A mysterious disappointment over a Fortean figurehead.

Anton J Carlson, a long-time physiologist at the University of Chicago is well-known in scientific circles, his life well-documented. Most assuredly less known in standard biographies is his association with the Fortean Society—I have not seen a single reference—and still more mysterious is why Tiffany Thayer felt disappointed in his activities, especially given that Carlson was mostly a figurehead for the Society, a trophy, whose contributions seem to extend only to including the Society among those to whom he sent reprints of his articles. Oh, and paying dues, for a while.

First, though, before a quick overview of Carlson’s life, let’s clear up another bit of possible confusion. Thayer announced that Carlson had joined the Society in Doubt 20 (March 1948); in the course of that announcement, he mentioned that there were two other by that name connected to the Society, of which he only named one, the former Marine Evans Fordyce Carlson. Before this issue, as early as 1946, Thayer mentioned a member named Carlson, with no other identifying information. Later, almost—but not all—the clippings were attributed to a “D. Carlson.” It seems likely that neither Anton J. (“Ajax”) or Evans Fordyce contributed clippings to the Society. More on those other Carlsons in later entries.

Anton J Carlson, a long-time physiologist at the University of Chicago is well-known in scientific circles, his life well-documented. Most assuredly less known in standard biographies is his association with the Fortean Society—I have not seen a single reference—and still more mysterious is why Tiffany Thayer felt disappointed in his activities, especially given that Carlson was mostly a figurehead for the Society, a trophy, whose contributions seem to extend only to including the Society among those to whom he sent reprints of his articles. Oh, and paying dues, for a while.

First, though, before a quick overview of Carlson’s life, let’s clear up another bit of possible confusion. Thayer announced that Carlson had joined the Society in Doubt 20 (March 1948); in the course of that announcement, he mentioned that there were two other by that name connected to the Society, of which he only named one, the former Marine Evans Fordyce Carlson. Before this issue, as early as 1946, Thayer mentioned a member named Carlson, with no other identifying information. Later, almost—but not all—the clippings were attributed to a “D. Carlson.” It seems likely that neither Anton J. (“Ajax”) or Evans Fordyce contributed clippings to the Society. More on those other Carlsons in later entries.

Ajax Carlson was born 29 January 1875 in Sweden, which makes him just a bit younger than Charles Fort. Life was hard there, the family eking out an existence as farmers. Around the time Ajax turned 16, his brother had settled in Chicaho and was working as a carpenter; Ajax followed. He saved his money for a few years, learned enough English, and then attended Augustana Academy and College, a Lutheran school, finishing in 1899. Raised as a strict Lutheran since childhood, he considered going to seminary—an obvious rout for someone of bookish inclinations—but, as the legend goes, found the Lutherans to skeptical of empiricism: he proposed testing the efficacy of prayer for rain by having some congregations pray for it, others not, and measure the results against yearly averages, which raised some eyebrows among his co-religionists.

After some time nonetheless working as a substitute minister, Ajax decided the part of education that excited him most was physiology, and he found his way to the relatively new Stanford University, where he worked partly under the school’s president David Starr Jordan, studying nerve conduction. He received his Ph.D. in 1902. He then moved to the Carnegie Institution, where he studied the interaction of the heart of nerves, and carried out various research projects during the summer months. In 1904, he was invited to join the University of Chicago, itself something of a new institution, and on the make. He would stay there the rest of his career, rebuffing frequent offers from other universities to move his laboratory. In 1905, he married Esther Naioma Sjogren, whom he had known since Augusta, and they would have three children: Robert, who became a businessman, Alvin, a chest surgeon, and Alice, the wife of Professor Hough of the University of Illinois.

