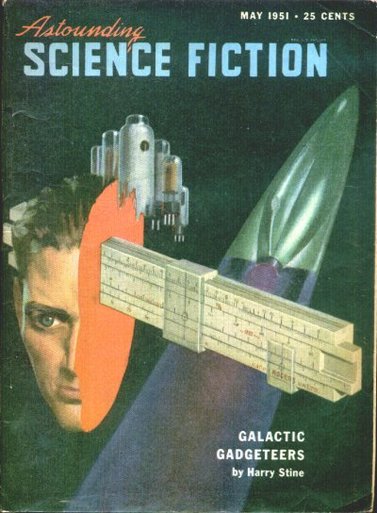

A letter from Wilson appeared in this issue of Astounding.

A letter from Wilson appeared in this issue of Astounding. To even the capaciously accepting Fortean Society, he was too outrageous—a fringe Fortean.

I know very little about Alan F. Wilson, and most of what I know comes from a remembrance. Aside from a few addresses he lived at, I have none of the usual biographical data, at least not in verifiable form. I do have a few purely speculative possibilities.

Wilson live in Cleveland, Ohio during the early 1950s, at least. Harlan Ellison, who knew him them, says he was in his thirties, but had already been married and divorced. Wilson worked for a factory—Ellison couldn’t remember which—and made a good living. Around about 1951, when Ellison was 17, Wilson hired him to be a go-fer: but one who also carried a gun. He made him deliver chemicals to different people (one case involved sodium, which Wilson later disposed of in a body of water, while Ellison watched, resulting in a huge explosion.) He had him woo a woman with a raw steak. He made him travel to another city and deliver the contents of a suitcase—the valise having been handcuffed to Ellison’s wrist—to fellow science fiction fan Don Ford.

Ellison wrote, much later: “Wilson looked like a Martian to me. At least, what I had always seen represented in sf magazines as a Martian: skinny, large head, receding hairline, big eyes. He was, to me, a weird and fascinating man.” There were signs he was very unusual—beyond, you know, hiring a 17-year old to carry a gun around Ohio and do errands. One task he gave Ellison was to, from time to time, scare him. “I didn’t ask him what he meant,” Ellison wrote. “I knew. He wanted me to feed his strangeness, whatever that was.” Thus, some nights the high school boy would climb up the outside of Wilson’s apartment and “make hideous sounds and tap on the window and scream and scare the hell out of him. Did he know it was me? Of course he knew. He’d asked me to do it, hadn’t he?”

I know very little about Alan F. Wilson, and most of what I know comes from a remembrance. Aside from a few addresses he lived at, I have none of the usual biographical data, at least not in verifiable form. I do have a few purely speculative possibilities.

Wilson live in Cleveland, Ohio during the early 1950s, at least. Harlan Ellison, who knew him them, says he was in his thirties, but had already been married and divorced. Wilson worked for a factory—Ellison couldn’t remember which—and made a good living. Around about 1951, when Ellison was 17, Wilson hired him to be a go-fer: but one who also carried a gun. He made him deliver chemicals to different people (one case involved sodium, which Wilson later disposed of in a body of water, while Ellison watched, resulting in a huge explosion.) He had him woo a woman with a raw steak. He made him travel to another city and deliver the contents of a suitcase—the valise having been handcuffed to Ellison’s wrist—to fellow science fiction fan Don Ford.

Ellison wrote, much later: “Wilson looked like a Martian to me. At least, what I had always seen represented in sf magazines as a Martian: skinny, large head, receding hairline, big eyes. He was, to me, a weird and fascinating man.” There were signs he was very unusual—beyond, you know, hiring a 17-year old to carry a gun around Ohio and do errands. One task he gave Ellison was to, from time to time, scare him. “I didn’t ask him what he meant,” Ellison wrote. “I knew. He wanted me to feed his strangeness, whatever that was.” Thus, some nights the high school boy would climb up the outside of Wilson’s apartment and “make hideous sounds and tap on the window and scream and scare the hell out of him. Did he know it was me? Of course he knew. He’d asked me to do it, hadn’t he?”

The two had met through the auspices of the Cleveland Science Fiction Society (The Terrans). Wilson had offered his apartment as a regular meeting place. The evidence suggests that Wilson was an active, if not remembered, fan. He knew fellow Fortean and science fiction Roy Lavender. He wrote in to magazines. He published the club’s effusions: “He had a Multilith machine right in the middle of the floor, a Varityper for typing up issues of the club newsletter.” Wilson also corresponded—sporadically, it seems—with more distant science fiction fans, including P. Schuyler Miller and Eric Frank Russell.

His ideas about the universe were deeply rooted in science fictional concepts. In early 1951, he wrote to Russell:

“I see the universe tentatively as network [sic] of teleport beams, some natural, some manufactured or engineered, some organic. The natural ones are geodesic or straight when unperturbed by ‘bodies’. Gravitic fields of passing star and/or planets catch the beams, pull them in, maintain a temporary contact, then snap away again. The beams often pass right into the core of the earth, and give rise to simultaneous seismic, atmospheric and polt[ergeist] phenomena at epochs of ‘contact’ and ‘break’. The rotating earth will seize a beam and twist it or ‘wind’ it about the earth until the tensions become so great that rupture must occur. At the points of entry and exit, the beam will be normal or nearly so to the earth’s surface, so that teleports will seem to be up-and-down and the appearing and disappearing points will seem to be stationary with respect to the earth’s surface for a time.

[new paragraph:] “Engineered teleport beams will be special engineered for minimum damage to planets and their life. Hence some of the gentle effects. Natural beams will boil up whole rows of volcanoes on occasion. The organic beams may partake of paternalistic vampirism, but you indicate that we are principally ignored. So long as we stay small and obscure. But it is death for nuclear powered trout. The sun grabs most of the teleport beams, but Earth picks up a few every day I think, and drops a similar number. All those that are momently [sic] grabbed by Luna are also grabbed by Earth, and all those that are grabbed by Earth are also grabbed by Helios. Canon Diablo.”

There are obvious connections between this conception of the universe and Shaverism, which Wilson does not deny. Later in the same letter, he called Shaver’s ideas “The tracing of ancient cosmic contacts.” There are also echoes of Russell’s writings, what with the psychic vampirism recalling his “Sinister Barrier.” Wilson, though, found scientific support for his ideas in esoteric readings of research: if the earth can bend electron and ion beams, then he is on sure-footing postulating pretzel-shaped teleport beams; if rotation and magnetism in correlated in planets and stars, then it could be due to the teleport beams.

Some time toward the mid-1950s, Wilson seems to have relocated to Los Angeles. Or perhaps he had lived their before and continued to shuttle back and forth between Ohio and California: there is some evidence of his moving back and forth. His letters to Russell, written in 1950 and 1951—at least those preserved with the rest of Russell’s papers, give his address as in Cleveland; this is also the time he knew Ellison. (And Thayer, in correspondence with Russell, called the Fortean “Wilson of Cleveland.”) A 1951 letter to John W. Campbell’s “Astounding” is also one more bit of evidence that Wilson was stationed in Ohio.

