on your outgoing mail to the uninitiated. There are other places they could be affixed. We don’t know the cost yet. Send whatever you wish and we;ll mail you a supply. The same symbol, with provocative, curiosity inciting legends attached, have been worked up into a cut-out book-mark. These are free. Ask for a supply, and put them in library books you read. Leave them between the pages when the books are returned.” Fortean Francis Bush printed the bookmarks and stickers.)

The cover of Doubt 31 played with Fort’s use of circle, with scientists arguing that eclipses can be predicted by clocks, and the accuracy of clocks checked by the revolution of the stars, which in turn is checked by the prediction of eclipses. Issue 33 showed religion and science—as Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dumb—shooting at and missing Velikovsky’s “Worlds in Collision,” which was depicted as a bird. Theology lay broken on the ground between them. Number 34 had a coat of arms, divided into four: one section had a silhouette of FDR, another of MacArthur. The other two read “I Hate War” and “War Makes Me Vomit.” It was captioned “Your Pacifist Shield.” Issue 35 had dogs vivisecting humans.

Doubt 39 began a series which ran under the Emerson quote “Science Does Not Know Its Debt to the Imagination.” This first showed science as a camera “struggling ever upwards towards the stars,” which were actually part of its own misshapen body. The second in the series appeared in issue 42, with a dead-looking science chimera lying on the floor, a jack-in-the-box where its head should be, and the caption “Science creating utopias for which man is not yet prepared.” The third came the following issue. Captioned “science peering under the surface of things,” it showed science on the bottom of a pancake-pile of stuff. Issue 44 had on its cover science, now depicted as monstrous shield, with dangling eyes and grasping hands, throttling a flower. This was “science triumphing over the forces of nature.” Two issues on, it was “science laying on good old American know how” that showed a twisted flag growing out of a mass of roots and sprouting both an axon-like appendage and an (all seeing?) eye. Another two issues on—Doubt 48—science looked like a giant tongue—it was “science speaking so that the mere layman can understand.” For Doubt 49, science was a twisted mass hiding behind its own hands, as a little man blew a raspberry at it: “science persecuted by the unlearned rabble.” There was a gap, and then issue 52 had science as a giant nose, on which was perched a small pair of glasses. Two tiny hands emerged from the ether, one holding a glass, the other pointing skyward. Castillo labeled this one “science godless monster such as the world has never beheld.” Issue 53 had science as a misshapen, monstrous bird, falling from the sky, and was titled “Science bringing its own guiding sprit to all mankind.” There was no Emerson quote with that cover—probably because of the bird’s size—but it returned the following issue, with another int he series, “science conscious of the smallness of its knowledge,” showing a bird-like head poking out from mountainous sheets, above two giant fists. That was the last in the series, and the last of Castillo’s covers.

In addition, Castillo penned a few comics—strips and single frames—that ran in Doubt for a little while. The first was the proposed Fortean stamp. In issue 29 he showed Einstein as Don Quixote tilting at windmills. In 29, his cartoon showed the USSR blowing up a balloon labeled “hydrogen bomb,” which it had gotten from the “Bigger Bogie Bureau,” while China stood sadly with its mere “uranium bomb” ballon. The Fortean Society was nearby, a pin hidden behind his back, ready to prick the “swollen bellies,” as Fort would have it. Doubt 30 had a comic by Castillo showing the Western and Eastern hemispheres led by demagogues (and supported by financiers) ready to regiment the people in the name of war, Cold War. Doubt 32 had the people of various countries sacrificing their freedoms for the good of the nation. A second coming int he same issue showed a bazaar, with various snake oil salesmen, including a physicist selling pictures of atoms and the journalist Henry J. Taylor claiming flying saucers were invented by the air force. For Doubt 33, a Castillo comic depicted the evolution of scientific war propaganda, from 1914 to 1951, culminating in the war coming to television.

The following issue called out Eric Frank Russell—and put on display Castillo’s political paranoia. He had a shady cabal of bankers meeting, one of them remarking on “Sinister Barrier” and its idea that a race of beings who rule the earth as farmers rule cows, and another responding, “How droll!” Science was a monkey performing for the crowd. In issue 35, he showed Orwell and Huxley looking over the goldfish bowl that was earth—a reference to Heinlein’s Fortean story, “The Goldfish Bowl,” perhaps—with Orwell remarking that the problem with their books was that they had set them in the future. A comic later in the issue mocked astronomers for not fully recognizing the possibility of life on other planets. The last of these comics appeared in issue 39 (January 1953), illustrating a passage from Max Planck’s autobiography which stated that new ideas in science were often accepted less because of convincing evidence and more because opponents died off. It showed him executing those who found fault with his ideas on quantum mechanics.

In Castillo’s account, these were tossed off, casual pieces. He told Russell in 1951, “None of that ‘art’-work has been intended for display in the sense of the ‘professional’ jobs sent to the larger magazines. It is usually done on any scrap of strathmore, bristol board or illustration matting that I can dig up, and by the time it gets to Thayer, good Mother Earth has been transferred from the ends of my left-handed fingers to the papers, the corners are worn, erasures have been committed, and an aura of general delapidation [sic] pervades the whole.

Eric Frank Russell was a fan from early on. Doubt 27 was one of his favorites, and, it seems, part of that was because of Castillo’s cover. Thayer responded to his letter of praise (the original letter is lost): “Right sweet of you to like #27 so much. It was well received here--also brought resignations--so it goes. Castillo is a prize. He keeps me loaded with stuff too. You shall have the original of the cover if you will frame and treasure it. On the walls of our first temple it should work miracles or, at the least, ooze oil.” As it happened, the original cover that Thayer sent to Russell was lost in the mail somewhere. (He may have sent the engraver’s proof, this isn’t clear from the correspondence.) But there would be other connections.

