Almost unknown, he was yet one of the most important of the Fortean Society founders.

Aaron Sussman was born in Russia, 10 December 1903 (or maybe 25 December—the confusion may reflect that Russia was still using the Julian calendar when Aaron was born), making him just a few months younger than Tiffany Thayer, and a full generation behind Charles Fort. His parents were Saul and Adele; they had arrived in New York City on 25 August 1906. Their native language was Yiddish, but by 1920 Saul and Adele could both speak English. The Sussmans had five children; Arron—also styled Aren—was the eldest; three of them had been born in the United States. Saul supported the family as a sign painter. In 1920, the seventeen-year old Aaron was in school, too young to have served in World War I. He attended college at some point in his life, but never finished.

Five years later, before he turned 22, Aaron married the former Carolyn Wallach. It was 14 May 1925. I don’t have reliable information on Carolyn, but it is possible she was a few years younger than Aaron, born sometime between 1904 and 1908, to Austrian immigrants. If that’s correct, Carolyn—or Caroline, or even Corolina—may have left her family early, a lodger according to the 1915 New York census, when she was about ten, and a private nurse working for a family according to the 1920 census, when she was about 16. The 1930 census had the renting a place on 48th Street in Queens. They had a radio, and Aaron was now naturalized. (Saul, his father, had applied for naturalization in 1922, which likely conferred citizenship upon Aaron.) Aaron was working as a publisher for a book concern—and books would be at the center of the rest of his life. In particular, selling books.

Aaron Sussman was born in Russia, 10 December 1903 (or maybe 25 December—the confusion may reflect that Russia was still using the Julian calendar when Aaron was born), making him just a few months younger than Tiffany Thayer, and a full generation behind Charles Fort. His parents were Saul and Adele; they had arrived in New York City on 25 August 1906. Their native language was Yiddish, but by 1920 Saul and Adele could both speak English. The Sussmans had five children; Arron—also styled Aren—was the eldest; three of them had been born in the United States. Saul supported the family as a sign painter. In 1920, the seventeen-year old Aaron was in school, too young to have served in World War I. He attended college at some point in his life, but never finished.

Five years later, before he turned 22, Aaron married the former Carolyn Wallach. It was 14 May 1925. I don’t have reliable information on Carolyn, but it is possible she was a few years younger than Aaron, born sometime between 1904 and 1908, to Austrian immigrants. If that’s correct, Carolyn—or Caroline, or even Corolina—may have left her family early, a lodger according to the 1915 New York census, when she was about ten, and a private nurse working for a family according to the 1920 census, when she was about 16. The 1930 census had the renting a place on 48th Street in Queens. They had a radio, and Aaron was now naturalized. (Saul, his father, had applied for naturalization in 1922, which likely conferred citizenship upon Aaron.) Aaron was working as a publisher for a book concern—and books would be at the center of the rest of his life. In particular, selling books.

According to legend, Sussman got his start with boldness. (Almost as though he is the ur-source for Don Draper, showing up in the office of a hung-over Roger Sterling, inventing a job offer that had been accepted.) As the story goes, was having lunch when he overheard a man at a nearby table bemoaning the death of his wife's prized purebred schnauzer. “I’d pay $300 for another,” he said. Susan offered to sell him one and, after the man accepted, Susan returned to his table, smiling, telling his companions now he just had to find out what a schnauzer was. Another story, this one told by publishing magnate Bennett Cerf, had Susan buying a mouse trap only to find he had no bait. So he cut a picture of cheese from a woman’s magazine, put it on the trap—and caught his mouse. Unbelievable? Sure. The point was, he could sell—he knew the power of advertising, and could wield it to snag even the wiliest.

By his own account, Sussman started in the publishing business first with G. P. Putnam’s Sons, and then with Horace Liveright, Inc.—note that it was Boni & Liveright which published Charles Fort’s first two books—doing editorial and promotional chores. In April 1930, he became a partner in Claude Kendall’s publishing venture (although the name of the firm did not change). Kendall was an interesting character, about whom little has been written. He worked for the United Press in Argentina for a time, before returning to the States and opening his own publishing business. He was a provocateur. His first book was “Uncle Sham," an attack on the United States by Indian writer Kanhayalal Gauba. (There's a Fortean connection here, as for years Thayer’s would run in Doubt excerpts of Gauba’s “The Pathology of Princes” under the title “The Truth about India.”) With Sussman, Kendall published Russian writer Andre Sobol’s collecion “Freak Show,” Octave Mirbeau’s sado-masochistic “Torture Garden” (translated by Alvah Bessie, whom Susan may have known as a younger man), the banned-in-Canada “Twisted Clay,” and Alexandra David-Neel’s esoteric classic—which would become a touch-point in the Shaver mystery of the 1940s—“Magic and Mystery in Tibet.” He tried to obtain the rights to the sure-to-be-censored “Ulysses,” by James Joyce. The second book they put out was Thayer's first novel “Thirteen Men,” and Kendall, at least, would publish three others Thayer novels, “Call Her Savage,” “Thirteen Men,” and “An American Girl.” (Sussman declined Thayer’s “The Illustrious Corpse,” thinking it would sell better as a more cheaply priced book; the subsequent publication of that novel got Thayer in legal trouble, and Sussman was dragged into it.) Of course, Kendall also published Fort’s last two books—Sussman designed both.

Thayer left Kendall in 1932—although Kendall refused to say he had been left, since Thayer was first published by Kendall, but it was never an exclusive relationship; Sussman left him in 1933; Kendall reincorporated in 1934, left publishing, and was murdered under mysterious circumstances in 1937. Meanwhile, Sussman had teamed with Franklin Spier to form a firm that specialized in advertising books. Spier and Susan was closely connected to “The Saturday Review of Literature” and also to Bennet Cerf’s “Modern Library,” which Random House had purchased from Horace Liveright in 1925. Sussman’s approach was low-key, letting the books sells themselves—to what Cerf thought of as a “civilized minority”—emphasizing in the ads the reasonable sales price and the convenient size. In his memoirs, Cerf recollected, “Aaron has been invaluable to us,” handing basically the entire advertising load.

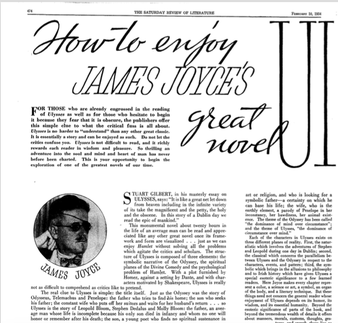

In 1934, Sussman had his most famous moment as an advertiser. Cert’s Random House had obtained the rights to James Joyce’s modernist classic, Ulysses. It became a huge seller, a breakthrough for Random House. Part of the reason for that was Sussman’s advertising acumen: his “How to Enjoy James Joyce’s Great Novel Ulysses,” which ran in the 10 February 1934 of “The Saturday Review of Literature” had been “hailed then and now as a landmark in the marketing of modernism to the general reading public,” according to literary historian Evan Brier. The ad included a chart of the book’s actions and a map, but was at pains to make clear that the book was approachable. Sussman digested each of the chapters for the readers, and noted that some would find in the book various references and other matters highfalutin, but for the average reader the book would be enjoyable—an educated person could understand it and there was a puzzle to be solved. Worry not about its obscurity, he counseled, and enjoy the story.

As an aside, then, its quite possible to see in this moment—and in others throughout Sussman's career, that the line between high modernist literature and popular literature of the time was relatively thin: remember that James Blish was a fan of Ulysses and also a write roof pulp science fiction. And Charles Fort considered himself first and foremost a writer trying to solve writerly problems. When Colin Bennett or Leo Knuth compare Fort to Joyce and other modernists it is with good reason: Forteanism was a species of modernism, at least in its earliest incarnations, and so of course attracted those interested in other modernist writers (or the authors themselves) like Thayer—bewitched by Ezra Pound—Dreiser and Ben Hecht (who admittedly was more rooted in the the fin de cycle Decadence movement, at least on my reading). Thayer’s “Thirteen Men,” a bestseller, had Nietzschean echoes (as well as resonances from Max Stirner) that would recur in the post-surrealism turn to anarchism in the work of Henry Miller and other high modernists.

