Though one would never know it from “Doubt” or the Fortean Society.

George Townsend Wetzel was born 1 June 1921 in Maryland. His name seems unusual, but there were a number of Wetzels, including other George Wetzels, throughout Maryland, Pennsylvania, and the upper Midwest. It’s a German name. His mother was the former Eva Mae Carrick. His father, Otto, was an accountant; he had served in the navy during the Boxer Rebellion. Both were born in the late 1880s; both were Marylanders, from families of Marylanders. George was the third of six children; he had an older brother and sister, and three younger brothers. In 1930, they rented a house for $37.50 in Baltimore. They did not have a radio set.

The family weathered the Depression well. They moved during the 1930s, into a home that they owned. According to the 1940 census, Otto was working full time in 1939, making about $3,500 per year. George was the eldest of the four boys still at home; I am not sure if he finished high school—the census credits him with one year, his enlistment papers with three. He subsequently seems to have done “semiskilled” machine work for a a couple of years at most. (The 1942 Hagerstown City Directory has a George Wetzel listed, working as a “greaser.”) On 6 June 1942, a few days after he turned 21, Wetzel enlisted in the army. From what I can tell, he served in the army air force, though I am not sure what he did beyond that. Wetzel was five-foot-nine and a slight 137 pounds.

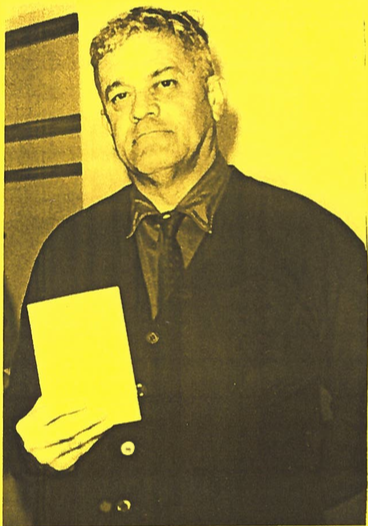

Wetzel, 1975.

Wetzel, 1975. As far as I can tell, this interest in the off-trail began with an enthusiasm for science fiction and fantastic literature, particularly the work of H. P. Lovecraft, who died in 1937, when Wetzel was in his mid-teens. I cannot say exactly when Wetzel started reading fantasy stories, but he became active in fandom during the late 1930s. In 1939, the author Frederic Arnold Klummer, Jr., started opening his Baltimore home for monthly meetings of the just-formed local chapter of the Science Fiction League. Wetzel was among the earliest members, if not one of the four charter members—he had just joined the Science Fiction League and would go on to name-drop his connection with Klummer.

Taking a page from Lovecraft’s history—Lovecraft had been an amateur journalist—as well as other science fiction fans who were publishing fan magazines—‘zines—Wetzel opted to start his own amateur publication; he announced his intention in the February 1941 issue of “Thrilling Wonder Stories.” “The Universal Hound, as his publication was to be called, would publish stories by amateur science fiction writers looking to break into the business. He hoped to generate interest by offering competitions, with original art from the science fiction magazines as prizes, and took Klummer on as an adviser. Wetzel may have also been writing fiction of his own, though I do not believe any of it survives from this early in his career, nor do I know if “The Universal Hound” ever saw the light of day.

Wetzel also contributed to other ‘zines. Harry Warner, the historian of science fiction fandom, notes that he sent a contribution which was printed in the fourth issue of Donn Brazier’s Fortean ‘zine “Frontier.” I have not seen the document; it would have been from early 1941. Warner reports, that Wetzel recounted the story of a shaft of purest light that amazed New Yorkers and extrapolated from this event a future in which we plug in lamps to darken a room. Warner wasn’t sure what to make of the contribution—was Wetzel being serious? Was this Fortean play or science fiction prediction along the lines of what John Campbell was advocating in “Astounding”?

