Saturday Evening Post, 30 April 1949.

Saturday Evening Post, 30 April 1949. Tracking down an unserious—and uncertain—Fortean. And his stalwart Fortean brother.

Six times between 1947 and 1952 the name MFS Hall appeared in Doubt. Here, then, was another Fortean attracted to the cause in the second half of the 1940s, but whose interest did not last much into the following decade. There’s definitely a pattern. But what to make of the name? Hall is an incredibly common surname. By all rights, he should have ended up in the long list of Fortean members I did not have enough information about to track down; just another name that I tagged “red” for unknown. Except, there were clues . . .

The most important of these came in a letter he wrote to Thayer that ran in Doubt 28, April 1950. In the course of it, he noted he had a brother named Charles Landes, and another with a doctorate in metallurgy. Their father was a civil engineer. They had lived in Nebraska and Portland, but at least some of the family was now moving about California. This was enough to identify the family.

Six times between 1947 and 1952 the name MFS Hall appeared in Doubt. Here, then, was another Fortean attracted to the cause in the second half of the 1940s, but whose interest did not last much into the following decade. There’s definitely a pattern. But what to make of the name? Hall is an incredibly common surname. By all rights, he should have ended up in the long list of Fortean members I did not have enough information about to track down; just another name that I tagged “red” for unknown. Except, there were clues . . .

The most important of these came in a letter he wrote to Thayer that ran in Doubt 28, April 1950. In the course of it, he noted he had a brother named Charles Landes, and another with a doctorate in metallurgy. Their father was a civil engineer. They had lived in Nebraska and Portland, but at least some of the family was now moving about California. This was enough to identify the family.

Alan Edward Hall—MFS Hall—was born 1 April 1923—no wonder, then, he tended toward the jocular in in his Fortean dealings—to Edward Hall and Helen (Bennett) Hall in Portland, Oregon. Edward was a civil engineer from Nebraska. Helen was also from Nebraska; trained as a concert pianist, she played for Omaha’s First Unitarian Church—making the family inheritors of America’s transcendentalist tradition. (Edward’s middle name suggested the same: The M stood for Manlove.) Edward was born 10 June 1888, Helen November 1893, and they were married around 1918, likely in Salinas, Kansas, where Edward was working for a railroad. That was where they were in 1920, as well, childless still.

Sometime thereafter, they moved to Portland, where there three sons were born, Lewis D 24 November 1920; Alan E 1 April 1923; and Charles Landes, 4 September 1925. The quick succession of boys, after several years of childlessness, suggests that the Halls were not unfamiliar with birth control. By 1930, the family had returned to Nebraska, where they lived with the two mother-in-laws, Althea Bennett and Flora Hall—no doubt helpful with three boys all under ten. No later than 1935, they moved from a house on Chicago Street to one on Cass Street; right around the time that the last of their children—a girl, at last!—was born: Suzanne Hall, on 23 January 1935. By 1940, all the children were still in the house, but the two grandmothers had passed on, leaving Helen with her hands full.

Lewis D. Hall did take a degree and became a professor of metallurgy. It seems he may have been an instructor at the University of Chicago briefly—1947 to 1949—before heading West. He did some summer instruction at the University of California and then became attached to Stanford University no later than 1950. Lewis married and had two children, both boys, Stephen and Christopher. At some point much later, he was connected to the University of Arizona, but that may have been temporary. He died in Palo Alto June, 1985, just shy of his 65th birthday. Lewis’s migration may have set the pattern for the family—or merely continued it; in 1951, Edward and Helen also moved to California, likely bringing with them Charles and Suzanne. Alan was already on the Left Coast, which may have been additional impetus for the other Halls to leave Nebraska.