Amid all of this work, the Susan family expanded: in 1931, Aaron and Carolyn had a son, Leon. In February 1934, just as the ad in the “Saturday Review” appeared, the three of them took a vacation to Bermuda—perhaps Sussman was trying to relax after the marathon effort that would have gone into the writing of the advertisement. Perhaps he was waiting out any potential fall out. As expected, Aaron was no fan of censorship—“Despite the unquenchable prejudice to the contrary, no book has ever committed a crime,” he wrote, and praised a fellow Fortean (though in name only), the lawyer Morris Ernst who defended a number of books against censorship—but despite his beliefs, he may have been practical enough to recognize there might be repercussions, given the furor that had surrounded “Ulysses” to that point. Work might have been exhausting, full stop, without regards to the ad, as well. A much, much later account of his work practices noted that he had to clear some advertising copy with the authors; used outside readers to evaluate the books he advertised; and inserted himself into the editorial process, if he felt it necessary. Perhaps he used some of these same techniques, if only in rudimentary form in the 1930s, as well. Among the other projects with which he was involved, he prompted psychiatrist David Seabird to publish “The Art of Selfishness,” a self-help manual for stopping all of lives petty tyrants from taking too much of each person’s time and energy.

In 1940, the Sussmans were living on 164th Place in Queens. They owned their home, worth $6,000—so the family was doing well. Carolyn was not employed outside the home, but was raising Leon, then 9. (Given that she worked as a teenager and never finished high school—only the first year—one wonders if she was relieved not to be eking out a living, or if she continued to do other jobs outside the home.) Her sister was living with them, Marie, and had been at least since 1935. Professionally, she was a sales lady (and like her sister never finished high school, going only two years), but had been unemployed for 104 weeks: the depression could still be felt.

In March 1944, Sussman left Spier&Sussman and, with Samuel Sugar, formed Sussman & Sugar, which specialized in books, although, as Sussman put it, what they sold were the contents, not the books themselves. In 1945, as part of a post-War expansion “Saturday Review” opened itself to general advertising; Sussman& Sugar were the account managers. Also during the 1940s Sussman was involved with “Books for Victory,” which donated books to soldiers at war. In the late 1940s, Sussman & Sugar were winning advertising awards for the work they did with Random House and Grosset & Dunlap. Sussman also seems to have had an amateur interest in photography. In 1948, he revised Archie Frederick Collins’s "The Amateur Photographer's Handbook,” and would continue to put out various updated editions until his death. He also continued his interest in the occult; having been moved by Ouspensky’s “Tertium Organum” and “A New Model of the Universe,” he was ecstatic when his “Strange Life of Ivan Osokin,” appeared in 1947.

The 1950s were a consequential era for Sussman and his firm, as they became wrapped up in the various obscenity trials of the time—and he helped to sell another notorious book. In 1956, Grace Metalious published “Peyton Place,” a book about the ribald sex that hid beneath the facade of a quiet American suburb. Sussman was instrumental in selling the book—indeed, according to (another) legend, it was Sussan who suggested the name, instead of the original “The Tree and the Blossom.” The book has been seen as the beginning of the end in American publishing, a novel that opened the floodgates to increasingly sordid stories. Of course, such stories were the stuff of modernism—Dreiser’s own novels dwelt on sex, and Nabokov’s Lolita appeared that same year. D. H. Lawrence’s novels had similarly made hearts flutter and censors anxious—as Sussman knew. He was responsible for advertising “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” put out by Grove in 1957, which prompted an obscenity trial. Again, the line between modernist high brow literature and middle brow books was so thin as to be invisible, at least from the perspective of the audience. (There are obviously aesthetic differences.) Sussman recognized the value of the salacious: as early as 1949, he was calling books such as these “breast sellers.” Banning books, he joked, would be the best way to get them read.

More books would follow over the decades, hundreds of them. A few stand out. Sussman & Sugar handled David Ogilvy’s 1964 “Confessions of an Advertising Man,” a bit of meta-advertising. He wrote an introduction to a new edition of Alexandra David-Neel’s book on Tibet. He wrote the foreword to a revised version Seabury’s 1937 “The Art of Selfishness.” It was put out by Julian Messner. With Ruth Goode, he wrote “The Magic of Walking.”

Aaron Sussman died 10 August 1991—the same month as Thayer, as it happened, but thirty-two years later. He was 87.

********

Obviously, there were many opportunities for Sussman to discover Charles Fort. He was a teenager when Fort’s first book appeared. A few years later, he was working for Horace Liveright, who had published Fort’s two books—although Fort wouldn’t publish again for several years, and then with a different publisher. I cannot reconstruct Sussman’s reading interests, but he did seem to have a developed interest in the esoteric, and that, too, could have led him to Fort. There’s also the possibility that he met Fort through Tiffany Thayer himself.

Thayer corresponded with Fort from Chicago beginning in the mid-1920s. He moved to New York as early as 1929—and was being acclaimed in his hometown Illinois newspaper for publishing a mystery thriller in a pulp magazine—and was at work with Literary Guild n its advertising department by 1930. He went to Fort’s house in April 1930, where they finally met face-to-face. At the same time, he would have been working with Sussman. His first novel, the innovatively structured “Thirteen Men,” appeared on bookstore shelves in May 1930. Sussman and Thayer became fast friends—one of Thayer’s few genuine friends, it would seem. Much later, Sussman would remember visiting Fort’s apartment, too, in that same year. He was impressed by him as both an innocent, tender to his wife, and a great mind, withdrawn from the world.

By that point, Fort was on the verge of publishing his third book of anomalies, this one to be put out by Sussman and Kendall. As he would with Peyton’s Place, Sussman suggested a title for the book, not happy with Fort’s “Skyward Ho!”: he thought “God is an Idiot” a better choice, Fort suggested variations on “The Time Has Come,” referring to a recurring theme in the book that inventions come when the time is right. (Everyone knew about steam for centuries, but it wasn’t time for the steam engine until the nineteenth century.) Fort also suggested “God and the Fishmonger” as an alternative. Thayer’s advice was “Lo!,” a mocking reference to astronomers’s constant ejaculation: “Lo! There is a star.” (I think “God and the Fishmonger the best of them but) Kendall, Sussman, and Fort agreed with Thayer and thus was named Fort’s book.

Sussman seems to have been anxious to get some good press for “Lo!” Fort’s second book, “New Lands,” had more or less tanked, and then he hadn’t published anything for some six years. Kendall’s company contacted Dreiser in the summer—he had taken a 10,000 mile trip across the country, returning in July—asking for opinions that could be used in selling “Lo!”: “To think that should be necessary,” Dreiser wrote to Fort, “or even seem so. You—the most fascinating literary figure since Poe. You—who for al I know may be the proprietor of an entirely new world viewpoint: You whose books thrill and astound me as almost no other books have thrilled and astounded me. And you write at once so authoritatively and delightfully. Well, such is Life[.] But, then, what shall I say? This? Or more than this? Shall I emphasize that yours is one of the master minds and temperaments of the world today? It is.” In preparation for the advertising of “Lo!” sent copies of “Book of the Damned” and “New Lands” to influential critics in November: Walter Yust and Joseph Henry Jackson received copies. So did his friends Edward McDonald, John Cowper Powys, and Harry Elmer Barnes. All three became fans, the final two signing up for the Fortean Society. (Indeed, in December, Powys met with Dreiser and Edgar Lee Master, and they “talked of Charles Fort and his queer ideas about other beings.”)

Thayer had been absent for some of this early planning, as he went to France for a time after the publication of “Thirteen Men,” but by December was helping planning a publicity campaign for “Lo!”—remember, both Thayer and Sussman were in the advertising business. Prompted by the newspaper publisher J. David Stern (who had suggested the same idea after the publication of “the Book of the Damned”), Thayer decided to launch the Fortean Society. Sussman was instrumental in its founding and spreading word of all the literary luminaries who were coming together to support Fort: Ben Hecht (the first Fortean), Stern, Thayer, Sussman himself, Booth Tarkington—who wrote the foreword to “New Lands”—Alexander Woollcott, Powys, Masters, and Dreiser, who was named the president.