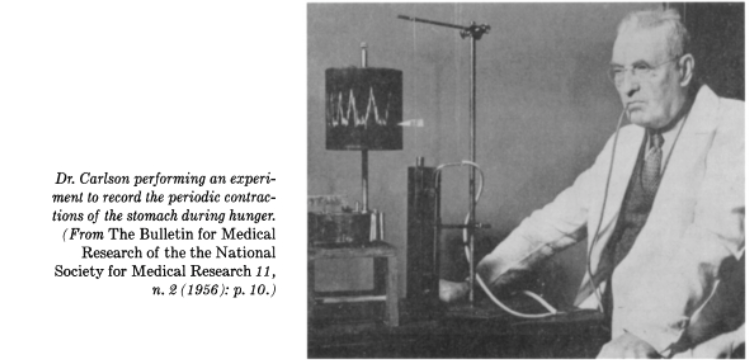

As the legend of his break from Lutheranism would have it, Ajax was a dedicated empiricist, careful of over theorizing and always demanding evidence for assertions. With the coming of World War I, he became concerned over issues of food and hunger, and experimented on himself, swallowing a balloon, attaching it, via a tube that ran down his throat, to machines so that he could measure stomach contractions and gastric juice production. He was also an activist from early on: he worked with the government to regulate saccharin in foodstuffs; he warned about the dangers of pesticide residues, maple syrup adulterated with lead and popcorn coated with mineral oil rather than butter. He tried to get a lunch program started in Chicago’s schools for poor children, and was involved with the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. He also served on many scientific boards.

By the time he retired in 1940, he had taught some 5,000 medical students and been involved with graduating 151 MS students and 112 Ph.D.s. Peter J. Kuznick, the historian, points out many of these graduates shared Carlson’s broadly left wing perspective. His empiricism put him at odds with the hierarchy of the University of Chicago, particularly the president Robert Hutchins and his associate Mortimer Adler. They had become skeptical of empiricism to solve problems and wanted a return to the philosophies of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. He also suggested ending tenure, which Ajax opposed. Ajax was critical of the educational system—turning out automatons, he suggested—but also deeply loyal to its principles, and served in the American Association of University Professors.

Similarly, Carlson could be deeply critical of America—but always reaffirmed that he was an American by choice and loved his country. In the 1940s, he again became involved with a series of battles between the government and the makers of snake-oil nostrums. He detested “enriched” bread, which he thought added back only a fraction of the nutrients stripped to make white flour in the first place. Having seen the horrors of World War I, he was a peace advocate. He was called before the House Un-American Committee and the Senate committee investigating communism in higher education, and blasted both as un-transparent and un-American. He stood up for doctors drafted into the Army because they refused to sign loyalty oaths.

Carlson kept busy with his many investigations—mostly clinical by this point, as opposed to laboratory—in the years after his mandatory retirement at age 65. (Indeed, one of his causes was pointing out the absurdity of forcing retirement to people at that age.) He claimed to work 18 hours per days until 1952, when a heart attack made him cut back. He gave numerous lectures, wrote two books and over 250 scientific articles.

One of his causes that stands out against the background of Forteanism is his devotion to Humanism. As Humanism developed in America during the late 1920s and 1930s, it was not initially completely secular nor skeptical in the sense of the modern skeptical movement, which tries to debunk pseudoscience: in fact, one part of the humanist movement was worried over science and technology’s creation of deadly weapons. To be sure, the original Humanist Manifesto of 1933 insisted that life originated through organic evolution and ruled out the need for supernatural forces, but the membership was more eclectic than the manifesto allowed, and at least some of the founders were seekers of one sort or another. The movement was also anti-capitalist, though not communist.

Carlson was one of the signatories of the original manifesto, and many of his speeches extolled the importance of creative activity—and work. (He explained his own longevity as 3W-3D: Work, Work, Word, Diaper Days to Death.) Previous to that, he presented “The William Vaughn Moody” lecture at the University of Chicago on “Science and the Supernatural,” subsequently published in the journal “Science.” It showed him to be no friend of religion, and also aware of science’s limits: science approximates the truth as best as any human production can, dependent upon a method of controlling variables and investigator honesty. Religion, on the contrary, is made up of revelations that are often erroneous and offer no testable forms of knowledge. At best, scientists can ignore religion as a series of statements of no particular interest. At worst, they have to fight against religion as something that stands against the development of knowledge. The persistence of religion to this day, Carlson suspects, is a relic: all humans, all human societies, go through a religious phase. But it is a childish thing, and should be set aside when one is no longer a child.

Anton J. Carlson died 2 September 1956 of cancer. He was 81.