In the meantime, there were other difficulties with Castillo’s proposed art work, but they were enlightening. The Jesus cards were cancelled. Thayer reported in issue 28, “To a good many Forteans, Jesus Christ is a greta deal more than a myth, if something less than a God. Their attitude toward this personality out of ancient literature is epitomized by Art Young’s cartoon on the opposite page. They accept the historicity of this figure as proved, and his name has been more than once presented as that of a posthumous Fortean. As one MFS writes, “You say Forteanism is the perpetuation of dissent. Man alive, Christ was not only a great dissenter, his followers have dissented among themselves ever since he died dissenting.’ In recognition of the possible validity of these attitudes, and to free YS from any charge of attempting to force his personal atheism upon the membership, the projected Jesus cards, drawn by Castillo for the James Joyce poem, will not be published. US is an atheist, and of his own certain knowledge attests that so, too, was Charles Fort. YS cannot comprehend how an individual can reconcile Fort’s ‘eternally suspended judgment’ with the Christian necessity for absolute faith, but if some are able to work the mental adjustments to accommodate the apparently incompatible, that is their business. Never while YS lives shall atheism or any other article of faith or unfaith become a tenet of Forteanism to be embraced of necessity. Hence—no Jesus cards.” (In June 1950, Thayer reported to Russell that another member was thinking about sponsoring the Jesus cards, but nothing seems to have come of that.)

The concession was another battle in secularism and free thought that wended its way through Forteanism like a red thread. For the more immediate purposes, though, what stands out is the reference to Art Young. (The comic, by the way, was of a wanted poster for Jesus Christ, charging him with sedition, anarchy, and wanting to overthrow the established order.) Art Young was another of Thayer’s Fortean heroes—a Fortean in name only—but proves again that Thayer’s model for Doubt was the old magazine Puck, for which Fortean founder Harry Leon Wilson had worked. Thayer had an interest in comics, especially those with an editorial edge, and he was trying to cultivate Castillo to fit into this mold. He told Russell in February 1951, “Castillo is a real find, and we are working more closely together all the time.” He was also supporting another artist, Al Hall, and seemed to rely n him a bit more in the later 1950s.

Some time in the early 1950s, there arose the idea that Castillo might illustrate some of Russell’s works. In that same February 1951 letter, Thayer told Russell, “I put him on to your scheme to illustrate for you. Told him to write direct.” Apparently, the illustration had to to do with lie detectors, one of Thayer’s (many) bugaboos. Around the same time, Castillo was reaching out to Russell via the Society. He sent in another illustration, this one dedicated to Russell on the reverse. Thayer did not like it, though, thinking it “diffuse, like the Lord’s Prayer.” So it is not a surprise that Castillo wrote Russell in April of 1951, though he probably mis-calculated his approach, coming across as a jaded revolutionary and too critical by half. His letter began:

“Dear Eric Frank R:

“Thayer informed me a few months ago of your solicitous yen for illustrations to ornament one of your fantasies, spec., from me. I regret that I have not contacted you sooner on this matter but I’ve been somewhat preoccupied with investigating Sen. Kefauver, avoiding my draft board, mailing subversive literature to ministers, smuggling COs out of the country, reading Max Stirner, research on windmill generators, and other sad illnesses so that I’ve never sat down until now to punish my typewriter.”

The tone did not improve markedly in the second paragraph, when Castillo started to take shots at Russell’s professional work: “The reasons catalogued above have impeded you see any work on such a project, however it is my intention to execute these illustrations for you as soon as time permits. Not out of adoration for the pulps, you understand (or for that matter, with an eye towards touching rock bottom in the slicks). I merely abide by that celebrated American motto: ‘It’s a living.’

The third paragraph hit a crescendo of a sort, asking Russell to alter his work style to fit the illustrations: “In a sense, the project is further impeded by the somewhat hysteron proteron [sic] order of the task. It would be far easier, on both you and me, if you would think up a fantasy plot and mail me the skeletal outline. This way, I am forced to also think up a plot to roughly fit the illustrations . . . and if I had an idea that important I’d write it myself and send you to the devil.”

The final three paragraphs, though, which act as kind of a post-script—admittedly, as long as the letter—further the attacks, and showcase the perfect example of a backhanded thanks. It’s not a way to win a job:

“Incidentally I have just received your autographed DREADFUL SANCTUARY. Here you have a tremendous theme, probably the most profound ever put into a science-fiction story (matched only by Padgett’s MIMSY WERE THE BORGROVES) and all these points are excellently brought into the story. But why an Edgar Rice Burrough’s narrative written in an Anglish [sic] conception of U.S. slang (which, if you’ve ever heard American handlings [sic] of cockney, is rather startling)?

“I’ve read your shorter stories and many have been written in 14-karat english [sic]. I hope you don’t think I’m being nosy, but why do you write potboilers like great literature and write what could be great literature like potboilers? (If that’s what the Campbell clan want they should be strung up. I think Campbell’s beginning to believe his own delusions of grandeur; they’;; put him away one of these days).

“I notice that masses are swarming away from the Merry Old place to less strategic sections of the empale. Just what is going on over there?

“Forteanly yours, Art Castillo.”

From all I know of Russell, it seems that he would have been intensely irritated at the letter. But if so, he mostly swallowed it, presumably for the sake of working with Castillo. Either he liked him that much, or I am mis-reading his personality. (People are complex and weird!) He doesn’t seem to have bitched to Thayer, and did respond, apparently asking Castillo’s opinion on science fiction and showing continued interest in having him do some illustrations. But Castillo was surprised to see that he had only signed the letter “cordially.” Castillo wrote back in June, suggesting that Russell ask Thayer for the “lie detector” cover which he had dedicated to Russell and saying again he’d do the illustrations, though it would take several months. (As far as I know, there was never a collaboration between the two.) He continued to emphasize that he was doing the job strictly for the money. He had strong opinions on science fiction. Like Fritz Lieber—whom he liked and thought Fortean—he thought science fiction was moving away from the magazines and to books.