Stories about the imminent founding of the Society started to appear in December, the first one I now of in Stern’s Philadelphia Record. The point, the article said, was to express skepticism of science and draw attention to physical anomalies. The article pointed, in particular, to inexplicable—and deadly—fogs that settled over London and Belgium that month. (This reference may have been prompted by Powys, who early in December read of the fogs and immediately thought of Fort.)

Publisher’s Weekly had a story on the coming of the Fortean Society in January of 1931, based on that story in the Record. The New York World announced the coming of the Fortean Society in its 21 January issue (and would be out of business in a month). That same day, Sussman was sending form letters announcing the first meeting of the Fortean Society. “reporters and photographers will be admitted for a short while during the meeting,” the letters said, tantalizing journalists about what might go on the rest of the time. Meanwhile, Thayer had drawn up Fortean Society letterhead and announced the Society was headquartered at 18 West 38th. The first—and only—meeting was held 26 January 1931, in J. David Stern’s apartment at the Savoy-Plaza hotel. An account of the evening was published in the “New York Post”—too be taken over by Stern in a couple of years—the next day. A digest of the transactions was put together as a pamphlet.

The publicity seemed to have helped—and was necessary. H. G. Wells's encomium to science “The Science of Life” was being published at the same time, with 20,000 copies planned, 10 each for a trade edition and a subscription edition. It was the antithesis of Fort, and threatened to attract all the attention. But Fort got notice, too—possibly in part because of the cover, which printed extollations from Dreiser (the sentence comparing him to Poe), Tarkington, Harry Elmer Barnes, Benjamin de Casseres, Powys, and Hecht There was an advertisement for “Lo!” in the 31 January Publisher’s Weekly (the day after Wells’s book was officially released). Time magazine referenced him on 9 February. Harry Hansen published a 600 word review of the book in The New York World on 13 February and Publisher’s Weekly reviewed it—kind of—the next day. On the 15th, Fortean Burton Rascoe offered his review in the New York Herald. Time offered a formal review on the 23rd. Monroe Upton did a radio review on the 25th. March 1st saw (Fortean) Maynard Shipley heaping praise on the book in the New York Times (Fort’s first positive review in that newspapers). The New York Evening Post ran a review the 14th of that month; the Boston Transcript on the 18th. There would be more sparse coverage throughout the beginning of the year. According to the not always reliable Sam Moskowitz, “Lo!” went through three printings in its first six weeks which, if correct, makes it far and away his best selling book. (Wells, though, having received Dreiser’s package of Fort’s books, was so disgusted by what he read he would not even crack open “Lo!”)

There were plans for a second meeting. In March 1931, Martin Kamin, a New York City bookstore owner—and also a member of the so-called “Lost Generation,” who would publish “Contact: A Quarterly Review,” with William Carlos Williams, the modernist poet—wrote Sussman advising him on advertising in Publisher’s Weekly, requesting 10 more copies of “Lo!”, and asking for display material to support another Fortean Society meeting. It was scheduled for the 27th but, for whatever reason, wasn’t held. Which seemed to be the end of the Society altogether. If there were any doubts, they would have been erased the following year. Kendall and Sussman put out Fort’s last book in the spring of 1932; the book got some publicity, but there was no party this time. Fort died in May, having seen a prepublication copy. Deeply saddened by Fort’s death, Dreiser left New York City. Thayer left New York City, too, taking a job with Paramount Studios in Hollywood, and then made a name for himself as a writer of salacious best-sellers. Not long after, Sussman left Kendall. Meanwhile, the British publisher Victor Gollancz declined to bring out an edition of “Wild Talents” in that country.

Fort had not completely dropped out of the public eye—there were passing references in both the mainstream press and little magazines and, in 1934, the science fiction pulp “Astounding Stories” serialized “Lo!” Sussman and Thayer also remained in some kind of contact—as Thayer was being sued for breach of contract for the sale of his “The Illustrious Corpse,” and Sussman wrote a couple of supporting affidavits, it seems likely that they were in some kind of contact. The two shared not only a vocation—advertising—but an overlapping sense of humor: Thayer was mordant and critical of the mis-use of language, for instance, and Sussman had a similar touch. Once he remembered being struck by a subway car advertisement: “Don’t cough till you’re blue in the face.” It was the kind of double-entendre that would have amused and infuriated Thayer.

In 1935, Thayer was contemplating reviving the moribund Society, though it would be a long process. Dreiser was decidedly not on board: Thayer had absconded with Fort’s notes, much to Dreiser’s chagrin, leaving him in no mood to collaborate. Indeed, he considered suing Thayer for the return of the notes; while exploring the possibility, other former Forteans were contacted, almost all of whom thought the Society was either a one-off event or had been permanently shuttered. (Only Powys was dismayed to hear that the Society had not continued.) Several dismissed their involvement entirely. But by 1937, Thayer was back in New York—back in advertising—and ready to re-start the Society. A few Founders were willing to work with him, at least nominally, among them Stern and Hecht. reading between the lines, only Sussman was enthusiastic. In September of 1937, the first issue of “The Fortean” appeared, and it attracted attention—Thayer’s lead article claim that dogmatic science had killed Amelia Earhart by falsely assuring her the geography of the earth was known. Thayer was an ad man and knew that controversy brought eyeballs—but Booth Tarkington and Harry Leon Wilson, at least, two Founders who had their name attached to the magazine were dismayed at what Thayer was up to, blindsided. Sussman seemed to be on good terms with Thayer, though. As the first issue was mailed out, Thayer wrote an acquaintance that he could get his book published by Julian Messner, whose advertising was then being handled by Sussman: “A Fortean, my good friend, and the man who did as well for my own Thirteen Men and a little thing called [the runaway bestseller] “Anthony Adverse” by someone named Macy or Owens [Hervey Allen] or something like that.”

It requires some speculation—though not a lot—to see what would have kept Sussman attached to the Fortean Society during the first years of its second iteration: there’s the friendship with Thayer, the interest in the occult, and, likely, a fascination with Fort as a generator of ideas. Introducing the revised version of Seabury's book in 1964, Sussman wrote, “Ideas are magical. They lurk in the strangest places, and often the simplest of them can transform all life around them. Benjamin Franklin sent up a kite; a French painter thought it might be nice if he could only capture on paper the picture his eyes could see; Einstein had the curious notion that light somehow was bent as it travelled through space—and the lives of untold millions were each affected personally by these ideas as though someone had reached out and touched them directly. Sometimes an idea can catch you at a crucial moment in your own life and jolt you out of a tailspin.” The foreword made no reference to Fort, but one feels his presence throughout those sentences—Sussman was a man intrigued by new ways of thinking, and Fort offered that.

But Sussman’s ideas about Fort and Forteanism were different than Thayer’s, and even as Sussman offered support—even silent support—to reviving the moribund Fortean Society, trouble awaited. The first glimmers of what would become a full blow out showed in 1940. Thayer had finally gotten around the compiling Fort’s four books on anomalies into a single omnibus edition—it took time for him just to gather complete copies of the four books, as some of the volumes were—in the words of Publisher’s Weekly— “almost impossible to find. Books had been swiped from the collections of Aaron Sussman, William Sloane, Ray Healey and other Fort enthusiasts and it took months of advertising to get all four volumes together.” Henry Holt was going to produce the books, and distribute them, while the Fortean Society would be listed as the official publisher. On 19 November, Sloane (who was seeing the book through the publication process) wrote Sussman, frustrated by Thayer and looking for someone to reign him in:

“I am sending you up Tiffany Thayer’s introduction for a quick glance before I write to him. Several things about this I think require a tactful hand. First of all no matter what Mr. Thayer thinks he cannot come out with all these extremely arbitrary statements about schools and churches unless he does it in such a way that our college and high school departments will not be on my neck for printing a thing of this sort. Secondly this introduction doesn’t do for Charles Fort enough of what should be done. Most of the best material in it comes from the middle onward and I would like to see a good deal more about Fort himself. I believe that if we want to get some good consideration of this book it is important to have the preface contain everything which can be reasonably said about Fort, since it is not likely that anyone is going to do a full length biography of him in the future. Do look this over again and give me a more detailed report than your telephone conversation about your own reaction to it. Think, too, about our other departments here. I’ll then write Thayer.”