In 1955, though, his letter to Astounding came from 333 Clay Street, in Los Angeles. His letter to Miller—dated 1 June 1957—had a return address of 1737 East 61st Street, also in Los Angeles. I am not sure what Wilson was doing here. I find no reference to him in reports by or about the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society, though he seems likely to have hooked up with them. In Ellison’s account, Wilson was still going to conventions s late as 1953. (“I saw a man walking toward me. As we neared each other, I recognized him as Al Wilson. I stopped. He came straight up to me, as though he’d known I would be there and had hurried to meet me. There was no preamble, no greetings between two people who who hadn’t seen each other in years. He merely came in close, looked straight at me with those faintly protuberant eyes, and said in an undertone, ‘When you see Stan Skirvin, tell him to examine pages 476 to 495 in T.E. Lawrence’s THE SEVEN PILLARS OF WISDOM.” Then he walked past me and was gone.”) I also do not know what work he was doing. Adding a bit more confusion, there is an Alan F. Wilson listed in the 1956 city directory for Lorain, Ohio. The name, of course, is a common one, so perhaps not too much weight should be placed on it. Still, Lorain is near Cleveland.

Not that the moving changed his interests in reading and theorizing. His 1955 letter to Astounding runs several pages of abstruse reasoning about space travel. The take-home message is that humans should establish refueling stations at specific points to make travel deeper into the solar system possible. His letter to Miller is on completely different topics: anthropology and science fiction. He doubts Margaret Mead’s recent urging to extrapolate current conditions and apply logic to imagine the future—and in support of his opinion offers a quote from Mead’s teacher, Ruth Benedict. The up-shot is that he thinks human future will increasingly be dictated by the free-exercise of will, with only limited constraints implied by nature. Wilson then pivots to bemoan editions of A. E Van Vogt’s books that gut the philosophy from the stories.

After the mid-1950s, evidence of Wilson’s activities are purely speculative, based on shreds of evidence. Between 1958 and 1960, and Alan F. Wilson got married in Cuyahoga county. (Cleveland is the county’s seat.) In 1969, an Alan F. Wilson got divorced in Cleveland. This seems to be the same Alan F. Wilson—though whether it is the same Alan F. Wilson who was a science fiction fan and Fortean is not evident. This Alan F. Wilson had been married for 11 years, which dates the marriage to 1958 or so, coincident with the indexed marriage. His wife’s name was Justine Wilson. She had sued for divorce and grounds of “gross neglect of duty.” In between, the name Alan F. Wilson appeared in Ohio for another reason. Cleveland suffered a 129-day newspaper strike starting 29 November 1962; attempting to fill the gap was “Southwest Press,” which was published by Elmer H. Zelinski starting in March 1963. The editor was Alan F. Wilson. I have not seen copies of this newspaper to confirm any connection, beyond the name, which carries little weight, and Wilson’s amateur interest in publishing, though the Library of Congress does have some, and these may prove or disprove the connection.

Other than that, I have no information on Wilson, either verified or speculative. He was a meteor shooting though the Fortean firmament, its origin and termination a mystery.

**********************

Unlike many Fortean noted in the pages of Doubt, Alan Wilson’s introduction to Fort is documented (though it remains unclear how he came to the Society in the first place), as is his take on Forteanism. His connection to the Fortean Society, though, was brief, lasting only some two or three years: apparently long enough for him to absorb Fortean phenomena into his theories. Wilson had engineering interests—Lavender said he invented some metallurgical techniques, but I have found no evidence of that—and as with other engineering Forteans he took a universal approach to this heterodox ideas, attempting to explain all of existence according to a few principles—those teleporting beams. But unlike the other engineering Forteans, he had a flexibility of thought, too, a willingness to concede that he might never get at the ultimate truth.

Wilson’s first known connection to the Fortean Society came in Doubt 28 (April 1950). Apparently he had corresponded with Thayer, suggesting a method for spreading good ideas: an early form of viral marketing. After writing about the Valun Institute and E.C. Reigel’s, which attacked the government’s monopoly on minting money, Thayer remarked:

“In almost the same mail, MFS Alan Wilson suggests a mean of spreading any good word that comes your way, and if the Valun proposals seem good to you, try out the system with Riegel’s book, or with this issue of DOUBT.

“Wilson’s scheme is an adaptation of the old chain-letter game, which sold a raft of silk stockings in the previous generation, set the country on its ear in the year 6 FS, and more recently started the craze for ‘Pyramid Clubs’. As everybody probably realizes now, the system does not pay off very long when money is involved, but as a means of spreading ideas, without charge, the practice can be very successful. It was employed by the colonists to crystallize opinion and help start the American Revolution.

“It is simply this:

“Whenever a new idea that you think is good swims into your ken, WRITE it to three other people, and ask each of them to WRITE it to three more, if they agree that it is good. It beats writing to your Congressman all hollow. If the idea you wish to propagate is in DOUBT, we will mark the issue and mail it, with an explanatory slip—to names and addresses furnished by you, at the rate of FOUR for a dollar. We’ll pay the postage.”

The idea, as Thayer noted, was not novel: early Forteans, before they *were* Forteans, had engaged in such marketing. (Think of Kenneth MacNichol.) Modernism and its off-shoots—including the Fortean Society—were deeply indebted to business practices and the U.S. mail. But Wilson’s contribution does make clear that he was already a member of the Society, no later than April of 1950, and probably some months before that. (Likely he found his way to the Society through an advertisement or mention in some science fiction magazine, another instance of the importance of magazines in spreading the idea.) Thus, while his time with the Society was short, he was not numbered among those who joined just after World War II and stopped with the turn of the decade; rather, he came in around that turn, and lasted a few years into the 1950s.

It is also clear that this was not Wilson’s only correspondence with Thayer, or Eric Frank Russell. The evidence suggests he was an inveterate letter-writer, though one who occasionally tried to cut back, and it seems by the spring of 1950 he had made an impression on Thayer and Russell. And not a particularly good one. Thayer responded to something seemingly disparaging Russell had said about Wilson in a letter from early May, noting: “What you-all don’t know is how many Alan F Wilsons this land of the free and home of the brave can produce in a bumper season. You get only a random few. Me? Wowee!--to put it mildly. Wilson is probably cracked, but he has flashes of lucidity. He is also a radio ham.” Thayer opened his Society to all manner of cranks, but even as he gave space to their ideas, he didn’t necessarily support them, or think them worthwhile. (His hatred of flying saucers was one of the instances when he let his personal ideas become public.) Judging by the subsequent correspondence, Russell had responded to one of Wilson’s letters, incorporating a cryptic mark about being from “farther away.” It was a reference to Fort—I’m not sure how—but Wilson didn’t understand and “ridiculed” the suggestion.