He thought science fiction had potential, but it was wasting away. Bradbury wrote legitimate literature; Del Rey could, but did not; Sturgeon did sometimes, but not consistently. There were earlier works by Wells and Stapleton and Moore and C.S. Lewis. It seems he held Campbell responsible for a lot of the problems in the field: “John Campbell is a source of amusement among Chicago Forteans and undergrads at the U of Chicago. In addition to his ‘atomic’ smog, his Einsteinium adulation, he composes some of the most asinine editorials in the business . . . (CAUSUS BELLI, to name but one). At any rate, life has taught John a great lesson. He’ll never promote another diabetics orgasm without first giving the author an aptitude test for criminal insanity and wife-beating. After all he has no less a confidence man than ray ‘Shaver-boy’- Palmer to contend with Now.”

He also had a dismissive view of British foreign policy as nothing more than an extension of American priorities, and clearly feared the world was on the brink go extinction:

“If many Britons regard their foreign policy as a reflex of Washington-Wall Street, Inc., they are correct. If Aneurin Bevan sez American armament is the world’s greatest threat to peace, he is correct. No Englisher would have donated arms to the Korean land-grab if American imperialists had not dominated the security council and slammed the table of the Federal Reserve hall. The fact that they couldn’t force the mercantilists to cut off China entirely shows a welcome strain of Titoism in your compatriots, commercial tho it be.” He ended the missive—the last of the correspondence, as far as I know—with some homework for Russell, on the impending population bomb (as it would later be called), recommending that he read William Vogt’s “Road to Survival” and Elmer Pendell’s “Population on the Loose.”

Given these political positions, it is not s surprise that Castillo would try to get out of serving in the Korean conflict. If it was all just a put-on by the financial elite, why risk one’s life? It was his dealings with the army that was the substance of his mentions in the Fortean Society during 1952 and 1953. Thayer mentioned his difficulties in Doubt 36 (April 1952) under the heading “Castillo in Toils” (evoking Prometheus in Chains, probably intentionally). At the time, Thayer promised future updates, but these never came to pass. Subsequent discussion was all conducted in letters. He mentioned thee troubles to Russell in April 1952, and said he would cover the matter in the next issue. But he did not. (The only mention of Castillo came in issue 39, January 1953, when the magazine’s art work was credited to him.) Thayer did not mention Castillo again until September 1953, in a letter to Russell, which clearly aimed at separating the Society and the artist. He began by apologizing for Castillo—probably meaning Castillo couldn’t do the art work for Russell, but also that there was less of his work in Doubt—and then explaining how Castillo’s problems had become the Society’s:

“He mishandled his army bout so badly that I can’t afford to risk being friendly until it is all settled. The damned fool deserted, and telegraphed me at the Fortean box for money, at a time when I was fending off postal inspectors and the FBI with both Spartan fists. Now I am studying Oriental Jiu-Jitsu, on your recommendation, and will wrestle them with my feet, like Confucius, but—no Castillo until the courts get through with him.”

It is true that Thayer had to deal with FBI investigations on and off throughout his career as publisher of Doubt, though his account here seems somewhat exaggerated. (Admittedly, though, when one is being investigated by the FBI, it may feel more ominous than it is in real life.) It is possible, as well, that a bigger rift developed between Castillo and the Society at about this time. His last comic strip appeared in January 1953. And there would be only one more mention of him, years later, when the break was complete. There would continue to be interior art work and covers, but it is possible Thayer was running material Castillo had sent in before. Certainly, nothing that came after Doubt 34—in 1953—was topical.

Castillo was not mentioned in Doubt again until the very last issue, when Thayer blasted him and Jack Green, the publisher of the New York periodical Newspaper. Unfortunately, my copy of this issue of Doubt cuts off the relevant page, making the article not quite clear. But the I get the gist. Thayer titled his screed “The New Scholiasts,” and went on to compare the two men to Pico della Mirandola, spewing forth “a wordy wrangle reminiscent of ye olden times or an undergraduate bull session wherein abstrusities are pitted against abstractions with a jejune sincerity that passes both belief and understanding.” He allowed that such yammering might be “good exercise for the intellect,” but was reluctant to weigh in since “the minutes of these meetings of the young minds are so damnably dull” he never finished. There was certainly a generation gap here, with Castillo about three decades younger than Thayer.

He went on, noting that “Art Castillo has been running around Mexico, writing me long, long, closely reasoned letters. The column gets hard to read from here, but it seems that Castillo worried that the world was caught between totalitarianism, nuclear war, and decompression. (There’s the rule of threes again!) The last of these had been suggested by Jack Jones, who wrote an article in “Newspaper” taking on Thayer for being a child; Castillo sent it to Thayer and suggesting Jones by a Named Fellow. Thayer, rolled his eyes, but acknowledged that there perhaps was something here, but he could not make sense of it, and he missed the literary brashness of Pound and Joyce, who also thumbed their nose at authority, but did so with panache. Curdling on the whole Fortean project as he had promoted it, Thayer suggested that Castillo take up the work of another Fortean, Albert Page, whose physical theories, he said, were as incomprehensible as those put forth by Green and Castillo.

Castillo’s objections to Thayer and the Fortean Society might be covered more in some of his writing for Habakkuk, which would have occurred just after Thayer penned his attack. There was no chance for it to appear in Doubt, because Thayer died of a heart attack in August 1959, and the Fortean Society pretty much closed up shot. There would not be a renascence for a few years, after which time Castillo tied.

Whatever the ending, though, Castillo was an important part of the Fortean Society, pushing its anarchism, providing a coruscating attack on all forms of authority, and foreshadowing positions to come. He was one of the few to put into practice something Thayer desperately wanted, Fortean art—Fortean art beyond science fiction. And so Thayer seemed willing to put up with a lot, at least until Castillo’s actions threatened the Society. That Thayer would turn on Castillo—and Castillo on Thayer—seems par for the course in both cases. Thayer almost always turned on those things he most liked, the Fortean Society itself being one of the rare exceptions, but its various members the usual targets. Castillo was by accounts hard driving and difficult. That the Society, seditious as it was, did not meet his criteria for true dissent does not surprise.