Sussman, who was involved with advertising the book, must have prevailed upon Thayer to tone down the introduction, at least somewhat. It still started out—in a very Hechtian way—with a list of readers who probably should set the book aside, and praised atheism, but there was a substantial amount on Fort as a person and a thinker, and Thayer called out those he disagreed with in relatively vague terms. Holt’s textbook division was apparently appeased. And the book received solid advertising, especially in the Saturday Review, with its connections to Sussman. Hecht, too, reviewed it. (Not all Forteans were happy, though, and the science fiction Anthony Boucher compared it unfavorably to the true Forteanism that Thayer displayed in his introduction to “Lo!”)

The threads connecting Thayer to the other Founders—and many Forteans—continued to fray through the early 1940s, as he staked out political positions in The Fortean that opposed the military and blamed the war on a cadre of politicians and businessmen. The February 1942 issue—number 6—included a long article called “Circus Day is Over” that irritated J. David Stern, Alexander Woollcott, Ben Hecht, and Booth Tarkington—to the point that Stern reported Thayer to the FBI for spreading sedition. Sussman was involved with “Books for Victory,” but there’s no evidence that he complained at the time; or perhaps he just didn't see it when the magazine first came appeared. At any rate, the next issue, which came out more than a year later, in June 1943, saw Thayer not backing down. His “The Socratic Method” led off the issue, a series of pointed questions that pushed the reader to conclude that the war was orchestrated by the rich and powerful. This time, Russell Maloney, a Fortean with the New Yorker, reported Thayer to the FBI.

Also this time, Sussman was among those going apoplectic over Thayer’s sedition. On 23 July 1943, Sussman wrote Thayer, “I have just read the June 1943 issue of the Fortean Society Magazine, and I am disgusted. You are perverting what I believe to be the real and only business of the Society--which is, I have always assumed, the spreading of word about Charles Fort, his ideas and his books. I’m sure that had Fort seen your latest two issues he would have expired from shock. What you are doing, unfortunately, under the guise of publicizing him, is making his name a synonym for the dirtiest kind of subversive business. As Secretary of the Society you have an obligation to the rest of the members which you have refused to accept. Since we cannot control what you say in the magazine--and since you insist on promoting Thayer and his ideas, instead of Fort and his ideas--you leave us no alternative but to get out. Please accept this, therefore, as my resignation, to take effect at once--and do not use my name in connection with the work of the Society hereafter. I would appreciate an acknowledgment of this letter.”

That stung Thayer. He could deal with criticism from Stern and Tarkington (who seems to have been relatively genial in his approach); Hecht and Woollcott didn’t bother him too much and, indeed, he would tolerate a lot of divergent opinions from Hecht without changing his own tune. But Sussman was a close friend and, in a rare event for Thayer, who didn’t take disagreement as a cause for a break—he otherwise seems to have split with a number of previous friends, continually turning his back on people he had once championed. (Ezra Pound was another friend he did not break up with.) Eight days later, Thayer replied, “This will acknowledge receipt of your letter dated July 23, 1943, containing your resignation from the Fortean Society. Your protest puts me in a quandary, since your sympathy and active cooperation with the work of the Society is valued very highly. I trust that if our critical attitude toward current political events disappeared at once from the Magazine that you would reconsider your decision. Is that true?”

I have not seen a response from Sussman, but clearly the answer was yes: for Thayer modulated his criticism, and Sussman continued to belong to the Fortean Society. The next issue of the magazine appeared in December 1943 and had little of the previous political vitriol, and what was there was often indirect: for example, it was the issue that Thayer praised Harry Leon Wilson as one of the Society’s Founders—though Wilson had almost nothing to do with the Society, and little to say about Fort at all—probably because Wilson’s son, Leon, had been arrested for refusing to be drafted int the war. The Spring 1944 issue (#9) advertised the writings of conscientious objectors, but also spent an inordinate amount of space on astrology and the Drayson problem; no provocative essays. Again, issue 10, summer of 1944, focused on the anomalous—with some references to the sad state of schools and praise for Scott Nearing. Sussman’s name continued to appear on Fortean Society letterhead and in publicity packets, such as “The Fortean Society is the Red Cross of the Human Mind,” which certainly had a political slant—anarchist, left-libertarian—but avoided the striking language of Thayer’s earlier columns.

I’m not sure why, but Sussman does not seem to have been active with the Society in the five years after his argument with Thayer. Perhaps there was still some bad blood. Perhaps he was simply too busy. Perhaps he was being cautious. I just don’t know. But aside from Thayer name-checking him in his publicity for the Society and magazine, now renamed Doubt, starting with issue 11, Sussman’s name never appeared. Nor did Thayer ever dedicate a column to him as a Founder, though he did even to those who had decidedly broke with him, such as Dreiser and Woollcott. I’m not sure why that is, either. Perhaps Sussman asked not to be written up. Perhaps Thayer lost interest in the series on the Founders—but then why skip Sussman, his closest friend among that group? It remains a mystery.

His name started to appear as a contributor in issue 16, January 1947. Eleven more times through 1956 his name appeared in Doubt, further defining his ideas about Fort and Forteanism.

What comes through clearest in the material Sussman sent to Thayer is that, despite their disagreements and Thayer’s extreme political views, the two men were actually simpatico on social and political issues, at least many of them, both suspicious not just of science but of the powers-that-be more generally. Including God: Sussman’s first credited submission was an old report, from June 1935, about more than 300 Mexican supplicants who prayed for rain only to be drowned by a sudden cloudburst; those that survived did so by climbing upon the dead bodies of their fellow parishioners. Thayer included the story with several other similarly themed stories under the ironic title “Hooray for God!” Sussman’s next contribution, in the following issue, was suspicious of both the news and the military—it concerned the development of a death ray that had been used to kill a sparrow and might be used during the next World War. The death ray was reported by Time in what Thayer called “the jocose, carefree style which Time employs to dispose of the petty concerns of the millions.” Not an attack on FDR, or a claim that World War II was orchestrated by the planet’s power-brokers, but not a ringing endorsement of the rapidly consolidating military-industrial complex, either.

By 1948, Sussman seems to have been fully recommitted to Thayer’s Fortean Society. His third contribution appeared in March 1948 (number 20) and referred to Fort’s favorite bête noir: astronomy, Life magazine had caught several different New York newspapers all reporting on a comet giving different numbers of tails behind the astronomical body, two, three, four, or six depending upon the publication. The article also provided support for Thayer’s distrust of the press—or what he called, borrowing a term from Ezra Pound, the wypers. Later in the year, as Thayer was playing around the idea of a Fortean University—what he unsubtly codenamed F.U.—Sussman kicked in $25 toward the cause; the support—but not the amount—made issue 21. Two issues later, in December 1948, Sussman was credited among many, many other with contributing information on the story of Wonet, the Fortean cause célèbre, strongly suggesting that Sussman was paying close attention to Thayer and his Society.

Sussman appeared twice in 1949, both in issue 24 (April) on pages 364 and 365, displaying both his contempt for authority and a mordant humor (that may have bled into a belief in the occult). The first story he sent in concerned a new feed for hogs, cattle, and poultry that was showing promise. It was 50% molasses—and comically-treated sawdust. “End result, more cancer?,” Sussman asked. Other Forteans, particularly Thayer and Russell, were similarly concerned with the industrialization of the food supply. On the next page of the magazine was a story about Jake Bird. Thayer did not report Sussman’s comments—if any—so it is necessary to speculate. The article was about Jake Bird, who had been sentenced to die for murder, but predicted his enemies would be there at the pearly gates to greet him: and, indeed, before he was executed, a number of police, prosecutors, and court employees involved in his case had died. There’s a black humor inherent in the story—at the expense of authorities—and also the possibility of some occult powers, either the ability to see the future or some Wild Talent that allowed Bird to kill his accusers from afar. Sussman’s exact interest is unclear, and may have been in both aspects.

