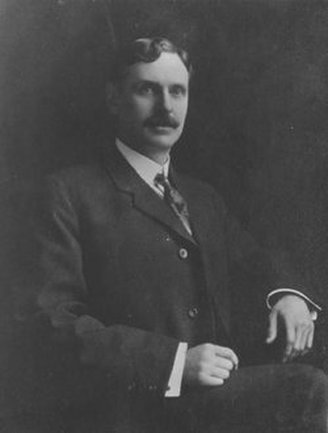

Albert Cushing Crehore belonged to the same generation as Charles Fort. He was born 8 June 1868 in Cleveland, Ohio to John and Lucy Crehore (née Williams). They had met when Lucy was a student in John’s high school class. The family was well-off, John—who had come from New Hampshire, and whose line could be traced back in America to 1640—owned property worth $15,000 in 1870 and Lucy—born in Ohio—was worth $10,000. Albert was the third of four children; in addition, the four others lived with the family, including two who were likely family members; all but one of those four worked as domestic servants, the sole exception being a woman in her 80s. His father passed when he was sixteen years old. During high school, Cushing decided to follow his father in the sciences. There is no extant census for 1890, but we do know that Crehore graduated from Yale University in that year, further testifying to the family’s wealth. Degree in hand, Cushing then went on to Johns Hopkins, where he studied electrical engineering for a year.

In 1893, Crehore accepted a position at Dartmouth University and began what he called the second phase of his life, Inventions. (The first was everything that came before and was prepatory.) He also began his own family during this period, marrying Sara Buck 10 July 1894. She was the cousin of a Yale Glee Club friend (and daughter of a reverend). It so happens, too, that both families were connected to famous doctors, Sara’s to William Osler, Crehore’s to Harvey Cushing. The following year, Sara gave birth to Dorothy Dartmouth Crehore, the first of four daughters born over the next 11 years. Cushing was making $1,500 per year at the time. And it was around this time that he came back into contact with George Owen Squire, whom he had known at Johns Hopkins, and who would be an important collaborator on his inventions. There were lots of circles being completed here: Cushing’s father, John Davenport, had graduated from Dartmouth in 1854.

I don’t want to pretend that I understand what Crehore was working on in any more than a rudimentary way, and the plain fact of the matter is that the details are of no real moment for understanding him as a Fortean. He was working in a well-developed electromagnetic tradition, and also innovating that tradition and cashing in. Along with Squire, he invented instruments for measuring ranges and studying high-speed projectiles—research that led to their patenting of the Polarizing Photo-Chronograph, a device that measured short time intervals, in 1897. The research took them from Cleveland to Virginia to England. They also studied long-distance telegraphy and established the Crehore-Squier Intelligence Transmission Company, but had a substantial falling out over the funding; Crehore said he lost a lot of money, especially painful since he had resigned from Dartmouth. As it turned out, the basis for the telegraphy business was wrong, anyway, though that was impossible to know at the time.

Returned from Europe, Crehore continued to invent, building a laboratory in New York. (He first worked in Tarrytown, before moving to Yonkers—the latter where he and Sara were in both the 1905 and 1915 New York State censuses.) He had been supplementing his income with patents even while working with Squier, selling some on electrical trains to G.E., for example. He filled telegraph contracts for the government, too. He published a book on telegraphy in 1905. Other patents were sold to AT&T. Crehore was also involved with the invention of the micrograph, which was used to measure the activity of the heart, as well as an early version of the teletype machine. He continued through this phase of his career for five or six years after the publication of his book. At the time he was well known and well compensated for being able to understand and manipulate natural laws according to an electromagnetic understanding of physics: his ideas had real world consequences.

Crehore would later say that around 1911, he turned his attention from invention to atomic theory, initiating the third phase of his life. Herein lay the basis for future connections with the Fortean Society and other groups promoting alternative forms of science. Crehore’s understanding of the atom was rooted in the work of physicist J. J. Thomson, who, early in his career, had advocated the Vortex Atom, which became the favorite of Albert E. Page and other scientific dissenters. Thomson revised his theories, and discovered electrons, using the cathode tube invented by the physicist William Crookes, who was also a supporter of parapsychology and a dabbler in alchemy.

Again, I don’t want to overstate my understanding of Crehore’s theories. Unlike many other Forteans, he gets deep into the weeds of atomic theory, using—and comprehending—complex mathematical models. The point is that he developed an electromagnetic theory of the atom at odds with the Quantum atom being developed by Niels Bohr—even if he did borrow from some of the work that Bohr did. Crehore was particularly exercised that Bohr’s theories were at odds with fundamental assumptions of electromagnetism. By the early 1920s, Crehore had developed an alternative model of the atom to his satisfaction.