In the mid-1950s, having finished his service, I guess, it seems that Castillo made his way to New York, where he became associated with he so-called “Fanarchists” and their publication “Coup.” Not much is known about the group, though it seems to have been centered around an apartment in Greenwich Village. Among the members was Trina Robbins, who would go on to fame as a comic artist. She and Art seemed to hit it off at the time, and she took his last name. (In personal correspondence, she attributed this to youthful enthusiasm—she was in her late teens—and not an actual marriage.) The relationship did not last very long, nor did the Fanarchists, who seem to have been active for only a few years, if that, around 1956 or 1957.

Castillo also contributed to “Inside and Science Fiction Advertiser,” another New York-based ‘zine, but it is not clear exactly when he was associated with it, and if it was via correspondence. I have found one contribution, from 1963, which must have been contributed earlier. Also associated with the ‘zine was another Fortean artist, Ralph Rayburn Phillips. “Inside and Science Fiction Advertiser” was especially focused on weird writings, such as by Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith. I’m not sure where Castillo was at the time, though he may have moved to the Bay Area. At any rate, both he and Trina—who was still using Castillo’s last name—became associated with the left-leaning Berkeley ‘zine Habakkuk. At some point, according to an obituary, he fathered a daughter, Cathleen Castillo, who lived in Chicago, possibly with distant family.

I have not seen copies of the ‘zine, but have seen reports, and both Art and Castillo seem to have been very active. The ‘zine began in early 1960 and featured art by both of them, as well as long articles by Art. In the fifth issue (or verse, as they were called), released December 1960, Art had a 28-page (!) article titled "An Inquiry into the Theory and Practice of Doublethink.” I have found one short excerpt: “Only under the conditions that produced this sweet paranoid dream could such fragmented concepts have arisen as Weiner's 'mechanism without matter’.” He also had a very long letter in the next verse, which appeared in July 1961. These would be interesting to see both to place Castillo geographically and politically. He was apparently a young revolutionary in the making. One of the forces behind “Xero,” a comics ‘zine, remembered Castillo accusing them of “relativistic Dadaism,” and complaining, “All around you is a society seething, begging not only for a critical evaluation of its fundamentals but for a reconstruction of those very fundamentals, and you people sit on your ass and discuss comic books. What’s wrong with you, anyway?”

Around this time—in 1959—Thayer reported that Castillo had relocated to Mexico, which suggests that he may have been contributing to Habakkuk from there. Certainly, he was writing letters—Thayer bitched that he was inundated with long letters from him. He then suffered a “lengthy” illness, which may have had him moving to Manhattan, Kansas, in June 1961,where his mother was living with her mother. These were difficult years for Dorothy. Her husband died in 1958. Her brother would die in 1962. And Art would not make it out of his thirties.

Arthur Castillo died 19 April 1962. He was 31. The editor of Habakkuk attributed the death to an “intestinal complaint.”

*********************

As with so many Forteans, I do not know when Castillo first encountered Fort, how he came to Forteanism, or when he joined the Fortean Society. It’s easy enough to speculate, of course. Running around in science fiction circles, involving himself un fan activities, Castillo had plenty of opportunities to stumble across Fort, Fortean ideas, or advertisements for the Society. The last—that he saw some announcement for the Society and looked into it—seems that most likely. For, at least as he displayed his ideas in Doubt, Castillo’s Forteanism seems to have been mostly political, and not scientific or playful. He wanted to take blasts at the powers-that-be. He wanted revolution. Even if that meant bringing the Society itself down.

Castillo’s first mention in the pages of Doubt came in issue 23, December 1948. He was credited with three contributions. One had to do with the story of Wonet; another with explosions; and a third with bird crashes. In no cases was his name attached directly to a report, but only included in a paragraph of members who had sent in material. Far more consequential was that a drawing by Castillo decorated the front cover. Apparently this was sent in unsolicited. (Maybe not.) Either way, it demonstrated familiarity with Thayer’s hobby-horses. The illustration showed a rain of his falling on the Mt. Palomar observatory. That may have been the worst of the ridicule, but not all of it. The observatory wore a clown hat, and strung around it was a sign: “Help the blind.” A cup of money sat just outside the observatory. All of this on a black background. (There was also a clothesline behind the observatory.) The fish fell out of a stream that may have been milk—suggesting the milky way or the popular but incorrect understanding of the old quote by Thoreau: “Some circumstantial evidence is very strong, as when you find a trout in the milk.”

In time, Castillo would become the Fortean Society’s primary illustrator. At the time, though, he seemed to have been gung-ho on the Society generally, not just drawing but organizing. Thayer noted in issue 23, “The artist who did the cover, Art Castillo, is energetically assembling the Forteans in and near Chicago with a view toward holding meetings. If you are interested, ask for his address.” This activity built on the earlier work of San Francisco Forteans who organized themselves into chapter two (acknowledging Thayer’s center as chapter one). Chicago would become chapter 3. Thayer reported on the activities of the Windy City’s Forteans in the following issue (which cover was a a blank white). This was in April 1949: “Chapter Three, Chicago: "No general meeting has been held, principally from lack of a hall, but members Castillo, Bump, Brady, Hurd and others are in organizational conferences pretty much all the time. The explosive potential is enormously greater than anything Lillienthal dreams of--what with provivisectionist ‘Ajax’ Carlson, anti-vaccinist Hurd, rocketeer Farnsworth and pro-Kantian Brady all wrestling in the same cyclotron."

Castillo also submitted a couple of reports for the issue. These are a little easier to to tie directly to him, though not perfectly, and they were all on subjects that had multiple members contributing reports. The first dealt with patients who exploded—or caught fire—after being treated with anasthesia. The second with cryptozoologist Ivan Sanderson who was studying mysterious footprints found on a beach in Florida. (Thayer was no fan of Sanderson.) The third was about Japanese confusion over which American books they were allowed to republish and how the press—or someone—made the confusion even worse by mis-reporting the title of a book by Faber Birren (A Fortean and friend of Thayer). Castillo also had a contribution in the next issue, 25, Summer 1949, re-used Castillo’s Palmer illustration as its front cover.