Understandably, there is a gap in Wetzel’s fan activities that coincides with his wartime service. I find no mention of him in the amateur or professional magazines until 1946. That year, he contributed a number of items to another of Brazier’s ‘zines, Ember, issues that I have seen. He seems to have come out of the war reconstructed, less a writer—though he would still try to his hand at telling some weird tales—and more of a researcher. In Ember 6—dated 4 August 1946—he sent in some reports related to the Salem Witch Trials; in issue 18, dated 19 October 1946, he had some musings on “the emotional basis in the melodic line”; and in the undated issue 8, he noted that he was reading “Blavatsky’s “Isis Unveiled,” which he found “a gold mine of outré facts and assumptions,” commenting particularly on the reference to tunnels beneath the Pacific Ocean that connected disappeared islands.

Wetzel also appeared in a 1946 issue of Walter Dunkelberger’s FANews, number 275, otherwise undated. (Dunkelberger’s ‘zine was closely connected with Brazier.) Wetzel noted that he researches folklore and witchcraft—hence his earlier contribution about Salem—during the course of which he discovered a lost manuscript by Henry S. Whitehead. Whitehead was a writer of weird tales and friend of Lovecraft. I am not sure what manuscript he means. Wetzel also did seminal research on the writer Edward Lucas White, but this would be much later in Wetzel’s career—it was published only a few years before he died.

Wetzel is primarily known for his similarly seminal work on Lovecraft. He later wrote (in “A Memoir of Jack Grill), “In the late 1940s and the entire 1950s I was the only full-time active HPL scholar (though there were general one-shot articles by others).” I do not know the historiography of Lovecraft studies well enough to evaluate the claim, but he does seem to have been in select company, at the very least. According to a later newspaper report, Wetzel seems to have relied mostly on his military pension to support his technique of diligently searching through every issue of publications “hunting down unlisted writings by H.P. Lovecraft, the SF grand master; and patiently put[tin] together a Lovecraft bibliography.” In practice, this meant, especially, looking through The United Amateur Press Association journals for anonymous and pseudonymous works by Lovecraft (who, early in his career, used a variety of noms de plume).

Some of Wetzels’ writing from this period is known, though from later versions. In 1947, he wrote the first draft of what would become “A Jug of Whisky,” using Maryland folklore to see if it could be refined the way that Hawthorne refined New England lore. (Hawthorne had also been a major influence on Lovecraft.) The story eventually”—but never again, not even in Wildside’s recent “The Complete Weird Fiction of George T. Wetzel,” came out in his 1955 mimeographed collection “The Gothic Horror and Other Stories Like so many of his tales, “A Jug of Whisky,” lacked any sense of pacing, a novella’s worth of material being compressed into two pages. It told of a night at a saloon, when a stranger visited, trying to escape death, and got caught in a windmill; of a practical joke pulled on a drunk sailor; and of the town’s social organization. The conclusion had the sailor—named Carrick, Wetzel’s mother’s maiden name—digging up a jug of whisky from a grave, only to be scared off of it when a voice spoke from the bottle, and the skeletal remains of the dead man returned to claim it.

There were other story fragments and drafts making the rounds in the late 1940s, getting rejected, repurposed: a version of his lightweight “A Tale of the Elder Gods” was first published at this time, in a small ‘zine, but would not reach a wider audience until the late 1970s. “The Evil Earth”—also uncollected, except in the 1955 mimeographed pamphlet—may have been written about this time, too. It is about as long as “Jug,” but was much more atmospheric, with hardly any plot. It told of a cog in a political machine who went to a cemetery to get names for faking votes, met some boys playing there, and so, after sun down, the very place come alive, the earth move, vegetation burst forth. Wetzel said he based the story on a news report of a cemetery being considered for reconstruction as a playground, and his interview of some kids hanging around the place.