So what can we say of Carlson as a Fortean? It is unclear how Carlson ever came to Charles Fort’s books, if he read them at all. The (relatively) small Humanist community did overlap the (even smaller) Fortean community, but the connections I can document don’t come until the mid to late 1940s. The earliest is from 1944, which is a couple of years before Ajax joined, making it possible that he heard of Fort through this rout. More likely, Thayer approached him: Carlson was publicly known (featured on a 1941 cover of “Time” magazine) and Thayer recognized some of the affinities between the Humanist movement and Forteanism, even if he did not always appreciate the Humanists and their allies. Nothing in the pages of Doubt make me think that Carlson was a partisan of Fort, and I have seen no references to Fort in his own writing. Certainly, Fort’s empiricism might have intrigued him; likely his theories—speculative although they were—would have turned him off.

Thayer was excited to announce Carlson’s joining the Society in March 1948—it was that double-edged sword of Forteanism (and other fringe groups): disparaging science, but then trumpeting when recognized by science or scientists. The same thing had happened earlier when Dr. Frederick S. Hammett joined. They made the announcement in the midst of a column documenting the Society’s recent successes: “And--to top all--Dr. Anton J. Carlson, professor emeritus of U of Chicago, ex president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, joined the Fortean Society on the democratic level of corresponding membership--just like an ordinary mortal . . . Can anyone doubt our manifest destiny?.” (Thayer made similar noises in Doubt 41, July 1953, touting Carlson’s membership as more proof of the Societies strides.)

In that initial announcement, Thayer continued, “Our new Carlson sends a small basket of pamphlets--reprints of his lectures and articles. They display as pure a Forteanism as Fort himself possessed--roughly, the percentage figure made so well known by the ads for Ivory Soap. ... On 12-29-47 old style, the Dr. busted into the papers by telling the AA for the AS that white bread contained ‘nerve poison.’ Clearly he is not in the pay of the bread trust, nor an intimate of Truman’s physician.” Thayer and Eric Frank Russell—among others—were keenly skeptical of industrialized food, especially bread. (Henry Miller rote an entire essay decrying the horrors of American bread compared to what he could find in France.) And so on that point alone, Carlson was a welcome voice. A year later, Thayer wrote to Russell repeating Carlson’s warnings, and admitting that he himself only ate rye bread, so afraid was he off what was the the new staff of life. Thayer made the association, again, between bread and Carlson at Russell’s prompting in issue 33 (October 1951): after Russell complained about the poor quality of food available in post-War England, Thayer advised readers, “Ask your local Health Officer, family doctor, or MFS ‘Ajax’ Carlson how flour is bleached and processed in America!”

Of the may recurrences of the name “Carlson” in Doubt during subsequent years, only Four of them can be definitely attributed to Ajax. The first was a passing mention in the context of some Chicago Forteans possibly organizing themselves into a chapter. Thayer thought the potential explosive, among other reasons because on Chicago Fortean was against vaccinations and Ajax was for vivisection—the use of animals in experiments—a cause that Thayer himself championed against. That was in Doubt 24 (April 1949), and clearly reflected Thayer’s fantasies more than the reality that Carlson might have entertained the notion of meeting with other Forteans. (In fact, there is no evidence that the Chapter ever met.) The second mention was of another reprint being offered for sale. Doubt 30 (October 1950) relayed, “MFS ‘Ajax’ Carlson, former president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, has donated to the Society a few copies of a pamphlet, a reprint of his essay on Science, Education, and the Future of Man. While they last--25 cents each.

The other two mentions are more substantive, bookends of a sort: though also launchpad for a mystery. Frederick Hammett died in 1953, and Thayer told Russell that Ajax had agreed to replace him as an Honorary Founder of the Fortean Society (filling the seat originally held by Booth Tarkington). There’s a suggestion that Thayer was still genuinely proud of this connection: he bragged to Russell that Doubt 41 (July 1953), the issue with the announcement of Ajax’s elevation, was the best ish ever, to my way of thinking. Meaty as the southwest corner of a hog.” And the announcement was as full-throated as his initial acceptance of Carlson into the Fortean fold: Hammett had been “the living bridge between Forteanism and capital ’S’ Science, our foot-in-the-door of Orthodoxy” and Carlson was a perfect replacement: “Now that he has the blessing of the Damned as well, he is indeed a complete man.”