Issue 25 also started to use Castillo’s art as interior illustrations. Page 384 showed a picture titled Cerberus, which had the three-headed dog wearing three collars: church, state, and science. Behind the beast was a sign with “dogma” written backwards; below it were human bones. Dogma was a dog, a single beast though it might seem otherwise, that killed. Castillo included his own explanation, which Thayer ran beside it:

“When the Cerberus drawing is finally printed, I rather think some sort of special significance should be attached to it. It is, after all, a visual manifesto of the Society’s contemporary aims (which shall, in all likelihood, be valid for the next million or so years). That is to say, it points a direct finger at our triadic Opposition showing no partiality or favoritism whatsoever. Since the dawn of history the Unseen Empire has pretended that it was a heterogenous thing, merely a conglomeration of little Orthodoxies and Orthodox groups without much relation to each other except in their dogmatical stands. By presenting such a false picture Orthodoxy could befuddle its critics and enemies by getting them to assault merely some minor facade of the fortress while the rest of the monster escaped punishment. By so doing, anti-Orthodoxists were eft in the position of a martyring to catch with his bare handball the water that has fallen out of a bucket.

“Thus, those who attacked Church and State, like the atheist papers and more liberal publications, usually find themselves praising the greater glories of Dogmatic Science. While those who found materialistic science and the machinations of the so-called modern state twin atrocities usually find themselves defending the Church with fanatical zeal. And those who reject both religion and science usually find themselves wild-eyed ‘revolutionaries’ defending respect for the august state.

“Now, at last Forteans are enabled to see that all three are merely Orthodoxy in a different suit of clothes, and it seems to men that the heaviest Fortean emphasis should be on pointing out to anyone who cares to listen and digest it, that Church-State-Science are not three unrelated and different things, but departments subject to the same ‘cosmic’ chess-game, that the ludicrous settings on the world-stage are not solely the products of stupid leaders and mechanically idiotic masses, of dictators and popes and bank presidents and diplomats and countries squabbling over one thing and another, but the result of one and one only, esoteric control—a machination which George Malter melodramatically, but apropos, called the Unseen Empire. When more cataleptics and psycho-somatic robots substituting digestive tracts for brains can be made to see the entrenched unity behind all this artificial diversity, then, and only then, will any sort of ‘progress’ be made, or even started.”

One thing is clear: Castillo did not lack for confidence, in his art or his ideas. His ideas have a certain family resemblance to Fort’s in that they are (mostly?) monistic, seeing unity where others see only a collection—albeit Castillo’s ideas are much, much more paranoid. The reference to Malter suggests that Castillo, since he had joined the Fortean Society, was reading its approved literature—he was in the cause for the long haul, a million or so years, battling the secret empire that controlled the world. But Castillo’s cogitations are more akin to ideas that would be made more publicly in the 1960s, with attacks on “the system.” They also much back against trends in secularism and free thought—trends which Frederick Shroyer, for one, cheered on, the bludgeoning of religious (and mystical) ideas with science. Castillo wanted skepticism to be applied to science as well as religion and politics, a stance, in line with Thayer’s, that was increasingly fringe, even on the fringe.

Castillo amplified these ideas in another letter, which Thayer published just below his extended caption for “Cerberus”:

“Like the sham battle between industrialism and socialism, the idiotic capers about enforcing a ‘separation of church and state’ is too absurd for sane comprehension. Going to the table of State for crumbs after the manner of Scott [Nearing] and [Vashti] McCollum [other Forteans] merely lowers the prestige of one Authority and builds up that of the other. The Fortean Society is something unique in historical annals because it is the first association of philosophers and thinkers to succinctly point out just what our opposition is, rather than veering away like all the others or siding up with one department of Church-State-Science, and I humbly suggest that the broadness of that accusation be brought out much more vividly than the timid souls are wont to bring it.”

Castillo did not appear in Doubt again until issue 27, when again he illustrated the front cover. This image showed a robotic pope on a throne—labeled Magnum Atom Fraudis—with the Smythe Report and a newspaper on its lap, the headlines: “Destruction!,” “Russia Threat,” “Atomica era Means Utop[ia],” “Radiation Kills Thousands.” The whole assemblage sat on a turtle, which walked slowly, not knowing that a string of firecrackers was tied to its tail. Inside, were small illustrations: a robot whose brain exploded while studying a reading primer; an ice truck bombarded by huge falling icebergs; a riot of animals falling from the sky; a classroom scene of physicists playing dice behind a desk (probably a reference to Einsteins’ famous saying, “God does not play dice); a giant ball passing over a ship, the captain staring the wrong way through his looking-glass; Russian rocket, constructed from paper (?) and stamped “Made in Morristown”; an electronic computer, perched atop Mt. Olympus, with the read out “Deus ex Machina”; a plane, ballasted with a giant stone, praying (it didn’t crash); Freud winding up a toy man who shouted “Long Live Pavlov;” a crystal ball staring into the bald pate of human head bust; a Fortean Stamp titled “These Immortal Clowns . . . Inter baloney in Action” (0 c, “Post Office Hooey”) that showed Einstein and three other scientists I do not recognize slicing a tube of bologna; and a drawer bursting with Fortean phenomena: explosions, fish, birds, papers.

Castillo was also designing propaganda for the Fortean Society. Thayer announced, under title “Jesus Cards”: We have some cards in production suitable for holiday greetings at Christmas or any other time. Unfortunately, they cannot be ready for 19 FS [1949]. They are handsome reproductions of an Art Castillo drawing embodying the text of “Joking Jesus,” a poem by James Joyce. Very amusing, highly sacreligious [sic], they will be available shortly after the first of the year 20 F.S. Each card is the size of a page of DOUBT. The price is $1.00 for 13 cards, and that is the minimum order.”