In addition, he was also writing about Lovecraft. August Derleth’s “Arkham Sampler” ran Wetzel’s “On the Cthulhu Mythos” in the spring of 1948. I have not seen the essay, but I think it is an early version of his “The Cthulhu Mythos: A Study,” which was published in 1955 and expanded in 1971. If so, then his argument was something along the lines of this—that the Cthulhu's Mythos was an integrated narrative arc, with various stories by Lovecraft contributing chapters to what was essentially a novel of earth’s alternative history. It tells of “supernormal” beings and their struggle to regain mastery over the world. Over the course of Lovecraft’s works, then, is slowly unfolded the description of a hellish dreamworld and the fate of ghoul changelings.

Into the early and mid-1950s, Wetzel continued all of this work, writing weird fiction, researching Lovecraft, investigating other aspects of fantastic literature, and putting out fan publications. His story “Anonymous,” was reportedly written in 1951; it’s a Lovecraft pastiche about a man in a dilapidated Maryland mansion reading an old book about drug-induced time travel. It was later published in the 1970s, and then the Wildside omnibus. He revised “Jug,” and it appeared in the ‘zine “Renaissance” in December 1952. “Evil Earth,” originally titled “Playground,” appeared in the Fall 1952 issue of the ‘zine “Fantasias.” He also contributed something to “Fanvariety” in that year, though I have not seen the issue to know what, exactly. “Fan-Fare” ran several humorous letters by him from 1951 to 1953, and he also appeared in the later columns of a few professional magazines.

It was during 1952 that he wrote perhaps his most effective story, “Caer Sidhi.” In the fall, he discovered Edgar Allen Poe’s fragment “The Lighthouse.” Inspired, he wrote an ending. At he time, Robert Bloch was supposedly engaged in a similar project, and Wetzel deferred to him, keeping the story under wraps (until 1954, when it ran in the ‘zine “Fanfare.” It would reappear in 1955, the 1962 anthology “Dark Mind, Dark Heart,” the late 1970s, and 2015). It was about two men isolated at a lighthouse who suffered storms and cosmic anomalies—the stars just didn’t seem right. The story also reflects the legend of Smalls Lighthouse: in the early 1800s, one of two feuding keepers there died, and the other lashed his body to the outside of the building, but winds kept it visible, slowly driving the man nearly mad.

At some point during this period, Wetzel made his way to Philadelphia and the Franklin Institute, which housed the Library of Amateur Journalism, looking for old, undocumented works by Lovecraft. He found an unknown poem, “Poetry and the Gods,” which he brought to the attention of Derleth. (There’s an undated letter from Wetzel to Derleth in private hands; given that Wetzel appeared in Derleth’s 1948 publication, it is likely that the letter comes from around that time, but it may be later.) In 1952, Wetzel started a new ‘zine “The Lovecraft Collector’s Library” in 1952. The ‘zine ran into the mid 1950s, the final volume, number 7, appearing in 1955, I believe. Wetzel reprinted “Poetry and the Gods” in the first issue. He admitted that the poem was amateurish, and thought only the middle third was worth consideration at all. Other essays through the years included “The Pseudonymous Lovecraft,” “Lovecraft’s Literary Executor,” and “Copyright Problems of the Lovecraft Estate.” {The entire run of the 'zine comprised some 250 pages; it was reissued in 1979.}

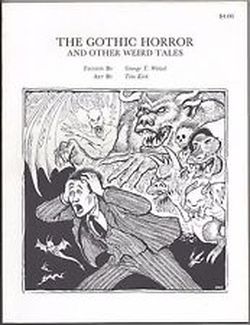

In addition to putting out his Lovecraft ‘zine, Wetzel was also contemplating theoretical issues related to gothic literature and its cognates. One of these was, in his words, “fruitless attempts to find anywhere an explanation for the grotesque in Gothic art.” Frustrated by the evidence, he turned to fiction, putting forth his own idea in the form of a story. In “The Gothic Horror,” he argued that pagan ritual was embodied in the stone architecture, cathedrals instantiating satanic ritual. The story climaxes with the narrator trapped in a room with one of the heathen creatures, driven to babbling. “The Gothic Horror” appeared in the ‘zine “Fanfare,” in May 1953, and then was collected as the title piece of his mimeographed book in 1955, before appearing in the reprinted collection in the late 1970s and then Wildside’s book.