It is harder to trace what happened with the rest of the family. I cannot find any record related to Charles and the second World War. (He might have been just a little too young.) He did marry and, like Lewis, had two children—both girls!—Cathi and Coral. He seemed to move about the state a bit, at times near Palo Alto, other times in Southern California. (He would also live in San Diego and Everett, Washington.) He had inherited some of the family’s fixation on manipulating materials—its engineering tradition—and took out a patent on a vacuum joint in 1965, when he was in Palo Alto. The patent, though, was registered in Great Britain, and not by the United States. Suzanne may have attended the University of California—it’s hard to be sure, given how common the name was—but doesn’t seem to have married. She was living near her parents in 1967, when her mother passed, she in Corte Madera, them in Marin. She died 30 May 1986, having just turned fifty one. Edward Manlike Hall, the paterfamilias, died 5 February 1981, a few months short of his 93rd birthday.

Alan was in Los Angeles no later than September 25 September 1945, aged 22. He seems to have done some college, but not finished it—the 1940 census credited him with one year, but his enlistment papers state he only had four years of high school. He was classified as belonging among “skilled painters, construction and maintenance” when he joined the war effort that September at Fort Macarthur in San Pedro. He seems to have stayed in San Pedro after returning to civilian life, where he worked as a sign painter. In the later 1960s he moved to long beach, then ended up in Corte Madera in the eighties. That was a bade decade for the Hall family. Edward, Lewis, and Suzanne all died then. So did Alan.

Alan E. Hall died in July 1987, aged 64. Charles was the last of his nuclear family. He died 17 August 2000, aged 74. He had returned to Omaha, and that was where he passed away.

***************************

The name Hall first appears in Doubt 19 (October 1947), the issue devoted to flying saucers. There it is on page 290, in a paragraph on members who contributed to the issue. There’s no way to connect the name to any particular clipping, nor even anyway to know whether the contributor was Alan or Charles Fort. Indeed, it is not clear how either came to Forteanism or Fort, though it seems likely that Alan was the contributor to the Fortean Society, and a member, while Charles was an enthusiastic fan, maybe never belonging to the Society at all. Two pages later, the name Hall appeared again, inside another paragraph of contributors, this time listing those who sent in material on something other than saucers. (Thayer titled the column “At the Same Time.”) Once more, it is impossible to tie the name to any particular material. Worth noting, though, is the fact that, by his own admission, Alan Hall was considering dropping his membership in the middle of 1948, which does suggest that he was a member before that, and so may have been the contributor.

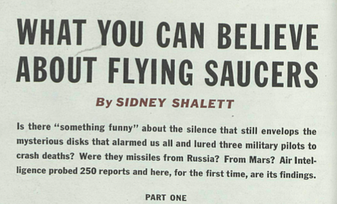

It was flying saucers that made the two Landes’ apparent. In the April 30 and May 7, 1949, issues of the Saturday Evening Post ran a story by Sid Shalett called “What You Can Believe About Flying Saucers.” This was a few years after both Robert Heinlein and Robert Spencer had broken into the magazine with science fiction stories. Shalett had, according to himself, been intrigued by the mystery of flying saucers, but after investigating—and having his material vetted, if not approved, by the Air Force—he became a firm skeptic. The Air Force had found no evidence to support the contention that the flying disks were from other countries on earth, or other planets, he said, and in the second part tried to explain away the phenomena as the result of optical illusions. Shalett also drew Fort into the discussion—as had other journalists such as the Fortean Marcia Winn—simultaneously using his work to discredit recent report and dismissing him as belonging to some species of crank:

“One of the tentative decisions made by [The U.S. Air Force’s] Project Saucer early in the game is that there’s nothing new in any of this. Strong suggestions of it appear in the published works of the late Charles Fort, a writer from the Bronx, who spent a lifetime collecting obscure references to the unexplained phenomena of the ages. One of Fort’s theses was that Science was a fraud. Nobody was ever quite sure whether Fort was serious or had his tongue in his cheek, but the intelligence officers waded through four of his books. Fort, they learned, had reports of elephant-sized hailstones, orange-flavored and horned hailstones, flying disks, snowflakes the size of plates, and strange airborne visitations of beef, blood, butter, coal, salt, black powder, axes, clinkers, bricks, fireballs, human bodies, fish, frogs, toads, serpents, ants, worms and even a haycock.Most of the phenomena were slimly documented, many being based solely on newspaper-filler items telling about purported freaks of nature.