Only three years later, though, Carlson himself would pass, without his name ever having appeared in Doubt until his obituary, which was the first to sound the note of Thayer’s disappointment. From Doubt 53 (February 1957): “Then we lost out newest Honorary Founder, the celebrated ‘Ajax’ Carlson of Chicago. It would be quite useless for us to recap the career of Dr. Carlson. The Scientific press has done that ad nauseum. For a few of his honors see DOUBT #41. Unfortunately Dr. Carlson did not live up to our expectations of him after accepting the post of Honorary Founder but we lack the space to go into detail. Our problem now is to find a successor operating within the Sacred Circles of Science. Suggestions are solicited and our progress will be reported.”

And there is the mystery. What were Thayer’s expectations, and how did Carlson fail to meet them? Certainly, there were differences in viewpoint between the two men, but much of that was long-standing, known to Thayer since accepting Carlson and (presumably) reading his reprints. Carlson was a vivisectionist, Thayer not. Carlson was patriotic, Thayer not. Carlson thought good science could at least approximate truth, Thayer did not. Did Thayer expect Carlson to give up these beliefs? That seems unlikely. And unlike Ben Hecht, whose public actions Thayer also did not like, Carlson does not seem to have done anything after 1953—when he became and Honorary Founder—as out of character as Hecht cheering on the foundation of Israel. He continued to complain about the poor quality of American food—dog’s eat better, he said—and blamed it for the growth of obesity (1 in 5 Americans was overweight), the prevalence of so much food in such variety making people fat. He worried over alcoholism, but was not a prohibitionist, recommending a glass of alcohol a day and noting he was a moderate imbiber. (Two glasses was a waste, three caused poisoning.) These might have irritated Thayer slightly, but they were of a piece with what Carlson had been saying for years. And Thayer himself followed Carlson’s 3W-3D recommendations, even if he didn’t credit Ajax, working hours on end every day.

It is possible that Carlson’s connection with the Humanist movement grated on Thayer. In 1953, Carlson was named the first ever Humanist of the Year, by the American Humanist Association (whose magazine, the Humanist, was run by Edwin H. Wilson, a Fortean). That same year, The Humanist published a symposium on the Humanist Manifesto at 20, with recommendations for changes. Carlson recommended that point 14 be altered, as it reeked too much of the Great Depression and was not so relevant anymore. It’s possible Thayer heard about this suggestion and objected, since he was no fan of the capitalist system that point 14 attacked, but all of that seems a little too picayune. The point read: “FOURTEENTH: The humanists are firmly convinced that existing acquisitive and profit-motivated society has shown itself to be inadequate and that a radical change in methods, controls, and motives must be instituted. A socialized and cooperative economic order must be established to the end that the equitable distribution of the means of life be possible. The goal of humanism is a free and universal society in which people voluntarily and intelligently cooperate for the common good. Humanists demand a shared life in a shared world.” He also thought the document should stress the social responsibility of the individual more than it had—which would be in line with his own activities but also would have gone against the grain of Thayer’s more individualistic, voluntaristic ethos.

The best explanation I can come up with, and it’s not a great one, is that Thayer was disappointed that Carlson did not point out the shortcomings of science as much as he would have liked. Hammett had, and had even cited Fort in some of his papers. Carlson seemed (based on my superficial reading of the record) to have become more accepting of science, less likely to equivocate, and more dismissive of scientific ignoramuses, the number of whom he thought was growing. An obituary quoted him saying,” “The great mass of people of our age, even in the most enlightened countries, in their thinking and their motivation, are nearly as untouched by the spirit of science and as innocent of the understanding of science, as was Peking man.” That’s the kind of scientific triumphalism that would set Thayer’s teeth on edge. The problem with this hypothesis is that the quotation can be traced back to 1938, at least. So was the problem just that Thayer wanted Carlson to change, but the scientist refused?