The ad man continued his connection with the Fortean Society into the 1950s, though his interest and understanding of Forteanism is impossible to track—whether it had evolved or not is unknown. Thayer’s references are just too vague. The only one of any substance is the first of the decade, in Doubt 29, July 1950. Thayer hosted a dinner for Garry Davis, to see if he would accept a Fellowship with the Fortean Society. (Thayer had earlier sent him a letter asking, and Thayer had responded that he wasn’t clear what Forteans were.) Among those at the dinner were Scott Nearing, J. M. Scandrett, the endocrinologist Harry Benjamin, actor Fred Keating, and Sussman. This very different meeting of the Fortean Society—echoing the one from almost 20 years before, but with an almost entirely different cast and intention—was also not meant for publicity: Thayer pointedly said that the press had not been invited.

Sussman’s name appeared four more times in Doubt, 36 (April 1952), 43 (February 1954), 45 (July 1954), and 52 (May 1956). These were generic credits, though, without Thayer correlating them to specific contributions, so it is impossible to say what Sussman contributed. Worth noting, though, is that he seemed to be drifting away, like so many other Forteans who were enthusiastic during the 1940s but did not continue through the decadal transition. Four contributions in four years is not many, and there’s not a single reference to Sussman in the final three years of the Society. The constellation of emotions and fears that motivated Sussman in the 1930s and, especially the 1940s—when he voluntarily came back to the Society, with no need to advertise Fort—had dissipated. Although Sussman would remain interested in esoteric literature at least into the 1960s, his Forteanism seems to have wavered, or, at least, was no longer on public display. I cannot find him making any reference to Fort after the 1950s, with he single exception of answering Damon Knight’s questions about Fort, Forteanism, and Thayer for Knight’s biography of Fort.

By his own account, Sussman started in the publishing business first with G. P. Putnam’s Sons, and then with Horace Liveright, Inc.—note that it was Boni & Liveright which published Charles Fort’s first two books—doing editorial and promotional chores. In April 1930, he became a partner in Claude Kendall’s publishing venture (although the name of the firm did not change). Kendall was an interesting character, about whom little has been written. He worked for the United Press in Argentina for a time, before returning to the States and opening his own publishing business. He was a provocateur. His first book was “Uncle Sham," an attack on the United States by Indian writer Kanhayalal Gauba. (There's a Fortean connection here, as for years Thayer’s would run in Doubt excerpts of Gauba’s “The Pathology of Princes” under the title “The Truth about India.”) With Sussman, Kendall published Russian writer Andre Sobol’s collecion “Freak Show,” Octave Mirbeau’s sado-masochistic “Torture Garden” (translated by Alvah Bessie, whom Susan may have known as a younger man), the banned-in-Canada “Twisted Clay,” and Alexandra David-Neel’s esoteric classic—which would become a touch-point in the Shaver mystery of the 1940s—“Magic and Mystery in Tibet.” He tried to obtain the rights to the sure-to-be-censored “Ulysses,” by James Joyce. The second book they put out was Thayer's first novel “Thirteen Men,” and Kendall, at least, would publish three others Thayer novels, “Call Her Savage,” “Thirteen Men,” and “An American Girl.” (Sussman declined Thayer’s “The Illustrious Corpse,” thinking it would sell better as a more cheaply priced book; the subsequent publication of that novel got Thayer in legal trouble, and Sussman was dragged into it.) Of course, Kendall also published Fort’s last two books—Sussman designed both.

Thayer left Kendall in 1932—although Kendall refused to say he had been left, since Thayer was first published by Kendall, but it was never an exclusive relationship; Sussman left him in 1933; Kendall reincorporated in 1934, left publishing, and was murdered under mysterious circumstances in 1937. Meanwhile, Sussman had teamed with Franklin Spier to form a firm that specialized in advertising books. Spier and Susan was closely connected to “The Saturday Review of Literature” and also to Bennet Cerf’s “Modern Library,” which Random House had purchased from Horace Liveright in 1925. Sussman’s approach was low-key, letting the books sells themselves—to what Cerf thought of as a “civilized minority”—emphasizing in the ads the reasonable sales price and the convenient size. In his memoirs, Cerf recollected, “Aaron has been invaluable to us,” handing basically the entire advertising load.

In 1934, Sussman had his most famous moment as an advertiser. Cert’s Random House had obtained the rights to James Joyce’s modernist classic, Ulysses. It became a huge seller, a breakthrough for Random House. Part of the reason for that was Sussman’s advertising acumen: his “How to Enjoy James Joyce’s Great Novel Ulysses,” which ran in the 10 February 1934 of “The Saturday Review of Literature” had been “hailed then and now as a landmark in the marketing of modernism to the general reading public,” according to literary historian Evan Brier. The ad included a chart of the book’s actions and a map, but was at pains to make clear that the book was approachable. Sussman digested each of the chapters for the readers, and noted that some would find in the book various references and other matters highfalutin, but for the average reader the book would be enjoyable—an educated person could understand it and there was a puzzle to be solved. Worry not about its obscurity, he counseled, and enjoy the story.

As an aside, then, its quite possible to see in this moment—and in others throughout Sussman's career, that the line between high modernist literature and popular literature of the time was relatively thin: remember that James Blish was a fan of Ulysses and also a write roof pulp science fiction. And Charles Fort considered himself first and foremost a writer trying to solve writerly problems. When Colin Bennett or Leo Knuth compare Fort to Joyce and other modernists it is with good reason: Forteanism was a species of modernism, at least in its earliest incarnations, and so of course attracted those interested in other modernist writers (or the authors themselves) like Thayer—bewitched by Ezra Pound—Dreiser and Ben Hecht (who admittedly was more rooted in the the fin de cycle Decadence movement, at least on my reading). Thayer’s “Thirteen Men,” a bestseller, had Nietzschean echoes (as well as resonances from Max Stirner) that would recur in the post-surrealism turn to anarchism in the work of Henry Miller and other high modernists.

Amid all of this work, the Susan family expanded: in 1931, Aaron and Carolyn had a son, Leon. In February 1934, just as the ad in the “Saturday Review” appeared, the three of them took a vacation to Bermuda—perhaps Sussman was trying to relax after the marathon effort that would have gone into the writing of the advertisement. Perhaps he was waiting out any potential fall out. As expected, Aaron was no fan of censorship—“Despite the unquenchable prejudice to the contrary, no book has ever committed a crime,” he wrote, and praised a fellow Fortean (though in name only), the lawyer Morris Ernst who defended a number of books against censorship—but despite his beliefs, he may have been practical enough to recognize there might be repercussions, given the furor that had surrounded “Ulysses” to that point. Work might have been exhausting, full stop, without regards to the ad, as well. A much, much later account of his work practices noted that he had to clear some advertising copy with the authors; used outside readers to evaluate the books he advertised; and inserted himself into the editorial process, if he felt it necessary. Perhaps he used some of these same techniques, if only in rudimentary form in the 1930s, as well. Among the other projects with which he was involved, he prompted psychiatrist David Seabird to publish “The Art of Selfishness,” a self-help manual for stopping all of lives petty tyrants from taking too much of each person’s time and energy.

In 1940, the Sussmans were living on 164th Place in Queens. They owned their home, worth $6,000—so the family was doing well. Carolyn was not employed outside the home, but was raising Leon, then 9. (Given that she worked as a teenager and never finished high school—only the first year—one wonders if she was relieved not to be eking out a living, or if she continued to do other jobs outside the home.) Her sister was living with them, Marie, and had been at least since 1935. Professionally, she was a sales lady (and like her sister never finished high school, going only two years), but had been unemployed for 104 weeks: the depression could still be felt.

