A brief notice about a well-known figure.

According to Tiffany Thayer, Abraham Merritt was a member “almost from its founding.” But he only appeared in its pages rarely.

Professionally, Merritt was a journalist, and a very high paid one, which allowed him to indulge in a number of hobbies, including travel, collecting artifacts, and gardening. He worked for the Sunday newspaper supplement American Weekly, as an assistant from 1912 to 1937 and then as editor from 1937 to 1943. The paper ran vaguely Fortean stories—tales of mystery and speculative history.

Merritt was a writer of weird tales from the late teens through the 1930s, influencing the development of science fiction and fantasy to come (particularly H.P. Lovecraft and Richard Shaver). His tales were in the pulp tradition—with swashbuckling heroes and damsels in distress and the most villainous of villains—but the prose was florid, instead of clipped. Active at the same time as Fort, it is possible there was mutual influence, but it is hard to track.

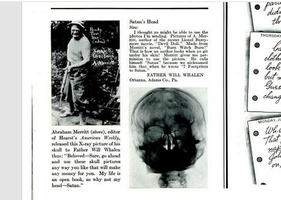

Doubt first mentioned Merritt in December 1943—noting that he had died. He was fifty-nine, struck by a heart attack. Thayer only gave his passing a line. He was mentioned again in Doubt 21 (June 1948), his name listed among those indexed in Everett Bleiler’s The Checklist of Fantastic Fiction. He did a rate a picture, as well as a few words, in Doubt 26 (October 19490, but was only a topic of conversation because his poker buddy Father Will Whalen was found dead in a fire of unknown origin (prompting Thayer to speculate it was spontaneous combustion). Years before, Whalen and Merritt had taken each other’s pictures and Thayer had received copies. The picture of Merritt showed him bare chested and holding a pick. A handwritten caption said, “Ready for the critics. Xmas greetings. A. Merritt.” (The same image was used in Life magazine in 1936.) Thayer’s write up was clearly designed to take up space: the two small pictures and a few lines of text drowned in the white blankness of the page.

It seems a fitting metaphor for the connection between Merritt and Fort: disappointing how little there is.

According to Tiffany Thayer, Abraham Merritt was a member “almost from its founding.” But he only appeared in its pages rarely.

Professionally, Merritt was a journalist, and a very high paid one, which allowed him to indulge in a number of hobbies, including travel, collecting artifacts, and gardening. He worked for the Sunday newspaper supplement American Weekly, as an assistant from 1912 to 1937 and then as editor from 1937 to 1943. The paper ran vaguely Fortean stories—tales of mystery and speculative history.

Merritt was a writer of weird tales from the late teens through the 1930s, influencing the development of science fiction and fantasy to come (particularly H.P. Lovecraft and Richard Shaver). His tales were in the pulp tradition—with swashbuckling heroes and damsels in distress and the most villainous of villains—but the prose was florid, instead of clipped. Active at the same time as Fort, it is possible there was mutual influence, but it is hard to track.

Doubt first mentioned Merritt in December 1943—noting that he had died. He was fifty-nine, struck by a heart attack. Thayer only gave his passing a line. He was mentioned again in Doubt 21 (June 1948), his name listed among those indexed in Everett Bleiler’s The Checklist of Fantastic Fiction. He did a rate a picture, as well as a few words, in Doubt 26 (October 19490, but was only a topic of conversation because his poker buddy Father Will Whalen was found dead in a fire of unknown origin (prompting Thayer to speculate it was spontaneous combustion). Years before, Whalen and Merritt had taken each other’s pictures and Thayer had received copies. The picture of Merritt showed him bare chested and holding a pick. A handwritten caption said, “Ready for the critics. Xmas greetings. A. Merritt.” (The same image was used in Life magazine in 1936.) Thayer’s write up was clearly designed to take up space: the two small pictures and a few lines of text drowned in the white blankness of the page.

It seems a fitting metaphor for the connection between Merritt and Fort: disappointing how little there is.