“When I went to Wright Field armed only with reports of what witnesses said they had seen, the Great Flying Saucer Scare seemed reasonably mysterious to me. When I had finished my investigation in Dayton, Washington and elsewhere, the thing seemed less mysterious than odd. There are any number of logical and perfectly normal solutions by which most of the saucer sightings can be explained.”

The story sparked some responses from readers, and four letters appeared in the 4 June issue. Josef Israels, II, from New York, noted that he had reported on an aerial phenomena in Egypt back in 1935 that ran on the front page of the New York Times, and he thought that explaining the sight as a planet—probably Venus—made much sense; he praised Shalett’s investigation. Alfred E. Suckow, from Havre, Montana, said he, too, had seen saucers in August 1948, lined up in groups of one, two, or four; though they didn’t move, they are a “wonderful sight.” But he was willing to believe the explanation offered by someone in his group that they were reflections of sunlight off copper wires of a newly built power lines. Grant M. McLaughlin, from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, made a joke of the subject: “You owe it to your reading public to inform them that the Flying Saucers are either reflections of or segments of our U.S. Public Debt.”

That the Saturday Evening Post editors thought flying saucers were a joke—misidentifications at best, hoaxes at worst—is clear, and not only from McLaughlin’s letter. In the middle of the later form the Montana man they inserted a comic strip of a disheveled cowboy, crawling through the desert—there’s the obligatory cow skull in the corner—imagining flying saucers above him—flying saucers of ice cream and great big mugs of milkshakes. They were a mirage. The point was hammered home in their response to the other letter, this the only one taking exception with Shalett’s conclusions. It was authored by Charles L. Hall of San Pedro, California, and heavily edited. (All the ellipses are in the printed version of the magazine, as is the editorial insertion.)

“Am up in arms over a paragraph . . . which . . . blithely refers to Charles Fort, without a doubt one of the truly great and open-minded thinkers this country as ever produced, as though he were a demented charlatan . . .

“[Mr. Shalett actually described Fort as ‘a writer from the Bronx who spent a lifetime collecting obscure references to the unexplained phenomena of the ages. One of Fort’s theses was that science was a fraud. Nobody was ever quite sure whether Fort was serious or had his tongue in his cheek. . . .’]

Instead of most of Fort’s phenomena being ‘slimly documented’ . . . they were mainly taken from reports in ‘scientific’ journals, meteorological periodicals, etc. . . . To anyone but a closed-minded scientist, ‘Intelligence Officer,’ or smug reporter, it is obvious that there have been and still are innumerable things which have come to this earth from regions outside it . . .”

The letter, like the original article, attracted some notice. The editors could not resist commenting beyond their insertion: “We’ll string along with the closed-minded scientists, intelligence officers and smug reporters,” they quipped. Thayer noted the letter in Doubt 27 (September 1949), as well as the original piece, noting the correspondence of the publication with a whole series of fireballs and discs across the country:

“These reports coincided with the release of the Saturday Evening Post dated April 30, and with a more or less subtle red-herring press hand-out from the AP wire under a Washington date-line, April 27,

“The San Francisco Chronicle, of all papers [Thayer thought the Chronicle especially simple-minded], actually printed this parenthesis in the middle of the story:

“‘(Release of the Air Force statement coincided with he appearance on the newsstands of the Saturday Eveing Post for April 30, containing an article baed on some of the same information.)’

“The article was a two-parter written to order for the armed forces by Sidney Shallot, who corresponded with YS through the preparation of his piece of propaganda.”

Thayer then went on to document more saucer reports—though he hated the entire topic—before coming, in chronological order, to Hall’s letter:

“The Satevepost of June 4 printed one pro-Fortean protest, so you may be assured that the ED received hundreds. If he had only a few they would have been ignored entirely.”

The letter must have also gotten Thayer thinking—it was from a man surnamed Hall from San Pedro, California, and, apparently he also had a member, surnamed Hall, from the same city. So he wrote to the Hall, Alan, asking if there was any connection, and reprinted Alan’s response in Doubt 28, April 1950 (ellipses in original):

“In regards to your epistle of 12/29/19 FS, in which you and somebody else (just who, it is not made clear) were observing the June 4 (old style) SATURDAY EVENING POST (God save the Queen), I must answer in the affirmative.