After some time nonetheless working as a substitute minister, Ajax decided the part of education that excited him most was physiology, and he found his way to the relatively new Stanford University, where he worked partly under the school’s president David Starr Jordan, studying nerve conduction. He received his Ph.D. in 1902. He then moved to the Carnegie Institution, where he studied the interaction of the heart of nerves, and carried out various research projects during the summer months. In 1904, he was invited to join the University of Chicago, itself something of a new institution, and on the make. He would stay there the rest of his career, rebuffing frequent offers from other universities to move his laboratory. In 1905, he married Esther Naioma Sjogren, whom he had known since Augusta, and they would have three children: Robert, who became a businessman, Alvin, a chest surgeon, and Alice, the wife of Professor Hough of the University of Illinois.

As the legend of his break from Lutheranism would have it, Ajax was a dedicated empiricist, careful of over theorizing and always demanding evidence for assertions. With the coming of World War I, he became concerned over issues of food and hunger, and experimented on himself, swallowing a balloon, attaching it, via a tube that ran down his throat, to machines so that he could measure stomach contractions and gastric juice production. He was also an activist from early on: he worked with the government to regulate saccharin in foodstuffs; he warned about the dangers of pesticide residues, maple syrup adulterated with lead and popcorn coated with mineral oil rather than butter. He tried to get a lunch program started in Chicago’s schools for poor children, and was involved with the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. He also served on many scientific boards.

By the time he retired in 1940, he had taught some 5,000 medical students and been involved with graduating 151 MS students and 112 Ph.D.s. Peter J. Kuznick, the historian, points out many of these graduates shared Carlson’s broadly left wing perspective. His empiricism put him at odds with the hierarchy of the University of Chicago, particularly the president Robert Hutchins and his associate Mortimer Adler. They had become skeptical of empiricism to solve problems and wanted a return to the philosophies of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. He also suggested ending tenure, which Ajax opposed. Ajax was critical of the educational system—turning out automatons, he suggested—but also deeply loyal to its principles, and served in the American Association of University Professors.

Similarly, Carlson could be deeply critical of America—but always reaffirmed that he was an American by choice and loved his country. In the 1940s, he again became involved with a series of battles between the government and the makers of snake-oil nostrums. He detested “enriched” bread, which he thought added back only a fraction of the nutrients stripped to make white flour in the first place. Having seen the horrors of World War I, he was a peace advocate. He was called before the House Un-American Committee and the Senate committee investigating communism in higher education, and blasted both as un-transparent and un-American. He stood up for doctors drafted into the Army because they refused to sign loyalty oaths.

Carlson kept busy with his many investigations—mostly clinical by this point, as opposed to laboratory—in the years after his mandatory retirement at age 65. (Indeed, one of his causes was pointing out the absurdity of forcing retirement to people at that age.) He claimed to work 18 hours per days until 1952, when a heart attack made him cut back. He gave numerous lectures, wrote two books and over 250 scientific articles.

One of his causes that stands out against the background of Forteanism is his devotion to Humanism. As Humanism developed in America during the late 1920s and 1930s, it was not initially completely secular nor skeptical in the sense of the modern skeptical movement, which tries to debunk pseudoscience: in fact, one part of the humanist movement was worried over science and technology’s creation of deadly weapons. To be sure, the original Humanist Manifesto of 1933 insisted that life originated through organic evolution and ruled out the need for supernatural forces, but the membership was more eclectic than the manifesto allowed, and at least some of the founders were seekers of one sort or another. The movement was also anti-capitalist, though not communist.

Carlson was one of the signatories of the original manifesto, and many of his speeches extolled the importance of creative activity—and work. (He explained his own longevity as 3W-3D: Work, Work, Word, Diaper Days to Death.) Previous to that, he presented “The William Vaughn Moody” lecture at the University of Chicago on “Science and the Supernatural,” subsequently published in the journal “Science.” It showed him to be no friend of religion, and also aware of science’s limits: science approximates the truth as best as any human production can, dependent upon a method of controlling variables and investigator honesty. Religion, on the contrary, is made up of revelations that are often erroneous and offer no testable forms of knowledge. At best, scientists can ignore religion as a series of statements of no particular interest. At worst, they have to fight against religion as something that stands against the development of knowledge. The persistence of religion to this day, Carlson suspects, is a relic: all humans, all human societies, go through a religious phase. But it is a childish thing, and should be set aside when one is no longer a child.