There were some major changes that correlated with the ending of this, the third period of his life. His brother—who had funded and supported his laboratory—took sick and moved to California for his health; he died there in 1918. Meanwhile, his own theoretical work was going unappreciated—he found outlets for publication, some of the same, in fact, that printed Bohr’s papers, and gave talks to scientists, but the mainstream of physics research was on the Bohr atom and what became Quantum Dynamics. So, he sold off his laboratory supplies, trying to recuperate the monetary losses he had suffered since quitting inventing. Sometime during this period (after 1915, before 1920) he seems to have separated from his family, and perhaps married again, briefly. Sara and the girls were living with Sara’s mother according to the 1920 and 1930 census (and a much later article said that Sara had moved back to New York after Crehore’s ‘death,’ which suggests a euphemism for their separation). But Crehore moved to Denver—the 1920 census records him there—and worked at the University of Denver. The census also recorded a “Mrs. Albert Crehore” from Rhode Island living with him. In Colorado, Crehore equipped a small basement shop and went back to tinkering, selling some of his inventions to the government. He also published a book, The Atom, which presented his model of it. Cherri only spent a year in Denver before returning to New York, short a short stint. A former student of his at Cornell put him in contact with G.E. and Crehore took a job with the company in his hometown, Cleveland. It was there he published a paper that he thought worked all the kinks out of his atomic theory. As far as I can tell, he spent the rest of his long life in Cleveland, some of that time living with his mother (who passed in 1930), but otherwise, according to the City Directory, with no one else.

From his perch in Cleveland, Crehore spent years assaulting the coalescing quantum theory of the atom—and offering an electromagnetic alternative. He published a number of books: The Progress of Atomic Theory (1926); What the Neutron Is (1941); Atomic Theory (1942); The Crehore Atom (1943); Electrons, Atoms, Molecules (1946); A New Electrodynamics (1950); The All Nuclear Atom (1951); Spiral Families (1953); The Universal Distance: What Causes It? (1956). (I don’t know why there was a big gap from the mid-1920s to the 1940s.) In 1944, he self-published an autobiography, a good half of which was pens justifying his theories. For the most part—and as far as I can tell—there was not a great deal of development in his ideas during these final thirty-five years or so, but rather an elaboration of the ideas he had already convinced himself of: that in their stable states, atoms do not have electrons orbiting about a nucleus; rather electrons are part of the nucleus. Crehore’s theory was used to develop and re-explain the periodic table. It also gave rise to an explanation of gravity—by positive charges rotating in the nucleus—making it an an early example of the so-called Theory of Everything, uniting the fundamental forces of physics. One thinks of the way believers in the Ptolemaic universe continued to invent more and more epicycles to account for better observations, until the Copernican theory just became simpler. Cherri could continue to develop his theories to account for experiments, but Quantum theory just became simpler.

Crehore was hard to classify for the rest of the world; a conservative physicist in the tradition of Sir Oliver Lodge (another proponent of spiritualism, by the way), he could be increasingly ignored by Bohr and Einstein and other advocates of the Quantum Electronic atom as more and more experiments supported their conceptions (even as they disagreed among themselves). The seminal skeptic Martin Gardner noted that many physicists considered Crehore’s ideas worthless, but he himself was unwilling to totally dismiss them, given Crehore’s impeccable resume. Those exact traits—respectable history, but dissenting—made Crehore attractive to theorists farther on the fringe. In the 1940s, apparently, he had some correspondence with Richard Shaver, purveyor of the so-called Shaver mystery, which claimed an alternate history of the world, invented a universal alphabet, and insisted there were detrimental robots living in the hollow earth using rays to cause misfortune among humans. The stories sparked by Shaver’s thoughts—which he insisted were factual—became a sensation in science fiction circles during the late 1940s. According to Shaver’s biographer, Shaver had approached Crehore because his ideas on gravitation could be used to support the supposition of anti-gravity drive for spaceships and because Crehore had thoughts on extending the human life-span: a Fortean topic for sure, but I know nothing of Crehore’s interest in that matter. The Fortean N. Meade Layne also cited Crehore’s model in support of his etheric physics and explanation for flying saucers.

Crehore died in Cleveland on 15 January 1959, aged 90.

I have found no evidence that Crehore himself read or cited Fort. Indeed, even if he did read Fort, it is unlikely he would have found him supportive, since Fort’s criticisms of quantum theory were mild compared to his attacks on astronomy. Crehore seems to have taken himself far too seriously to find Fort’s humor appealing. He was out to establish science on a firm nineteenth-century foundation, not to undermine the very notion of knowledge. His critiques of science were narrow and focused on one tradition which he thought had made a wrong turn and needed to be corrected.