During this period, Wetzels’ research widened. During the mid-1950s, he sent out his pamphlet “The Wizard of South Mountain,” about Michael Zittle, Sr., a German immigrant to Maryland who in the late 1700s wrote “The Friend on Need; or Secret Science,” which was a book of magical remedies, at least at Wetzel described it. The pamphlet told of his research, since around 1946, tracking down various editions of Zittle’s book, and Wetzel’s attempt to understand not only it but the response of other interpreters. Wetzels’ write up of what he called a “conjure book” ran to 14 typescript pages.”The Wizard of South Mountain” provided a suggestion for a story that became “The Saga of Mr. Cushwa, which itself was finally written in February 1955 and appeared in his mimeographed story collection; it has never been reprinted. The story was a collection of rumors about an eccentric villager and the seemingly odd—but perhaps not—events that befell those who became too nosy for their own good.

During this period, Wetzel was also spending an inordinate amount of time at the Enoch Pratt Free Library’s Maryland room and the Peabody Institute Library reading through 80 years of The Baltimore newspaper “The Sun,” looking for weird events to note. I don’t know all of the topics he covered, but am sure that whenever he came across reports of strange creatures living in water pipes or references to caves, tunnels and an underground world below Baltimore, or sea serpents, he put down the event in his notebooks, and then looked for confirmation in other newspapers. He compiled the numerous references to eels and worms and snakes appearing in Baltimore’s water supply into “Natural History in Water Pipes,” which he mimeographed and gave to friends. In December 1954 he put out its sequel, “Baltimore Subterranean.” For the latter, he tried to visit each site that he wrote about. His essay on sea serpents, “The Sea Serpent, Its Existence Proved by George Wetzel” appeared in the May 1955 issue of the ‘zine “Umbra,” put out by Baltimore silence fiction fans. The article similarly stitched together various news reports from Baltimore newspapers. (It is worth pointing out the Lovecraftian themes here: underground worlds and the horrors of ocean life.)

But Wetzel had not left behind gothic stories—that would remain an abiding interest. In 1955, he revised a story called “The Entity,” based on Fort’s “Wild Talents,” Fritz Leiber’s contention that the modern urban supernatural landscape would differ from the Gothic, and offering a different ending Poe’s “The Man of the Crowd.” It appeared in the 1955 version of “The Gothic Horror,” and the subsequent reprints through 2015. That same year, he wrote in introduction for Lovecraft’s “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath,” and published what was probably a revision of his 1948 essay, “The Cthulhu Mythos: A Study.” He also copyrighted a bibliography of Lovecraft’s writing based on his decade of research. Those were followed, a few years later, by “The Mechanistic-Supernatural of HPL” (1958) and “Notes on the Cthulhu Mythos” (1959). At the end of the decade, he visited Rhode Island, where he read through Lovecraft’s papers at Brown and went to sites he thought inspired some of Lovecraft’s tales, or were their settings.

In January 1957, Wetzel moved from his long time home at 5 Playfield Street, Dundalk, Maryland, to the Tollgate community in Owings Mill. I do not know much about his personal life from this period. He apparently did not have a car as of the late 1950s, but was close enough to extended family that they would offer rides to his friends; his father had recently died, in 1954. He had a girlfriend or fiancée—“a wife-to-be,” he called her at a much later date—as of the end of 1957. (He may have moved again, to Frederick, by 1960, or that may have been another George Wetzel.) I am not sure, and cannot confirm, but there is one report of him him marrying Arlene Florence MacDonald in 1963. He would have been in his early 40s, and she—if I’ve got this write—her late 40s. Wetzels’s mother died in 1969.