The irritation continued the next month. Thayer had long had a fraught relationship with postal authorities: he needed them to spread his Society, but ran afoul of their regulations. Early issues of Doubt—before it was *called* Doubt—had prompted some to accuse him of sedition. The FBI periodically looked into the publication and at least once came sniffing around his office. For a time, he was so paranoid he only used his work letterhead and warned Don Bloch not to use the Society’s address. Art Castillo’s dust-up with the draft board caused further headaches. So it was with real emotion that Thayer gave Russell a heads-up on another potential problem with postal authorities. Early in June, he wrote, “Beware of Alan F Wilson, Cleveland. He has outraged the Post Office and we may feel repercussion.” Unfortunately, I do not know what Wilson did to cause problem with the post office; fortunately, nothing seems to have come of the issue.

An example of why Wilson would frustrate Thayer and Russell—though not the postal service-comes from a portion of a letter from him to the both of them preserved with Russell’s papers at the University of Liverpool. It is poorly typed, single spaced and long—two full pages are preserved. There is a logic at work here, and an intelligence, but the foundational principles are so ridiculous that all the ratiocination is not only convoluted but to no particular end, except, perhaps, as the background to a science fiction story. Indeed, that seems to be Wilson’s chief problem, the inability to distinguish between fiction and fact. So he takes not only L. Ron Hubbard’s Diabetics as a statement of genuine science—a poorly considered choice, but one shared by many people—but also Russell’s science fiction novels Dreadful Sanctuary and Sinister Barrier. These last two were never meant to be anything but entertaining yarns. To accept them as statements about reality—disguised or not—shows an incredible naiveté, one that would fully explain Thayer and Russell laughing.

The letter starts with a couple of quotations from Diabetics that seem contradictory. In one, Hubbard suggests that engrams encoded in cells is the very structure of the body; in another, that insanity is somehow an exception to this rule. Wilson points out the contradiction, and tries to save it—insanity must not be a cellular function—but has bigger things on his mind: “Far more importantly, however, I at least am driven to the conclusion that THEY are using Hubbard to draw a ‘red herring’ across the discoveries of Russell revealed in his DREADFUL SANCTUARY . . . . THEY are the US. And they _want_ to communicate with US.

From this preamble, Wilson spins out an incredible scenario. Cells invented human beings, and everything else. Cells are the creatures in Russell’s novel that live on human emotions. But they are not from outside us, they are inside us. We think them moronic—Hubbard’s Reactive Mind—but that is because the communication system between them and us is wobbly. (Subject in its way to the same censors that plagued Thayer and Wilson.) In order for humans to survive, cells had to bequeath to them rationality, a freedom of will, and this—what Hubbard calls our Analytic Mind—makes it hard for humans and cells to communicate. But the cells are trying, sending messages through Hubbard to get the word out. Spaceships are not from space (or as the Theosophically inclined might have it, the ether): they are inside of us.

But cells, for all that they do, are not the ultimate drivers of the universe. No. Cells, themselves, are partially uncontrolled creations of any smaller objects people of the electron. There is, of course, a science fictional equivalent here, too: in the 20s, Ray Cummings wrote a series of stories about sub-atomic people. Maybe Wilson would even admit the connection—seeing Cummings not as a storyteller but, like Russell, a discoverer of scientific truths. We cannot know, though, because here the letter trails off. Still, it is not hard from this excerpt to understand why Thayer and Russell would take to making fun of Wilson and thinking his ideas so outrageous as to be hardly worth considering. Indeed, Thayer would use Wilson as a barometer of unsound thought comparing at least one other Fortean (of whom he did not approve) to the thinker from Cleveland.

Wilson sent a clipping to Russell in July; in August, Thayer told Russell to “continue to ignore Wilson of Cleveland.” Wilson, though, was not discouraged by the lack of response, at least not at first. He received four credits in Doubt 30 (October 1950) and two more in Doubt 31 (January 1951). These ran the gamut of Fortean topics: something about flying saucers (the exact clipping cannot be traced); the appearance of meteors over Cleveland; reports of whales beaching themselves, and public wondering among the press and experts about the reasons for it; and a large meteorite crater announced—the largest in the world, in fact—though scientists would not get around to investigating for another year. (So how’d they know it was so big, was the unexpressed question.) This last clipping, about the perfidity of scientists, pointed toward a political cynicism that Wilson shared with Thayer and Russell.

This dyspeptic view was expressed in his other clippings. One referred to Australian troops shooting at American soldiers in Korea. Another was about a fog that blanketed Cleveland. Wilson knew a pilot who flew up into it and saw there were two layers; no one could smell smoke. And yet officials insisted that the smog was actually smoke from Canadian fires—and when one fire went out, they simply said it was from a different fire. In the course of his report on this unusual fog, Wilson noticed that war time reports had the smell of fire smoke traveling hundreds of miles, which is neither here nor there. The important part was that he called World War II “World Farce II.” Like Thayer, he thought the whole global conflagration was a put-on, something done at the behest of bankers and big business.

It was around this time that Wilson met Ellison. If we can trust Ellison’s memories—two decades old when he originally wrote his piece—then Wilson was a quick study, who had become deeply involved with Forteanism and its cultural cognates. “He was into the Fortean Society and all its unexplained phenomena, Korzybskian General Semantics, heavyweight physical sciences, occultism, and he filed his socks under ‘S’ in the filing cabinet . . . He had a Multilith machine right in the middle of the floor, a Varityper for typing up issues of the club newsletter, and stacks of erudite and obscure books, like Tiffany Thayer’s novels, Fort’s studies of ‘excluded facts,’ what they called ‘a procession of the damned,’ James Branch Cabell, Lord Dunsany, Lovecraft, Lincoln Barnett . . . that whole crowd. There was a cot in the middle of the ‘apartment.’ No sheets. Al slept whenever he felt like it, ate whenever he felt like it, operated off no known clock.” And, indeed, the evidence does seem to bear out some of this recollection. Alan F. Wilson, of Cleveland, was numbered among the members of Institute of General Semantics beginning in 1950 according to the Korzybsian publication “Etc.” (Remember, Thayer thought General Semantics the rich man’s Fort, covering the same ground but with a whole lot of sesquipedalian jargon.)

We get a sense of exactly how Wilson understood Fort and Forteanism from a long letter he wrote to Russell in February 1951 and a letter he wrote to a reverend friend, a version of which he also sent to Russell. Apparently, this was prompted by a letter from Russell—the second one he sent, it would seem. (“You’re a chump to waste time on Wilson. He taut he taw a puddy tat,” Thayer mocked.) By this time, Wilson had deciphered Russell’s earlier cryptic comment, but was still having trouble understanding everything he was saying: “Doubtless you have 1/4 century of Fortean research behind you, while I . . . . . . two years of reading DOUBT and I’m just on WILD TALENTS now. So maybe I don’t catch.” Trying and failing to not send out letters this month, he went on, in a long post script, to connect his theory of a universe composed of teleportation beams to Fortean phenomena—where the cells are in this story, I don’t know:

“From the historic paucity of Canons Diablo or bigger, I figure that there is a natural size limit and natural flow limit to teleport beams, or that big ones are sought out and destroyed by galactic engineers of the planetary phylogenies. Size limit maybe [sic] the size of an elephant or a freight car. Usual beams capable of transport of nothing much bigger than the phylogenetic standard amphibian: Frog. Rana. The only big beams left are very careful engineered for life-transport. Rains of rana. No disasters. Or damned few. Considering the polymorphism of worlds.