Castillo’s art continued to appear in Doubt through the rest of the magazines run, sometimes prominently, sometimes not so much. Thayer re-used the interior art Castillo had already done; as well, new images appeared. He did a lot of covers: Doubt 28 should Abraham Michelson and Albert Einstein dancing, about to be hooked off the stage. Doubt 29 offered a new Fortean symbol, a tree branching through a question mark. (Thayer wrote: “The design on the cover, by Art Castillo, is an improvement over the old, plain question mark as a Fortean symbol. In this one a tree is growing. Catch? We are having some of these FS symbols printed on gummed paper like Christmas seals--for sticking on your outgoing mail to the uninitiated. There are other places they could be affixed. We don’t know the cost yet. Send whatever you wish and we;ll mail you a supply. The same symbol, with provocative, curiosity inciting legends attached, have been worked up into a cut-out book-mark. These are free. Ask for a supply, and put them in library books you read. Leave them between the pages when the books are returned.” Fortean Francis Bush printed the bookmarks and stickers.)

The cover of Doubt 31 played with Fort’s use of circle, with scientists arguing that eclipses can be predicted by clocks, and the accuracy of clocks checked by the revolution of the stars, which in turn is checked by the prediction of eclipses. Issue 33 showed religion and science—as Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dumb—shooting at and missing Velikovsky’s “Worlds in Collision,” which was depicted as a bird. Theology lay broken on the ground between them. Number 34 had a coat of arms, divided into four: one section had a silhouette of FDR, another of MacArthur. The other two read “I Hate War” and “War Makes Me Vomit.” It was captioned “Your Pacifist Shield.” Issue 35 had dogs vivisecting humans.

Doubt 39 began a series which ran under the Emerson quote “Science Does Not Know Its Debt to the Imagination.” This first showed science as a camera “struggling ever upwards towards the stars,” which were actually part of its own misshapen body. The second in the series appeared in issue 42, with a dead-looking science chimera lying on the floor, a jack-in-the-box where its head should be, and the caption “Science creating utopias for which man is not yet prepared.” The third came the following issue. Captioned “science peering under the surface of things,” it showed science on the bottom of a pancake-pile of stuff. Issue 44 had on its cover science, now depicted as monstrous shield, with dangling eyes and grasping hands, throttling a flower. This was “science triumphing over the forces of nature.” Two issues on, it was “science laying on good old American know how” that showed a twisted flag growing out of a mass of roots and sprouting both an axon-like appendage and an (all seeing?) eye. Another two issues on—Doubt 48—science looked like a giant tongue—it was “science speaking so that the mere layman can understand.” For Doubt 49, science was a twisted mass hiding behind its own hands, as a little man blew a raspberry at it: “science persecuted by the unlearned rabble.” There was a gap, and then issue 52 had science as a giant nose, on which was perched a small pair of glasses. Two tiny hands emerged from the ether, one holding a glass, the other pointing skyward. Castillo labeled this one “science godless monster such as the world has never beheld.” Issue 53 had science as a misshapen, monstrous bird, falling from the sky, and was titled “Science bringing its own guiding sprit to all mankind.” There was no Emerson quote with that cover—probably because of the bird’s size—but it returned the following issue, with another int he series, “science conscious of the smallness of its knowledge,” showing a bird-like head poking out from mountainous sheets, above two giant fists. That was the last in the series, and the last of Castillo’s covers.

In addition, Castillo penned a few comics—strips and single frames—that ran in Doubt for a little while. The first was the proposed Fortean stamp. In issue 29 he showed Einstein as Don Quixote tilting at windmills. In 29, his cartoon showed the USSR blowing up a balloon labeled “hydrogen bomb,” which it had gotten from the “Bigger Bogie Bureau,” while China stood sadly with its mere “uranium bomb” ballon. The Fortean Society was nearby, a pin hidden behind his back, ready to prick the “swollen bellies,” as Fort would have it. Doubt 30 had a comic by Castillo showing the Western and Eastern hemispheres led by demagogues (and supported by financiers) ready to regiment the people in the name of war, Cold War. Doubt 32 had the people of various countries sacrificing their freedoms for the good of the nation. A second coming int he same issue showed a bazaar, with various snake oil salesmen, including a physicist selling pictures of atoms and the journalist Henry J. Taylor claiming flying saucers were invented by the air force. For Doubt 33, a Castillo comic depicted the evolution of scientific war propaganda, from 1914 to 1951, culminating in the war coming to television.

The following issue called out Eric Frank Russell—and put on display Castillo’s political paranoia. He had a shady cabal of bankers meeting, one of them remarking on “Sinister Barrier” and its idea that a race of beings who rule the earth as farmers rule cows, and another responding, “How droll!” Science was a monkey performing for the crowd. In issue 35, he showed Orwell and Huxley looking over the goldfish bowl that was earth—a reference to Heinlein’s Fortean story, “The Goldfish Bowl,” perhaps—with Orwell remarking that the problem with their books was that they had set them in the future. A comic later in the issue mocked astronomers for not fully recognizing the possibility of life on other planets. The last of these comics appeared in issue 39 (January 1953), illustrating a passage from Max Planck’s autobiography which stated that new ideas in science were often accepted less because of convincing evidence and more because opponents died off. It showed him executing those who found fault with his ideas on quantum mechanics.

In Castillo’s account, these were tossed off, casual pieces. He told Russell in 1951, “None of that ‘art’-work has been intended for display in the sense of the ‘professional’ jobs sent to the larger magazines. It is usually done on any scrap of strathmore, bristol board or illustration matting that I can dig up, and by the time it gets to Thayer, good Mother Earth has been transferred from the ends of my left-handed fingers to the papers, the corners are worn, erasures have been committed, and an aura of general delapidation [sic] pervades the whole.

Eric Frank Russell was a fan from early on. Doubt 27 was one of his favorites, and, it seems, part of that was because of Castillo’s cover. Thayer responded to his letter of praise (the original letter is lost): “Right sweet of you to like #27 so much. It was well received here--also brought resignations--so it goes. Castillo is a prize. He keeps me loaded with stuff too. You shall have the original of the cover if you will frame and treasure it. On the walls of our first temple it should work miracles or, at the least, ooze oil.” As it happened, the original cover that Thayer sent to Russell was lost in the mail somewhere. (He may have sent the engraver’s proof, this isn’t clear from the correspondence.) But there would be other connections.