“This Chas. L. (Landes) Hall is a distant brother of mine, on my great grandmother’s side, by way of Omaha, Nebr., and Portland, Ore. Is this perfectly clear? Then please explain it to me, because I’m all confused.

When C. L. sent his indignant letter into the SEP (GstQ), he did not expect the editors of that staid, conservative pulp to print it.

“After seeing what they printed, he wished they hadn’t.

“Which all counts up to the PROVABLE FACT that the said editors cut out practically 100% of the real meaning of the letter, and about 90% of the contents. (This last statement is open to controversy.)

“I myself did not see the epistle in complete form, as it was written while C.L. was up in Los Angeles or Hollywood, or some such other dismal outpost of society, and did not make a carbon copy. The letter, I am much afraid, was scathing indeed to the orthodox editors of the Post. Anyway they sure mangled it.

“Charley is a bit rabid on the subject of Forteans. I myself prefer the middle road, enjoying the mad scramble and doubting considerably, but with no foaming at the mouth.

“We two are a bit outcast in the family, as the pater is a civil engineer of long standing, and the oldest brother is a PH.D. in Metallurgy (Caps are his) now breaking iron wires at several hundred degrees below zero Farengrade or Centerheit or something, just for the merry hell of it, as far as yours truly can observe. They both seem to take any aspersions on Newton’s Laws (Caps Newton’s) as personal affronts on themselves, although lately the Pater has become interested in maybe having a look into the Books, so perhaps another convert in the future. Who knows?

“About a year and a half ago I was ready to cut myself off from the society, as I thought there were too many fanatics connected with it. It seems to me that an acute swing away from orthodoxy, to the point where all orthodoxy is impartially sneered at, is just as bad as being an orthodoxy worshipper.

“Did not Fort himself laugh at life?????

“And another thing . . . the fanatics seem to regard Fort as a God, in a sense . . . which is liable, in time, to drag the society down to the level of an organized religion . . . too many converts take it too seriously. Not that I don’t think it’s great and all that, but I don’t think anybody is going to save humanity with it . . . just building up another set of symbols or idols or something to what effect? The original aim should be fulfilled . . . Doubt everything, possibly, give a new set of working hypotheses for awhile. But the human mind will inevitably bog down, and you will never have a large percentage of the population WANTING to THINK, so let’s just get the convivial minds. The right people are in the wrong places and all that.

“However, I’ll keep paying my dues and sending in available data, when available, or when I get around to reading the D.A. yellow dog sheets, as the mag Doubt is still the best reading of anything I see, from a purely disinterested standpoint.

“We are having the usual unusual weather out here. It’s raining, but not frogs or fishes, damn it.”

That Thayer titled the jokey letter “MFS HALL WRITES” suggests that Alan was the only Hall to formally belong to the Society. Likely, then, it was the same Alan Hall who contributed the last three bits to Doubt, and not Charles. These were all small pieces, all in 1952. In April, two years after his letter appeared (Doubt 36), Hall’s name once again appeared in a long paragraph of credits—so his contribution cannot be identified. But he had a parenthetical aside, too, which explains this absence from the pages of Doubt: “(I ain’t been sending any data because I can’t stand to read newspapers.)” A few months later (June, Doubt 37), there was a squib attributed to his name. This one came under the title “Hi-Spots in the Mail,” which suggests that there may have been continuing correspondence between Thayer and Hall. It was a completely tongue-in-cheek suggestion for a new map—although it is unknown what suggested it, beyond Hall’s basic biographical history:

“A GREAT NEW PROJECTION HAS BEEN LOST TO POSTERITY! Only trouble with the Mercator Projection is that it emphasises [sic] the wrong things. Now my proposed projection, on the Mercator principle, would have an East Pole and a West Pole. The West Pole would center in Omaha, Neb. (I was raised there) and would be represented on the map as a line across the top. This would spread the great U.S. and A all over the top of the map, where it belongs, and would make it bigger than Asia or Africa, reducing Roosia to insignificant size.”