“Or the beams caught in a roaring body are broken from stellar contact thereby, and that we only pick up the local life load in the broken portion of the beam. When the pipe runs dry, we still have the beam, but its energy peters out, or it shrinks to the core of the earth and builds up potential along with other beams. Some day and outshooting blaze of beams [sic]. Big Big beams. That the galactic will pounce on and snuff out quicklike. Or engineer for life transport again. In general the big beams will come in at the poles of the ecliptic if contact is intentional and intended to be quasi-permanent. Auroras. In general all big beams have been and are being seized by galactic and engineered to contact any planetary system from its ecliptic poles, for minimum beam-distortion.”

In his letter to the reverend, dated the same day, Wilson notes that he had recently obtained all but three back issues of Doubt, “and although I have not had time to read them completely, I find them more than just entertaining.” Here was the pay-off of his political views on Forteanism as well as his scientific ones. He differed with the reverend’s conclusion that Doubt was part-line communist. (Thayer would have laughed.) As an opening salvo, he noted that Thayer, the Fortean Society, and George Seldes (who published In Fact) all recommended reading “The Christian Science Monitor”—hardly, then, the mark of a party-line communist publication. He came back to the point again at the end of the letter.

He was concerned with what he called the propaganda of the KVN Axis, which referred to the interrelated efforts of the Kremlin, Vatican, and something abbreviated NAM, and probably referred to the National Association of Manufacturers. That is to say, Wilson was not only worried about communism; not only worried about religion; he was also worried about big business. The triumvirate controlled America. He went on to point out that there was a great deal of propaganda surrounding the Korean war, and it was not clear if China was involved at all or the number of troops on the communist side. The point was not to excuse communism but to suggest—in a manner that would have won Thayer’s approval—that the entire war was being used to control the people. Everyday citizens were being manipulated for the nefarious ends of the powers-that-be.

After his remarks absolving the Fortean Society of hiding water for the communists, Wilson pivoted away from Forteanism to Fort himself, and his relations to Wilson’s metaphysics:

“I know what you mean by being ‘letdown’ upon reading Fort. I’ve just waded my way through the first 95% of THE BOOKS in the last couple of weeks. There have been times when I’ve been so enraged by his concentration upon explicable trivia that I wanted to throw my 4 dollar investment into my 5 dollar waste basket. However, I confess to lifelong inconsistency and to harboring irreconcilables within ‘me’.

“But from general semantics, into which I had gone by myself long before I ever heard of Kouzybski, or of Charles Fort who preceded him on almost every major axiom of g.s., I bear in mind that ‘the map is not the territory’ or that the ‘explicable’ has no necessary or/and sufficient relation to ‘the truth,’ the latter being unknowable, except insofar as ‘knowing’ is recognized as an approximate function or ‘quasi’-function of quasi-existent similar but not identical machines called brains. [sic]

“This sounds like the creation of a new obscurantism does it not? It is not my desire to aid the creation of any such thing.

“When I was a child and before I had filled myself full of high-order-probability systems, such as euclidean mathematics and the chemistry and physics of alleged ‘atoms’ and so-called ‘compounds’, I had a couple or 3 times the terrifying thought, usually in the middle of a bright sunshiny afternoon in the country, Suppose Our House isn’t there when I get home——-just a grassy meadow? if I turn around once, will those two trees I am looking at still be there when I look again?

“And this: why SHOULD they be there?

“This leads (a) to the anatomy of ‘should’ and/or ‘ought’, and (b) to a view of the universe as being a tightly-bound one-ness, or to the Newton-Einstein formalism which Fort calls ‘universality’ and which modern science calls ‘modern science’.

“Since (b) is a single answer to a question which obviously has more than one answer, I choose to consider (a) also.

“Ought a chair to remain still on the floor of one’s room? Ought the dishes on the dinner table remain on the dinner table, barring the facetious? Ought earth-quakes to be due solely to contraction and tidal forces and internal fissions, fusions and radioactivities? Ought dust clouds always follow volcanic eruptions and seldom procede [sic] them? Ought life to be confined o planetary surficial loci [sic] and to planetary surficial forms? Ought earth to be free from contact now and forever with any alleged life having a stellar or a deep-space evolution?

“The absolute answer to every one of these questions is a resounding YES.

“And you know that you are no more of an Absolutist than Fort is or was. In the Newton-Einstein formalism, you and Fort are parts of the same space-time plenum. There. . . . . the 2 of you already have 2 major points in common.

“In the Fort or universe-is-an-egg formalism, you and Fort are possibly parts of an indefinable quasi-something.

“To me there is no conflict between these formalisms. How could there be? They both exist inside my skull and I dislike headaches, and they are BOTH THERE, so, irreconcilable or not, they are both TRUE. My brains is as slippery as any Fort ever cursed——-but the slipperiness is on the INSIDE in my case, so that the data or alleged data ARE allowed to enter, and then they can bounce around in a finite but unbounded trajectory of reflections from the polished interior walls of my braincase. The transit time from reflection to reflection allows memories to ENDURE and give existence to MIND.

“Similarly the interstellar transit time of tablets of gold massproduced [sic] near Canopus and flushed out on teleport beams helter-skelter on finite and unbounded but sometimes planetary-interrupted trajectories allows cosmic memories to ENDURE and gives existence to (one-of-several_ cosmic MINDS. And if bits of Spirellum Rubrum cling to said tablets of gold, or if amphibian beings such as frogs are flushed out on separate missions by the millions or millions of millions, they too give endurance to memory and existence to mind.

“And some wheres micro beings like us may have mastered the teleports. And some galaxy else wheres (like here) the teleports may have unconsciously (like the carbon-atom -chains in pre-archaezoic Earth oceans) combined with each other and/or with and blazing suns and/or with many (or one) planetary fleck of nuclear ash to form a primitive organism. The telescopes of this Earth known to humans have not yet revealed any data to indicate that if one such organism exists, very large numbers of them should not exist. That teleport beams exist, that they do not exist, that they form organisms, that they do not form organisms——none of these views is in the slightest conflict with Newton, Einstein or Fort. ‘Belief’ in any of these views, i am sure, meet with as hearty disapproval from Einstein or a reincarnated Newton as it would from a revivified-corpse-of-Charles-Fort. This is also my attitude, and I am quite sure it is yours.”

That ended the section on Wilson’s scientific thought—his ontology—and its connection with Fort. I do not want to pretend I understand his ideas very intensively—I do not—but it seems to me that what he is suggesting is the existence of a living, monistic universe that has intelligence operating on many levels, from the sub-atomic through the cellular, from animals and humans to a cosmic mind, each level incorporating those below it, but not perfectly: as in quantum dynamics, each level also follows its own rules. This arrangement, he suggests, gives rise to certain Fortean phenomena—poltergeists, rains of frogs—while other bits of Forteana he considers ridiculous, and already explained—presumably here he is referring to Fort’s highly heterodox astrological suppositions.