Anton J. Carlson died 2 September 1956 of cancer. He was 81.

So what can we say of Carlson as a Fortean? It is unclear how Carlson ever came to Charles Fort’s books, if he read them at all. The (relatively) small Humanist community did overlap the (even smaller) Fortean community, but the connections I can document don’t come until the mid to late 1940s. The earliest is from 1944, which is a couple of years before Ajax joined, making it possible that he heard of Fort through this rout. More likely, Thayer approached him: Carlson was publicly known (featured on a 1941 cover of “Time” magazine) and Thayer recognized some of the affinities between the Humanist movement and Forteanism, even if he did not always appreciate the Humanists and their allies. Nothing in the pages of Doubt make me think that Carlson was a partisan of Fort, and I have seen no references to Fort in his own writing. Certainly, Fort’s empiricism might have intrigued him; likely his theories—speculative although they were—would have turned him off.

Thayer was excited to announce Carlson’s joining the Society in March 1948—it was that double-edged sword of Forteanism (and other fringe groups): disparaging science, but then trumpeting when recognized by science or scientists. The same thing had happened earlier when Dr. Frederick S. Hammett joined. They made the announcement in the midst of a column documenting the Society’s recent successes: “And--to top all--Dr. Anton J. Carlson, professor emeritus of U of Chicago, ex president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, joined the Fortean Society on the democratic level of corresponding membership--just like an ordinary mortal . . . Can anyone doubt our manifest destiny?.” (Thayer made similar noises in Doubt 41, July 1953, touting Carlson’s membership as more proof of the Societies strides.)

In that initial announcement, Thayer continued, “Our new Carlson sends a small basket of pamphlets--reprints of his lectures and articles. They display as pure a Forteanism as Fort himself possessed--roughly, the percentage figure made so well known by the ads for Ivory Soap. ... On 12-29-47 old style, the Dr. busted into the papers by telling the AA for the AS that white bread contained ‘nerve poison.’ Clearly he is not in the pay of the bread trust, nor an intimate of Truman’s physician.” Thayer and Eric Frank Russell—among others—were keenly skeptical of industrialized food, especially bread. (Henry Miller rote an entire essay decrying the horrors of American bread compared to what he could find in France.) And so on that point alone, Carlson was a welcome voice. A year later, Thayer wrote to Russell repeating Carlson’s warnings, and admitting that he himself only ate rye bread, so afraid was he off what was the the new staff of life. Thayer made the association, again, between bread and Carlson at Russell’s prompting in issue 33 (October 1951): after Russell complained about the poor quality of food available in post-War England, Thayer advised readers, “Ask your local Health Officer, family doctor, or MFS ‘Ajax’ Carlson how flour is bleached and processed in America!”

Of the may recurrences of the name “Carlson” in Doubt during subsequent years, only Four of them can be definitely attributed to Ajax. The first was a passing mention in the context of some Chicago Forteans possibly organizing themselves into a chapter. Thayer thought the potential explosive, among other reasons because on Chicago Fortean was against vaccinations and Ajax was for vivisection—the use of animals in experiments—a cause that Thayer himself championed against. That was in Doubt 24 (April 1949), and clearly reflected Thayer’s fantasies more than the reality that Carlson might have entertained the notion of meeting with other Forteans. (In fact, there is no evidence that the Chapter ever met.) The second mention was of another reprint being offered for sale. Doubt 30 (October 1950) relayed, “MFS ‘Ajax’ Carlson, former president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, has donated to the Society a few copies of a pamphlet, a reprint of his essay on Science, Education, and the Future of Man. While they last--25 cents each.

The other two mentions are more substantive, bookends of a sort: though also launchpad for a mystery. Frederick Hammett died in 1953, and Thayer told Russell that Ajax had agreed to replace him as an Honorary Founder of the Fortean Society (filling the seat originally held by Booth Tarkington). There’s a suggestion that Thayer was still genuinely proud of this connection: he bragged to Russell that Doubt 41 (July 1953), the issue with the announcement of Ajax’s elevation, was the best ish ever, to my way of thinking. Meaty as the southwest corner of a hog.” And the announcement was as full-throated as his initial acceptance of Carlson into the Fortean fold: Hammett had been “the living bridge between Forteanism and capital ’S’ Science, our foot-in-the-door of Orthodoxy” and Carlson was a perfect replacement: “Now that he has the blessing of the Damned as well, he is indeed a complete man.”

