Barley was a big player in the modern astrological movement, but almost all of the biographical material on him comes from Thayer’s obituary—which information was, in turn, provided by Barley’s widow. According to that source, he was born 7 February 1872 in Stoke Newington, London, to Hildyard and Emma Barley. He attended a Dame School until age six—just after England passed its compulsory education law, which made Dame Schools less prominent—and then his family moved to Ramsgate, Kent. Hildyard was a Wesleyan preacher and Alfred boarded at a Wesleyan school in Yorkshire until he was fifteen. He then moved to Stuttgart for a year, where he studied music. At some point, he also took a degree in Pharmacy, but in his early years he was moved by music. Some of his original compositions were played in the early years of the twentieth century—at a time when Alfred would have been just into his thirties. [“Alfred Henry Barley” The Fortean Society Magazine 6 (Jan. 1942): 4-5]

In his early years, Barley had been an agnostic, despite his upbringing (or maybe because of it), then drifted to spiritualism. During the same years he was composing music [Alfred H. Barley, Children’s Album for the Pianoforte, London: C. Vincent 1901; The Strad, Vol 14, no 158, June 1903, 326] he also began to write on astronomy with Alan Leo [AHB and Alan Leo, The Rationale of Astrology London” Modern Astrology, 1905]. Leo (his real name was William Frederick Allan) is credited with bringing astrology back into vogue at the end of the nineteenth century (it had seen its fortunes fall since the 17th century) and recasting it in modern forms: no longer would astrologists focus on predicting events but rather analyze a client’s character and point out areas of potential stress and harmony. He launched The Astrologer’s Magazine (later renamed Modern Astrology) in 1889 with Frederick Lacey. Barley apprenticed himself to Leo and became a sub-editor of Modern Astrology [James H. Holden, A History of Horoscopic Astrology, Tempe, AZ: American Federation of Astrology, 2006, 207; Patrick Curry, Confusion of Prophets: Victorian and Edwardian Astrology, London: Collins & Brown, 1992, 149].

In 1910, Barley married Annie Lewton of Wells, Norfolk, England. Probably under the influence of Leo, Barley had become a Theosophist, and Annie, too, was interested in theosophy. But, as Thayer delicately put it, they appeared “to have been associated with the Theosophical Society at a time of schism.” The schism in this case was brought on by Annie Bessant and Charles Webster Leadbeater; Bessant was the president of the Theosophical Society from 1907 to 1933 and Leadbeater an important Theosophical writer. Together, they moved the Society away from its founder, H. P. Blavatsky, highlighting their own interpretations, merging in Catholicism, and focusing on the practice of psychic and occult powers, and introducing a boy who they believed would be Theosophy’s Christ. Old-school adherents were upset by these changes [James A. Santucci, The Aquarian Foundation Communal Societies, 9 (1989): 39-61, pp. 43-44;].

Barley suffered conjoined crises in 1917. Leo, his mentor, was found guilty of giving pretend fortunes and, a few weeks later, died of apoplexy [Annie Besant and Bessie Leo The Life and Work of Alan Leo, Theosophist, Astrologer, Mason. London: Modern Astrology Office, 1919, 105]. Barley was elevated to full editor of Modern Astrology, but gave up that job within months, writing, "I have decided, after full consideration, to sever entirely my connection with the business enterprise known as "Modern Astrology" Office on and from the first of January.” [Modern Astrology, January 1918, p. 1] That same year, fed up with the Theosophical schism, he and Annie resigned from the Society.

In Thayer’s account, the next event of consequence was that the Barleys moved to Canada, and then to the State of Washington. However, that glosses over one of the more interesting episodes in Alfred’s life. In 1926, he and Annie met the man who they hoped would repair the Theosophical Society’s vision: Brother Twelve. So enthralled were they that they gave to him all their earthly belongings and followed him halfway around the planet. Only to be disrespected and abused.