This letter seems to have the zenith of Wilson’s Fortean career. It is tempting to speculate—though impossible to prove—that having gotten what he needed from reading all of Fort and most of the Fortean Society magazine, he had little reason to keep connected. He had absorbed those parts of Fort and Forteanism of which he approved into his own system of thought, jettisoned the rest, and moved on—to what, we do not know. The letters to Russell and the reverend were written in February 1951. His last appearance in Doubt came in October 1952, but many of these cannot be dated, and so it is possible he stopped sending in material even earlier.

He appeared twice in March 1951 (Doubt 32) with material that was sent in before his letters to Russell. One clipping dealt with mystery explosions; another with the disappearance of the stone of scone and similar statuary mysteries. Seven months later, in Doubt 33, he was acknowledged for sending in material which was not used in the issue. He received a similarly generic credit in the following issue. Two issues on, in April 1952, he was mentioned regarding a clipping from the Cleveland Plain Dealer about the collapse of a water tank, which killed four. Before the accident, a fireball was seen plunging toward the tank—Thayer implied it was a meteor. The final appearance of his name in the pages of Doubt, issue 38, October 1952, two-and-a-half years after his first, was another generic credit in a long list of them.

Thus ended his Fortean career. As far as I know.

Wilson was an intelligent man, according to Ellison, and based on his writings, but a confused one, as well. Rooted in science fiction, he seems to have blurred the boundaries between fact and literature to such an extent that he could not tell the difference. Pulp stories became discoveries about the structure of the universe. The fact son journalism were being used to write a story in which everyday people were pawns for the powerful. He came to the Fortean Society not through Fort, but through Forteanism found his way to reading Fort—and, in all likelihood, his path to Forteanism was also through science fiction. He stayed, it seems, because he found Thayer’s politics salutary. And he stayed because there was something he wanted to extract from Fort and Forteanism. He was writing the universe’s story, a tale that involved subatomic intelligences, cosmic minds, and, connecting everything, teleportation beams. Fort and the Fortean Society provided data for his story and—for a short time—a place to send his ideas. They didn’t spread, though: mostly, they died. Did that mean they weren’t good ideas? Or just not acceptable ones? Either way, for someone looking to geometrically increase the spread of his ideas, this situation was less than ideal. It is not hard to see why Wilson became a Fortean—nor is it hard to understand why, shortly after he did, he quit.

His ideas about the universe were deeply rooted in science fictional concepts. In early 1951, he wrote to Russell:

“I see the universe tentatively as network [sic] of teleport beams, some natural, some manufactured or engineered, some organic. The natural ones are geodesic or straight when unperturbed by ‘bodies’. Gravitic fields of passing star and/or planets catch the beams, pull them in, maintain a temporary contact, then snap away again. The beams often pass right into the core of the earth, and give rise to simultaneous seismic, atmospheric and polt[ergeist] phenomena at epochs of ‘contact’ and ‘break’. The rotating earth will seize a beam and twist it or ‘wind’ it about the earth until the tensions become so great that rupture must occur. At the points of entry and exit, the beam will be normal or nearly so to the earth’s surface, so that teleports will seem to be up-and-down and the appearing and disappearing points will seem to be stationary with respect to the earth’s surface for a time.

[new paragraph:] “Engineered teleport beams will be special engineered for minimum damage to planets and their life. Hence some of the gentle effects. Natural beams will boil up whole rows of volcanoes on occasion. The organic beams may partake of paternalistic vampirism, but you indicate that we are principally ignored. So long as we stay small and obscure. But it is death for nuclear powered trout. The sun grabs most of the teleport beams, but Earth picks up a few every day I think, and drops a similar number. All those that are momently [sic] grabbed by Luna are also grabbed by Earth, and all those that are grabbed by Earth are also grabbed by Helios. Canon Diablo.”

There are obvious connections between this conception of the universe and Shaverism, which Wilson does not deny. Later in the same letter, he called Shaver’s ideas “The tracing of ancient cosmic contacts.” There are also echoes of Russell’s writings, what with the psychic vampirism recalling his “Sinister Barrier.” Wilson, though, found scientific support for his ideas in esoteric readings of research: if the earth can bend electron and ion beams, then he is on sure-footing postulating pretzel-shaped teleport beams; if rotation and magnetism in correlated in planets and stars, then it could be due to the teleport beams.

Some time toward the mid-1950s, Wilson seems to have relocated to Los Angeles. Or perhaps he had lived their before and continued to shuttle back and forth between Ohio and California: there is some evidence of his moving back and forth. His letters to Russell, written in 1950 and 1951—at least those preserved with the rest of Russell’s papers, give his address as in Cleveland; this is also the time he knew Ellison. (And Thayer, in correspondence with Russell, called the Fortean “Wilson of Cleveland.”) A 1951 letter to John W. Campbell’s “Astounding” is also one more bit of evidence that Wilson was stationed in Ohio.

In 1955, though, his letter to Astounding came from 333 Clay Street, in Los Angeles. His letter to Miller—dated 1 June 1957—had a return address of 1737 East 61st Street, also in Los Angeles. I am not sure what Wilson was doing here. I find no reference to him in reports by or about the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society, though he seems likely to have hooked up with them. In Ellison’s account, Wilson was still going to conventions s late as 1953. (“I saw a man walking toward me. As we neared each other, I recognized him as Al Wilson. I stopped. He came straight up to me, as though he’d known I would be there and had hurried to meet me. There was no preamble, no greetings between two people who who hadn’t seen each other in years. He merely came in close, looked straight at me with those faintly protuberant eyes, and said in an undertone, ‘When you see Stan Skirvin, tell him to examine pages 476 to 495 in T.E. Lawrence’s THE SEVEN PILLARS OF WISDOM.” Then he walked past me and was gone.”) I also do not know what work he was doing. Adding a bit more confusion, there is an Alan F. Wilson listed in the 1956 city directory for Lorain, Ohio. The name, of course, is a common one, so perhaps not too much weight should be placed on it. Still, Lorain is near Cleveland.

Not that the moving changed his interests in reading and theorizing. His 1955 letter to Astounding runs several pages of abstruse reasoning about space travel. The take-home message is that humans should establish refueling stations at specific points to make travel deeper into the solar system possible. His letter to Miller is on completely different topics: anthropology and science fiction. He doubts Margaret Mead’s recent urging to extrapolate current conditions and apply logic to imagine the future—and in support of his opinion offers a quote from Mead’s teacher, Ruth Benedict. The up-shot is that he thinks human future will increasingly be dictated by the free-exercise of will, with only limited constraints implied by nature. Wilson then pivots to bemoan editions of A. E Van Vogt’s books that gut the philosophy from the stories.