But Crehore was interesting to Forteans—as he was to Shaver and Layne—because he offered an alternative science even while having excellent credentials: he finessed the problem that bedeviled Forteans, that they wanted the respect of science even as they sought to undermine the scientific endeavor. There was hope he might be like Frederick Hammond, the irascible biologist and Fortean. As far as I can tell, though, Crehore was only weakly connected to the Fortean Society, if at all, although he was alive for almost its entire existence. Thayer, though, found in the atomic model two (contradictory) reasons for promoting Crehore.

Thayer featured Crehore early on, selling his “Atomic Theory” from early in the 1940s. And he devoted a fair amount of space to discussions of the atom in issues 7 and 9, which may have been a response to the irritation he caused with issue 6: the subsequent issues were much less political, often devoted to an obscure book on India, Thayer apparently gauging what he could get away with. Crehore probably seemed safe, as his was a fight within science and promoting his theories what not overtly political—at least at first. Thayer explained in issue 7 why he had been spending time on this dissenting model of the atom:

“Forteans have been asking if the Society has sold out to the physicists’ union, because the big push we’ve been giving ATOMIC THEORY by Albert Cushing Crehore, Ph.D. . . . . . Not so . . . As a matter of fact, degrees can be deceiving, and Dr. Drehore is not a member of their union. He is rather, to the physicists, as poison ivy is to a Boy Scout. (That is to say—they won’t touch him.)

He gave the world his atom in 1921. The god union members went right on with what they were doing. In 1926, he amplified his ideas in a larger book which nobody in the Sacred Circle has taken the time to read—nobody, that is, except H.A. Lorentz, who read it and died. Before he died, he wrote Crehore a 28-page letter, which may be the most important unpublished Lorentz document in existence. The letter is said to praise most of Crehore’s work, and to reveal basic misunderstanding of the points to which it takes exception.

Crehore answered Lorentz, explaining the misunderstood points—mostly mathematical—but before the letter could be delivered Lorentz was dead. Whereupon Crehore offered the correspondence to publications which should have been interested but they declined to publish it. Since then, Physicist Crehore has been on the union’s leper list.

To most Forteans who have examined Dr. Crehore’s new, simplified text (which we are pushing) the mater appears to be no more than the same old black magic that keeps Millikan and Einstein in pin money, although the contention is that it links up Newton and Max Planck, and truly explains ‘gravitation.’ We wouldn’t know. Nevertheless the Society champions the outcast, on the theory that no physicist’s preposterousness is any sillier than another’s, and that Crehore is entitled to have his name engraved on appeals for funds to save delinquent youth, just like any other ‘leader of American thought.’

To be sure, Crehore himself would prefer ‘recognition’ from his colleagues, but he does not appear to realize that such ‘recognition’ is not based upon the merit of an individual’s performance, but comes from political, philanthropic or some other commercial connection. The Society’s recommendation to the author is that he either (A) make pals with a Carnegie, Du Pont or some war millionaire who will endow an institution for the prosecution of his researches, thus affording employment for a lot of the boys, or (B) think up some good boob-bumping dodge like Einstein’s ‘only twelve men understand me.’ We wish Dr. Crehore well, and accordingly warn him that his publicity stunt must be of higher calibre than Sir Hubert Wilkins’ submarine to the North Pole, Byrd’s ‘bus’ to the South Pole, or Auguste Picard’s to balloons to the ‘stratosphere.’ Let him take a tip from the politicians and make his hoax so enormous that everybody will swallow it.”

That last line walked up to the edge of sedition, suggesting as it did that the entire World War was a hoax—which Thayer said outright earlier—but the main focus was poking fun of science, and so kept Thayer on relatively safe ground.

Two issues later, Thayer’s magazine featured a page-and-a-half piece on the Crehore atom titled XVI. It was noted to have been “contributed,” with no other attribution, but reads as though it had been submitted by Crehore himself, which suggests that there had been some correspondence between Thayer and Crehore—Thayer was never shy about writing people he thought might be sympathetic to Fort or the Society named after him—and also that Crehore was reluctant to have his name too closely associated with the Society: after all, he was still aiming for respectable acknowledgment by physicists. The article continued, as well, keeping Thayer out of hot water politically. That Crehore’s theories were not particularly taken by Thayer to be true came across in issue 11, when Thayer discovered the maverick thinker George F. Gillette, whose ontology, he believed, included Crehore’s atomic theory while also transcending it: Crehore was more of an icon than a Fortean.