Hall’s final contribution came in the next issue, Doubt 38, from October 1952. Under title “Very Quakey”—which comprised stories of earthquakes Thayer had received—Hall was noted as writing from San Pedro that he saw “several nice intense flashes of who knows what” (light, not sound, is indicated) during the big roll in California at 5 AM July 21.

All of which isn’t a lot to go on. Obviously, Charles Hall was a big fan of Fort, at least for a time in the late 1940s—big enough fan to write into the Saturday Evening Post and have his brother saying he foamed at the mouth. It’s impossible to overlook, given Alan’s letter, the likely psychosocial dimension to Charles’ enthusiasm, a kind of rebellion against his father and older brother. That same dynamic may have been at work with Alan, too, although to a lesser extent, as what he seemed to find in the Fortean Society (and Fort) was humor; new ways to look at the world; and chances to prick holes in pompous gasbags. Neither his commitment to the Society nor to the kind of corroding skepticism that Thayer practiced. (Fort’s skepticism was much more lightly held, it seems to me.) There seems to have been something in the second half of the 1940s that made Fort and the Society devoted to him especially attractive that did not translate as well to the 1950s. What is was—if it even existed—is worth considering.

Sometime thereafter, they moved to Portland, where there three sons were born, Lewis D 24 November 1920; Alan E 1 April 1923; and Charles Landes, 4 September 1925. The quick succession of boys, after several years of childlessness, suggests that the Halls were not unfamiliar with birth control. By 1930, the family had returned to Nebraska, where they lived with the two mother-in-laws, Althea Bennett and Flora Hall—no doubt helpful with three boys all under ten. No later than 1935, they moved from a house on Chicago Street to one on Cass Street; right around the time that the last of their children—a girl, at last!—was born: Suzanne Hall, on 23 January 1935. By 1940, all the children were still in the house, but the two grandmothers had passed on, leaving Helen with her hands full.

Lewis D. Hall did take a degree and became a professor of metallurgy. It seems he may have been an instructor at the University of Chicago briefly—1947 to 1949—before heading West. He did some summer instruction at the University of California and then became attached to Stanford University no later than 1950. Lewis married and had two children, both boys, Stephen and Christopher. At some point much later, he was connected to the University of Arizona, but that may have been temporary. He died in Palo Alto June, 1985, just shy of his 65th birthday. Lewis’s migration may have set the pattern for the family—or merely continued it; in 1951, Edward and Helen also moved to California, likely bringing with them Charles and Suzanne. Alan was already on the Left Coast, which may have been additional impetus for the other Halls to leave Nebraska.

It is harder to trace what happened with the rest of the family. I cannot find any record related to Charles and the second World War. (He might have been just a little too young.) He did marry and, like Lewis, had two children—both girls!—Cathi and Coral. He seemed to move about the state a bit, at times near Palo Alto, other times in Southern California. (He would also live in San Diego and Everett, Washington.) He had inherited some of the family’s fixation on manipulating materials—its engineering tradition—and took out a patent on a vacuum joint in 1965, when he was in Palo Alto. The patent, though, was registered in Great Britain, and not by the United States. Suzanne may have attended the University of California—it’s hard to be sure, given how common the name was—but doesn’t seem to have married. She was living near her parents in 1967, when her mother passed, she in Corte Madera, them in Marin. She died 30 May 1986, having just turned fifty one. Edward Manlike Hall, the paterfamilias, died 5 February 1981, a few months short of his 93rd birthday.

Alan was in Los Angeles no later than September 25 September 1945, aged 22. He seems to have done some college, but not finished it—the 1940 census credited him with one year, but his enlistment papers state he only had four years of high school. He was classified as belonging among “skilled painters, construction and maintenance” when he joined the war effort that September at Fort Macarthur in San Pedro. He seems to have stayed in San Pedro after returning to civilian life, where he worked as a sign painter. In the later 1960s he moved to long beach, then ended up in Corte Madera in the eighties. That was a bade decade for the Hall family. Edward, Lewis, and Suzanne all died then. So did Alan.