After the mid-1950s, evidence of Wilson’s activities are purely speculative, based on shreds of evidence. Between 1958 and 1960, and Alan F. Wilson got married in Cuyahoga county. (Cleveland is the county’s seat.) In 1969, an Alan F. Wilson got divorced in Cleveland. This seems to be the same Alan F. Wilson—though whether it is the same Alan F. Wilson who was a science fiction fan and Fortean is not evident. This Alan F. Wilson had been married for 11 years, which dates the marriage to 1958 or so, coincident with the indexed marriage. His wife’s name was Justine Wilson. She had sued for divorce and grounds of “gross neglect of duty.” In between, the name Alan F. Wilson appeared in Ohio for another reason. Cleveland suffered a 129-day newspaper strike starting 29 November 1962; attempting to fill the gap was “Southwest Press,” which was published by Elmer H. Zelinski starting in March 1963. The editor was Alan F. Wilson. I have not seen copies of this newspaper to confirm any connection, beyond the name, which carries little weight, and Wilson’s amateur interest in publishing, though the Library of Congress does have some, and these may prove or disprove the connection.

Other than that, I have no information on Wilson, either verified or speculative. He was a meteor shooting though the Fortean firmament, its origin and termination a mystery.

**********************

Unlike many Fortean noted in the pages of Doubt, Alan Wilson’s introduction to Fort is documented (though it remains unclear how he came to the Society in the first place), as is his take on Forteanism. His connection to the Fortean Society, though, was brief, lasting only some two or three years: apparently long enough for him to absorb Fortean phenomena into his theories. Wilson had engineering interests—Lavender said he invented some metallurgical techniques, but I have found no evidence of that—and as with other engineering Forteans he took a universal approach to this heterodox ideas, attempting to explain all of existence according to a few principles—those teleporting beams. But unlike the other engineering Forteans, he had a flexibility of thought, too, a willingness to concede that he might never get at the ultimate truth.

Wilson’s first known connection to the Fortean Society came in Doubt 28 (April 1950). Apparently he had corresponded with Thayer, suggesting a method for spreading good ideas: an early form of viral marketing. After writing about the Valun Institute and E.C. Reigel’s, which attacked the government’s monopoly on minting money, Thayer remarked:

“In almost the same mail, MFS Alan Wilson suggests a mean of spreading any good word that comes your way, and if the Valun proposals seem good to you, try out the system with Riegel’s book, or with this issue of DOUBT.

“Wilson’s scheme is an adaptation of the old chain-letter game, which sold a raft of silk stockings in the previous generation, set the country on its ear in the year 6 FS, and more recently started the craze for ‘Pyramid Clubs’. As everybody probably realizes now, the system does not pay off very long when money is involved, but as a means of spreading ideas, without charge, the practice can be very successful. It was employed by the colonists to crystallize opinion and help start the American Revolution.

“It is simply this:

“Whenever a new idea that you think is good swims into your ken, WRITE it to three other people, and ask each of them to WRITE it to three more, if they agree that it is good. It beats writing to your Congressman all hollow. If the idea you wish to propagate is in DOUBT, we will mark the issue and mail it, with an explanatory slip—to names and addresses furnished by you, at the rate of FOUR for a dollar. We’ll pay the postage.”

The idea, as Thayer noted, was not novel: early Forteans, before they *were* Forteans, had engaged in such marketing. (Think of Kenneth MacNichol.) Modernism and its off-shoots—including the Fortean Society—were deeply indebted to business practices and the U.S. mail. But Wilson’s contribution does make clear that he was already a member of the Society, no later than April of 1950, and probably some months before that. (Likely he found his way to the Society through an advertisement or mention in some science fiction magazine, another instance of the importance of magazines in spreading the idea.) Thus, while his time with the Society was short, he was not numbered among those who joined just after World War II and stopped with the turn of the decade; rather, he came in around that turn, and lasted a few years into the 1950s.

It is also clear that this was not Wilson’s only correspondence with Thayer, or Eric Frank Russell. The evidence suggests he was an inveterate letter-writer, though one who occasionally tried to cut back, and it seems by the spring of 1950 he had made an impression on Thayer and Russell. And not a particularly good one. Thayer responded to something seemingly disparaging Russell had said about Wilson in a letter from early May, noting: “What you-all don’t know is how many Alan F Wilsons this land of the free and home of the brave can produce in a bumper season. You get only a random few. Me? Wowee!--to put it mildly. Wilson is probably cracked, but he has flashes of lucidity. He is also a radio ham.” Thayer opened his Society to all manner of cranks, but even as he gave space to their ideas, he didn’t necessarily support them, or think them worthwhile. (His hatred of flying saucers was one of the instances when he let his personal ideas become public.) Judging by the subsequent correspondence, Russell had responded to one of Wilson’s letters, incorporating a cryptic mark about being from “farther away.” It was a reference to Fort—I’m not sure how—but Wilson didn’t understand and “ridiculed” the suggestion.

The irritation continued the next month. Thayer had long had a fraught relationship with postal authorities: he needed them to spread his Society, but ran afoul of their regulations. Early issues of Doubt—before it was *called* Doubt—had prompted some to accuse him of sedition. The FBI periodically looked into the publication and at least once came sniffing around his office. For a time, he was so paranoid he only used his work letterhead and warned Don Bloch not to use the Society’s address. Art Castillo’s dust-up with the draft board caused further headaches. So it was with real emotion that Thayer gave Russell a heads-up on another potential problem with postal authorities. Early in June, he wrote, “Beware of Alan F Wilson, Cleveland. He has outraged the Post Office and we may feel repercussion.” Unfortunately, I do not know what Wilson did to cause problem with the post office; fortunately, nothing seems to have come of the issue.

An example of why Wilson would frustrate Thayer and Russell—though not the postal service-comes from a portion of a letter from him to the both of them preserved with Russell’s papers at the University of Liverpool. It is poorly typed, single spaced and long—two full pages are preserved. There is a logic at work here, and an intelligence, but the foundational principles are so ridiculous that all the ratiocination is not only convoluted but to no particular end, except, perhaps, as the background to a science fiction story. Indeed, that seems to be Wilson’s chief problem, the inability to distinguish between fiction and fact. So he takes not only L. Ron Hubbard’s Diabetics as a statement of genuine science—a poorly considered choice, but one shared by many people—but also Russell’s science fiction novels Dreadful Sanctuary and Sinister Barrier. These last two were never meant to be anything but entertaining yarns. To accept them as statements about reality—disguised or not—shows an incredible naiveté, one that would fully explain Thayer and Russell laughing.

The letter starts with a couple of quotations from Diabetics that seem contradictory. In one, Hubbard suggests that engrams encoded in cells is the very structure of the body; in another, that insanity is somehow an exception to this rule. Wilson points out the contradiction, and tries to save it—insanity must not be a cellular function—but has bigger things on his mind: “Far more importantly, however, I at least am driven to the conclusion that THEY are using Hubbard to draw a ‘red herring’ across the discoveries of Russell revealed in his DREADFUL SANCTUARY . . . . THEY are the US. And they _want_ to communicate with US.

From this preamble, Wilson spins out an incredible scenario. Cells invented human beings, and everything else. Cells are the creatures in Russell’s novel that live on human emotions. But they are not from outside us, they are inside us. We think them moronic—Hubbard’s Reactive Mind—but that is because the communication system between them and us is wobbly. (Subject in its way to the same censors that plagued Thayer and Wilson.) In order for humans to survive, cells had to bequeath to them rationality, a freedom of will, and this—what Hubbard calls our Analytic Mind—makes it hard for humans and cells to communicate. But the cells are trying, sending messages through Hubbard to get the word out. Spaceships are not from space (or as the Theosophically inclined might have it, the ether): they are inside of us.