In the meantime, there were other difficulties with Castillo’s proposed art work, but they were enlightening. The Jesus cards were cancelled. Thayer reported in issue 28, “To a good many Forteans, Jesus Christ is a greta deal more than a myth, if something less than a God. Their attitude toward this personality out of ancient literature is epitomized by Art Young’s cartoon on the opposite page. They accept the historicity of this figure as proved, and his name has been more than once presented as that of a posthumous Fortean. As one MFS writes, “You say Forteanism is the perpetuation of dissent. Man alive, Christ was not only a great dissenter, his followers have dissented among themselves ever since he died dissenting.’ In recognition of the possible validity of these attitudes, and to free YS from any charge of attempting to force his personal atheism upon the membership, the projected Jesus cards, drawn by Castillo for the James Joyce poem, will not be published. US is an atheist, and of his own certain knowledge attests that so, too, was Charles Fort. YS cannot comprehend how an individual can reconcile Fort’s ‘eternally suspended judgment’ with the Christian necessity for absolute faith, but if some are able to work the mental adjustments to accommodate the apparently incompatible, that is their business. Never while YS lives shall atheism or any other article of faith or unfaith become a tenet of Forteanism to be embraced of necessity. Hence—no Jesus cards.” (In June 1950, Thayer reported to Russell that another member was thinking about sponsoring the Jesus cards, but nothing seems to have come of that.)

The concession was another battle in secularism and free thought that wended its way through Forteanism like a red thread. For the more immediate purposes, though, what stands out is the reference to Art Young. (The comic, by the way, was of a wanted poster for Jesus Christ, charging him with sedition, anarchy, and wanting to overthrow the established order.) Art Young was another of Thayer’s Fortean heroes—a Fortean in name only—but proves again that Thayer’s model for Doubt was the old magazine Puck, for which Fortean founder Harry Leon Wilson had worked. Thayer had an interest in comics, especially those with an editorial edge, and he was trying to cultivate Castillo to fit into this mold. He told Russell in February 1951, “Castillo is a real find, and we are working more closely together all the time.” He was also supporting another artist, Al Hall, and seemed to rely n him a bit more in the later 1950s.

Some time in the early 1950s, there arose the idea that Castillo might illustrate some of Russell’s works. In that same February 1951 letter, Thayer told Russell, “I put him on to your scheme to illustrate for you. Told him to write direct.” Apparently, the illustration had to to do with lie detectors, one of Thayer’s (many) bugaboos. Around the same time, Castillo was reaching out to Russell via the Society. He sent in another illustration, this one dedicated to Russell on the reverse. Thayer did not like it, though, thinking it “diffuse, like the Lord’s Prayer.” So it is not a surprise that Castillo wrote Russell in April of 1951, though he probably mis-calculated his approach, coming across as a jaded revolutionary and too critical by half. His letter began:

“Dear Eric Frank R:

“Thayer informed me a few months ago of your solicitous yen for illustrations to ornament one of your fantasies, spec., from me. I regret that I have not contacted you sooner on this matter but I’ve been somewhat preoccupied with investigating Sen. Kefauver, avoiding my draft board, mailing subversive literature to ministers, smuggling COs out of the country, reading Max Stirner, research on windmill generators, and other sad illnesses so that I’ve never sat down until now to punish my typewriter.”

The tone did not improve markedly in the second paragraph, when Castillo started to take shots at Russell’s professional work: “The reasons catalogued above have impeded you see any work on such a project, however it is my intention to execute these illustrations for you as soon as time permits. Not out of adoration for the pulps, you understand (or for that matter, with an eye towards touching rock bottom in the slicks). I merely abide by that celebrated American motto: ‘It’s a living.’

The third paragraph hit a crescendo of a sort, asking Russell to alter his work style to fit the illustrations: “In a sense, the project is further impeded by the somewhat hysteron proteron [sic] order of the task. It would be far easier, on both you and me, if you would think up a fantasy plot and mail me the skeletal outline. This way, I am forced to also think up a plot to roughly fit the illustrations . . . and if I had an idea that important I’d write it myself and send you to the devil.”

The final three paragraphs, though, which act as kind of a post-script—admittedly, as long as the letter—further the attacks, and showcase the perfect example of a backhanded thanks. It’s not a way to win a job:

“Incidentally I have just received your autographed DREADFUL SANCTUARY. Here you have a tremendous theme, probably the most profound ever put into a science-fiction story (matched only by Padgett’s MIMSY WERE THE BORGROVES) and all these points are excellently brought into the story. But why an Edgar Rice Burrough’s narrative written in an Anglish [sic] conception of U.S. slang (which, if you’ve ever heard American handlings [sic] of cockney, is rather startling)?

“I’ve read your shorter stories and many have been written in 14-karat english [sic]. I hope you don’t think I’m being nosy, but why do you write potboilers like great literature and write what could be great literature like potboilers? (If that’s what the Campbell clan want they should be strung up. I think Campbell’s beginning to believe his own delusions of grandeur; they’;; put him away one of these days).

“I notice that masses are swarming away from the Merry Old place to less strategic sections of the empale. Just what is going on over there?

“Forteanly yours, Art Castillo.”

From all I know of Russell, it seems that he would have been intensely irritated at the letter. But if so, he mostly swallowed it, presumably for the sake of working with Castillo. Either he liked him that much, or I am mis-reading his personality. (People are complex and weird!) He doesn’t seem to have bitched to Thayer, and did respond, apparently asking Castillo’s opinion on science fiction and showing continued interest in having him do some illustrations. But Castillo was surprised to see that he had only signed the letter “cordially.” Castillo wrote back in June, suggesting that Russell ask Thayer for the “lie detector” cover which he had dedicated to Russell and saying again he’d do the illustrations, though it would take several months. (As far as I know, there was never a collaboration between the two.) He continued to emphasize that he was doing the job strictly for the money. He had strong opinions on science fiction. Like Fritz Lieber—whom he liked and thought Fortean—he thought science fiction was moving away from the magazines and to books.