Alan E. Hall died in July 1987, aged 64. Charles was the last of his nuclear family. He died 17 August 2000, aged 74. He had returned to Omaha, and that was where he passed away.

***************************

The name Hall first appears in Doubt 19 (October 1947), the issue devoted to flying saucers. There it is on page 290, in a paragraph on members who contributed to the issue. There’s no way to connect the name to any particular clipping, nor even anyway to know whether the contributor was Alan or Charles Fort. Indeed, it is not clear how either came to Forteanism or Fort, though it seems likely that Alan was the contributor to the Fortean Society, and a member, while Charles was an enthusiastic fan, maybe never belonging to the Society at all. Two pages later, the name Hall appeared again, inside another paragraph of contributors, this time listing those who sent in material on something other than saucers. (Thayer titled the column “At the Same Time.”) Once more, it is impossible to tie the name to any particular material. Worth noting, though, is the fact that, by his own admission, Alan Hall was considering dropping his membership in the middle of 1948, which does suggest that he was a member before that, and so may have been the contributor.

It was flying saucers that made the two Landes’ apparent. In the April 30 and May 7, 1949, issues of the Saturday Evening Post ran a story by Sid Shalett called “What You Can Believe About Flying Saucers.” This was a few years after both Robert Heinlein and Robert Spencer had broken into the magazine with science fiction stories. Shalett had, according to himself, been intrigued by the mystery of flying saucers, but after investigating—and having his material vetted, if not approved, by the Air Force—he became a firm skeptic. The Air Force had found no evidence to support the contention that the flying disks were from other countries on earth, or other planets, he said, and in the second part tried to explain away the phenomena as the result of optical illusions. Shalett also drew Fort into the discussion—as had other journalists such as the Fortean Marcia Winn—simultaneously using his work to discredit recent report and dismissing him as belonging to some species of crank:

“One of the tentative decisions made by [The U.S. Air Force’s] Project Saucer early in the game is that there’s nothing new in any of this. Strong suggestions of it appear in the published works of the late Charles Fort, a writer from the Bronx, who spent a lifetime collecting obscure references to the unexplained phenomena of the ages. One of Fort’s theses was that Science was a fraud. Nobody was ever quite sure whether Fort was serious or had his tongue in his cheek, but the intelligence officers waded through four of his books. Fort, they learned, had reports of elephant-sized hailstones, orange-flavored and horned hailstones, flying disks, snowflakes the size of plates, and strange airborne visitations of beef, blood, butter, coal, salt, black powder, axes, clinkers, bricks, fireballs, human bodies, fish, frogs, toads, serpents, ants, worms and even a haycock.Most of the phenomena were slimly documented, many being based solely on newspaper-filler items telling about purported freaks of nature.

“When I went to Wright Field armed only with reports of what witnesses said they had seen, the Great Flying Saucer Scare seemed reasonably mysterious to me. When I had finished my investigation in Dayton, Washington and elsewhere, the thing seemed less mysterious than odd. There are any number of logical and perfectly normal solutions by which most of the saucer sightings can be explained.”

The story sparked some responses from readers, and four letters appeared in the 4 June issue. Josef Israels, II, from New York, noted that he had reported on an aerial phenomena in Egypt back in 1935 that ran on the front page of the New York Times, and he thought that explaining the sight as a planet—probably Venus—made much sense; he praised Shalett’s investigation. Alfred E. Suckow, from Havre, Montana, said he, too, had seen saucers in August 1948, lined up in groups of one, two, or four; though they didn’t move, they are a “wonderful sight.” But he was willing to believe the explanation offered by someone in his group that they were reflections of sunlight off copper wires of a newly built power lines. Grant M. McLaughlin, from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, made a joke of the subject: “You owe it to your reading public to inform them that the Flying Saucers are either reflections of or segments of our U.S. Public Debt.”