In March 1944, Sussman left Spier&Sussman and, with Samuel Sugar, formed Sussman & Sugar, which specialized in books, although, as Sussman put it, what they sold were the contents, not the books themselves. In 1945, as part of a post-War expansion “Saturday Review” opened itself to general advertising; Sussman& Sugar were the account managers. Also during the 1940s Sussman was involved with “Books for Victory,” which donated books to soldiers at war. In the late 1940s, Sussman & Sugar were winning advertising awards for the work they did with Random House and Grosset & Dunlap. Sussman also seems to have had an amateur interest in photography. In 1948, he revised Archie Frederick Collins’s "The Amateur Photographer's Handbook,” and would continue to put out various updated editions until his death. He also continued his interest in the occult; having been moved by Ouspensky’s “Tertium Organum” and “A New Model of the Universe,” he was ecstatic when his “Strange Life of Ivan Osokin,” appeared in 1947.

The 1950s were a consequential era for Sussman and his firm, as they became wrapped up in the various obscenity trials of the time—and he helped to sell another notorious book. In 1956, Grace Metalious published “Peyton Place,” a book about the ribald sex that hid beneath the facade of a quiet American suburb. Sussman was instrumental in selling the book—indeed, according to (another) legend, it was Sussan who suggested the name, instead of the original “The Tree and the Blossom.” The book has been seen as the beginning of the end in American publishing, a novel that opened the floodgates to increasingly sordid stories. Of course, such stories were the stuff of modernism—Dreiser’s own novels dwelt on sex, and Nabokov’s Lolita appeared that same year. D. H. Lawrence’s novels had similarly made hearts flutter and censors anxious—as Sussman knew. He was responsible for advertising “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” put out by Grove in 1957, which prompted an obscenity trial. Again, the line between modernist high brow literature and middle brow books was so thin as to be invisible, at least from the perspective of the audience. (There are obviously aesthetic differences.) Sussman recognized the value of the salacious: as early as 1949, he was calling books such as these “breast sellers.” Banning books, he joked, would be the best way to get them read.

More books would follow over the decades, hundreds of them. A few stand out. Sussman & Sugar handled David Ogilvy’s 1964 “Confessions of an Advertising Man,” a bit of meta-advertising. He wrote an introduction to a new edition of Alexandra David-Neel’s book on Tibet. He wrote the foreword to a revised version Seabury’s 1937 “The Art of Selfishness.” It was put out by Julian Messner. With Ruth Goode, he wrote “The Magic of Walking.”

Aaron Sussman died 10 August 1991—the same month as Thayer, as it happened, but thirty-two years later. He was 87.

********

Obviously, there were many opportunities for Sussman to discover Charles Fort. He was a teenager when Fort’s first book appeared. A few years later, he was working for Horace Liveright, who had published Fort’s two books—although Fort wouldn’t publish again for several years, and then with a different publisher. I cannot reconstruct Sussman’s reading interests, but he did seem to have a developed interest in the esoteric, and that, too, could have led him to Fort. There’s also the possibility that he met Fort through Tiffany Thayer himself.

Thayer corresponded with Fort from Chicago beginning in the mid-1920s. He moved to New York as early as 1929—and was being acclaimed in his hometown Illinois newspaper for publishing a mystery thriller in a pulp magazine—and was at work with Literary Guild n its advertising department by 1930. He went to Fort’s house in April 1930, where they finally met face-to-face. At the same time, he would have been working with Sussman. His first novel, the innovatively structured “Thirteen Men,” appeared on bookstore shelves in May 1930. Sussman and Thayer became fast friends—one of Thayer’s few genuine friends, it would seem. Much later, Sussman would remember visiting Fort’s apartment, too, in that same year. He was impressed by him as both an innocent, tender to his wife, and a great mind, withdrawn from the world.

By that point, Fort was on the verge of publishing his third book of anomalies, this one to be put out by Sussman and Kendall. As he would with Peyton’s Place, Sussman suggested a title for the book, not happy with Fort’s “Skyward Ho!”: he thought “God is an Idiot” a better choice, Fort suggested variations on “The Time Has Come,” referring to a recurring theme in the book that inventions come when the time is right. (Everyone knew about steam for centuries, but it wasn’t time for the steam engine until the nineteenth century.) Fort also suggested “God and the Fishmonger” as an alternative. Thayer’s advice was “Lo!,” a mocking reference to astronomers’s constant ejaculation: “Lo! There is a star.” (I think “God and the Fishmonger the best of them but) Kendall, Sussman, and Fort agreed with Thayer and thus was named Fort’s book.

Sussman seems to have been anxious to get some good press for “Lo!” Fort’s second book, “New Lands,” had more or less tanked, and then he hadn’t published anything for some six years. Kendall’s company contacted Dreiser in the summer—he had taken a 10,000 mile trip across the country, returning in July—asking for opinions that could be used in selling “Lo!”: “To think that should be necessary,” Dreiser wrote to Fort, “or even seem so. You—the most fascinating literary figure since Poe. You—who for al I know may be the proprietor of an entirely new world viewpoint: You whose books thrill and astound me as almost no other books have thrilled and astounded me. And you write at once so authoritatively and delightfully. Well, such is Life[.] But, then, what shall I say? This? Or more than this? Shall I emphasize that yours is one of the master minds and temperaments of the world today? It is.” In preparation for the advertising of “Lo!” sent copies of “Book of the Damned” and “New Lands” to influential critics in November: Walter Yust and Joseph Henry Jackson received copies. So did his friends Edward McDonald, John Cowper Powys, and Harry Elmer Barnes. All three became fans, the final two signing up for the Fortean Society. (Indeed, in December, Powys met with Dreiser and Edgar Lee Master, and they “talked of Charles Fort and his queer ideas about other beings.”)

Thayer had been absent for some of this early planning, as he went to France for a time after the publication of “Thirteen Men,” but by December was helping planning a publicity campaign for “Lo!”—remember, both Thayer and Sussman were in the advertising business. Prompted by the newspaper publisher J. David Stern (who had suggested the same idea after the publication of “the Book of the Damned”), Thayer decided to launch the Fortean Society. Sussman was instrumental in its founding and spreading word of all the literary luminaries who were coming together to support Fort: Ben Hecht (the first Fortean), Stern, Thayer, Sussman himself, Booth Tarkington—who wrote the foreword to “New Lands”—Alexander Woollcott, Powys, Masters, and Dreiser, who was named the president.

Stories about the imminent founding of the Society started to appear in December, the first one I now of in Stern’s Philadelphia Record. The point, the article said, was to express skepticism of science and draw attention to physical anomalies. The article pointed, in particular, to inexplicable—and deadly—fogs that settled over London and Belgium that month. (This reference may have been prompted by Powys, who early in December read of the fogs and immediately thought of Fort.)

Publisher’s Weekly had a story on the coming of the Fortean Society in January of 1931, based on that story in the Record. The New York World announced the coming of the Fortean Society in its 21 January issue (and would be out of business in a month). That same day, Sussman was sending form letters announcing the first meeting of the Fortean Society. “reporters and photographers will be admitted for a short while during the meeting,” the letters said, tantalizing journalists about what might go on the rest of the time. Meanwhile, Thayer had drawn up Fortean Society letterhead and announced the Society was headquartered at 18 West 38th. The first—and only—meeting was held 26 January 1931, in J. David Stern’s apartment at the Savoy-Plaza hotel. An account of the evening was published in the “New York Post”—too be taken over by Stern in a couple of years—the next day. A digest of the transactions was put together as a pamphlet.