But cells, for all that they do, are not the ultimate drivers of the universe. No. Cells, themselves, are partially uncontrolled creations of any smaller objects people of the electron. There is, of course, a science fictional equivalent here, too: in the 20s, Ray Cummings wrote a series of stories about sub-atomic people. Maybe Wilson would even admit the connection—seeing Cummings not as a storyteller but, like Russell, a discoverer of scientific truths. We cannot know, though, because here the letter trails off. Still, it is not hard from this excerpt to understand why Thayer and Russell would take to making fun of Wilson and thinking his ideas so outrageous as to be hardly worth considering. Indeed, Thayer would use Wilson as a barometer of unsound thought comparing at least one other Fortean (of whom he did not approve) to the thinker from Cleveland.

Wilson sent a clipping to Russell in July; in August, Thayer told Russell to “continue to ignore Wilson of Cleveland.” Wilson, though, was not discouraged by the lack of response, at least not at first. He received four credits in Doubt 30 (October 1950) and two more in Doubt 31 (January 1951). These ran the gamut of Fortean topics: something about flying saucers (the exact clipping cannot be traced); the appearance of meteors over Cleveland; reports of whales beaching themselves, and public wondering among the press and experts about the reasons for it; and a large meteorite crater announced—the largest in the world, in fact—though scientists would not get around to investigating for another year. (So how’d they know it was so big, was the unexpressed question.) This last clipping, about the perfidity of scientists, pointed toward a political cynicism that Wilson shared with Thayer and Russell.

This dyspeptic view was expressed in his other clippings. One referred to Australian troops shooting at American soldiers in Korea. Another was about a fog that blanketed Cleveland. Wilson knew a pilot who flew up into it and saw there were two layers; no one could smell smoke. And yet officials insisted that the smog was actually smoke from Canadian fires—and when one fire went out, they simply said it was from a different fire. In the course of his report on this unusual fog, Wilson noticed that war time reports had the smell of fire smoke traveling hundreds of miles, which is neither here nor there. The important part was that he called World War II “World Farce II.” Like Thayer, he thought the whole global conflagration was a put-on, something done at the behest of bankers and big business.

It was around this time that Wilson met Ellison. If we can trust Ellison’s memories—two decades old when he originally wrote his piece—then Wilson was a quick study, who had become deeply involved with Forteanism and its cultural cognates. “He was into the Fortean Society and all its unexplained phenomena, Korzybskian General Semantics, heavyweight physical sciences, occultism, and he filed his socks under ‘S’ in the filing cabinet . . . He had a Multilith machine right in the middle of the floor, a Varityper for typing up issues of the club newsletter, and stacks of erudite and obscure books, like Tiffany Thayer’s novels, Fort’s studies of ‘excluded facts,’ what they called ‘a procession of the damned,’ James Branch Cabell, Lord Dunsany, Lovecraft, Lincoln Barnett . . . that whole crowd. There was a cot in the middle of the ‘apartment.’ No sheets. Al slept whenever he felt like it, ate whenever he felt like it, operated off no known clock.” And, indeed, the evidence does seem to bear out some of this recollection. Alan F. Wilson, of Cleveland, was numbered among the members of Institute of General Semantics beginning in 1950 according to the Korzybsian publication “Etc.” (Remember, Thayer thought General Semantics the rich man’s Fort, covering the same ground but with a whole lot of sesquipedalian jargon.)

We get a sense of exactly how Wilson understood Fort and Forteanism from a long letter he wrote to Russell in February 1951 and a letter he wrote to a reverend friend, a version of which he also sent to Russell. Apparently, this was prompted by a letter from Russell—the second one he sent, it would seem. (“You’re a chump to waste time on Wilson. He taut he taw a puddy tat,” Thayer mocked.) By this time, Wilson had deciphered Russell’s earlier cryptic comment, but was still having trouble understanding everything he was saying: “Doubtless you have 1/4 century of Fortean research behind you, while I . . . . . . two years of reading DOUBT and I’m just on WILD TALENTS now. So maybe I don’t catch.” Trying and failing to not send out letters this month, he went on, in a long post script, to connect his theory of a universe composed of teleportation beams to Fortean phenomena—where the cells are in this story, I don’t know:

“From the historic paucity of Canons Diablo or bigger, I figure that there is a natural size limit and natural flow limit to teleport beams, or that big ones are sought out and destroyed by galactic engineers of the planetary phylogenies. Size limit maybe [sic] the size of an elephant or a freight car. Usual beams capable of transport of nothing much bigger than the phylogenetic standard amphibian: Frog. Rana. The only big beams left are very careful engineered for life-transport. Rains of rana. No disasters. Or damned few. Considering the polymorphism of worlds.

“Or the beams caught in a roaring body are broken from stellar contact thereby, and that we only pick up the local life load in the broken portion of the beam. When the pipe runs dry, we still have the beam, but its energy peters out, or it shrinks to the core of the earth and builds up potential along with other beams. Some day and outshooting blaze of beams [sic]. Big Big beams. That the galactic will pounce on and snuff out quicklike. Or engineer for life transport again. In general the big beams will come in at the poles of the ecliptic if contact is intentional and intended to be quasi-permanent. Auroras. In general all big beams have been and are being seized by galactic and engineered to contact any planetary system from its ecliptic poles, for minimum beam-distortion.”

In his letter to the reverend, dated the same day, Wilson notes that he had recently obtained all but three back issues of Doubt, “and although I have not had time to read them completely, I find them more than just entertaining.” Here was the pay-off of his political views on Forteanism as well as his scientific ones. He differed with the reverend’s conclusion that Doubt was part-line communist. (Thayer would have laughed.) As an opening salvo, he noted that Thayer, the Fortean Society, and George Seldes (who published In Fact) all recommended reading “The Christian Science Monitor”—hardly, then, the mark of a party-line communist publication. He came back to the point again at the end of the letter.

He was concerned with what he called the propaganda of the KVN Axis, which referred to the interrelated efforts of the Kremlin, Vatican, and something abbreviated NAM, and probably referred to the National Association of Manufacturers. That is to say, Wilson was not only worried about communism; not only worried about religion; he was also worried about big business. The triumvirate controlled America. He went on to point out that there was a great deal of propaganda surrounding the Korean war, and it was not clear if China was involved at all or the number of troops on the communist side. The point was not to excuse communism but to suggest—in a manner that would have won Thayer’s approval—that the entire war was being used to control the people. Everyday citizens were being manipulated for the nefarious ends of the powers-that-be.

After his remarks absolving the Fortean Society of hiding water for the communists, Wilson pivoted away from Forteanism to Fort himself, and his relations to Wilson’s metaphysics:

“I know what you mean by being ‘letdown’ upon reading Fort. I’ve just waded my way through the first 95% of THE BOOKS in the last couple of weeks. There have been times when I’ve been so enraged by his concentration upon explicable trivia that I wanted to throw my 4 dollar investment into my 5 dollar waste basket. However, I confess to lifelong inconsistency and to harboring irreconcilables within ‘me’.