In the spring of 1926 came to Southampton Brother Twelve. Born Edward Arthur Wilson, Brother Twelve emphasized the need to reclaim Blavatsky’s original Theosophical teachings—but also the need to do so by going forward, not back. He saw the coming of a new age, the Age of Aquarius, when Blavatsky’s Universal Brotherhood would be achieved. And he said he and his followers would be the seeds, the fruition of the movement not coming until 1975, 100 years after Blavatsky’s original announcement and seventy-five years after his own reformation. About a dozen rich and socially prominent followed Brother Twelve to Vancouver Island, where they were would spur on humanity’s evolution into what Blavatasky had called the Sixth Root Race. The Barleys were among these pioneers, having turned all their belongings into cash, which they donated to the cause.

In British Columbia, though, Brother Twelve became increasingly erratic. He encouraged his followers to be suspicious of each others’ motives, and to depend only upon him. He brought in two different paramours, the first suffering a mental breakdown after she failed to give birth to the New World teacher, and the second cruel and abusive, driving one congregant to attempt suicide. A few leaders took exception and sued Brother Twelve, which came to nothing. In 1933, Brother Twelve and his love Madame Zee left on an eleven month trip to England, appointing Alfred Barley business agent in charge of the colony. When they returned, the abuse did, too; apparently finally being fed up, the Barleys and a few others dissented, only to be banished. Destitute, the ostracized sued the Brother Twelve—and this time won. The Barleys were awarded a return of the $14,000 they had donated as well as the land itself, since Barley was still listed as business agent. It wasn’t worth much. Brother Twelve paid nothing, and he and Madame Zee destroyed the camp, destroying the furniture, buildings, and one of the yachts. They absconded in the other, with a vast amount of money they had received from long-distant postulants. [James A. Santucci, The Aquarian Foundation Communal Societies, 9 (1989): 39-61.]

So, in 1934, they left Canada for the States. According to the census, they were in Oceano, California, in 1935—in all likelihood, they were drawn here by Halcyon, a Theosophical community established in 1898. [Robert V. Hine, California’s Utopian Colonies. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1953, 54–57.] By 1940, they were in Getchell, Washington (near Everett), where they owned a berry farm. How they got the funds to purchase the land is unknown—perhaps by selling off their Canadian property. They were not citizens. The work had to be hard—Alfred was 68 and Annie 73; both worked over forty hours per week, every week of the year. They did have three farm hands, though, so they must have made some money.

And Barley had time to indulge his interests. In 1937, the year of the first Fortean Society Magazine, he joined the Society. According to Thayer, he wanted to be put in contact with someone who had formally studied astronomy but had not yet accepted all of its facts as true. He wanted to spread word of the Drayson Problem. Barley had come across the Drayson Problem in the course of his astrological research and, according to his wife, sought at first to prove the whole problem correct. But instead he had changed his mind. Now, he was hoping to find from the Fortean Society an apprentice, someone who would carry on study of the problem.

The eponymic Drayson was Major General Alfred Wilks Drayson, a polymathic and eccentric Victorian gentleman. He had gotten Sir Conan Doyle hooked on spiritualism, for instance, and was so often visited by spirits and apports—teleported items, in this case produce and eggs from New York—that he rarely shopped, he said. [Daniel Stashower, Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle, Ny: Macmillan, 95-96]. Trained at Greenwhich Observatory, he was teaching astronomy to cadets at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich around 1870 when a student seemed to find a fundamental anomaly in astronomical theory.

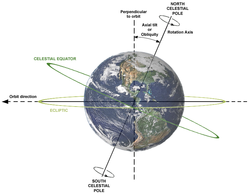

The Earth’s motion through the heavens can be described in different ways, giving rise to different definitions of the equator or the poles. The celestial pole is where the earth’s axis of rotation intersects the celestial sphere—that is, the (imaginary) rotating sphere of stars. The earth’s ecliptic pole, by contrast, is at the intersection of the celestial sphere and the line perpendicular to the ecliptic plane (the path traveled by the Earth around the sun.) The distance between these points is the earth’s tilt, or obliquity. It had been known for some time that this obliquity changed over time, becoming ever so smaller. [Joscelyn Godwin, Arktos: The Polar Myth in Science, Symbolism, and Nazi Survival Kempton, Il: Adventures Unlimited Press, 1996, 206-7]. Barley reported the following conversation:

The cadet asks if the distance between the celestial pole and the ecliptic pole had always been the same.