The publicity seemed to have helped—and was necessary. H. G. Wells's encomium to science “The Science of Life” was being published at the same time, with 20,000 copies planned, 10 each for a trade edition and a subscription edition. It was the antithesis of Fort, and threatened to attract all the attention. But Fort got notice, too—possibly in part because of the cover, which printed extollations from Dreiser (the sentence comparing him to Poe), Tarkington, Harry Elmer Barnes, Benjamin de Casseres, Powys, and Hecht There was an advertisement for “Lo!” in the 31 January Publisher’s Weekly (the day after Wells’s book was officially released). Time magazine referenced him on 9 February. Harry Hansen published a 600 word review of the book in The New York World on 13 February and Publisher’s Weekly reviewed it—kind of—the next day. On the 15th, Fortean Burton Rascoe offered his review in the New York Herald. Time offered a formal review on the 23rd. Monroe Upton did a radio review on the 25th. March 1st saw (Fortean) Maynard Shipley heaping praise on the book in the New York Times (Fort’s first positive review in that newspapers). The New York Evening Post ran a review the 14th of that month; the Boston Transcript on the 18th. There would be more sparse coverage throughout the beginning of the year. According to the not always reliable Sam Moskowitz, “Lo!” went through three printings in its first six weeks which, if correct, makes it far and away his best selling book. (Wells, though, having received Dreiser’s package of Fort’s books, was so disgusted by what he read he would not even crack open “Lo!”)

There were plans for a second meeting. In March 1931, Martin Kamin, a New York City bookstore owner—and also a member of the so-called “Lost Generation,” who would publish “Contact: A Quarterly Review,” with William Carlos Williams, the modernist poet—wrote Sussman advising him on advertising in Publisher’s Weekly, requesting 10 more copies of “Lo!”, and asking for display material to support another Fortean Society meeting. It was scheduled for the 27th but, for whatever reason, wasn’t held. Which seemed to be the end of the Society altogether. If there were any doubts, they would have been erased the following year. Kendall and Sussman put out Fort’s last book in the spring of 1932; the book got some publicity, but there was no party this time. Fort died in May, having seen a prepublication copy. Deeply saddened by Fort’s death, Dreiser left New York City. Thayer left New York City, too, taking a job with Paramount Studios in Hollywood, and then made a name for himself as a writer of salacious best-sellers. Not long after, Sussman left Kendall. Meanwhile, the British publisher Victor Gollancz declined to bring out an edition of “Wild Talents” in that country.

Fort had not completely dropped out of the public eye—there were passing references in both the mainstream press and little magazines and, in 1934, the science fiction pulp “Astounding Stories” serialized “Lo!” Sussman and Thayer also remained in some kind of contact—as Thayer was being sued for breach of contract for the sale of his “The Illustrious Corpse,” and Sussman wrote a couple of supporting affidavits, it seems likely that they were in some kind of contact. The two shared not only a vocation—advertising—but an overlapping sense of humor: Thayer was mordant and critical of the mis-use of language, for instance, and Sussman had a similar touch. Once he remembered being struck by a subway car advertisement: “Don’t cough till you’re blue in the face.” It was the kind of double-entendre that would have amused and infuriated Thayer.

In 1935, Thayer was contemplating reviving the moribund Society, though it would be a long process. Dreiser was decidedly not on board: Thayer had absconded with Fort’s notes, much to Dreiser’s chagrin, leaving him in no mood to collaborate. Indeed, he considered suing Thayer for the return of the notes; while exploring the possibility, other former Forteans were contacted, almost all of whom thought the Society was either a one-off event or had been permanently shuttered. (Only Powys was dismayed to hear that the Society had not continued.) Several dismissed their involvement entirely. But by 1937, Thayer was back in New York—back in advertising—and ready to re-start the Society. A few Founders were willing to work with him, at least nominally, among them Stern and Hecht. reading between the lines, only Sussman was enthusiastic. In September of 1937, the first issue of “The Fortean” appeared, and it attracted attention—Thayer’s lead article claim that dogmatic science had killed Amelia Earhart by falsely assuring her the geography of the earth was known. Thayer was an ad man and knew that controversy brought eyeballs—but Booth Tarkington and Harry Leon Wilson, at least, two Founders who had their name attached to the magazine were dismayed at what Thayer was up to, blindsided. Sussman seemed to be on good terms with Thayer, though. As the first issue was mailed out, Thayer wrote an acquaintance that he could get his book published by Julian Messner, whose advertising was then being handled by Sussman: “A Fortean, my good friend, and the man who did as well for my own Thirteen Men and a little thing called [the runaway bestseller] “Anthony Adverse” by someone named Macy or Owens [Hervey Allen] or something like that.”

It requires some speculation—though not a lot—to see what would have kept Sussman attached to the Fortean Society during the first years of its second iteration: there’s the friendship with Thayer, the interest in the occult, and, likely, a fascination with Fort as a generator of ideas. Introducing the revised version of Seabury's book in 1964, Sussman wrote, “Ideas are magical. They lurk in the strangest places, and often the simplest of them can transform all life around them. Benjamin Franklin sent up a kite; a French painter thought it might be nice if he could only capture on paper the picture his eyes could see; Einstein had the curious notion that light somehow was bent as it travelled through space—and the lives of untold millions were each affected personally by these ideas as though someone had reached out and touched them directly. Sometimes an idea can catch you at a crucial moment in your own life and jolt you out of a tailspin.” The foreword made no reference to Fort, but one feels his presence throughout those sentences—Sussman was a man intrigued by new ways of thinking, and Fort offered that.

But Sussman’s ideas about Fort and Forteanism were different than Thayer’s, and even as Sussman offered support—even silent support—to reviving the moribund Fortean Society, trouble awaited. The first glimmers of what would become a full blow out showed in 1940. Thayer had finally gotten around the compiling Fort’s four books on anomalies into a single omnibus edition—it took time for him just to gather complete copies of the four books, as some of the volumes were—in the words of Publisher’s Weekly— “almost impossible to find. Books had been swiped from the collections of Aaron Sussman, William Sloane, Ray Healey and other Fort enthusiasts and it took months of advertising to get all four volumes together.” Henry Holt was going to produce the books, and distribute them, while the Fortean Society would be listed as the official publisher. On 19 November, Sloane (who was seeing the book through the publication process) wrote Sussman, frustrated by Thayer and looking for someone to reign him in:

“I am sending you up Tiffany Thayer’s introduction for a quick glance before I write to him. Several things about this I think require a tactful hand. First of all no matter what Mr. Thayer thinks he cannot come out with all these extremely arbitrary statements about schools and churches unless he does it in such a way that our college and high school departments will not be on my neck for printing a thing of this sort. Secondly this introduction doesn’t do for Charles Fort enough of what should be done. Most of the best material in it comes from the middle onward and I would like to see a good deal more about Fort himself. I believe that if we want to get some good consideration of this book it is important to have the preface contain everything which can be reasonably said about Fort, since it is not likely that anyone is going to do a full length biography of him in the future. Do look this over again and give me a more detailed report than your telephone conversation about your own reaction to it. Think, too, about our other departments here. I’ll then write Thayer.”

Sussman, who was involved with advertising the book, must have prevailed upon Thayer to tone down the introduction, at least somewhat. It still started out—in a very Hechtian way—with a list of readers who probably should set the book aside, and praised atheism, but there was a substantial amount on Fort as a person and a thinker, and Thayer called out those he disagreed with in relatively vague terms. Holt’s textbook division was apparently appeased. And the book received solid advertising, especially in the Saturday Review, with its connections to Sussman. Hecht, too, reviewed it. (Not all Forteans were happy, though, and the science fiction Anthony Boucher compared it unfavorably to the true Forteanism that Thayer displayed in his introduction to “Lo!”)

The threads connecting Thayer to the other Founders—and many Forteans—continued to fray through the early 1940s, as he staked out political positions in The Fortean that opposed the military and blamed the war on a cadre of politicians and businessmen. The February 1942 issue—number 6—included a long article called “Circus Day is Over” that irritated J. David Stern, Alexander Woollcott, Ben Hecht, and Booth Tarkington—to the point that Stern reported Thayer to the FBI for spreading sedition. Sussman was involved with “Books for Victory,” but there’s no evidence that he complained at the time; or perhaps he just didn't see it when the magazine first came appeared. At any rate, the next issue, which came out more than a year later, in June 1943, saw Thayer not backing down. His “The Socratic Method” led off the issue, a series of pointed questions that pushed the reader to conclude that the war was orchestrated by the rich and powerful. This time, Russell Maloney, a Fortean with the New Yorker, reported Thayer to the FBI.