That the Saturday Evening Post editors thought flying saucers were a joke—misidentifications at best, hoaxes at worst—is clear, and not only from McLaughlin’s letter. In the middle of the later form the Montana man they inserted a comic strip of a disheveled cowboy, crawling through the desert—there’s the obligatory cow skull in the corner—imagining flying saucers above him—flying saucers of ice cream and great big mugs of milkshakes. They were a mirage. The point was hammered home in their response to the other letter, this the only one taking exception with Shalett’s conclusions. It was authored by Charles L. Hall of San Pedro, California, and heavily edited. (All the ellipses are in the printed version of the magazine, as is the editorial insertion.)

“Am up in arms over a paragraph . . . which . . . blithely refers to Charles Fort, without a doubt one of the truly great and open-minded thinkers this country as ever produced, as though he were a demented charlatan . . .

“[Mr. Shalett actually described Fort as ‘a writer from the Bronx who spent a lifetime collecting obscure references to the unexplained phenomena of the ages. One of Fort’s theses was that science was a fraud. Nobody was ever quite sure whether Fort was serious or had his tongue in his cheek. . . .’]

Instead of most of Fort’s phenomena being ‘slimly documented’ . . . they were mainly taken from reports in ‘scientific’ journals, meteorological periodicals, etc. . . . To anyone but a closed-minded scientist, ‘Intelligence Officer,’ or smug reporter, it is obvious that there have been and still are innumerable things which have come to this earth from regions outside it . . .”

The letter, like the original article, attracted some notice. The editors could not resist commenting beyond their insertion: “We’ll string along with the closed-minded scientists, intelligence officers and smug reporters,” they quipped. Thayer noted the letter in Doubt 27 (September 1949), as well as the original piece, noting the correspondence of the publication with a whole series of fireballs and discs across the country:

“These reports coincided with the release of the Saturday Evening Post dated April 30, and with a more or less subtle red-herring press hand-out from the AP wire under a Washington date-line, April 27,

“The San Francisco Chronicle, of all papers [Thayer thought the Chronicle especially simple-minded], actually printed this parenthesis in the middle of the story:

“‘(Release of the Air Force statement coincided with he appearance on the newsstands of the Saturday Eveing Post for April 30, containing an article baed on some of the same information.)’

“The article was a two-parter written to order for the armed forces by Sidney Shallot, who corresponded with YS through the preparation of his piece of propaganda.”

Thayer then went on to document more saucer reports—though he hated the entire topic—before coming, in chronological order, to Hall’s letter:

“The Satevepost of June 4 printed one pro-Fortean protest, so you may be assured that the ED received hundreds. If he had only a few they would have been ignored entirely.”

The letter must have also gotten Thayer thinking—it was from a man surnamed Hall from San Pedro, California, and, apparently he also had a member, surnamed Hall, from the same city. So he wrote to the Hall, Alan, asking if there was any connection, and reprinted Alan’s response in Doubt 28, April 1950 (ellipses in original):

“In regards to your epistle of 12/29/19 FS, in which you and somebody else (just who, it is not made clear) were observing the June 4 (old style) SATURDAY EVENING POST (God save the Queen), I must answer in the affirmative.

“This Chas. L. (Landes) Hall is a distant brother of mine, on my great grandmother’s side, by way of Omaha, Nebr., and Portland, Ore. Is this perfectly clear? Then please explain it to me, because I’m all confused.

When C. L. sent his indignant letter into the SEP (GstQ), he did not expect the editors of that staid, conservative pulp to print it.

“After seeing what they printed, he wished they hadn’t.

“Which all counts up to the PROVABLE FACT that the said editors cut out practically 100% of the real meaning of the letter, and about 90% of the contents. (This last statement is open to controversy.)

“I myself did not see the epistle in complete form, as it was written while C.L. was up in Los Angeles or Hollywood, or some such other dismal outpost of society, and did not make a carbon copy. The letter, I am much afraid, was scathing indeed to the orthodox editors of the Post. Anyway they sure mangled it.

“Charley is a bit rabid on the subject of Forteans. I myself prefer the middle road, enjoying the mad scramble and doubting considerably, but with no foaming at the mouth.