Only three years later, though, Carlson himself would pass, without his name ever having appeared in Doubt until his obituary, which was the first to sound the note of Thayer’s disappointment. From Doubt 53 (February 1957): “Then we lost out newest Honorary Founder, the celebrated ‘Ajax’ Carlson of Chicago. It would be quite useless for us to recap the career of Dr. Carlson. The Scientific press has done that ad nauseum. For a few of his honors see DOUBT #41. Unfortunately Dr. Carlson did not live up to our expectations of him after accepting the post of Honorary Founder but we lack the space to go into detail. Our problem now is to find a successor operating within the Sacred Circles of Science. Suggestions are solicited and our progress will be reported.”

And there is the mystery. What were Thayer’s expectations, and how did Carlson fail to meet them? Certainly, there were differences in viewpoint between the two men, but much of that was long-standing, known to Thayer since accepting Carlson and (presumably) reading his reprints. Carlson was a vivisectionist, Thayer not. Carlson was patriotic, Thayer not. Carlson thought good science could at least approximate truth, Thayer did not. Did Thayer expect Carlson to give up these beliefs? That seems unlikely. And unlike Ben Hecht, whose public actions Thayer also did not like, Carlson does not seem to have done anything after 1953—when he became and Honorary Founder—as out of character as Hecht cheering on the foundation of Israel. He continued to complain about the poor quality of American food—dog’s eat better, he said—and blamed it for the growth of obesity (1 in 5 Americans was overweight), the prevalence of so much food in such variety making people fat. He worried over alcoholism, but was not a prohibitionist, recommending a glass of alcohol a day and noting he was a moderate imbiber. (Two glasses was a waste, three caused poisoning.) These might have irritated Thayer slightly, but they were of a piece with what Carlson had been saying for years. And Thayer himself followed Carlson’s 3W-3D recommendations, even if he didn’t credit Ajax, working hours on end every day.

It is possible that Carlson’s connection with the Humanist movement grated on Thayer. In 1953, Carlson was named the first ever Humanist of the Year, by the American Humanist Association (whose magazine, the Humanist, was run by Edwin H. Wilson, a Fortean). That same year, The Humanist published a symposium on the Humanist Manifesto at 20, with recommendations for changes. Carlson recommended that point 14 be altered, as it reeked too much of the Great Depression and was not so relevant anymore. It’s possible Thayer heard about this suggestion and objected, since he was no fan of the capitalist system that point 14 attacked, but all of that seems a little too picayune. The point read: “FOURTEENTH: The humanists are firmly convinced that existing acquisitive and profit-motivated society has shown itself to be inadequate and that a radical change in methods, controls, and motives must be instituted. A socialized and cooperative economic order must be established to the end that the equitable distribution of the means of life be possible. The goal of humanism is a free and universal society in which people voluntarily and intelligently cooperate for the common good. Humanists demand a shared life in a shared world.” He also thought the document should stress the social responsibility of the individual more than it had—which would be in line with his own activities but also would have gone against the grain of Thayer’s more individualistic, voluntaristic ethos.

The best explanation I can come up with, and it’s not a great one, is that Thayer was disappointed that Carlson did not point out the shortcomings of science as much as he would have liked. Hammett had, and had even cited Fort in some of his papers. Carlson seemed (based on my superficial reading of the record) to have become more accepting of science, less likely to equivocate, and more dismissive of scientific ignoramuses, the number of whom he thought was growing. An obituary quoted him saying,” “The great mass of people of our age, even in the most enlightened countries, in their thinking and their motivation, are nearly as untouched by the spirit of science and as innocent of the understanding of science, as was Peking man.” That’s the kind of scientific triumphalism that would set Thayer’s teeth on edge. The problem with this hypothesis is that the quotation can be traced back to 1938, at least. So was the problem just that Thayer wanted Carlson to change, but the scientist refused?