The marriage may account for Wetzel’s relative quiet during the 1960s. There also seems to have been a falling out with Lovecraft’s champion August Derleth—at least, one of Wetzel’s essays from the early 1970s snipes at Derleth quite a bit. {Actually, this last seems to have been the case. As Wetzel told the story, Derleth asked him to do a Lovecraft Bibliography for a 1958 publication--but then had Jack Chalker do it, instead, mostly copying everything that Wetzel had worked so hard to find and compile. Upset, Wetzel stopped publishing for more than a decade, but set himself the task of untangling the skein of confusion around the question of who owned the Lovecraft copyrights. This was a shot at Derleth, who claimed to control them; Wetzel showed that he actually had little basis for this contention. Another contributing factor to Wetzel's quiet after the mid-1950s was enmity between him and other fans. Wetzel was given to making disparaging remarks about Jews and blacks, which supposedly prompted one fan to sic postal inspectors on him. Wetzel withdrew from the fan community, irritated.}

{His temper had cooled slowly. He was drawn back to Lovecraft research in 1972, and fan activities in 1975. He started publishing again}, sometimes putting out new stuff, sometimes reworking older material. “The Shadow Game” appeared in the 1971 Arkham Collector. (This was the year that Derleth died.) It was never collected. There followed “What the Moon Brings” (1972); “Eater of the Dead” (1972); “Nightmare House” (1973); “Poison Pen” (1974); “The Adventure of Gosnell” (1977); “Jumbee” (1977); “Seeing Things at Night” (1978); “and “The Pirate of Shell Castle,” all of which were in Wildside’s 2015 omnibus. There was also the earlier collection “The Gothic Horror” in 1978 {and his Collector's Library}. He also continued publishing on Lovecraft: “Biographic Notes on Lovecraft” (1971); “A Memoir of Jack Grill” (1972); “A Lovecraft Profile” (1973); “Genesis of the Cthulhu Mythos” (1976).

{Supposedly, Wetzel lost his job around 1976; he reported that he was an ‘electronics worker,’ whatever that meant. He started doing janitorial work. Wetzel had quit smoking in the late 1960s—according to a friend—but still seems to have suffered from its ill-effects, developing a “hernia of the esophagus” and angina.}

George Wetzel died {9 or} 10 November 1983. Sixty-two years-old, he was buried at Providence United Methodist Church Cemetery.

George Wetzel died 10 November 1983. Sixty-two years-old, he was buried at Providence United Methodist Church Cemetery.

**************************

I do not know when George Wetzel discovered Fort—and it is clear that he discovered Fort himself, not just the Society. Born in 1921, he was among the youngest of Forteans in the immediate post-War years through to the Society’s end. Fort’s first book came out two years before he was born, and Wetzel was 11 when Fort’s last book came out, and the man himself died. Perhaps Wetzel recounts some of his Fortean history in one of his ‘zines—he published a few—but these are rare and expensive; I have not seen them, so, in the absence of anything more definitive, am forced to speculate. He entered organized fandom in the late 1930s, and so it is likely he came across Fort at this time, if not immediately then with the publication of the omnibus edition in 1941. If not then, he had to become aware of Fort when he was contributing to Donn Brazier’s and Walter Dunkelberger’s ‘zines, since both mentioned Fort, and Brazier’s “Frontier” was explicitly Fortean.

Whatever the origination of his Forteanism, Wetzel took Fort very seriously, and crafted himself into a Fortean researcher.