Also this time, Sussman was among those going apoplectic over Thayer’s sedition. On 23 July 1943, Sussman wrote Thayer, “I have just read the June 1943 issue of the Fortean Society Magazine, and I am disgusted. You are perverting what I believe to be the real and only business of the Society--which is, I have always assumed, the spreading of word about Charles Fort, his ideas and his books. I’m sure that had Fort seen your latest two issues he would have expired from shock. What you are doing, unfortunately, under the guise of publicizing him, is making his name a synonym for the dirtiest kind of subversive business. As Secretary of the Society you have an obligation to the rest of the members which you have refused to accept. Since we cannot control what you say in the magazine--and since you insist on promoting Thayer and his ideas, instead of Fort and his ideas--you leave us no alternative but to get out. Please accept this, therefore, as my resignation, to take effect at once--and do not use my name in connection with the work of the Society hereafter. I would appreciate an acknowledgment of this letter.”

That stung Thayer. He could deal with criticism from Stern and Tarkington (who seems to have been relatively genial in his approach); Hecht and Woollcott didn’t bother him too much and, indeed, he would tolerate a lot of divergent opinions from Hecht without changing his own tune. But Sussman was a close friend and, in a rare event for Thayer, who didn’t take disagreement as a cause for a break—he otherwise seems to have split with a number of previous friends, continually turning his back on people he had once championed. (Ezra Pound was another friend he did not break up with.) Eight days later, Thayer replied, “This will acknowledge receipt of your letter dated July 23, 1943, containing your resignation from the Fortean Society. Your protest puts me in a quandary, since your sympathy and active cooperation with the work of the Society is valued very highly. I trust that if our critical attitude toward current political events disappeared at once from the Magazine that you would reconsider your decision. Is that true?”

I have not seen a response from Sussman, but clearly the answer was yes: for Thayer modulated his criticism, and Sussman continued to belong to the Fortean Society. The next issue of the magazine appeared in December 1943 and had little of the previous political vitriol, and what was there was often indirect: for example, it was the issue that Thayer praised Harry Leon Wilson as one of the Society’s Founders—though Wilson had almost nothing to do with the Society, and little to say about Fort at all—probably because Wilson’s son, Leon, had been arrested for refusing to be drafted int the war. The Spring 1944 issue (#9) advertised the writings of conscientious objectors, but also spent an inordinate amount of space on astrology and the Drayson problem; no provocative essays. Again, issue 10, summer of 1944, focused on the anomalous—with some references to the sad state of schools and praise for Scott Nearing. Sussman’s name continued to appear on Fortean Society letterhead and in publicity packets, such as “The Fortean Society is the Red Cross of the Human Mind,” which certainly had a political slant—anarchist, left-libertarian—but avoided the striking language of Thayer’s earlier columns.

I’m not sure why, but Sussman does not seem to have been active with the Society in the five years after his argument with Thayer. Perhaps there was still some bad blood. Perhaps he was simply too busy. Perhaps he was being cautious. I just don’t know. But aside from Thayer name-checking him in his publicity for the Society and magazine, now renamed Doubt, starting with issue 11, Sussman’s name never appeared. Nor did Thayer ever dedicate a column to him as a Founder, though he did even to those who had decidedly broke with him, such as Dreiser and Woollcott. I’m not sure why that is, either. Perhaps Sussman asked not to be written up. Perhaps Thayer lost interest in the series on the Founders—but then why skip Sussman, his closest friend among that group? It remains a mystery.

His name started to appear as a contributor in issue 16, January 1947. Eleven more times through 1956 his name appeared in Doubt, further defining his ideas about Fort and Forteanism.

What comes through clearest in the material Sussman sent to Thayer is that, despite their disagreements and Thayer’s extreme political views, the two men were actually simpatico on social and political issues, at least many of them, both suspicious not just of science but of the powers-that-be more generally. Including God: Sussman’s first credited submission was an old report, from June 1935, about more than 300 Mexican supplicants who prayed for rain only to be drowned by a sudden cloudburst; those that survived did so by climbing upon the dead bodies of their fellow parishioners. Thayer included the story with several other similarly themed stories under the ironic title “Hooray for God!” Sussman’s next contribution, in the following issue, was suspicious of both the news and the military—it concerned the development of a death ray that had been used to kill a sparrow and might be used during the next World War. The death ray was reported by Time in what Thayer called “the jocose, carefree style which Time employs to dispose of the petty concerns of the millions.” Not an attack on FDR, or a claim that World War II was orchestrated by the planet’s power-brokers, but not a ringing endorsement of the rapidly consolidating military-industrial complex, either.

By 1948, Sussman seems to have been fully recommitted to Thayer’s Fortean Society. His third contribution appeared in March 1948 (number 20) and referred to Fort’s favorite bête noir: astronomy, Life magazine had caught several different New York newspapers all reporting on a comet giving different numbers of tails behind the astronomical body, two, three, four, or six depending upon the publication. The article also provided support for Thayer’s distrust of the press—or what he called, borrowing a term from Ezra Pound, the wypers. Later in the year, as Thayer was playing around the idea of a Fortean University—what he unsubtly codenamed F.U.—Sussman kicked in $25 toward the cause; the support—but not the amount—made issue 21. Two issues later, in December 1948, Sussman was credited among many, many other with contributing information on the story of Wonet, the Fortean cause célèbre, strongly suggesting that Sussman was paying close attention to Thayer and his Society.

Sussman appeared twice in 1949, both in issue 24 (April) on pages 364 and 365, displaying both his contempt for authority and a mordant humor (that may have bled into a belief in the occult). The first story he sent in concerned a new feed for hogs, cattle, and poultry that was showing promise. It was 50% molasses—and comically-treated sawdust. “End result, more cancer?,” Sussman asked. Other Forteans, particularly Thayer and Russell, were similarly concerned with the industrialization of the food supply. On the next page of the magazine was a story about Jake Bird. Thayer did not report Sussman’s comments—if any—so it is necessary to speculate. The article was about Jake Bird, who had been sentenced to die for murder, but predicted his enemies would be there at the pearly gates to greet him: and, indeed, before he was executed, a number of police, prosecutors, and court employees involved in his case had died. There’s a black humor inherent in the story—at the expense of authorities—and also the possibility of some occult powers, either the ability to see the future or some Wild Talent that allowed Bird to kill his accusers from afar. Sussman’s exact interest is unclear, and may have been in both aspects.

The ad man continued his connection with the Fortean Society into the 1950s, though his interest and understanding of Forteanism is impossible to track—whether it had evolved or not is unknown. Thayer’s references are just too vague. The only one of any substance is the first of the decade, in Doubt 29, July 1950. Thayer hosted a dinner for Garry Davis, to see if he would accept a Fellowship with the Fortean Society. (Thayer had earlier sent him a letter asking, and Thayer had responded that he wasn’t clear what Forteans were.) Among those at the dinner were Scott Nearing, J. M. Scandrett, the endocrinologist Harry Benjamin, actor Fred Keating, and Sussman. This very different meeting of the Fortean Society—echoing the one from almost 20 years before, but with an almost entirely different cast and intention—was also not meant for publicity: Thayer pointedly said that the press had not been invited.

Sussman’s name appeared four more times in Doubt, 36 (April 1952), 43 (February 1954), 45 (July 1954), and 52 (May 1956). These were generic credits, though, without Thayer correlating them to specific contributions, so it is impossible to say what Sussman contributed. Worth noting, though, is that he seemed to be drifting away, like so many other Forteans who were enthusiastic during the 1940s but did not continue through the decadal transition. Four contributions in four years is not many, and there’s not a single reference to Sussman in the final three years of the Society. The constellation of emotions and fears that motivated Sussman in the 1930s and, especially the 1940s—when he voluntarily came back to the Society, with no need to advertise Fort—had dissipated. Although Sussman would remain interested in esoteric literature at least into the 1960s, his Forteanism seems to have wavered, or, at least, was no longer on public display. I cannot find him making any reference to Fort after the 1950s, with he single exception of answering Damon Knight’s questions about Fort, Forteanism, and Thayer for Knight’s biography of Fort.