“We two are a bit outcast in the family, as the pater is a civil engineer of long standing, and the oldest brother is a PH.D. in Metallurgy (Caps are his) now breaking iron wires at several hundred degrees below zero Farengrade or Centerheit or something, just for the merry hell of it, as far as yours truly can observe. They both seem to take any aspersions on Newton’s Laws (Caps Newton’s) as personal affronts on themselves, although lately the Pater has become interested in maybe having a look into the Books, so perhaps another convert in the future. Who knows?

“About a year and a half ago I was ready to cut myself off from the society, as I thought there were too many fanatics connected with it. It seems to me that an acute swing away from orthodoxy, to the point where all orthodoxy is impartially sneered at, is just as bad as being an orthodoxy worshipper.

“Did not Fort himself laugh at life?????

“And another thing . . . the fanatics seem to regard Fort as a God, in a sense . . . which is liable, in time, to drag the society down to the level of an organized religion . . . too many converts take it too seriously. Not that I don’t think it’s great and all that, but I don’t think anybody is going to save humanity with it . . . just building up another set of symbols or idols or something to what effect? The original aim should be fulfilled . . . Doubt everything, possibly, give a new set of working hypotheses for awhile. But the human mind will inevitably bog down, and you will never have a large percentage of the population WANTING to THINK, so let’s just get the convivial minds. The right people are in the wrong places and all that.

“However, I’ll keep paying my dues and sending in available data, when available, or when I get around to reading the D.A. yellow dog sheets, as the mag Doubt is still the best reading of anything I see, from a purely disinterested standpoint.

“We are having the usual unusual weather out here. It’s raining, but not frogs or fishes, damn it.”

That Thayer titled the jokey letter “MFS HALL WRITES” suggests that Alan was the only Hall to formally belong to the Society. Likely, then, it was the same Alan Hall who contributed the last three bits to Doubt, and not Charles. These were all small pieces, all in 1952. In April, two years after his letter appeared (Doubt 36), Hall’s name once again appeared in a long paragraph of credits—so his contribution cannot be identified. But he had a parenthetical aside, too, which explains this absence from the pages of Doubt: “(I ain’t been sending any data because I can’t stand to read newspapers.)” A few months later (June, Doubt 37), there was a squib attributed to his name. This one came under the title “Hi-Spots in the Mail,” which suggests that there may have been continuing correspondence between Thayer and Hall. It was a completely tongue-in-cheek suggestion for a new map—although it is unknown what suggested it, beyond Hall’s basic biographical history:

“A GREAT NEW PROJECTION HAS BEEN LOST TO POSTERITY! Only trouble with the Mercator Projection is that it emphasises [sic] the wrong things. Now my proposed projection, on the Mercator principle, would have an East Pole and a West Pole. The West Pole would center in Omaha, Neb. (I was raised there) and would be represented on the map as a line across the top. This would spread the great U.S. and A all over the top of the map, where it belongs, and would make it bigger than Asia or Africa, reducing Roosia to insignificant size.”

Hall’s final contribution came in the next issue, Doubt 38, from October 1952. Under title “Very Quakey”—which comprised stories of earthquakes Thayer had received—Hall was noted as writing from San Pedro that he saw “several nice intense flashes of who knows what” (light, not sound, is indicated) during the big roll in California at 5 AM July 21.

All of which isn’t a lot to go on. Obviously, Charles Hall was a big fan of Fort, at least for a time in the late 1940s—big enough fan to write into the Saturday Evening Post and have his brother saying he foamed at the mouth. It’s impossible to overlook, given Alan’s letter, the likely psychosocial dimension to Charles’ enthusiasm, a kind of rebellion against his father and older brother. That same dynamic may have been at work with Alan, too, although to a lesser extent, as what he seemed to find in the Fortean Society (and Fort) was humor; new ways to look at the world; and chances to prick holes in pompous gasbags. Neither his commitment to the Society nor to the kind of corroding skepticism that Thayer practiced. (Fort’s skepticism was much more lightly held, it seems to me.) There seems to have been something in the second half of the 1940s that made Fort and the Society devoted to him especially attractive that did not translate as well to the 1950s. What is was—if it even existed—is worth considering.