Drayson: “No. It was formerly somewhat greater, and it is subjected to an annual diminution of about a half second, which is termed the Decrease in the Obliquity of the Ecliptic.”

Cadet: “Did you not say just now that the precession of the equinoxes was caused by the [celestial pole] moving in a circle round the Pole of the Ecliptic?”

Drayson: “So it is.”

Cadet: “Then what is the centre of that circle?”

Drayson: “The centre? I told you, the Pole of the Ecliptic.”

“But you have just told us that the [celestial pole] is decreasing its distance from the Pole of the Ecliptic. How, then, can this be the centre of the circle in which the [celestial pole] is moving?”

Stumped, Drayson looked into the problem further, and saw that no one else, either, had noticed this contradiction. Study led him to discover that the center was actually six degrees from the ecliptic pole, and that the celestial pole described a circle about this point, completing a revolution every 32,000 years [Praising Alfred H. Barley, The Fortean Society Magazine, 5 (October 1941): 10-11].

Seemingly a mathematical error, fixed by insight and diligence, Drayson’s answer had a number of important consequences. If Drayson’s conclusion is accepted, then the so-called proper motion of the stars is not as thought—clearly important for an astrologer. But earth’s history is changed, too, with ice ages resulting from the tilt int he earth’s axis. As Barley would note, the warming of the summers over the last 2,000 year was likely due to this tilt. Drayson found some proponents for his theories, people willing to continue the work, but his ideas fell out of favor after a time, until resurrected by Barley.

Thayer was ecstatic to learn about The Drayson Problem. Here was an error in scientific thought that had persisted for centuries. And not just science in general, but his (and Fort’s) bugaboo—astronomy. It was a problem any smart child could see—and one had seen it—but most didn’t because they were so enthralled by authority and textbooks they never actually looked at the black sky of the night, never actually thought.

Thayer first mentioned Barley in that January 1940 issue, saying only that he had contributed material—which was probably related to Drayson. The next mention didn’t come until issue 5, in October of 1941, by which point Drayson was no more. He died in May 1940, only three years a Fortean. But he had made an impression on Thayer, who, as he had with Isaac Newton Vail, took up the mantle of (skeptical) crusader:

“This notice might be in the nature of a memorial—for Alfred H. Barley is dead. But instead of writing a memorial to one of the most valued Forteans of all the Society pledges itself to continue the work to which he devoted most of his life. The Fortean Society is a living memorial, a working memorial to all sponsors of the minority viewpoint, to all who raise their voices in dissent.

“Older members may recall the Society’s search for a young astronomer who had learned his trade without falling completely under the spell of the Schools. Such a youth was being sought by Alfred H. Barley, author of The Drayson Problem.”

Thayer followed up with another piece in the following issue, number 6, dated January 1942:

“The Fortean Society inherited the obligation and the privilege of carrying the work forward. This work—in the case of the Drayson Problem—consists of bringing this fault in their figures to the attention of the younger generation of astronomers in such a way that the importance of the matter can no longer be ignored. Correspondence to that end is already in progress and the results will be duly recorded here.”