“But from general semantics, into which I had gone by myself long before I ever heard of Kouzybski, or of Charles Fort who preceded him on almost every major axiom of g.s., I bear in mind that ‘the map is not the territory’ or that the ‘explicable’ has no necessary or/and sufficient relation to ‘the truth,’ the latter being unknowable, except insofar as ‘knowing’ is recognized as an approximate function or ‘quasi’-function of quasi-existent similar but not identical machines called brains. [sic]

“This sounds like the creation of a new obscurantism does it not? It is not my desire to aid the creation of any such thing.

“When I was a child and before I had filled myself full of high-order-probability systems, such as euclidean mathematics and the chemistry and physics of alleged ‘atoms’ and so-called ‘compounds’, I had a couple or 3 times the terrifying thought, usually in the middle of a bright sunshiny afternoon in the country, Suppose Our House isn’t there when I get home——-just a grassy meadow? if I turn around once, will those two trees I am looking at still be there when I look again?

“And this: why SHOULD they be there?

“This leads (a) to the anatomy of ‘should’ and/or ‘ought’, and (b) to a view of the universe as being a tightly-bound one-ness, or to the Newton-Einstein formalism which Fort calls ‘universality’ and which modern science calls ‘modern science’.

“Since (b) is a single answer to a question which obviously has more than one answer, I choose to consider (a) also.

“Ought a chair to remain still on the floor of one’s room? Ought the dishes on the dinner table remain on the dinner table, barring the facetious? Ought earth-quakes to be due solely to contraction and tidal forces and internal fissions, fusions and radioactivities? Ought dust clouds always follow volcanic eruptions and seldom procede [sic] them? Ought life to be confined o planetary surficial loci [sic] and to planetary surficial forms? Ought earth to be free from contact now and forever with any alleged life having a stellar or a deep-space evolution?

“The absolute answer to every one of these questions is a resounding YES.

“And you know that you are no more of an Absolutist than Fort is or was. In the Newton-Einstein formalism, you and Fort are parts of the same space-time plenum. There. . . . . the 2 of you already have 2 major points in common.

“In the Fort or universe-is-an-egg formalism, you and Fort are possibly parts of an indefinable quasi-something.

“To me there is no conflict between these formalisms. How could there be? They both exist inside my skull and I dislike headaches, and they are BOTH THERE, so, irreconcilable or not, they are both TRUE. My brains is as slippery as any Fort ever cursed——-but the slipperiness is on the INSIDE in my case, so that the data or alleged data ARE allowed to enter, and then they can bounce around in a finite but unbounded trajectory of reflections from the polished interior walls of my braincase. The transit time from reflection to reflection allows memories to ENDURE and give existence to MIND.

“Similarly the interstellar transit time of tablets of gold massproduced [sic] near Canopus and flushed out on teleport beams helter-skelter on finite and unbounded but sometimes planetary-interrupted trajectories allows cosmic memories to ENDURE and gives existence to (one-of-several_ cosmic MINDS. And if bits of Spirellum Rubrum cling to said tablets of gold, or if amphibian beings such as frogs are flushed out on separate missions by the millions or millions of millions, they too give endurance to memory and existence to mind.

“And some wheres micro beings like us may have mastered the teleports. And some galaxy else wheres (like here) the teleports may have unconsciously (like the carbon-atom -chains in pre-archaezoic Earth oceans) combined with each other and/or with and blazing suns and/or with many (or one) planetary fleck of nuclear ash to form a primitive organism. The telescopes of this Earth known to humans have not yet revealed any data to indicate that if one such organism exists, very large numbers of them should not exist. That teleport beams exist, that they do not exist, that they form organisms, that they do not form organisms——none of these views is in the slightest conflict with Newton, Einstein or Fort. ‘Belief’ in any of these views, i am sure, meet with as hearty disapproval from Einstein or a reincarnated Newton as it would from a revivified-corpse-of-Charles-Fort. This is also my attitude, and I am quite sure it is yours.”

That ended the section on Wilson’s scientific thought—his ontology—and its connection with Fort. I do not want to pretend I understand his ideas very intensively—I do not—but it seems to me that what he is suggesting is the existence of a living, monistic universe that has intelligence operating on many levels, from the sub-atomic through the cellular, from animals and humans to a cosmic mind, each level incorporating those below it, but not perfectly: as in quantum dynamics, each level also follows its own rules. This arrangement, he suggests, gives rise to certain Fortean phenomena—poltergeists, rains of frogs—while other bits of Forteana he considers ridiculous, and already explained—presumably here he is referring to Fort’s highly heterodox astrological suppositions.

This letter seems to have the zenith of Wilson’s Fortean career. It is tempting to speculate—though impossible to prove—that having gotten what he needed from reading all of Fort and most of the Fortean Society magazine, he had little reason to keep connected. He had absorbed those parts of Fort and Forteanism of which he approved into his own system of thought, jettisoned the rest, and moved on—to what, we do not know. The letters to Russell and the reverend were written in February 1951. His last appearance in Doubt came in October 1952, but many of these cannot be dated, and so it is possible he stopped sending in material even earlier.

He appeared twice in March 1951 (Doubt 32) with material that was sent in before his letters to Russell. One clipping dealt with mystery explosions; another with the disappearance of the stone of scone and similar statuary mysteries. Seven months later, in Doubt 33, he was acknowledged for sending in material which was not used in the issue. He received a similarly generic credit in the following issue. Two issues on, in April 1952, he was mentioned regarding a clipping from the Cleveland Plain Dealer about the collapse of a water tank, which killed four. Before the accident, a fireball was seen plunging toward the tank—Thayer implied it was a meteor. The final appearance of his name in the pages of Doubt, issue 38, October 1952, two-and-a-half years after his first, was another generic credit in a long list of them.

Thus ended his Fortean career. As far as I know.

Wilson was an intelligent man, according to Ellison, and based on his writings, but a confused one, as well. Rooted in science fiction, he seems to have blurred the boundaries between fact and literature to such an extent that he could not tell the difference. Pulp stories became discoveries about the structure of the universe. The fact son journalism were being used to write a story in which everyday people were pawns for the powerful. He came to the Fortean Society not through Fort, but through Forteanism found his way to reading Fort—and, in all likelihood, his path to Forteanism was also through science fiction. He stayed, it seems, because he found Thayer’s politics salutary. And he stayed because there was something he wanted to extract from Fort and Forteanism. He was writing the universe’s story, a tale that involved subatomic intelligences, cosmic minds, and, connecting everything, teleportation beams. Fort and the Fortean Society provided data for his story and—for a short time—a place to send his ideas. They didn’t spread, though: mostly, they died. Did that mean they weren’t good ideas? Or just not acceptable ones? Either way, for someone looking to geometrically increase the spread of his ideas, this situation was less than ideal. It is not hard to see why Wilson became a Fortean—nor is it hard to understand why, shortly after he did, he quit.