What, after all, was his going through eighty-years’s (!) worth of newspaper on microfilm, looking for anomalous reports, but a Fortean endeavor? And then he swung hem together in essays. These lacked the verve of Fort’s best work, the animating puckishness, but they had something so very often ignored by other Forteans: humor. Wetzel cast his natural history in the pipes as a battle between dipsomania and temperance: for what alternative did one have, except spirits, when the water pipes divulged winged eels? His subterranean world was a place of mystery, and was also narrated with a light touch. Only his work on sea serpents was not quite more than a string of references; perhaps that is why it appeared in a ‘zine, but got no wider distribution. Wetzel suffered the same slings and arrow as Fort, dismissed, he said, because he only had a high school education, the way some dismissed Fort for being an amateur in the garden of science. (This lack of respect may have further predisposed Wetzel tot he Fortean Society, what with its blast at the American educational system.)

Wetzel told a newspaper writer in 1955, that he spent so much time going through newspapers in the hopes of finding good story ideas; he was like so many writers of fantastic literature, though, who took Fort’s anomalies and spun them into weird tales and science fiction stories. And, indeed, as he himself admitted, Wetzel was willing to take Fortean data as the basis of his fiction. “The Entity” was about a strange tramp who catches the eye of the narrator. In the course of following the mysterious person, the storyteller sees him reading a newspaper story—a report, it turns out, ripped from the pages of “Wild Talents,” about a man found dead on a park bench. Fort speculated that this man had a warning that sitting upon a particular park bench would mean his death; he avoided it, and someone took his place—both on the bench and in death, sucked dry by some thing. But then, two days later, the man sat on another, nearby bench and was cut down.

“The trail of the intended victim was picked up—” is how Fort put it, with the dash at the end. And this is where Wetzel takes up the issue, Fort supplying the ending Wetzel wanted for Poe’s “The Man in the Crowd.” The tramp was driven by a hunter. And now that the narrator had sussed out the strange workings of the urban supernatural, he was the next victim. He would be hounded until death finally caught him unawares.

By the time Wetzel wrote “The Entity,” he had joined the Fortean Society, but he would not contribute much to it—or, better put, not much that was mentioned in Doubt. Part of the issue was probably that he was busy enough with his own writing and research he had no reason to fill Thayer’s magazine; part was probably that his interest was primarily Lovecraft—though Wetzel saw a tight correspondence between Lovecraft and Fort, one tighter than even Lovecraft acknowledge. The rest of the reason seems to be that Thayer did not promote Wetzel as he could have. I cannot say why this is, exactly. There are some mentions of Wetzel being argumentative, but I have seen no evidence of a confrontational nature. It may just be that by the mid-1950s, Thayer was tiring of the Fortean Society, as he told Eric Frank Russell, as well as science fiction and its associated genres.

At any rate, Wetzel appeared in Doubt just twice. The first time was issue 45 (July 1954). It was a generic acknowledgment at the end of the issue, so it is impossible to know what—or even how may data—Wetzel contributed. The final mention came the following year, in Doubt 48 (April 1945). Thayer waxed rhapsodic about Wetzel’s “Natural History in the Water Pipes”: Wetzel had apparently sent him several to distribute:

“MFS George Wetzel has written and produced an 18 karat Fortean item of which only 70 copies exist. It is Natural History in the Water Pipes, and concerns itself with the eels and fish and other critters which have frequently been drunk by humans in tap water. What’s more, the material is handled in a manner reminiscent of Fort himself. YS got three solid laughs out of its 8 mimeographed pages, fully documented. It’s a home-made job, put together with wire staples, rather too full of typographical errors and so on, but one feels sure you will treasure it, all the same. Suppose you send 80 cents. Money back on request.”

Wetzel seems to have sent Thayer other materials, which (I think) the Fortean Society Secretary filed with other ‘zines and science fiction ephemera. This supposition is based on some material I bought from James Cummins, Bookseller, labelled “Wetzel/Thayer fanzines.” It comprised the copy of “Umbra” with the sea serpent article, addressed to Wetzel; a copy of the ‘zine “Eusifanso,” from 1950, addressed to Thayer and having nothing to do with Wetzel; “The Wizard of South Mountain,” addressed to Thayer from Wetzel; a copy of the 1955 “Gothic Horror and Other Stories,” also from Wetzel to Thayer; and a copy of the ‘zine “Triton” addressed to Thayer from the publishers, again having nothing to do with Wetzel. To repeat: I do not know why Thayer called no attention to Wetzel’s other writings, but having it filed with the ‘zines does suggest that he considered it a kind of science fiction, which may account for his dismissal.