That issue of The Fortean Society Magazine also carried “Circus Day is Over,” which caused Thayer no end of headaches, but he still made good on his promise. In September 1942 he asked one ofSociety member to see if Barley’s volume on Drayson was at the Naval Observatory, along with any related books on the same topic [Don Bloch papers, New York Public Library]. When he learned that the book wasn’t there, he tried to get Barley’s The Drayson Problem on its shelves. A few years later, and he was still at the task. In 1944, he wrote

“A third Honorary Member who entrusted the Society with a definite obligation was the widow of Alfred Henry Barley, the protagonist in this country of the renegade astronomer, Alfred Wilks Drayson. Our first effort has been to make the Drayson Problem available to students, most of whom had never dreamed such a problem existed. Next, we attempted to check libraries and observatories to which Mr. Barley had sent books on the subject, to learn if these books were catalogued and available. To date not a single copy outside of the Library of Congress has been discovered.

Special thanks are due to Mrs. R.W. Herrick, M.F.S., of Newman Center, Mass., and to her husband, who pursued the search throughout the State of Massachusetts—with only regrets from librarians. In every instance where the sought-for book was missing the Society offered to supply a new copy gratis. Several institutions accepted this offer. Members are urged to check the local libraries for any books by Drayson, and report to the Secretary.

Other members who aided in the search in other States were John Davenport Crehore, nephew of the physicist, Don Bloch, Ross M. Colvin and Vincent Ford . . . At the Flower Observatory, Upper Darby, Pa., where the High Priest in charge was the venerable Charles P. Olivier, who puts ‘Come to Jesus’ stickers on his outgoing mail, Mr. Ford found no Drayson on the shelves, but Mr. Olivier had heard of him. ‘Oh, yes, Drayson,’ said the Professor, ‘he was crazy.’” [“New Life Member,” The Fortean Society Magazine 9 (Spring 1944): 2.]

Thayer also endeavored to get into contact with Lt. Colonel T.C. Skinner, who was an advocate of Drayson’s living in England. The war made correspondence across the Atlantic difficult, though, and it is not clear how much contact they had []. Skinner had a different view of Drayson, anyway, using his ideas to augment Creationist arguments in support of a Noachian flood [Ronald L. Numbers The Creationists, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993, 150, 390; T.C. Skinner, The Ice Age : Its Astronomical Cause, and the Bearing of Drayson's Discovery on the Biblical Account of the Deluge (with Illustrations), Journal of the Transactions of the Victoria Institute 61 (1929): 118-141]. By 1948, he had lost contact, asking Eric Frank Russell, his friend in England, to find out what had happened to Skinner—he had died two years before—and seemed more curious than ready to resume any correspondence, since Thayer told Russell to not let Skinner know Thayer was asking about him.

And when Thayer started imagining a Fortean University (unsubtly abbreviated F.U.), he wanted Drayson in the curriculum, listing his problem as the second major area of study, after Fort. By this point, Annie Barley had donated books as well as (some of?) her late husband’s papers to Thayer and the Society, and Thayer thought these would be good material for study. He thought a course of study in Drayson would “inform the student of a basic impossibility in received and currently ascendant astronomical theory.” But a chair in the field, he said—and one must imagine his tongue in his cheek here—would only go to a person who had graduated college with a degree in astronomy, someone familiar with the Drayson problem, with Fort’s writings, and a member of the Society—who could, oh by the way, post a $50,000 bond for the preservation of Barley’s papers.

As enthusiastic as he was about the Drayson problem, Thayer was not a convert. Drayson had not provided a new theory, or a new fact—but only a problem: an area of work. And Thayer was not about to subscribe to any particular interpretation of natural phenomena. After seeing Thayer’s proposed F.U. a member, Alexander Grant, wrote,

“May I suggest that the Fortean University Chair of Drayson get together with the flat-earth boys--ditto Cahill supporters? It seems that there is a fundamental contradiction somewhere. Also Graydon and Crehore.”

Thayer responded,

“Indeed there would be ‘fundamental’ contradictions galore in teaching these subjects as most subjects are taught in more orthodox universities. F U does not teach, it studies. Each Chair stands on its own four (or more or less) figurative legs, merely as a field for investigation and further development. No subject is taught as true by F U. Each is advanced as a question profitable to explore. Thus no contradiction exists.”