He thought science fiction had potential, but it was wasting away. Bradbury wrote legitimate literature; Del Rey could, but did not; Sturgeon did sometimes, but not consistently. There were earlier works by Wells and Stapleton and Moore and C.S. Lewis. It seems he held Campbell responsible for a lot of the problems in the field: “John Campbell is a source of amusement among Chicago Forteans and undergrads at the U of Chicago. In addition to his ‘atomic’ smog, his Einsteinium adulation, he composes some of the most asinine editorials in the business . . . (CAUSUS BELLI, to name but one). At any rate, life has taught John a great lesson. He’ll never promote another diabetics orgasm without first giving the author an aptitude test for criminal insanity and wife-beating. After all he has no less a confidence man than ray ‘Shaver-boy’- Palmer to contend with Now.”

He also had a dismissive view of British foreign policy as nothing more than an extension of American priorities, and clearly feared the world was on the brink go extinction:

“If many Britons regard their foreign policy as a reflex of Washington-Wall Street, Inc., they are correct. If Aneurin Bevan sez American armament is the world’s greatest threat to peace, he is correct. No Englisher would have donated arms to the Korean land-grab if American imperialists had not dominated the security council and slammed the table of the Federal Reserve hall. The fact that they couldn’t force the mercantilists to cut off China entirely shows a welcome strain of Titoism in your compatriots, commercial tho it be.” He ended the missive—the last of the correspondence, as far as I know—with some homework for Russell, on the impending population bomb (as it would later be called), recommending that he read William Vogt’s “Road to Survival” and Elmer Pendell’s “Population on the Loose.”

Given these political positions, it is not s surprise that Castillo would try to get out of serving in the Korean conflict. If it was all just a put-on by the financial elite, why risk one’s life? It was his dealings with the army that was the substance of his mentions in the Fortean Society during 1952 and 1953. Thayer mentioned his difficulties in Doubt 36 (April 1952) under the heading “Castillo in Toils” (evoking Prometheus in Chains, probably intentionally). At the time, Thayer promised future updates, but these never came to pass. Subsequent discussion was all conducted in letters. He mentioned thee troubles to Russell in April 1952, and said he would cover the matter in the next issue. But he did not. (The only mention of Castillo came in issue 39, January 1953, when the magazine’s art work was credited to him.) Thayer did not mention Castillo again until September 1953, in a letter to Russell, which clearly aimed at separating the Society and the artist. He began by apologizing for Castillo—probably meaning Castillo couldn’t do the art work for Russell, but also that there was less of his work in Doubt—and then explaining how Castillo’s problems had become the Society’s:

“He mishandled his army bout so badly that I can’t afford to risk being friendly until it is all settled. The damned fool deserted, and telegraphed me at the Fortean box for money, at a time when I was fending off postal inspectors and the FBI with both Spartan fists. Now I am studying Oriental Jiu-Jitsu, on your recommendation, and will wrestle them with my feet, like Confucius, but—no Castillo until the courts get through with him.”

It is true that Thayer had to deal with FBI investigations on and off throughout his career as publisher of Doubt, though his account here seems somewhat exaggerated. (Admittedly, though, when one is being investigated by the FBI, it may feel more ominous than it is in real life.) It is possible, as well, that a bigger rift developed between Castillo and the Society at about this time. His last comic strip appeared in January 1953. And there would be only one more mention of him, years later, when the break was complete. There would continue to be interior art work and covers, but it is possible Thayer was running material Castillo had sent in before. Certainly, nothing that came after Doubt 34—in 1953—was topical.

Castillo was not mentioned in Doubt again until the very last issue, when Thayer blasted him and Jack Green, the publisher of the New York periodical Newspaper. Unfortunately, my copy of this issue of Doubt cuts off the relevant page, making the article not quite clear. But the I get the gist. Thayer titled his screed “The New Scholiasts,” and went on to compare the two men to Pico della Mirandola, spewing forth “a wordy wrangle reminiscent of ye olden times or an undergraduate bull session wherein abstrusities are pitted against abstractions with a jejune sincerity that passes both belief and understanding.” He allowed that such yammering might be “good exercise for the intellect,” but was reluctant to weigh in since “the minutes of these meetings of the young minds are so damnably dull” he never finished. There was certainly a generation gap here, with Castillo about three decades younger than Thayer.

He went on, noting that “Art Castillo has been running around Mexico, writing me long, long, closely reasoned letters. The column gets hard to read from here, but it seems that Castillo worried that the world was caught between totalitarianism, nuclear war, and decompression. (There’s the rule of threes again!) The last of these had been suggested by Jack Jones, who wrote an article in “Newspaper” taking on Thayer for being a child; Castillo sent it to Thayer and suggesting Jones by a Named Fellow. Thayer, rolled his eyes, but acknowledged that there perhaps was something here, but he could not make sense of it, and he missed the literary brashness of Pound and Joyce, who also thumbed their nose at authority, but did so with panache. Curdling on the whole Fortean project as he had promoted it, Thayer suggested that Castillo take up the work of another Fortean, Albert Page, whose physical theories, he said, were as incomprehensible as those put forth by Green and Castillo.

Castillo’s objections to Thayer and the Fortean Society might be covered more in some of his writing for Habakkuk, which would have occurred just after Thayer penned his attack. There was no chance for it to appear in Doubt, because Thayer died of a heart attack in August 1959, and the Fortean Society pretty much closed up shot. There would not be a renascence for a few years, after which time Castillo tied.

Whatever the ending, though, Castillo was an important part of the Fortean Society, pushing its anarchism, providing a coruscating attack on all forms of authority, and foreshadowing positions to come. He was one of the few to put into practice something Thayer desperately wanted, Fortean art—Fortean art beyond science fiction. And so Thayer seemed willing to put up with a lot, at least until Castillo’s actions threatened the Society. That Thayer would turn on Castillo—and Castillo on Thayer—seems par for the course in both cases. Thayer almost always turned on those things he most liked, the Fortean Society itself being one of the rare exceptions, but its various members the usual targets. Castillo was by accounts hard driving and difficult. That the Society, seditious as it was, did not meet his criteria for true dissent does not surprise.