The brief contact between Wetzel and the Society underplays the extent to which Fort influenced his thought; even his own Fortean works—fiction and non—underplays it. Wetzel saw in Fort a kind of materialistic enchantment that characterized his own thought—and, he opined, Lovecraft’s, too, though Lovecraft tried to put some distance between himself and Fort. Wetzel, though intrigued by weird tales, could not bring himself to believe in magic. (He said so in his manuscript on Zittle.) But the world was obviously full of weird things—he’d documented them himself, eels and fish in water pipes, unusual tunnels, phenomena that could inspire awe and fear. Could one have the weird without the supernatural?

Wetzel thought so. He had an extended riff on Fort and Lovecraft in his 1958 essay “The Mechanistic Supernatural of Lovecraft.” (It originally appeared in “Fresco,” a Lovecraft ‘zine out of Detroit.) He wrote,

“It was inevitable that with his interest in the supernatural . . . and his mechanistic philosophy . . . that [Lovecraft] tended in his *fiction* to treat supernatural phenomena in which he did not believe as due to a part of a mechanistic nature still little understood by science but, just the same, explainable since it did presumably have existence. It is this view of a ‘mechanistic-supernatural’ that lends a curious air of realism to his most extravagant supernatural conceptions and which has striking parallels to the controversial philosophy of Charles Fort . . .

“Lovecraft subscribed to the mechanistic theories of Democritus as early at least as 1920, that nature lacks a purpose. It was at about this same time that a mechanistic supernaturality was vaguely beginning in his fiction. Fort’s ‘Book of the Damned’ was printed in 1919 and may have been an influence than on HPL but there exists no proof of this. However as HPL was later to show a direct influence from Fort, he may have read ‘The Book of the Damned’ sometime before 1926, and it could have given additional direction and clarification to HPL’s idea that the supernatural (considered fiction-wise) was not the product of superstitious minds but was explainable by mechanism.

“The influence of Fort is obvious in HPL’s story ‘The Call of Cthulhu’ (1926) in which Fort is named. The plot os that story (just as in Fort’s controversial collations in his books) depends on dissimilar but simultaneous phenomena being explained as the results of a common cause. This Fortean ‘plot’ is discernible in a second prose experiment of HPL’s: he wrote ‘The Dunwich Horror’ (1928) and followed it with ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’ (1930), giving both stories a provokingly similar internal chronology, so that suspicion exists that the two separate supernatural situations had something in common, some single cause. In addition ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’ has an idea right out of Fort’s ‘Book of the Damned,’ chapter 10, that extraterrestrial creatures have walked this earth disguised in human masks.”

Without denying the parallel Wetzel notes between Lovecraft and Fort—without even denying that Wetzel may be exactly right—and without getting into an investigation of the exact relationship between Fort and Lovecraft, it is worth noting that Lovecraft himself was sometimes troubled by Fort. In a 1927 letter to Donald Wandrei, for example, he dismissed some of Fort’s hypotheses as “glib.” The point here is not what Lovecraft thought of Fort, or even what he did with Fort, but how Wetzel thought of the two writers. It is hard not to conclude that Wetzel imagined Lovecraft finding in Fort exactly what Wetzel himself found: a key to understanding the world, a way of experiencing the world as weird and wonderful—enchanted—without giving in to the temptation of supernatural belief.

Fort was just the kind of Fortean that Wetzel wanted to be.

Perhaps that is the real reason he stopped contributing to the Fortean Society. There was little to none of Fort’s mechanistic explanation of the anomalous in “Doubt.” Thayer was not the right kind of Fortean.