As time and the war continued, Thayer never did embrace Crehore fully, but he used him in a more political way, regaining his seditious edge. Doubt 13 (winter 1945) saw Thayer declaring the atomic bomb a hoax: “Now the biggest lie has been told. Now the greatest crime has been committed. Now the mental slavery of the human race is very nearly complete,” he wrote on what he called “the Semantic Bomb.” There couldn't be an atom bomb, he said, because there wasn’t an atom, but a multiplicity of them: “‘Atom?’ we ask. ‘Atom? Why, an atom is a postulate, a mathematical equation, a dream, an inference, a meal-ticket for the priesthood of Science, just as God is the meal-ticket for the priests of religion. Nobody has ever seen an ‘atom’ anymore than anybody has ever seen ‘God.’ Both notions are equally dependent upon faith. And in the laboratories you will find as many different definitions of what an atom is as there are different religions in the world. Whose ‘atom’ are they using in this ‘bomb? Dalton’s, Bohr’s, or Page’s or Crehores?’

“Since Crehore is a Fortean, we didn’t think he would sell Power his atoms to kill people with, and so it befell. As appears, it’s the Bohr version of the atomic myth, with modern improvements, that the free-prez is trying to sell us as ‘the greatest discovery since that of fire.’” Thayer continued his column, calling the story of the atom bomb a pernicious myth, one that allowed the powers-that-be to hoodwink the populace, making them belief in a figment of the imagination: that was the true crime, the mental slavery. All of which wasn’t to absolve the warmongers of actually killing millions with some kind of explosion.

And that last point came through again when Thayer was drawing up (specious) plans for a Fortean University. By this point, Thayer had accepted Crehore into the Fortean fold—he called him a Fortean in the above harangue—whether or not Crehore himself approved of this label. And he nominated Crehore to be the name of—and fill the—chair in the FU (his very subtle abbreviation for the Fortean University), teaching the Fortean equivalent of atomic physics. This was the 10th chair he imagined in his imaginary university (out of 13, of course), and he described it thusly:

“The Subject is theoretical atomics as presented by Albert Cushing Crehore, with emphasis on ‘the steady states.’ FU clings to Crehore because the author’s atom has never killed anybody. A statement of some of the differences between the Crehore atom and others (as printed in DOUBT #9) will be furnished free upon request.

The Chair of Crehore could hardly be fitted by anyone other than the author at present, but if any of the murderers who sold their honor and self-respect in the recent development of a new explosive now with to reform, their applications will be considered.”

This description came out in Doubt 20, a couple of years after Thayer’s attack on “The Semantic Bomb,” and by this point he was becoming tangled up by his multiple conspiracy theories. He continued to insist that the atomic bomb was likely a hoax, but nevertheless attacked atomic physicists—and their models—for building the tool that killed millions. Which was it, then? Was the atomic bomb atomic or not? Thayer didn’t really care—he was making a political point. His disinterest in the technical details came through a bit later, in Doubt 28, when a member of the Society objected that there were too many contradictions in the proposed Fortean University, with some subjects diametrically opposed to others. Thayer replied flippantly,

“Indeed there would be ‘fundamental’ contradictions galore in teaching these subjects as most subjects are taught in more orthodox universities. F U does not teach, it studies. Each Chair stands on its own four (or more or less) figurative legs, merely as a field for investigation and further development. No subject is taught as true by F U. Each is advanced as a question profitable to explore. Thus no contradiction exists.”

There is a suggestion that Crehore may not have been too happy about the political uses to which he was being put by Thayer. Nowhere did Thayer ever outright call Crehore a member of the Society (though he did call him a Fortean) but in the final (substantive) mention of Crehore’s activities, Thayer noted he was an ex-MFS: which suggests that if he had ever signed up to become a member, he had formally renounced that connection. (Thayer was loathe to throw people out of the Society, no matter their views, and no matter whether they paid, so any break was almost certainly initiated by Crehore himself.) That mention came in Doubt 31 (1951) and was accompanied by a very restrained endorsement of Crehore’s latest book, which might also suggest bad blood between the dissident physicist and the Society:

“The former MFS--Albert Cushing Crehore, Ph.D.--has written a new book--A NEW ELECTRODYNAMICS. Unless you know and admire Crehore’s atom, we hesitate to recommend the present extension of his work. He asks $5.00 for it. Address your orders to the author, care of V. E. Berner, 1199 Lader Road, Cleveland 24, Ohio.”

The Fortean icon no longer wanted to be used, and so was dropped from Doubt, although the Society and he would live for another eight years and both continue their respective quixotic jousting with mainstream powers. Nothing had changed—there was every reason that Thayer would have wanted to remain connected to Crehore—but Crehore was gunning for respectability, and that was something the Fortean Society definitively did not have on offer.